Ocean-To-Ocean Highway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Us 17 Corridor Study, Brunswick County Phase Iii (Functional Designs)

US 17 CORRIDOR STUDY, BRUNSWICK COUNTY PHASE III (FUNCTIONAL DESIGNS) FINAL REPORT R-4732 Prepared For: North Carolina Department of Transportation Prepared By: PBS&J 1616 East Millbrook Road, Suite 310 Raleigh, NC 27609 October 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION / BACKGROUND..............................................1-1 1.1 US 17 as a Strategic Highway Corridor...........................................................1-1 1.2 Study Objectives..............................................................................................1-2 1.3 Study Process...................................................................................................1-3 2 EXISTING CONDITIONS ................................................................2-6 2.1 Turning Movement Volumes...........................................................................2-7 2.2 Capacity Analysis............................................................................................2-7 3 NO-BUILD CONDITIONS..............................................................3-19 3.1 Turning Movement Volumes.........................................................................3-19 3.2 Capacity Analysis..........................................................................................3-19 4 DEFINITION OF ALTERNATIVES .............................................4-30 4.1 Intersection Improvements Alternative..........................................................4-31 4.2 Superstreet Alternative...................................................................................4-44 -

F-4-100 Braddock Monument

F-4-100 Braddock Monument Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 01-31-2013 MARYLAND HISTORICAL TRUST NR Eligible: yes DETERMINATION OF ELIGIBILITY FORM no kopertyName: Braddock Monument Inventory Number: F-4-100 Address: South side ofU.S. 40 Alternate Historic district: yes X no City: Braddock Heights, MD Zip Code: County: Frederick USGS Quadrangle(s): Frederick Property Owner: Daughters of the American Revolution, Frederick Chapter Tax Account ID Number: Tax Map Parcel Number(s): Tax Map Number: Project: Monument relocation Agency: MD SHA Agency Prepared By: MD SHA Preparer's Name: Anne E. Bruder, Architectural Historian Date Prepared: 04/07/2009 Documentation is presented in: Project Review and Compliance files. -

Unincorporated Communities Cemeteries

Brunswick County, North Carolina Final Report t epartmen D opment l Communities Communities 2010 by: eve D ty i Prepared September CemeteriesCemeteries ommun C & ng i Geographic Information Systems Department ann Unincorporated Unincorporated PlPl i & C i D l D Table of Contents BRUNSWICK COUNTY UNINCORPORATED COMMUNITIES & CEMETERIES INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 2-1 UNINCORPORATED COMMUNITIES WITH MAP ANTIOCH .................................................................................................................................... 2-8 ASH, PINE LEVEL, and SMITH ................................................................................................. 2-9 BATARORA .............................................................................................................................. 2-10 BELL SWAMP ........................................................................................................................... 2-11 BISHOP ...................................................................................................................................... 2-12 BIVEN* ...................................................................................................................................... 2-13 BOLIVIA .................................................................................................................................... 2-14 BONAPARTE LANDING* ...................................................................................................... -

Salisbury/Wicomico Area Long-Range Transportation Plan

Salisbury/Wicomico Area Long-Range Transportation Plan final report prepared for Salisbury/Wicomico Area Metropolitan Planning Organization Maryland Department of Transportation October 20, 2006 Salisbury/Wicomico Area Long-Range Transportation Plan Salisbury/Wicomico Area Metropolitan Planning Organization Board Members Marvin R. Long, Wicomico County, MPO Chair Rick Pollitt, City of Fruitland, MPO Vice Chair Michael P. Dunn, City of Salisbury Charles Fisher, Tri-County Council for the Lower Eastern Shore of Maryland Luther Hitchens, Town of Delmar, Maryland Mike Nixon, Maryland Department Of Transportation John F. Outten, Town of Delmar, Delaware (Non-Voting) Stevie Prettyman, Wicomico County Ralph Reeb, Delaware Department of Transportation (Non-Voting) Theodore E. Shea II, Wicomico County Barrie P. Tilghman, City of Salisbury Technical Advisory Committee John Redden, Wicomico County Department of Public Works, Chair Ray Birch, City of Salisbury Public Works, Vice Chair Dr. Kwame Arhin, Federal Highway Administration Brad Bellaccico, City of Salisbury Chamber of Commerce, Transportation Subcommittee Bob Bryant, Ocean City/Wicomico County Airport Authority Salisbury/Wicomico Area Metropolitan Planning Organization Salisbury/Wicomico Area Long-Range Transportation Plan Bob Cook, Delmarva Water Transport Advisory Committee, (Ex-Officio) James Dooley, State Highway Administration Tracey Gordy, Maryland Department of Planning Rob Hart, Shore Transit Lenny Howard, Maryland Transit Administration Dan Johnson, Federal Highway Administration -

Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised)

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NPS Approved – April 3, 2013 National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items New Submission X Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised) B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) I. The Santa Fe Trail II. Individual States and the Santa Fe Trail A. International Trade on the Mexican Road, 1821-1846 A. The Santa Fe Trail in Missouri B. The Mexican-American War and the Santa Fe Trail, 1846-1848 B. The Santa Fe Trail in Kansas C. Expanding National Trade on the Santa Fe Trail, 1848-1861 C. The Santa Fe Trail in Oklahoma D. The Effects of the Civil War on the Santa Fe Trail, 1861-1865 D. The Santa Fe Trail in Colorado E. The Santa Fe Trail and the Railroad, 1865-1880 E. The Santa Fe Trail in New Mexico F. Commemoration and Reuse of the Santa Fe Trail, 1880-1987 C. Form Prepared by name/title KSHS Staff, amended submission; URBANA Group, original submission organization Kansas State Historical Society date Spring 2012 street & number 6425 SW 6th Ave. -

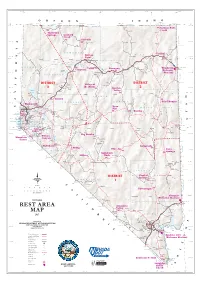

Rest Area Map 2017.Ai

250 000 mE 300 000 mE 350 000 mE 400 000 mE 450 000 mE 500 000 mE 550 000 mE 600 000 mE 650 000 mE 700 000 mE 750 000 mE 120° 119º 118° 117° 116° 115° 114° OREGON IDAHO TO TWIN FALLS TO FIELDS TO JORDAN VALLEY TO MOUNTAIN HOME 42° LAKE TO ADEL TWIN FALLS CASSIA 42° HARNEY MALHEUR OWYHEE 4 650 000 mN Jackpot 4 650 000 mN Denio 292 140 McDermitt Owyhee Denio Jct 93 Salmon Falls 95 225 Mountain City Creek Contact Thousand 140 Springs Leonard Creek 293 MODOC Orovada 4 600 000 mN Orovada 4 600 000 mN Paradise Valley Jack Creek North Fork Wilkins ELDER BOX (site) 226 TO PARK VALLEY 140 290 Montello ION HUMBOLDT UN PACIFIC TO CEDARVILLE Pequop 233 Button ELKO Dinner Station 4 550 000 mN Deeth Wells 4 550 000 mN 231 95 Point 41° 230 41° Oasis 225 ALT Winnemucca 93 789 UNION UNION Jungo Halleck (site) Leeville PACIFIC Golconda 229 UNIO UNION (site) 294 N PACIFIC 80 80 Tungsten PACIFIC Elko Arthur WASHOE (site) Valmy 766 TO SALT LAKE CITY PACIFIC Spring 95 Valmy Creek Wendover West Beowawe Wendover 80 227 Lamoille Cosgrave 806 Gerlach Rye Patch Imlay Carlin Reservoir (Welcome Mill City 228 229 4 500 000 mN 4 500 000 mN Battle Mountain Empire 767 Station) PACIFIC 400 ALT (site) Copper Beowawe 93 Canyon PERSHING (site) 305 NORTHERN ON I 447 Unionville 306 UN 401 93 TOOELE Crescent 278 Jiggs Valley LASSEN Oreana Tenabo DISTRICT (site) DISTRICT NEVADA TO IBAPAH Currie U P Rochester Valley of 399 398 (site) Gold Acres (site) 4 450 000 mN 2 the Moon 3 4 450 000 mN Lovelock Garden Pyramid 397 Valley Lages Station 40 Lake 40° 445 NORTHERN Sutcliffe Cherry -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................. 1 Document Organization .............................................................................................. 1 Project Process .......................................................................................................... 3 Stakeholder Coordination ............................................................................................... 4 Vision, Goals, and Objectives .......................................................................................... 5 Existing Conditions ........................................................................................................ 7 System Overview ....................................................................................................... 7 City of Tallahassee ..................................................................................................... 9 ITS Infrastructure .................................................................................................... 9 Communications ..................................................................................................... 9 Traffic Management Center .................................................................................... 16 Traffic Signals........................................................................................................ 17 Bicycle Technology............................................................................................... -

Madonna of the Trail Lexington, Missouri the Statue Is a Tribute to the Many Hundreds of Thousands of Women Who Took Part In

Madonna of the Trail Lexington, Missouri The statue is a tribute to the many hundreds of thousands of women who took part in the Western United States Migration. Madonna of the Trail is a series of 12 identical monuments dedicated to the sprit of pioneer women in the United States. In the late 1920’s, the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (NSDAR) commissioned the design, casting and placement of twelve memorials commemorating the spirit of pioneer women. These monuments were installed in each of 12 states along the National Old Trails Road, which extended from Cumberland, Maryland, to Upland, California. The Madonna of the Trail is depicted as a courageous pioneer woman, clasping her baby with her left arm while clutching her rifle in her right, wearing a long dress and bonnet. Her young son clings to her skirts. On Monday, September 17, 1928, The Missouri Madonna of the Trail in Lexington, Missouri, was unveiled and dedicated. Harry S. Truman, a Missouri Justice of the Peace and the President of the National Old Trails Association, was the keynote speaker at the ceremony. The ceremony was in many ways a “home-coming” for Lexington, and the streets were crowded with visitors while homes were filled with guests. Most of the visitors were former residents, relatives, and people with connections with Lexington. Many people dressed in period costume, including some eighty-plus year old “real pioneer women” who were dressed in costumes that were over 100 years old. On August 25, 1928, prior to the dedication, a copper box time capsule, filled with pictures, books, pamphlets and other miscellaneous items, was deposited in the base of the pioneer mother statue. -

The Smart Club

There’s An Office Near You! 1.888.SHARP.40 The Sharp Open Mon - Fri, 8 am – 4:30 pm (1.888.742.7740) Energy Dover, Delaware 5011 N. DuPont Highway, Dover, DE Salisbury, Maryland Smart 520 Commerce St, Salisbury, MD Georgetown, Delaware Club... 22033 DuPont Blvd, Georgetown, DE Ocean View, Delaware 102 Central Avenue, Ocean View, DE Easton, Maryland Our 9387 Ocean Gateway, Easton, MD Pocomoke City, Maryland Commitment 648 Ocean Highway, Pocomoke City, MD To NEW Chincoteague, Virginia 4098 Main St, Chincoteague, VA Customers! Belle Haven, Virginia 36292 Lankford Hwy, #11, Belle Haven, VA “There before you need us” Allentown, Pennsylvania It’s easy to start saving 7205 Kernsville Rd, Orefield, PA Poconos, Pennsylvania with the Sharp Energy 106 Joe-Kern Rd, Blakeslee, PA Honey Brook, Pennsylvania Smart Club... Just 80 Village Square, Honey Brook, PA The Cecil County, Maryland contact your local Perryville, MD Smart Club office to sign-up. Smart Club benefits begin immediately. “There before you need us” 1.888.SHARP.40 (1.888.742.7740) 1.888.SHARP.40 (1.888.742.7740) Our Commitment to You... SE072012 www.sharpenergy.com Smart Save Smart with Regular Annual Total Club Customer Savings Savings Sharp Energy’s Customer Welcome to the Smart Club FIRST FILL Gallons ______ ______ Sharp Energy As a new Sharp Energy customer, you are @ 80% invited to participate in an exclusive, one-of-a- Cost per $______ $______ Smart Club... kind invitation. Introducing the Sharp Energy Gallon Has your propane usage been too low to take Smart Club. The Smart Club is for smart, new Fuel Cost $______ $______ full advantage of Sharp Energy’s Pro Cap Price customers like you who appreciate the advantages that come with great customer Protection Plan? Now there is a program that Annual allows you to cut your propane costs, too. -

Louisiana Emergency Evacuation

49E LMOiller ULafayette ISIColuAmbia NA EUnion MERGAshley ENChiCcot YWashington EVACUATION WMinston AP Holmes Attala Noxubee 371 Humphreys Cass 71 79 51 425 165 65 2 Morehouse Sharkey Yazoo Neshoba Kemper 3 Claiborne West Carroll Leake 2 Issaquena 55 167 Union 2 2 79 East Carroll Bossier 63 1 133 49 Madison Lincoln Monroe 17 65 Caddo 80 61 20 Harrison 220 Webster 80 167 Meridian Ouachita 80 Lauderdale Shreveport Jackson Newton 20 371 80 Scott 20 165 Richland 79 6 220 147 Madison Warren Jackson 20 80 Bienville 2 1 Hinds Rankin 71 17 Vicksburg 167 34 65 Panola 171 Franklin Caldwell Clarke Jasper 84 Red River Smith De Soto 165 Tensas 15 Claiborne 84 45 Winn Simpson 49 171 11 84 Copiah 49 1 84 Shelby Jefferson 55 84 Natchitoches Catahoula 65 Wayne 167 84 Covington Jones 6 71 La Salle 51 Lawrence 165 84 65 Natchez Jefferson Davis Sabine Lincoln 84 1 84 Concordia Adams 6 Franklin 28 59 Grant 61 San Augustine Mississippi Sabine Hattiesburg 171 Alexandria Greene Marion Lamar Forrest Perry 28 5 Pike 98 Wilkinson Amite Walthall Rapides Vernon 3 98 55 8 Avoyelles Texas 7 1 61 West Feliciana George East Feliciana 59 167 4 43 Washington 21 67 St. Helena Stone 71 25 19 Pearl River Newton 8 449 51 190 Evangeline 49 Pointe Coupee Jasper 27 165 49 East Baton Rouge 16 Tangipahoa 11 26 61 171 113 167 Tyler Beauregard Allen 13 16 Jackson 190 21 190 Harrison Tyler 110 109 190 190 St. Landry 41 12 190 West Baton Rouge 12 59 Hancock St. -

ORN Road Net Element

Unclassified Land Information Ontario Data Description ORN Road Net Element Disclaimer This technical documentation has been prepared by the Ministry of Natural Resources (the “Ministry”), representing Her Majesty the Queen in right of Ontario. Although every effort has been made to verify the information, this document is presented as is, and the Ministry makes no guarantees, representations or warranties with respect to the information contained within this document, either express or implied, arising by law or otherwise, including but not limited to, effectiveness, completeness, accuracy, or fitness for purpose. The Ministry is not liable or responsible for any loss or harm of any kind arising from use of this information. For an accessible version of this document, please contact Land Information Ontario at (705) 755 1878 or [email protected] ©Queens Printer for Ontario, 2019 LIO Class Description ORN Road Net Element Class Short Name: ORNELEM Version Number: 2 Class Description: The basic centreline road network features, which forms the spatial framework for the ORN. Road net elements are bound by a junction on each end, except for cul-de-sacs (loops) where there is only one junction. The ORN is segmented at real-world intersections (junctions) on the ground. Abstract Class Name: SPSLINEM Abstract Class Description: Spatial Single-Line With Measures: An object is represented by ONE and ONLY ONE line. All vertices along the arc have measures (values for x, y, m). Measures are required for dynamic segmentation/linear referencing. Example: Ontario Road Network road segments. Metadata URL: Tables in LIO Class: ORN Road Net Element ORN_ROAD_NET_ELEMENT_FT The basic centreline of road network features, which forms the spatial network of roads, composed of three types of road net elements, road element, ferry connection and virtual road. -

Swutc/09/476660-00003-2 Compendium of Student

Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. SWUTC/09/476660-00003-2 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date COMPENDIUM OF STUDENT PAPERS: 2009 October 2009 UNDERGRADUATE TRANSPORTATION SCHOLARS 6. Performing Organization Code PROGRAM 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Christopher Senesi, Stephanie Everett, Jordan Easterling and George Report 476660-00003-2 Bogonko, Authors, and H. Gene Hawkins, Editor 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Texas Transportation Institute Texas A&M University System 11. Contract or Grant No. College Station, Texas 77843-3135 DTRT07-G-0006 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Southwest Region University Transportation Center Texas Transportation Institute Texas A&M University System 14. Sponsoring Agency Code College Station, Texas 77843-3135 15. Supplementary Notes Program Director: H. Gene Hawkins, Ph.D., P.E. Participating Students: Christopher Senesi, Stephanie Everett, Jordan Easterling and George Bogonko. Supported by a grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation, University Transportation Centers Program. 16. Abstract This report is a compilation of research papers written by students participating in the 2009 Undergraduate Transportation Scholars Program. The ten-week summer program, now in its nineteenth year, provides undergraduate students in Civil Engineering the opportunity to learn about transportation engineering through participating in sponsored transportation research projects. The program design allows students to interact directly with a Texas A&M University faculty member or Texas Transportation Institute researcher in developing a research proposal, conducting valid research, and documenting the research results through oral presentations and research papers.