Bedford County

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine

Early Development of Transportation 115 EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF TRANSPORTATION ON THE MONONGAHELA RIVER By W. Espy Albig* Although the traffic on the Monongahela River from Brownsville to the Ohio had advanced from the canoe of the Indian and the Kentucky boat of the emigrant of Revolu- tionary times, to a water borne traffic of no mean size in passengers and miscellaneous freight, and to more than a million bushels of coal annually before the Monongahela waterway was improved by the installation of locks and dams late in 1841, yet no records remain of the constantly increasing stream of commerce passing over this route be- tween the east and the west. Here and there remains a fragment from a traveller, a ship builder or a merchant giv- ing a glimpse of the river activity of the later years of the 18th century and the early ones of the 19th century. The Ohio Company early recognized the importance of this waterway, and in 1754 Captain Trent on his way to the forks of the Ohio by Nemacolin's and the Redstone trails, built "The Hangard" at the mouth of Redstone Creek. From April 17th, when he surrendered his works to the French and retreated in canoes up the Monongahela, this avenue became more and more important until the steam railways supplanted the slower traffic by water. The easy navigation of this stream led that man of keen insight, George Washington, into error, when, under date of May 27, 1754, he writes: "This morning Mr. Gist ar- rived from his place, where a detachment of fifty men (French) was seen yesterday. -

The Principal Indian Towns of Western Pennsylvania C

The Principal Indian Towns of Western Pennsylvania C. Hale Sipe One cannot travel far in Western Pennsylvania with- out passing the sites of Indian towns, Delaware, Shawnee and Seneca mostly, or being reminded of the Pennsylvania Indians by the beautiful names they gave to the mountains, streams and valleys where they roamed. In a future paper the writer will set forth the meaning of the names which the Indians gave to the mountains, valleys and streams of Western Pennsylvania; but the present paper is con- fined to a brief description of the principal Indian towns in the western part of the state. The writer has arranged these Indian towns in alphabetical order, as follows: Allaquippa's Town* This town, named for the Seneca, Queen Allaquippa, stood at the mouth of Chartier's Creek, where McKees Rocks now stands. In the Pennsylvania, Colonial Records, this stream is sometimes called "Allaquippa's River". The name "Allaquippa" means, as nearly as can be determined, "a hat", being likely a corruption of "alloquepi". This In- dian "Queen", who was visited by such noted characters as Conrad Weiser, Celoron and George Washington, had var- ious residences in the vicinity of the "Forks of the Ohio". In fact, there is good reason for thinking that at one time she lived right at the "Forks". When Washington met her while returning from his mission to the French, she was living where McKeesport now stands, having moved up from the Ohio to get farther away from the French. After Washington's surrender at Fort Necessity, July 4th, 1754, she and the other Indian inhabitants of the Ohio Val- ley friendly to the English, were taken to Aughwick, now Shirleysburg, where they were fed by the Colonial Author- ities of Pennsylvania. -

William A. Hunter Collection ,1936-1985 Book Reviews, 1955-1980

WILLIAM A. HUNTER COLLECTION ,1936-1985 BOOK REVIEWS, 1955-1980 Subject Folder Carton "The Susquehanna By Carl Cramerl',Pennsylvania Magazine 1 1 -of History and Biography, Vol. LXXIX No.3, July 1955. &@$a-is "American Indian and White Relations --to 1830...11 By 1 William N. Fenton, et. al., Pennsylvania Magazine -of History -& Biography LXXXI, No.4, Oct. 1957. "Tecumseh, Vision of Glory by Glenn Tucker, "Ethnohistory 1 Vol. 4, No.1, winter, 1957. "Colonists from Scotland... by I.C.C.Graham,ll The New 1 York Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. XLI, ~c47 Oct., 1957. "Banners --in the Wilderness.. .. by H. T.W.Coleman," Pennsylvania History Vol.XXIV, No. 1: January 1957. "War Comes to Quaker Pennsylvania by Robert L.D. Davidson," 1 Pennsylvania~a~azine-of History and Biography, Vol.LXXI1, No.3, July 1958. "Indian Villages --of the Illinois Country.Historic Tribes By Wayne C. Temple."American Antiquity. Vol. XXIV No. 4: April 1, 1959. "Braddock's Defeat by Charles Hamilton." Pennsylvania History Vol. XXVII, No. 3: July, 1960. "American Indians, by William T. Hogan." Pennsylvania 1 Magazine -of History and Biography, Vol. LXXXV, No. 4:0ct.1961. "The Scotch-Irish: A Social History, by James G. Pennsylvania ~istory,Vol.XXX, No.2, April 1963. -----"Indians of the Woodlands ....By George E. Hyde" Pennsylvania 1 Magazine of History and Biography LXXXVII, NO.~: July, 1963. "George ----Mercer of the Ohio Company, By Alfred P. James", 1 Pennsylvania -History Vol. XXX, No. 4, October 1964. "The Colonial --Wars, 1689-1762, by Howard H. Peckham" 1 Pennsylvania Magazine -of Historx and Biography, LXXXVIII, No. -

13, Riverside View, Milton Ernest Bedfordshire MK44 1SG

13, Riverside View, Milton Ernest Bedfordshire MK44 1SG A very well presented five bedroom detached house nicely positioned within this very desirable development in the popular north Bedfordshire village of Milton Ernest. The spacious and well planned accommodation includes the light and welcoming reception hall, a sitting room with double doors opening to the separate dining room, a quality refitted kitchen/breakfast room with a range of integrated appliances, a utility room and a refitted cloakroom. On the first floor the large landing leads to the impressive main bedroom suite with en suite and large walk-in wardrobe and three further double bedrooms, a single bedroom and the refitted family shower room. Outside, there is a very attractive, professionally landscaped rear garden which is 57' wide x 40' deep, south facing with a shaped lawn, a paved terrace and with well stocked and colourful borders. To the front there is a block paved driveway providing parking for four cars, an integral double width garage and a well maintained garden. * 5 Bedrooms * Refitted cloakroom * 2 Reception rooms * Refitted kitchen/breakfast room * Impressive main bedroom suite * UPVC double glazing * Landscaped south facing garden * Sought after village location FREEHOLD “Hassett House”, Hassett Street, Bedford MK40 1HA www.taylorbrightwell.co.uk [email protected] 01234 326444 Money Laundering Regulations: Intending purchasers will be asked to produce identification documentation and we would ask for co-operation in order that there is no delay in agreeing a sale. Agents Notes: The agent has not tested any apparatus, equipment, fixtures & fittings or services and so cannot verify that they are in working order or fit for the purpose. -

POINT PLEASANT 1774 Prelude to the American Revolution

POINT PLEASANT 1774 Prelude to the American Revolution JOHN F WINKLER ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CAMPAIGN 273 POINT PLEASANT 1774 Prelude to the American Revolution JOHN F WINKLER ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS Series editor Marcus Cowper © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 The strategic situation The Appalachian frontier The Ohio Indians Lord Dunmore’s Virginia CHRONOLOGY 17 OPPOSING COMMANDERS 20 Virginia commanders Indian commanders OPPOSING ARMIES 25 Virginian forces Indian forces Orders of battle OPPOSING PLANS 34 Virginian plans Indian plans THE CAMPAIGN AND BATTLE 38 From Baker’s trading post to Wakatomica From Wakatomica to Point Pleasant The battle of Point Pleasant From Point Pleasant to Fort Gower THE AFTERMATH 89 THE BATTLEFIELD TODAY 93 FURTHER READING 94 INDEX 95 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com 4 British North America in1774 British North NEWFOUNDLAND Lake Superior Quebec QUEBEC ISLAND OF NOVA ST JOHN SCOTIA Montreal Fort Michilimackinac Lake St Lawrence River MASSACHUSETTS Huron Lake Lake Ontario NEW Michigan Fort Niagara HAMPSHIRE Fort Detroit Lake Erie NEW YORK Boston MASSACHUSETTS RHODE ISLAND PENNSYLVANIA New York CONNECTICUT Philadelphia Pittsburgh NEW JERSEY MARYLAND Point Pleasant DELAWARE N St Louis Ohio River VANDALIA KENTUCKY Williamsburg LOUISIANA VIRGINIA ATLANTIC OCEAN NORTH CAROLINA Forts Cities and towns SOUTH Mississippi River CAROLINA Battlefields GEORGIA Political boundary Proposed or disputed area boundary -

Character Assessment

Milton Ernest Character Assessment January 2017 TROY PLANNING + DESIGN Milton Ernest - Character Assessment (THP174) TROY PLANNING + DESIGN www.troyplanning.com Office: 0207 0961 329 Mobile: 07964149559 Address: 3 Waterhouse Square, 138 Holborn, London, EC1N 2SW P 2/59 January 2017 TROY PLANNING + DESIGN Milton Ernest - Character Assessment (THP174) Contents 1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 4 2 HISTORIC DEVELOPMENT .............................................................................. 7 3 THE APPROACH IN THIS CHARACTER ASSESSMENT .................................. 15 4 CHARACTER AREAS ....................................................................................... 19 5 HISTORIC MEDIAN ........................................................................................ 23 6 HISTORIC EASTERN ....................................................................................... 26 7 PRE-60S .......................................................................................................... 30 8 70S-80S .......................................................................................................... 33 9 80S-90S .......................................................................................................... 37 10 VILLAGE EDGE ............................................................................................... 40 ANNEX 1 - LOCAL MATERIALS ..................................................................... 43 -

For Lease Retail/Office Space 590 National Road, Wheeling, WV 26003

For Lease Retail/Office Space 590 National Road, Wheeling, WV 26003 Property Information � 15,000 SF of retail/office space available | Can be subdivided to 7,000 SF � Former corporate headquarters with custom finished board room and multiple executive offices � Potential build-to-suit - 8,000 SF of office/retail space � Local loan/incentive packages available for relocations � Well maintained commercial space � Elevator served � Signage opportunity on National Road � Over 50 on-site parking spaces � Located in the heart of the Marcellus and Utica Gas Shale region � Close Proximity to US Route 40, Interstate 70, Interstate 470,West Virginia Route 2 & West Virginia Route 88 For More Information, Please Contact: Adam Weidner John Aderholt, Broker [email protected] [email protected] 304.232.5411 304.232.5411 Century Centre � 1233 Main Street, Suite 1500 � Wheeling, WV 26003 960 Penn Avenue, Suite 1001 � Pittsburgh, PA 15222 304.232.5411 � www.century-realty.com SITE I-70 On Ramp 8,000 Vehicles/Day I-70 47,000 Vehicles/Day Ownership has provided the property information to the best of its knowledge, but Century Realty does not guarantee that all information is accurate. All property information should be confirmed before any completed transaction. For More Information, Please Contact: Adam Weidner John Aderholt, Broker [email protected] [email protected] 304.232.5411 304.232.5411 Expansion Space or Drive Thru Potential Drive Thru 8,000 SF Wheeling The 30 Miles to Highlands Washington, PA Pittsburgh Approximately Wheeling 38 Miles Columbus Approximately 136 Miles Ownership has provided the property information to the best of its knowledge, but Century Realty does not guarantee that all information is accurate. -

Marstonmarston Moretaine, Central Bedfordshire Marstonmarston Moretaine, Central Bedfordshire

MarstonMarston Moretaine, Central Bedfordshire MarstonMarston Moretaine, Central Bedfordshire Marston Thrift represents a unique and exciting opportunity to create a viable and sustainable new village community of 2,000 homes close to Marston Moretaine in line with the Central Bedfordshire local plan. What you see here is only the beginning of the journey, we will deliver: • 2,000 new homes, including a range of home types and tenures. We will work with the country’s best housebuilders to craft homes of the highest quality. The range of homes will be designed around fresh air, green space and excellent connections • A 50 bed extra care facility • Two new lower schools and one new middle school, delivered alongside the new homes to cater for the increased demand for school places • A community hub with healthcare, retail, and leisure opportunities • Improved walking, cycling, and public transport facilities, including a dedicated ‘park and change’ facility • An extension to the existing Millennium Country Park, providing a significant new area of open space for new and existing residents to enjoy • A new community woodland delivered in partnership with the Forest of Marston Vale Trust, contributing to the overall objective of increasing woodland within the Marston Vale 1 2 Marston Thrift is not reliant on significant new infrastructure and benefits from the recently completed improvement work carried out on the A421. The site is free from physical constraints, in single ownership and has immediate accessibility to existing transport connections. We are therefore capable of delivering housing early within the plan period, with the first residential completions anticipated within three years, of obtaining an outline planning consent, helping to meet Central Bedfordshire’s strategic housing needs from the outset. -

Geologic Cross Section C–C' Through the Appalachian Basin from Erie

Geologic Cross Section C–C’ Through the Appalachian Basin From Erie County, North-Central Ohio, to the Valley and Ridge Province, Bedford County, South-Central Pennsylvania By Robert T. Ryder, Michael H. Trippi, Christopher S. Swezey, Robert D. Crangle, Jr., Rebecca S. Hope, Elisabeth L. Rowan, and Erika E. Lentz Scientific Investigations Map 3172 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2012 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Ryder, R.T., Trippi, M.H., Swezey, C.S. Crangle, R.D., Jr., Hope, R.S., Rowan, E.L., and Lentz, E.E., 2012, Geologic cross section C–C’ through the Appalachian basin from Erie County, north-central Ohio, to the Valley and Ridge province, Bedford County, south-central Pennsylvania: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3172, 2 sheets, 70-p. -

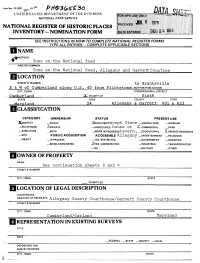

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

:orm No. 10-300 ^0'' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME •^HISTORIC Inns on the National Road AND/OR COMMON Inns on the National Road, Allegany and GarrettCounties LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER to Grantsville & W of Cumberland, a^ong U.S. 40 from Flintstone-NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT .Cumberland Sixth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE 24 Alleaanv & Garrett 001 & 023 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE XDISTRICT —PUBLIC —XoccupiEDexcept Stone _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _=j8UILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED house or X_COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _woRKiNpROGRESstavern, —EDUCATIONAL X_PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE Allegany —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED -XYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME See continuation sheets 3 and STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Allegany County Courthouse/Garrett County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Maryland 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGrNAL SITE GOOD XRUINS only Stone ALTERED MOVED r»ATF *A.R _ UNEXPOSED house or tavern, Allegany DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Eleyen of the inns that served the National Road and the Baltimore Pike in Allegany and Sarrett Counties, Maryland, during the 19th century re main today. ALLEGANY COUNTY The Flints tone Hot e 1 stands on the north side of old Route 10 to the east of Hurleys Branch Road in Flintstone. -

Route of Meriwether Lewis from Harpers Ferry, Va. to Pittsburgh, Pa

Route of Meriwether Lewis from Harpers Ferry, Va. to Pittsburgh, Pa. July 8 – July 15, 1803 by David T. Gilbert National Park Service Harpers Ferry, West Virginia May 5, 2003 (Revised September 28, 2015) Introduction The route which Meriwether Lewis traveled from Harpers Ferry, Virginia to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, between July 8 and July 15, 1803, has not been well documented 1. The only primary source we have is a letter Lewis penned to President Jefferson from Harpers Ferry on July 8, 1803: I shall set out myself in the course of an hour, taking the route of Charlestown, Frankfort, Uniontown and Redstone old fort to Pittsburgh, at which place I shall most probably arrive on the 15th.2 Route of Meriwether Lewis July 8-July 15, 1803 Pittsburgh R Elizabeth E V I Petersons R Brownsville Pennsylvania O I H (Redstone old fort) O Uniontown Farmington POT OMA Cumberland C R IV Grantsville E M R O Maryland Forks of N Cacapon Harpers O N Fort Ashby Ferry G Brucetown A (Frankfort) H E Gainesboro L A Winchester R I West Virginia V Charles Town E R Virginia 1. With the exception of quoted primary sources, this document uses the contemporary spelling, Harpers Ferry, and not the 19th century spelling, Harper’s Ferry. Harpers Ferry was part of Virginia until June 20, 1863, when the state of West Virginia was created by Presidential Proclamation. 2. Meriwether Lewis to Thomas Jefferson, July 8, 1803, quoted in Donald Jackson,Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, With Related Documents, 1783-1854 (Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1979), 106-107. -

AL-III-C-143 Evitts (Evart's) Home Site

AL-III-C-143 Evitts (Evart's) Home Site Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 12-11-2003 ,A1.--111-c....-14'3 Rocky Gap State Park MARYLAND HISTORICAL TRUST Evitts Home Site Evitts Creek Quad INVENTORY FORM FOR STATE HISTORIC SITES SURVEY HISTORIC Evitts Home Site AND/OR COMMON fJLOCATION STREET & NUMBER Rocky Gap State Park CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT VICINITY OF Sixth STATE COUNTY Maryland Allegany DcLAsSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT x_PUBLIC _OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE _MUSEUM -BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE --.XJNOCCUPIED _COMMERCIAL )LPARK -- _STRUCTURE -BOTH _WORK IN PROGRESS _EDUCATIONAL _PRIVATE RESIDENCE _XSITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE J{ENTERTAINMENT _RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS _J(YES RESTRICTED _GOVERNMENT _SCIENTIFIC -BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED _INDUSTRIAL _TRANSPORTATION _NO _MILITARY _OTHER DOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Maryland Department of Natural Resources Telephone #: STREET & NUMBER Taylor Avenue CITY.