Chapter 3 Historic Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide

Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide A Complete Compendium Of RV Dump Stations Across The USA Publiished By: Covenant Publishing LLC 1201 N Orange St. Suite 7003 Wilmington, DE 19801 Copyrighted Material Copyright 2010 Covenant Publishing. All rights reserved worldwide. Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide Page 2 Contents New Mexico ............................................................... 87 New York .................................................................... 89 Introduction ................................................................. 3 North Carolina ........................................................... 91 Alabama ........................................................................ 5 North Dakota ............................................................. 93 Alaska ............................................................................ 8 Ohio ............................................................................ 95 Arizona ......................................................................... 9 Oklahoma ................................................................... 98 Arkansas ..................................................................... 13 Oregon ...................................................................... 100 California .................................................................... 15 Pennsylvania ............................................................ 104 Colorado ..................................................................... 23 Rhode Island ........................................................... -

Transportation

visionHagerstown 2035 5 | Transportation Transportation Introduction An adequate vehicular circulation system is vital for Hagerstown to remain a desirable place to live, work, and visit. Road projects that add highway capacity and new road links will be necessary to meet the Comprehensive Plan’s goals for growth management, economic development, and the downtown. This chapter addresses the City of Hagerstown’s existing transportation system and establishes priorities for improvements to roads, transit, and pedestrian and bicycle facilities over the next 20 years. Goals 1. The city’s transportation network, including roads, transit, and bicycle and pedestrian facilities, will meet the mobility needs of its residents, businesses, and visitors of all ages, abilities, and socioeconomic backgrounds. 2. Transportation projects will support the City’s growth management goals. 3. Long-distance traffic will use major highways to travel around Hagerstown rather than through the city. Issues Addressed by this Element 1. Hagerstown’s transportation network needs to be enhanced to maintain safe and efficient flow of people and goods in and around the city. 2. Hagerstown’s network of major roads is generally complete, with many missing or partially complete segments in the Medium-Range Growth Area. 3. Without upgrades, the existing road network will not be sufficient to accommodate future traffic in and around Hagerstown. 4. Hagerstown’s transportation network needs more alternatives to the automobile, including transit and bicycle facilities and pedestrian opportunities. Existing Transportation Network Known as “Hub City,” Hagerstown has long served as a transportation center, first as a waypoint on the National Road—America’s first Dual Highway (US Route 40) federally funded highway—and later as a railway node. -

For Lease Retail/Office Space 590 National Road, Wheeling, WV 26003

For Lease Retail/Office Space 590 National Road, Wheeling, WV 26003 Property Information � 15,000 SF of retail/office space available | Can be subdivided to 7,000 SF � Former corporate headquarters with custom finished board room and multiple executive offices � Potential build-to-suit - 8,000 SF of office/retail space � Local loan/incentive packages available for relocations � Well maintained commercial space � Elevator served � Signage opportunity on National Road � Over 50 on-site parking spaces � Located in the heart of the Marcellus and Utica Gas Shale region � Close Proximity to US Route 40, Interstate 70, Interstate 470,West Virginia Route 2 & West Virginia Route 88 For More Information, Please Contact: Adam Weidner John Aderholt, Broker [email protected] [email protected] 304.232.5411 304.232.5411 Century Centre � 1233 Main Street, Suite 1500 � Wheeling, WV 26003 960 Penn Avenue, Suite 1001 � Pittsburgh, PA 15222 304.232.5411 � www.century-realty.com SITE I-70 On Ramp 8,000 Vehicles/Day I-70 47,000 Vehicles/Day Ownership has provided the property information to the best of its knowledge, but Century Realty does not guarantee that all information is accurate. All property information should be confirmed before any completed transaction. For More Information, Please Contact: Adam Weidner John Aderholt, Broker [email protected] [email protected] 304.232.5411 304.232.5411 Expansion Space or Drive Thru Potential Drive Thru 8,000 SF Wheeling The 30 Miles to Highlands Washington, PA Pittsburgh Approximately Wheeling 38 Miles Columbus Approximately 136 Miles Ownership has provided the property information to the best of its knowledge, but Century Realty does not guarantee that all information is accurate. -

TRB Special Report 267: Regulation of Weights, Lengths, And

Regulation of Weights, Lengths, and Widths of Commercial Motor Vehicles SPECIAL REPORT 267 TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2002 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE* Chairman: E. Dean Carlson, Secretary, Kansas Department of Transportation, Topeka Vice Chairman: Genevieve Giuliano, Professor, School of Policy, Planning, and Development, University of Southern California, Los Angeles Executive Director: Robert E. Skinner, Jr., Transportation Research Board William D. Ankner, Director, Rhode Island Department of Transportation, Providence Thomas F. Barry, Jr., Secretary of Transportation, Florida Department of Transportation, Tallahassee Michael W. Behrens, Executive Director, Texas Department of Transportation, Austin Jack E. Buffington, Associate Director and Research Professor, Mack-Blackwell National Rural Transportation Study Center, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Sarah C. Campbell, President, TransManagement, Inc., Washington, D.C. Joanne F. Casey, President, Intermodal Association of North America, Greenbelt, Maryland James C. Codell III, Secretary, Kentucky Transportation Cabinet, Frankfort John L. Craig, Director, Nebraska Department of Roads, Lincoln Robert A. Frosch, Senior Research Fellow, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts Susan Hanson, Landry University Professor of Geography, Graduate School of Geography, Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts Lester A. Hoel, L.A. Lacy Distinguished Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University -

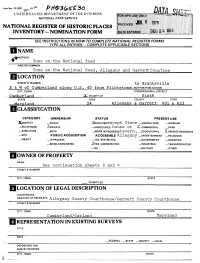

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

:orm No. 10-300 ^0'' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME •^HISTORIC Inns on the National Road AND/OR COMMON Inns on the National Road, Allegany and GarrettCounties LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER to Grantsville & W of Cumberland, a^ong U.S. 40 from Flintstone-NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT .Cumberland Sixth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE 24 Alleaanv & Garrett 001 & 023 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE XDISTRICT —PUBLIC —XoccupiEDexcept Stone _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _=j8UILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED house or X_COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _woRKiNpROGRESstavern, —EDUCATIONAL X_PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE Allegany —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED -XYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME See continuation sheets 3 and STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Allegany County Courthouse/Garrett County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Maryland 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGrNAL SITE GOOD XRUINS only Stone ALTERED MOVED r»ATF *A.R _ UNEXPOSED house or tavern, Allegany DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Eleyen of the inns that served the National Road and the Baltimore Pike in Allegany and Sarrett Counties, Maryland, during the 19th century re main today. ALLEGANY COUNTY The Flints tone Hot e 1 stands on the north side of old Route 10 to the east of Hurleys Branch Road in Flintstone. -

Allegany College of Maryland Facility Is Directly Ahead

2021.directory.pages_Layout 1 10/13/20 10:46 AM Page 21 Board of Trustees Mr. Kim B. Leonard, Chair 3017070123 [email protected] Mrs. Jane A. Belt, ViceChair 3047267261 [email protected] Members Ms. Mirjhana Buck 3017242660 [email protected] Ms. Linda W. Buckel, Esq. 3016975371 [email protected] Ms. Joyce K. Lapp 3012683249 [email protected] Mr. James R. Pyles 2405800865 [email protected] Mr. Barry P. Ronan 2409647236 [email protected] SecretaryTreasurer Dr. Cynthia S. Bambara, 3017845270 [email protected] President Board Staff Ms. Bobbie Cameron Sr. Execuve Associate to the President and Board of Trustees President Phone: 3017845270 Fax: 3017845050 [email protected] 14 2021.directory.pages_Layout 1 10/13/20 10:46 AM Page 22 12401 Willowbrook Road, SE Cumberland, Maryland 21502 3017845005 www.allegany.edu President Dr. Cynthia S. Bambara 3017845270 [email protected] Sr. Execuve Associate to the Ms. Bobbie Cameron 3017845270 [email protected] President & the Board of Trustees VP of Finance and Admin/Facilies Ms. Chrisna Kilduff 3017845221 ckilduff@allegany.edu Sr. VP of Instruconal and Dr. Kurt Hoffman 3017845287 khoff[email protected] Student Affairs VP Advancement and Community Mr.DavidJones 3017845350 [email protected] Relaons/Fundraising Addional MACC Contacts: Student and Legal Affairs Dr. Renee Conner 3017845206 [email protected] Educaonal Services Dr. Connie Clion 3017845429 [email protected] Enrollment Services & Advising Ms. -

Maryland Motor Carrier Handbook Revised DECEMBER 2014 in Cooperation With

Maryland Motor Carrier Handbook Revised DECEMBER 2014 In Cooperation with: Maryland Port Administration Maryland Transportation Authority Maryland State Police Motor Vehicle Administration Public Service Commission Comptroller of Maryland Maryland Department of the Maryland Department of Transportation Environment Maryland Virtual Weigh Station Technology Weight: 103530 lbs Speed: 55.6 mph Length: 64.2 ft Class: 10 Flags: Overweight gross, overweight bridge, overweight axle, overweight tandems VIOLATION Spacing: 4.2 4.2 34.6 4.5 16.7 Axles: Wt.: 16.1 18.9 17.4 20.5 21.3 9.5 Disclaimer: Information contained in the Handbook regarding the various laws and regulations governing commercial motor vehicle operations in Maryland are subject to change without notice. The Handbook is produced solely as a convenience to the public and the State assumes no warranty or representation, either expressed or implied, regarding the information given or the use of any of the material provided or for unintentional omissions, errors, or misprints which appear in the Handbook. On The Cover: Maryland’s Virtual Weigh Station Program is designed to monitor select roadways to assure that vehicles comply with size and weight laws. Enforcement personnel are able to use wireless technology to access the sites remotely and can identify and stop violators. i Maryland Motor Carrier Handbook Survey 1. What do you like about the Handbook? __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ -

Western Pennsylvania History Spring 2016

Up Front This advertisement informs travelers about passage on the National Road Stage Company’s line of coaches. The Reporter, July 22, 1843. sheep, and pigs from western farms to the Meadowcroft markets of Baltimore and Washington, D.C. Wagoners could transport salt, sugar, tea, By Mark Kelly coffee, and iron to western settlements, then Meadowcroft Interpreter/Tour Guide return with whiskey, wool, flour, and bacon much more efficiently in their Conestoga wagons.3 Even though this improved route Carried in Comfortable Coaches made the journey easier for many, the pace Hagerstown, Maryland. An ad in Washington, of travel was still only a few miles an hour. Pa.’s The Reporter on April 30, 1821, states,“The In 1806, Thomas Jefferson signed “An Act to For those who could afford it, stage coaches arrangement of this line, will secure a Regulate the Laying Out and Making a Road offered speedy travel between cities in the East passenger a safe conveyance from Wheeling to from Cumberland in the State of Maryland, to and the Midwest. Philadelphia (a distance of 346 miles) in a little the State of Ohio.”1 This road would ease the The earliest stage lines spanned the more than four days.”6 The pair continued to journey of settlers moving west by improving 131-mile-trip from Cumberland to Wheeling expand their operations west, establishing the part of the existing road cut by British in four different sections, but ran only three National Road Stage Company in Uniontown General Edward Braddock in 1755, and link times each week.4 These original lines, bought around 1824. -

WESTERN MARYLAND COLLEGE BULLETIN 1954 Annual Catalogue

%e WESTERN MARYLAND COLLEGE BULLETIN 1954 - Annual Catalogue fJlie WESTERN MARYLAND COLLEGE BULLETIN Eighty-seventh V'fnnual Catalogue Westminster, Maryland Volume XXXV March, 1954 Number 3 W... tem M,u:y)..nd Coll""e Bulletin, Westminster, M..ryhlnd, published monthly dudnll' the ~ch<><>lye..r from JanUary to November and July.August. except May, June and S~ptember, by the Coll"",e. Entered as """ond e\au mutter. Ma,. 19. 1921, at the p""t Office ..t W""tmin.ter, Md., under the act of August 24, 1912. Accepted for mailinll' at Bl)eeial r..te of poswge provided. for in seetion llOS, net of October 3. 1911. CONTENTS PACE COLLEGECALF:NDARFOR '954-1955------------------------ AN INTROOUCTION TO WESTERN MARYLAND COLLEGE _ ADMINISTRATION II Board of TrusteeL_____ 12' Administration and Staff___________________________ 14 Faculty 15 FACILITLES 23 Residentiali~~r:t~~~:l~~~_~!_~~~_:~~~~~====================24-:~26 Health and Physical Welfarc_______________________ 27 General 28 FROM ADMISSION TO GRADUATION________________________ 29 Admission ~1 Grades and Reports __ 32 Degrees 34 The Acclerated Program 36 Graduation Honors 36 Awards 37 Preparation for High School Teaching______________ 38 GENERAL INFORMATTON 39 Extracurricular Activities 41 Expenses 43 Scholarships 44 COURSES OF INSTRUCTION 47 ANNUAL REGISTER 107 Student Register for the Year 1953-1954-------------- 109 Recapitulation of Students 130 Degreesand Honors Conferred in '953--------------- 131 Western Maryland College Alumni Association 139 Recapitulation of GraduateS- 140 Endowments 143 Calendar 1954 [ 4 1 'THE COLLEGE CALENDAR SUMMER SESSION 1954 June 21, Monday 8:30 A. M.-12:00 M. Registration for First Term. 1:00 P. M. First Term classes begin. July 24. -

Nneka Willis-Gray

One Center Plaza 120 West Fayette Street Baltimore, MD 21201 Boyd K. Rutherford Larry Hogan Sam Abed Lt. Governor Governor Secretary AMENDMENT NO. 1 INVITATION FOR BIDS (IFB) SMALL PROCUREMENT FOR OPTOMETRY SERVICES Solicitation No. 19-SH-004 July 12, 2018 The following Amendment is being issued to amend certain information contained in the above-named IFB. All information contained herein is binding on all Bidders who respond to this solicitation. New language has been double underlined and marked in red bold, (e.g., new language). Language deleted has been marked with a double strikethrough (e.g., language deleted). 1. Revise 2.1 (Background and Purpose) as follows: 2.1.5 The State is issuing this solicitation for the purpose of procuring optometry services for a six (6) month period, beginning on or about August 1, 2018 – January 31, 2019, for youth at eight (8) DJS facilities. The Department intends to make up to three (3) awards, one for each Functional Area as described in Section 2.2.1. A bid may be submitted for more than one Functional Area. A Bidder shall provide services in all locations in a Functional Area. 2. Revise Section 2.2.1 (Locations) as follows: The Contractor shall provide optometry services, on-site services in the medical suite of the health center at each of the following locations: A. FUNCTIONAL Baltimore City Charles H. Hickey, Alfred D. Noyes AREA I Juvenile Justice Jr. School(Hickey) Children’s Center Center (BCJJC) 9700 Old Harford (Noyes); 9925 300 North Gay St. Rd. Blackwell Road Baltimore, MD 21202 Baltimore, MD Rockville, MD 21234 20850 Thomas J.S. -

Surviving Maryland Railroad Stations

Surviving Maryland Railroad Stations Baltimore : The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad's Mount Royal Station, Camden Station and Mount Clare Station all still stand. Also, two former B&O office buildings remain. Also, two former Pennsylvania Railroad and one Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington Railroad (PRR subsidiary) passenger station still stand. Lastly, a Maryland & Pennsylvania Railroad freight depot remains. Aberdeen : Originally built by the B&O, to be restored (last known wooden depot standing designed by architect Frank Furness). Also, the former PRR passenger station here still stands, used as an Amtrak/MARC stop. Airey : Originally built by the Dorchester & Delaware Railroad, privately owned. Alesia : Originally built by the Western Maryland Railway, used as apartments. Antietam Station : Originally built by the Norfolk & Western Railway, used as a museum. Barclay : Originally built by the Queen Anne & Kent Railroad, privately owned and moved to Sudlersville. Bethlehem : Originally built by the Baltimore, Chesapeake & Atlantic Railway, privately owned. Blue Mount : Originally built by the Pennsylvania Railroad, privately owned. Boring : Originally built by the Western Maryland Railway, used as a post office. Bowie : Originally built by the PRR, used as a museum. Also, the former PRR freight depot here still stands, used as a museum. Brooklandville : Originally built by the PRR, privately owned. Also, the former Baltimore & Susquehanna Railroad depot here still stands, used as a business. Brunswick : Originally built by the B&O, used as a MARC stop. Bynum : Originally built by the Ma & Pa, privately owned. Cambridge : Originally built by the Dorchester & Delaware Railroad, used as a business. Centreville : The original Queen Anne & Kent Railroad freight depot here still stands. -

2016 Annual Report of the Maryland Historical Trust July 1, 2015 - June 30, 2016 Maryland Department of Planning

2016 Annual Report of the Maryland Historical Trust July 1, 2015 - June 30, 2016 Maryland Department of Planning Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Department of Planning 100 Community Place Crownsville, MD 21032-2023 410-697-9591 www.planning.maryland.gov www.MHT.maryland.gov Table of Contents The Maryland Historical Trust Board of Trustees 2 Who We Are and How We Work 3 Maryland Heritage Structure Rehabilitation Tax Credit 5 Maryland Heritage Areas Program 9 African American Heritage Preservation Program 15 Architectural Research and Survey 16 Terrestrial Archeological Research and Survey 18 Maritime Archeological Research and Survey 20 Preservation Planning 22 Cultural Resources Hazard Mitigation Planning Program 24 Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum 26 Historic Preservation Easements 28 State and Federal Project Review 33 Military Monuments and Roadside Historical Markers 34 Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory 36 Public Archeology Programs 38 Cultural Resource Information Program 41 Maryland Preservation Awards 42 The Maryland Historical Trust Board of Trustees The Maryland Historical Trust is governed by a 15-member Board of Trustees, including the Governor, the Senate President and the House Speaker or their designees, and 12 members appointed by the Governor. At least two trustees must be qualified with an advanced degree in archeology or a closely related field and shall have experience in the field of archeology. Of the trustees qualified in the field of archeology, at least one must have experience in the field of submerged archeology and at least one must have experience in the field of terrestrial archeology. The term of a member is 4 years. Trustees Appointed by the Governor: Albert L.