Malandragem and Ginga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hubobrasileñostriunfalesdesdeeldía1

6 BARÇA MUNDO DEPORTIVO Martes 11 de junio de 2013 Hubo brasileños triunfales desde el día 1 Neymar, tranquilo: de Evaristo aMoura, el salto aEuropa puede ser exitoso desde el principio Del Palmeiras pasó al Depor en 1996. Un solo año, pero para enmarcar: 21 goles en 41 partidos lo llevaron al Barça. 6 BARÇA JUNINHO MUNDO DEPORTIVO Martes 11 de junio de 2013 PERNAMBUCANO (Lyon, Hubo brasileños2001) Rivaldotriunfaleslo recomendódesdeal el día 1 Neymar, tranquilo: de EvaristoBarçaaMoura,peroel saltoel LyonaEuropasí sepuededecidió:ser exitoso desde el principio Del Palmeiras pasó al Depor en lo fichó en 2001. Estuvo hasta 1996. Un solo año, pero para enmarcar: 21 goles en 41 2009. Se fue siendo el cuarto partidos lo llevaron al Barça. JUNINHO PERNAMBUCANO (Lyon, goleador de su historia ycon 7 2001) Rivaldo lo recomendó al Barça pero el Lyon sí se decidió: lo fichó en 2001. Estuvo hasta Textos: Xavier Muñoz Ligas. Un medio que marcó 2009. Se fue siendo el cuarto goleador de su historia ycon 7 Textos: Xavier Muñoz Ligas. Un medio que marcó 100 goles, 44 de falta. Mito en 100 goles, 44 de falta. Mito en n Friedenreich, Leonidas, Gerland. n Friedenreich, Leonidas, Zizinho, Garrincha. Pelé... Hubo una época en que casi Gerland. LUCIO (B. Leverkusen, todos los grandesfutbolis- 2001) Jugaba en el Inter de Zizinho, Garrincha. Pelé... tas brasileños completaban Porto Alegre yRexach lo quiso su carrerasin salir del país. para el Barça, pero el Bayer Hoy todohacambiado. In- fichó aeste central que se Hubo una época en que casi cluso en pleno milagro eco- adaptó pronto (marcó 5goles nómico brasileño, lo habi- LUCIO (B. -

O MOMENTO NACIONAL! D. MOIS~Oêlflo REGISTA-SE HOJE O ANI• \S Alterações PRODUZIDAS NO REGULA~ VERSÃRIO NATALICIO DE ME-NTO DO Ilviposto DE CONSUMO S, EXC

Adm!nllltração e Oficinas 1!:dltfclo dl\ Impr,n,a Ofletal PffiETOR oa•JB IIAaBOIA J oão Pe3eôa -· ·- Parafba OSRENTS Rua Duque do CuJu / r: CAVALCANTJ l==' l ANO XLVI .JO.,O P ES~OA - Sexta-feira. R de ahr il de 19:l~ ~·--.~ • vj J- Nl' MERO i9 o MOMENTO NACIONAL! D. MOIS~OÊLflO REGISTA-SE HOJE O ANI• _\S ALTERAÇõES PRODUZIDAS NO REGULA~ VERSÃRIO NATALICIO DE ME-NTO DO IlVIPOSTO DE CONSUMO S, EXC. REYDMA, te da G ... Região :\filí~a r. aquartch Regi,c.;t..1-.,t- 11a data ele hoje o ;J.niver- o ministro Osvaldo Aranha e o general Góis Monteiro da em Curitiba ,\ S HOi\-lE~A GEXS A O PRl!.$1J>E.. - :;ál'io ·uatulicio cio exmo. d. Moisé,s visitaram as legações argentina, chilena e uruguaia, no TE GETúLIO \ 'ARGAS EM ~ 1 Coêlho. a1Teb1,.c,po metropolitano rla LO l 'RE\'CO Rio de Janeiro - As homenagens ao presidente Getúlio 1 Paraíba SAO LOURE~ÇO, 7 t.\ ~. 1 - O Figura tnünente do rléJO brastleil·o vargas em S, Lourenço - Vão ao Rio de Janeiro os ln· pr eJS1denle Getúlio \'argas conti nú,1 tetv~ntores federais no Ceará e no Rio Grande do Sul ~emlo a lvu d e signifkaliv!l.S homen a s. excia revdma. apesar da sua mdole !!Cns nesta cida de mode.srn.. 1mpoz-sc• a ef..Sn projPção ne O ntem o gon.•rna dor Benedito_ V l • 1 las strns exeepdonais virtudf>:- de sa• RIO, 7 1 \ N ) - Dê..,c1c a apro,,,- uma. \'isita ás leg.~~·ões do Chil e . -

Schedule F-2 by Last Name

Schedule F-2 by Last Name ID Country Name Country Code Last Name, First Contingent Unliquidated Disputed Amount 956503 Norway (NO) Y ANA, ENRIQUE X X X UNKNOWN 484961 Dominican Republic (DO) Y COBOL GHZ, TFJFDGHDGLK X X X UNKNOWN 486618 Dominican Republic (DO) Y DG Y XYGUHJ, VB FTXGUJFJGI X X X UNKNOWN 896390 Mexico (MX) Y EJE, FRUFRÚ X X X UNKNOWN 486171 Dominican Republic (DO) Y FN DG, UN GC IBB FIN X X X UNKNOWN 908979 Mexico (MX) Y FUTURO, QUITO X X X UNKNOWN 424350 Dominican Republic (DO) Y FYFGJGFN, JJGHFHFHFH X X X UNKNOWN 423393 Dominican Republic (DO) Y G YHHJH, JFHGJHXHG X X X UNKNOWN 412443 Dominican Republic (DO) Y GT CYGYF, GFHCHJGHH X X X UNKNOWN 1324929 Ukraine (UA) Y HG, Y GG X X X UNKNOWN 732427 Hong Kong (HK) Y HGT, YFKM X X X UNKNOWN 1289235 Tunisia (TN) Y HOTEL, Y TABÙ X X X UNKNOWN 1038248 Peru (PE) Y HURTADO, MARIA DOLORES X X X UNKNOWN 821305 Japan (JP) Y INAGAKI, ELENA YASSUKO X X X UNKNOWN 640809 Spain (ES) Y L, J O X X X UNKNOWN 766039 India (IN) Y LAKSHMI DEVI X X X UNKNOWN 922077 Malaysia (MY) Y MEE, YONG X X X UNKNOWN 1408376 United States (US) Y MOHAMUD, ASHA X X X UNKNOWN 1577915 United States (US) Y MORA, LIBY X X X UNKNOWN 731473 Hong Kong (HK) Y MUTNYBRTVRC, UJYNRBTE X X X UNKNOWN 446711 Dominican Republic (DO) Y RECURSO, M X X X UNKNOWN 270807 Colombia (CO) Y ROBIN, BATMAN X X X UNKNOWN 890738 Mexico (MX) Y SUS MUJERES, AUGUSTO X X X UNKNOWN 893745 Mexico (MX) Y SUS, DUDAD X X X UNKNOWN 707048 United Kingdom (GB) Y TRA, NNI X X X UNKNOWN 1794135 Uruguay (UY) Y TRE, NMKLOJ X X X UNKNOWN 48893 Bolivia -

Commutation Denials by President Barack H. Obama

President Barack H. Obama October 11, 2010 Commutation Denials Acosta, Lazaro Acosta-Beltran, Cesar Aguayo-Renteria, Gustavo Aguilar-Torre, Maria Elisa Aguirre-Saenz, German Aguirre-Torres, Eugenio Alarcon-Solano, Pablo Alberteris, Arsenio Alcazar, Armando Alva-Diaz, Candido Alvarado, Luis Alvarez, Cervando Alvarez, Manuel Camacho Alvarez, Martin Alvarez-Hernandez, Efren Carmen Anderson, Lucy Marie Anderson, Marc Anthony Anderson, Raymond Anderson, Walter C. Angulo-Luango, Efren Angulo-Mendoza, Juan Diego Arce, Jhon Jairo Arceo-Rodriguez, Fernando Arevalo, Nahum Antonio Arguelles, Javier; aka Arguelles-Rodriguez, Javier Armendariz, Scott Jordan Arredondo-Meza, Rigoberto Arroyo, Jaime Zendejas Arroyo-Obando, Francisco Asensio-Boyadzhyan, Zoyla Isolina Austin, Jeannie Marie Avalos-Perez, Jose de Jesus Avalos-Zavala, Dimas Avellaneda-Estrada, Leonel Avellaneda-Gama, Homero Ayala-Guadarrama, Kain Bagby, Michelle E. Bajo-Ramirez, Heriberto Baldovinos, Pedro C. Ballesteros-Esparaza, Jesus Jose Balobeck, Gary Anthony Banuelos, Louie Carlos Barajas, Jose Juan; aka Barajas-Torres, Jose Juan Barnes, Lakisha Nicole Barnett, Douglas Wayne Barragan-Alvarez, Adalberto President Barack H. Obama October 11, 2010 Commutation Denials Barraza, Maximino Jimenez Barrientos-Ramos, Jose Luis Barrios, Lazaro Barron-Aguilera, Erick Bass, Danny Kay Bass, John Baussan, Nick Anzoil Bejarano-Saenz, Israel Benavides-Rodriguez, Rene Benval, Alberto Mojica Bernandino-Mejia, Carlos Bevil, Craig Larry Biggins, Mark John Billings, Anthony Wayne Bingham, Christopher Paul -

O Marketing Pessoal Feito Por Integrantes De Bandas De Pagode Em Redes De Relacionamentos1

Intercom – Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos Interdisciplinares da Comunicação X Congresso de Ciências da Comunicação na Região Sul – Blumenau – 28 a 30 de maio de 2009 A Malandragem no Orkut: O Marketing Pessoal Feito Por Integrantes de Bandas de Pagode Em Redes De Relacionamentos1 Camila Reck Figueiredo2 Danielle Xavier Miron3 Najara Ferrari Pinheiro4 Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, UFSM, Santa Maria, RS Centro Universitário Franciscano, UNIFRA, Santa Maria, RS Universidade de Caxias do Sul, UCS, Caxias do Sul, RS. Resumo O presente artigo aborda a relação entre internet e os espaços digitais que surgiram com seu advento: as comunidades virtuais e as redes de relacionamentos. Também constitui este artigo o marketing pessoal em perfis criados na rede de relacionamento Orkut. Para fazer este artigo, foi utilizada pesquisa bibliográfica e configurações empíricas da pesquisa da comunicação, como abordagens de teor cartográfico (mapeamento de elementos existentes na rede) e abordagens de teor textual (análise de palavras, objetos sonoros, imagens e outras linguagens). Este estudo selecionou cinco perfis de integrantes de bandas de pagode de Santa Maria/RS. Como resultado, pode-se perceber que todos os perfils analisados reafirmam a identidade de pagodeiros natos, relacionando esse grupo com mulheres, bebidas e futebol. Palavras-chave Multimídia; Tecnologia; Cultura; Orkut; Marketing Pessoal 1. Internet e Espaços Digitais O século XX ficou marcado como um período de grande evolução cientifica e tecnológica. Essa evolução gerou também mudanças para a vida humana. O desenvolvimento tecnológico, segundo Steffen (2005), se refletiu nas tecnologias de comunicação, com o surgimento e desenvolvimento do rádio, do cinema, da televisão, a popularização dos jornais, das revistas e, no final do século, com o surgimento de uma nova mídia: a Internet. -

Domination and Resistance in Afro-Brazilian Music

Domination and Resistance In Afro-Brazilian Music Honors Thesis—2002-2003 Independent Major Oberlin College written by Paul A. Swanson advisor: Dr. Roderic Knight ii Table of Contents Abstract Introduction 1 Chapter 1 – Cultural Collisions Between the Old and New World 9 Mutual Influences 9 Portuguese Independence, Exploration, and Conquest 11 Portuguese in Brazil 16 Enslavement: Amerindians and Africans 20 Chapter 2 – Domination: The Impact of Enslavement 25 Chapter 3 – The ‘Arts of Resistance’ 30 Chapter 4 – Afro-Brazilian Resistance During Slavery 35 The Trickster: Anansi, Exú, malandro, and malandra 37 African and Afro-Brazilian Religion and Resistance 41 Attacks on Candomblé 43 Candomblé as Resistance 45 Afro-Brazilian Musical Spaces: the Batuque 47 Batuque Under Attack 50 Batuque as a Place of Resistance 53 Samba de Roda 55 Congadas: Reimagining Power Structures 56 Chapter 5 – Black and White in Brazil? 62 Carnival 63 Partner-dances 68 Chapter 6 – 1808-1917: Empire, Abolition and Republic 74 1808-1889: Kings in Brazil 74 1889-1917: A New Republic 76 Birth of the Morros 78 Chapter 7 – Samba 80 Oppression and Resistance of the Early Sambistas 85 Chapter 8 – the Appropriation and Nationalization of Samba 89 Where to find this national identity? 91 Circumventing the Censors 95 Contested Terrain 99 Chapter 9 – Appropriation, Authenticity, and Creativity 101 Bossa Nova: A New Sound (1958-1962) 104 Leftist Nationalism: the Oppression of Authenticity (1960-1968) 107 Coup of 1964 110 Protest Songs 112 Tropicália: the Destruction of Authenticity (1964-1968) 115 Chapter 10 – Transitions: the Birth of Black-Consciousness 126 Black Soul 129 Chapter 11 – Back to Bahia: the Rise of the Blocos Afro 132 Conclusions 140 Map 1: early Portugal 144 Map 2: the Portuguese Seaborne Empire 145 iii Map 3: Brazil 146 Map 4: Portuguese colonies in Africa 147 Appendix A: Song texts 148 Bibliography 155 End Notes 161 iv Abstract Domination and resistance form a dialectic relationship that is essential to understanding Afro-Brazilian music. -

Mestiçagem, Malandragem, E Antropofagia: How Forró Is Emblematic of Brazilian National Identity

Megwen Loveless [email protected] Harvard University www.harvard.edu 2004 ILASSA conference UT – Austin. Mestiçagem, Malandragem, e Antropofagia: How Forró Is Emblematic of Brazilian National Identity A relatively recent cultural phenomenon (dating from the mid-twentieth century), forró music arose in the Brazilian northeast “backlands” and has since developed into a national “treasure” of folkloric “tradition.” This paper – part of a much larger ethnographic project - seeks to situate a particular style of forró music at the epicenter of an “imagined community” which Brazilians look toward as a major source of national identity. In this presentation I will show that mestizagem, malandragem, and antropofagia - three traditions conspicuously present in any scholarly discussion of Brazilian identity – are strikingly present in forró music and performance, making forró emblematic of national identity for a large part of the Brazilian population. Forró, a modern rural music, takes its name from a nineteenth-century dance form called forróbodo. Like other young Brazilian musics, it is constantly evolving, though a “traditional” base line has been conserved by several “roots” bands – it is this “traditional” music, called forró pé-de-serra, that provides the soundtrack to the imagined community1 through which I claim many Brazilians reinforce their national identity. The pé-de-serra style is generally played by three-piece bands including an accordion, a triangle, and a double-headed bass drum called the “zabumba.” (The two more recent – and quite popular - styles which I have not linked to my analysis are more synthesized versions called forró universitário and forró estilizado.) While credit for developing present-day forró goes to Luis Gonzaga, its genealogy traces back many more generations to the zabumba ensemble groups of the northeast, which featured the forementioned bass drum along with several fife and fiddle players. -

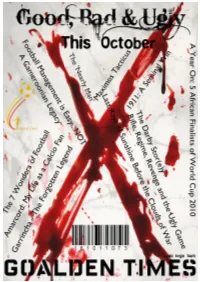

Goalden Times: October, 2011 Edition

Goalden Times October 2011 Page 0 qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyu Goalden Times Declaration: The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the authors of the respective articles and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Goalden Times. All the logos and symbols of teams are the respective trademarks of the teams and national federations. The images are the sole property of the owners. However none of the materials published here can fully or partially be used without prior written permission from Goalden Times. If anyone finds any of the contents objectionable for any reasons, do reach out to us at [email protected]. We shall take necessary actions accordingly. Cover Illustration: Srinwantu Dey Logo Design: Avik Kumar Maitra Design and Concepts: Tulika Das Website: www.goaldentimes.org Email: [email protected] Facebook: GOALden Times http://www.facebook.com/pages/GOALden-Times/160385524032953 Twitter: http://twitter.com/#!/goaldentimes October 2011 Page 1 Goalden Times | Edition III | First Whistle…………4 Goalden Times is a ‘rising star’. Watch this space... Garrincha – The Forgotten Legend …………5 Deepanjan Deb pays a moving homage to his hero in the month of his birth Last Rays of Sunshine Before the Clouds of War…………9 In our Retrospective feature - continuing our journey through the history of the World Cup, Kinshuk Biswas goes back to the last World Cup before World War II 1911 – A Seminal Win …………16 Kaushik Saha travels back in time to see how a football match influences a nation’s fight for freedom Amarcord: My Life as a Calcio Fan…………20 We welcome Annalisa D’Antonio to share her love of football and growing up stories of fun, frolic and Calcio This Month That Year…………23 This month in Football History Rifle, Regime, Revenge and the Ugly Game…………27 Srinwantu Dey captures a vignette of stories where football no longer remained ‘the beautiful game’ Scouting Network…………33 A regular feature - where we profile an upcoming talent of the football world. -

Kahlil Gibran a Tear and a Smile (1950)

“perplexity is the beginning of knowledge…” Kahlil Gibran A Tear and A Smile (1950) STYLIN’! SAMBA JOY VERSUS STRUCTURAL PRECISION THE SOCCER CASE STUDIES OF BRAZIL AND GERMANY Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Susan P. Milby, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Melvin Adelman, Adviser Professor William J. Morgan Professor Sarah Fields _______________________________ Adviser College of Education Graduate Program Copyright by Susan P. Milby 2006 ABSTRACT Soccer playing style has not been addressed in detail in the academic literature, as playing style has often been dismissed as the aesthetic element of the game. Brief mention of playing style is considered when discussing national identity and gender. Through a literature research methodology and detailed study of game situations, this dissertation addresses a definitive definition of playing style and details the cultural elements that influence it. A case study analysis of German and Brazilian soccer exemplifies how cultural elements shape, influence, and intersect with playing style. Eight signature elements of playing style are determined: tactics, technique, body image, concept of soccer, values, tradition, ecological and a miscellaneous category. Each of these elements is then extrapolated for Germany and Brazil, setting up a comparative binary. Literature analysis further reinforces this contrasting comparison. Both history of the country and the sport history of the country are necessary determinants when considering style, as style must be historically situated when being discussed in order to avoid stereotypification. Historic time lines of significant German and Brazilian style changes are determined and interpretated. -

Redalyc.YES, WE ALSO CAN! O DESENVOLVIMENTO DE INICIATIVAS DE CONSUMO COLABORATIVO NO BRASIL

Revista Base (Administração e Contabilidade) da UNISINOS E-ISSN: 1984-8196 [email protected] Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos Brasil MAURER, ANGELA MARIA; SCHMITT FIGUEIRÓ, PAOLA; ALVES PACHECO DE CAMPOS, SIMONE; SEBASTIÃO DA SILVA, VIRGÍNIA; DE BARCELLOS, MARCIA DUTRA YES, WE ALSO CAN! O DESENVOLVIMENTO DE INICIATIVAS DE CONSUMO COLABORATIVO NO BRASIL Revista Base (Administração e Contabilidade) da UNISINOS, vol. 12, núm. 1, enero-marzo, 2015, pp. 68-80 Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos São Leopoldo, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=337238452007 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto BASE – Revista de Administração e Contabilidade da Unisinos 12(1):68-80, janeiro/março 2015 2015 by Unisinos - doi: 10.4013/base.2015.121.06 YES, WE ALSO CAN! O DESENVOLVIMENTO DE INICIATIVAS DE CONSUMO COLABORATIVO NO BRASIL YES, WE ALSO CAN! THE DEVELOPMENT OF COLLABORATIVE CONSUMPTION INITIATIVES IN BRAZIL ANGELA MARIA MAURER [email protected] RESUMO O avanço e disseminação das tecnologias de informação e comunicação proporcionam o surgi- PAOLA SCHMITT FIGUEIRÓ [email protected] mento de novas formas de compartilhamento e a ascensão de plataformas de práticas coletivas que contribuem para o desenvolvimento de novas formas de consumo, como o consumo colabo- SIMONE ALVES PACHECO rativo. Este tipo de consumo descreve a prática de partilha, empréstimos comerciais, aluguel e DE CAMPOS trocas realizados, principalmente, no ciberespaço. -

Diego Forlán Collects

DIEGO FORLAN Uruguay & Atlético Madrid Golden Ball winner at FIFA World Cup 2010™ ENGLISH LANGUAGE Story: Diego Forlán collects adidas Golden Ball Award for best player at FIFA World Cup 2010 Location: Madrid, Spain Date: Dec 2010 Duration: 03’20’’ Restrictions: Free to air material for all media & platforms Language: English Format: Pal 16:9 Script: Uruguay’s Diego Forlán collects adidas Golden Ball trophy for the best player of the FIFA World Cup™. Forlán netted five goals at the event and established himself as the most dangerous player on the pitch in each game he played. The 31-year old Atletico Madrid player follows Zinedine Zidane, Oliver Khan and Ronaldo in the list of past winners. Asked about recent speculation of a move from his current La Liga club Atletico Madrid Forlán admitted the stories were not true. He said he was used to hearing ‘rumours’ of his impending transfer, ususally for the first time on the TV news. Forlán believes Barcelona and Real Madrid have a little bit of an advantage over the other teams in La Liga because they have, “plenty of money to buy very good players.” Full list of past Golden Ball winners: 1930 Jose Nasazzi (Uruguay) 1934 Giuseppe Meazza (italy) 1938 Leonidas (Brazil) 1950 Zizinho (Brazil) 1954 Ferenc Puskas (Hungary) 1958 Didi (Brazil) 1962 Garrincha (Brazil) 1966Bobby Charlton(England) 1970Pele(Brazil) 1974Johan Cruijff(Netherlands) 1978Mario Kempes (Argentina) 1982Paulo Rossi (Italy) 1986Diego Maradona (Argentina) 1990Salvatore Schillaci (Italy) 1994Romario (Brazil) 1998Ronaldo (Brazil) 2002Oliver Kahn (Germany) 2006Zinedine Zidane(France) 2010Diego Forlán (Uruguay) INTERVIEW: Diego Forlán Q. When you were told that you won this award, how did you feel? Well it’s unbelievable because if you think about all the players that were dreaming of the World Cup and trying to play well with their national teams and you get the chance to win it. -

The Social and Cultural Effects of Capoeira's Transnational Circulation in Salvador Da Bahia and Barcelona

The Social and Cultural Effects of Capoeira’s Transnational Circulation in Salvador da Bahia and Barcelona Theodora Lefkaditou Aquesta tesi doctoral està subjecta a la llicència Reconeixement 3.0. Espanya de Creative Commons. Esta tesis doctoral está sujeta a la licencia Reconocimiento 3.0. España de Creative Commons. This doctoral thesis is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0. Spain License. Departamento de Antropología Cultural e Historia de América y de África Facultad de Geografía e Historia Universidad de Barcelona Programa de Doctorado en Antropología Social y Cultural Bienio 2005-2007 The Social and Cultural Effects of Capoeira’s Transnational Circulation in Salvador da Bahia and Barcelona Tesis de Doctorado Theodora Lefkaditou Director: Joan Bestard Camps Marzo 2014 To Antonio and Alaide ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is the beginning and the end of a journey; of an ongoing project I eventually have to abandon and let go. I would like to thank all the people who contributed along the way. Most immediately, I am grateful to my supervisor, Professor Joan Bestard Camps, for his patience, guidance and expertise and for encouraging me to discover anthropology according to my own interests. I must also acknowledge the encouragement I received from Professor Manuel Ruiz Delgado. My thanks extend to all members of the Doctorate Program in Social and Cultural Anthropology (2007- 2009) of the Department of Cultural Anthropology and History of America and Africa at the University of Barcelona for their useful feedback in numerous occasions. They all have considerably enriched my anthropological knowledge. I am also grateful to Professor Livio Sansone and Professor James Carrier for their comments and suggestions; Professor João de Pina Cabral for his recommendations and Dr.