The Nauvoo Rescue Missions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joseph Smith Ill's 1844 Blessing Ana the Mormons of Utah

Q). MicAael' J2umw Joseph Smith Ill's 1844 Blessing Ana The Mormons of Utah JVlembers of the Mormon Church headquartered in Salt Lake City may have reacted anywhere along the spectrum from sublime indifference to temporary discomfiture to cold terror at the recently discovered blessing by Joseph Smith, Jr., to young Joseph on 17 January 1844, to "be my successor to the Presidency of the High Priesthood: a Seer, and a Revelator, and a Prophet, unto the Church; which appointment belongeth to him by blessing, and also by right."1 The Mormon Church follows a line of succession from Joseph Smith, Jr., completely different from that provided in this document. To understand the significance of the 1844 document in relation to the LDS Church and Mormon claims of presidential succession from Joseph Smith, Jr., one must recognize the authenticity and provenance of the document itself, the statements and actions by Joseph Smith about succession before 1844, the succession de- velopments at Nauvoo after January 1844, and the nature of apostolic succes- sion begun by Brigham Young and continued in the LDS Church today. All internal evidences concerning the manuscript blessing of Joseph Smith III, dated 17 January 1844, give conclusive support to its authenticity. Anyone at all familiar with the thousands of official manuscript documents of early Mormonism will immediately recognize that the document is written on paper contemporary with the 1840s, that the text of the blessing is in the extraordinar- ily distinctive handwriting of Joseph Smith's personal clerk, Thomas Bullock, that the words on the back of the document ("Joseph Smith 3 blessing") bear striking similarity to the handwriting of Joseph Smith, Jr., and that the docu- ment was folded and labeled in precisely the manner all one-page documents were filed by the church historian's office in the 1844 period. -

The Mormon Trail

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2006 The Mormon Trail William E. Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hill, W. E. (1996). The Mormon Trail: Yesterday and today. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MORMON TRAIL Yesterday and Today Number: 223 Orig: 26.5 x 38.5 Crop: 26.5 x 36 Scale: 100% Final: 26.5 x 36 BRIGHAM YOUNG—From Piercy’s Route from Liverpool to Great Salt Lake Valley Brigham Young was one of the early converts to helped to organize the exodus from Nauvoo in Mormonism who joined in 1832. He moved to 1846, led the first Mormon pioneers from Win- Kirtland, was a member of Zion’s Camp in ter Quarters to Salt Lake in 1847, and again led 1834, and became a member of the first Quo- the 1848 migration. He was sustained as the sec- rum of Twelve Apostles in 1835. He served as a ond president of the Mormon Church in 1847, missionary to England. After the death of became the territorial governor of Utah in 1850, Joseph Smith in 1844, he was the senior apostle and continued to lead the Mormon Church and became leader of the Mormon Church. -

Mormons and the Ecological Geography Of

Changes in the West : Mormons and the ecological geography of nationalism by Willard John McArthur A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Montana State University © Copyright by Willard John McArthur (1999) Abstract: Environmental historians have made fruitful endeavors in exploring the ways in which human communities modify the landscapes in which they live. However, nationalism is one area that has exhibited a tremendous influence on the course of modem history, yet has been little studied in its relationship to the environment. This thesis looks at the ways in which nationalism-a sense of connection to the larger nation— has influenced those modifications, and how those modifications have influenced and affected those making changes. This thesis looks to the early Mormon migrants to the West as a case study on how nationalism has influenced environmental change. Using an interdisciplinary approach, this argument relies on the work of intellectual historians of nationalism, environmental historians, geographers, and ecologists\biologists. Using these studies as a framework, this thesis posits a method for identifying nationalized landscapes: recognizing circumscribed landscapes, simplified environments, and lands that are connected spatial and temporally to the larger nation identifies a nationalized landscape. In particular, this thesis looks at fish, trees, and riparian zones as areas of change. Using the identifying markers of circumscription, simplification, and connection has uncovered that Mormons did indeed make changes in the landscape that were influenced by nationalism. These changes made to the land, influenced by nationalism, created a redesigned nature, that in turn influenced human relationships. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986

Journal of Mormon History Volume 13 Issue 1 Article 1 1986 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1986) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 13 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol13/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986 Table of Contents • --Mormon Women, Other Women: Paradoxes and Challenges Anne Firor Scott, 3 • --Strangers in a Strange Land: Heber J. Grant and the Opening of the Japanese Mission Ronald W. Walker, 21 • --Lamanism, Lymanism, and Cornfields Richard E. Bennett, 45 • --Mormon Missionary Wives in Nineteenth Century Polynesia Carol Cornwall Madsen, 61 • --The Federal Bench and Priesthood Authority: The Rise and Fall of John Fitch Kinney's Early Relationship with the Mormons Michael W. Homer, 89 • --The 1903 Dedication of Russia for Missionary Work Kahlile Mehr, 111 • --Between Two Cultures: The Mormon Settlement of Star Valley, Wyoming Dean L.May, 125 Keywords 1986-1987 This full issue is available in Journal of Mormon History: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol13/iss1/ 1 Journal of Mormon History Editorial Staff LEONARD J. ARRINGTON, Editor LOWELL M. DURHAM, Jr., Assistant Editor ELEANOR KNOWLES, Assistant Editor FRANK McENTIRE, Assistant Editor MARTHA ELIZABETH BRADLEY, Assistant Editor JILL MULVAY DERR, Assistant Editor Board of Editors MARIO DE PILLIS (1988), University of Massachusetts PAUL M. -

MOUNTAIN FEVER in the 1847 MORMON PIONEER COMPANIES Jay A

MOUNTAIN FEVER IN THE 1847 MORMON PIONEER COMPANIES Jay A. Aldous The cause of mountain fever has been debated for two individuals were debilitated from their long period years, but this query has additional interest because of of exposure and stamation Also, the American River the sesquicentennial year of the arrival of the Mormon near Saaamento is hardly in the mountains. Other pioneers in the Salt Lake Valley. Indeed, one may ask accounts place Elizabeth's death in the Siena Nevada what effect this disease had on the 1847Mormon pioneer Mountains during her escape from the camp at Truckee companies. This paper attempts to determine to what (Dormer) Lake. Whatever the cause of illness, both of extent the disease affected the progress of the 1847 pio- these victims succumbed. neer companies and, in particular, the Brigham Young Company. Rebecca Nutting Woodson, on her way to California in 1850, wrote: "When we was coming down the moun- The term mountain fever is apparently a catch-all tain there was several of us took sick with mountain term referred to in many western histories. One histori- fever I took it before we crossed the summit of the cal writer, George Stewart, speaks of this condition as Rockies."s This case would have occurred on the east "that vague disease called 'mountain fever,' which seems side of South Pass. Tbis victim lived, but her use of the to have meant any fever you had when you were in the term mountain fever indicates she would expect the read- mountains."l Additionally, Dr. Ralph T. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 18, No. 1, 1992

Journal of Mormon History Volume 18 Issue 1 Article 1 1992 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 18, No. 1, 1992 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1992) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 18, No. 1, 1992," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 18 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol18/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 18, No. 1, 1992 Table of Contents PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS • --The Mormon-RLDS Boundary, 1852-1991: Walls to Windows Richard P. Howard, 1 • --Seniority in the Twelve: The 1875 Realignment of Orson Pratt Gary James Bergera, 19 • --The Jews, the Mormons, and the Holocaust Douglas F. Tobler, 59 • --Ultimate Taboos: Incest and Mormon Polygamy Jessie L. Embry, 93 • --The Mormon Boundary Question in the 1849-50 Statehood Debates Glen M. Leonard, 114 • --TANNER LECTURE Mormon "Deliverance" and the Closing of the Frontier Martin Ridge, 137 • --"A Kinship of Interest": The Mormon History Association's Membership Patricia Lyn Scott, James E. Crooks, and Sharon G. Pugsley, 153 This full issue is available in Journal of Mormon History: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol18/iss1/ 1 JOURNAL OF MORMON HISTORY JOURNAL OF MORMON HISTORY DESIGN by Warren Archer. Cover: Abstraction of the window tracery, Salt Lake City Seventeenth Ward. -

Zerah Pulsipher and the Utah War

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Arrington Student Writing Award Winners Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lectures 12-2014 Hero Worship and Persecution: Zerah Pulsipher and the Utah War Chad L. Nielsen Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/arrington_stwriting Recommended Citation Nielsen, Chad L., "Hero Worship and Persecution: Zerah Pulsipher and the Utah War" (2014). Arrington Student Writing Award Winners. Paper 15. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/arrington_stwriting/15 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lectures at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arrington Student Writing Award Winners by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hero Worship and Persecution: Zerah Pulsipher and the Utah War Chad L. Nielsen Utah State University Lecture Synopsis For, as I take it, Universal History, the history of what man has accomplished in this world, is at bottom the History of the Great Men who have worked here. They were the leaders of men, these great ones; the modellers, patterns, and in a wide sense creators, of whatsoever the general mass of men contrived to do or to attain; all things that we see standing accomplished in the world are properly the outer material result, the practical realization and embodiment, of Thoughts that dwelt in the Great Men sent into the world: the soul of the whole world's history, it may justly be considered, were the history of these.1 This statement, written by Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle, served as the basis of Ronald W. -

Journal of Mormon History, Volume 40, Issue 2 (2014)

Journal of Mormon History Volume 40 Issue 2 Journal of Mormon History, volume 40, Article 1 issue 2 (spring 2014) 4-1-2014 Journal of Mormon History, volume 40, issue 2 (2014) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Recommended Citation CONTENTS ARTICLES --[PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS] Seeking an Inheritance: Mormon Mobility, Urbanity, and Community, Glen M. Leonard, 1 --[TANNER LECTURE] Mormons, Freethinkers, and the Limits of Toleration, Leigh Eric Schmidt, 59 --Succession by Seniority: The Development of Procedural Precedents in the LDS Church, Edward Leo Lyman, 92 --The Bullion, Beck, and Champion Mining Company and the Redemption of Zion, R. Jean Addams, 159 Indian Placement Program Host Families: A Mission to the Lamanites, Jessie L. Embry, 235 REVIEW Matthew Kester. Remembering Iosepa: History,Place, and Religion in the American West, Brian Q. Cannon, 277 BOOK NOTICE Francis M. Gibbons. John Taylor: Mormon Philosopher: Prophet of God, 280 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History, volume 40, issue 2 (2014) Table of Contents CONTENTS ARTICLES PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS --Seeking an Inheritance: Mormon Mobility, Urbanity, and Community, Glen M. Leonard, 1 TANNER LECTURE --Mormons, Freethinkers, and the Limits of Toleration, Leigh Eric Schmidt, 59 Succession by Seniority: The Development of Procedural Precedents in the LDS Church, Edward Leo Lyman, 92 The Bullion, Beck, and Champion Mining Company and the Redemption of Zion R. -

The Beginnings of Settlement in Cache Valley

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Faculty Honor Lectures Lectures 4-24-1953 The Beginnings of Settlement in Cache Valley Joel Edward Ricks Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honor_lectures Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Ricks, Joel Edward, "The Beginnings of Settlement in Cache Valley" (1953). Faculty Honor Lectures. Paper 43. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honor_lectures/43 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Lectures at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Honor Lectures by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BEGINNINGS OF SETTLEMENT IN CACHE VALLEY by JOEL EDWARD RICKS TWELFTH ANNUAL FACULTY RESEARCH LECTURE The Beginnings of Settlement In Cache Valley by JOEL EDWARD RrCKS Professor of History THE FACULTY ASSOCIATION lITAH STATE AGRICULTURAL COLLEGE LOGAN UTAH-1953 OTHER LECTURES IN THIS SERIES THE SCIENTIST'S CONCEPT OF THE PHYSICAL WORLD by WILLARD GARDNER IRRIGATION SCIENCE: THE FOUNDATION OF PERMANENT AGRICULTURE IN ARID REGIONS by ORSON W . ISRAEL SEN NUTRITIONAL STATUS OF SOME UTAH POPULATION GROUPS by ALMEDA PERRY BROWN RANGE LAND OF AMERICA AND SOME RESEARCH ON ITS MANAGEMENT by LAURENCE A. STODDART MIRID-BUG INJURY AS A FACTOR IN DECLINING ALF ALF ASEED YIELDS by CHARLES J. SORENSON THE FUTURE OF UTAH'S AGRICULTURE by W. PRESTON THOMAS GEOLOGICAL STUDIES IN UTAH by J . STEWART WILLIAMS INSTITUTION BUILDING IN UTAH by JOSEPH A. GEDDES THE BUNT PROBLEM IN RELATION TO WINTER WHEAT BREEDING by DELMAR C. TINGEY THE DESERT SHALL BLOSSOM AS THE ROSE by D . -

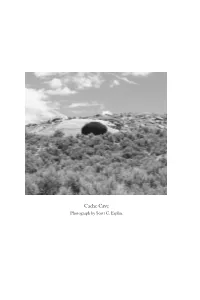

Cache Cave Photograph by Scott C

Cache Cave Photograph by Scott C. Esplin. 8 CACHE CAVE UTAH’S FIRST REGISTER Hank R. Smith n Monday, July 12, 1847, the main body of Mormon pioneers Omade their first camp in what is now known as the state of Utah. That evening, a few of the men walked a quarter mile to the east of camp to “a curious cave in the center of the [coarse] sandstone.”1 They named the cave Redden’s Cave, as Jackson Redden was the first of the company to observe it. Redden was a thirty-one-year-old former bodyguard of the Prophet Joseph Smith.2 Redden’s Cave, later known as Cache Cave, would become a notable landmark for the pioneers during the exodus from Nauvoo to the Salt Lake Valley and, a decade later, an important rendezvous point during the Utah War. One early- nineteenth-century journalist wrote that the Mormons established Cache Cave as the frontier-day church. Using it as a place for prayer, sermons, and refuge, the cave was once dubbed the “first Mormon church in the west.”3 Cache Cave should be remembered by historians Hank R. Smith is an adjunct professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University. HENRY R. SMITH and scholars as an integral piece of the Mormon Trail. From its van- tage point off to the side and above the original trail, Cache Cave stands as a stalwart witness of the courage and faith of the thousands of individuals who crossed by it with eyes fixed toward the valley of the Great Salt Lake. -

The Making of a Mormon Myth: the 1844 Transfiguration of Brigham Young*

The Making of a Mormon Myth: The 1844 Transfiguration of Brigham Young* Richard S. Van Wagoner The brethren testify that brother Brigham Young is brother Joseph's legal successor. You never heard me say so. I say that I am a good hand to keep the dogs and wolves out of the flock. —Brigham Young (I860)1 MORMONISM, AMERICA'S UNIQUE RELIGIOUS MANIFESTATION, has a remark- able past. Nourished on the spectacular, the faith can count heroic mar- tyrs, epic treks, and seemingly supernatural manifestations. Deep in the Mormon psyche is an attraction to prophetic posturing and swagger. In particular, Joseph Smith, Jr., and Brigham Young are icons who have come to dominate the Mormon world like mythical colossuses. After Smith's untimely 1844 murder, Brigham Young and an ailing Sidney Rigdon, the only surviving member of the First Presidency, be- came entangled in an ecclesiastical dogfight for primacy. Young, a mas- terful strategist with a political adroitness and physical vitality lacking in Rigdon, easily won the mantle.2 However, as time passed, the rather prosaic events surrounding this tussle for church leadership metamor- phosed into a mythical marvel. The legend is now unsurpassed in Mor- mon lore, second only to Joseph Smith's own account of angelic minis- trations and his "first vision." *This article first appeared in Vol. 28, No. 4 (Winter 1995): 1-24. 1. Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (Liverpool: LDS Bookseller's Depot, 1855-86), 8:69 (3 June 1860); hereafter JD. 2. For five years Rigdon had been weakened by episodic bouts of malaria and depres- sion. -

Introduction to the 1845-1846 Journal of Thomas Bullock

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 31 Issue 1 Article 2 1-1-1991 Introduction to the 1845-1846 Journal of Thomas Bullock Gregory R. Knight Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Knight, Gregory R. (1991) "Introduction to the 1845-1846 Journal of Thomas Bullock," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 31 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol31/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Knight: Introduction to the 1845-1846 Journal of Thomas Bullock introduction to the 1845 1846 r journal of thomas bullock gregory R knight on saturday 22 february 1845 heber C kimball laid his hands on thomas bullocks head and pronounced a blessing three days later as he was pondering on this blessing bullock poured out his soul in ajournalajoumal entry which illustrates the dreams and feelings of a man devoted to a new religious movement and its leaders oh my god prepare me for that time that I1 may according to my blessing have a glorious hope of immortal life and according to elder H C kimballsKimballs promise of last saturday that I1 may rise with the 12 and be with them thro all eternity and that I1 should always be a scribe for the 12 and that I1 should rise in the mom of the resurrection with them and be with them thro