The Effects of Leopard Predation on Grouping Patterns in Forest Chimpanzees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prowling for Predators- Africa Overnight

Prowling for Predators- Africa Overnight: SCHEDULE: 6:45- 7:00 Arrive 7:00- 8:20 Introductions Zoo Rules Itinerary Introduction to Predator/Prey dynamics- presented with live animal encounters Food Pyramid Talk 8:20- 8:45 Snack 8:45-11:00 Building Tours 11:00-11:30 HOPE Jeopardy PREPARATION: x Paint QUESTing spots with blacklight Paint x Hide clue tubes NEEDS: x Zoo Maps x Charged Blacklight Flashlights (Triple As) x Animal Food Chain Cards x Ball of String x Hula Hoops, Tablecloths ANIMAL OPTIONS: x Ball Python x Hedgehog x Tarantula x Flamingos x Hornbill x White-Faced Scops Owl x Barn Owl x Radiated Tortoise x Spiny-Tailed Lizard DEPENDING ON YOUR ORDER YOU WILL: Tour Buildings: x Commissary- QUESTing o Front: Kitchen o Back: Dry Foods x AFRICA o Front: African QUESTing- Lion o Back: African QUESTing- Cheetah x Reptile House- QUESTing o King Cobra (Right of building) Animal Demos: x In the Education Building Games: x Africa Outpost I **manageable group sizes in auditorium or classrooms x Oh Antelope x Quick Frozen Critters x HOPE Jeopardy x Africa Outpost II o HOPE Jeopardy o *Overflow game: Musk Ox Maneuvers INTRODUCTION & HIKE INFORMATION (AGE GROUP SPECIFIC) x See appendix I Prowling for Predators: Africa Outpost I Time Requirement: 4hrs. Group Size & Grades: Up to 100 people- 2nd-4t h grades Materials: QUESTing handouts Goals: -Create a sense of WONDER to all participants -We can capitalize on wonder- During up-close animal demos & in front of exhibit animals/behind the scenes opportunities. -Convey KNOWLEDGE to all participants -This should be done by using participatory teaching methods (e.g. -

Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (Genus: Pongo)- the Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2015 Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-121397 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia. Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation. 2015, University of Zurich, Faculty of Science. Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (genus: Pongo) — The Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr. sc. nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch‐naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Maja Patricia Mattle‐Greminger von Richterswil (ZH) Promotionskomitee Prof. Dr. Carel van Schaik (Vorsitz) PD Dr. Michael Krützen (Leitung der Dissertation) Dr. Maria Anisimova Zürich, 2015 To my family Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................ 1 Summary ..................................................................................................................... 3 Zusammenfassung ..................................................................................................... -

Novel Mobbing Strategies of a Fish Population Against a Sessile

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Novel mobbing strategies of a fish population against a sessile annelid predator Received: 10 December 2015 Jose Lachat & Daniel Haag-Wackernagel Accepted: 22 August 2016 When searching for food, foraging fishes expose themselves to hidden predators. The strategies that Published: 12 September 2016 maximize the survival of foraging fishes are not well understood. Here, we describe a novel type of mobbing behaviour displayed by foraging Scolopsis affinis. The fish direct sharp water jets towards the hidden sessile annelid predator Eunice aphroditois (Bobbit worm). We recognized two different behavioural roles for mobbers (i.e., initiator and subsequent participants). The first individual to exhibit behaviour indicating the discovery of the Bobbit directed, absolutely and per time unit, more water jets than the subsequent individuals that joined the mobbing. We found evidence that the mobbing impacted the behaviour of the Bobbit, e.g., by inducing retraction. S. affinis individuals either mob alone or form mobbing groups. We speculate that this behaviour may provide social benefits for its conspecifics by securing foraging territories forS. affinis. Our results reveal a sophisticated and complex behavioural strategy to protect against a hidden predator. Mobbing in the animal kingdom is described as an approach towards a potential predator followed by swoops or runs, sometimes involving a direct attack with physical contact by the mobber1. Mobbing is well characterized in birds, mammals, and even invertebrates1–5. Most of the reported mobbing behaviours initiated by a prey species involve directed harassment of a mobile predator1,3,6–9. Hidden, ambushing predators are a major threat to prey species. -

Dimensional Investment Group

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM N-Q Quarterly schedule of portfolio holdings of registered management investment company filed on Form N-Q Filing Date: 2008-04-29 | Period of Report: 2008-02-29 SEC Accession No. 0001104659-08-027772 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER DIMENSIONAL INVESTMENT GROUP INC/ Business Address 1299 OCEAN AVE CIK:861929| IRS No.: 000000000 | State of Incorp.:MD | Fiscal Year End: 1130 11TH FLOOR Type: N-Q | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-06067 | Film No.: 08784216 SANTA MONICA CA 90401 2133958005 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM N-Q QUARTERLY SCHEDULE OF PORTFOLIO HOLDINGS OF REGISTERED MANAGEMENT INVESTMENT COMPANY Investment Company Act file number 811-6067 DIMENSIONAL INVESTMENT GROUP INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in charter) 1299 Ocean Avenue, Santa Monica, CA 90401 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Catherine L. Newell, Esquire, Vice President and Secretary Dimensional Investment Group Inc., 1299 Ocean Avenue, Santa Monica, CA 90401 (Name and address of agent for service) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: 310-395-8005 Date of fiscal year end: November 30 Date of reporting period: February 29, 2008 ITEM 1. SCHEDULE OF INVESTMENTS. Dimensional Investment Group Inc. Form N-Q February 29, 2008 (Unaudited) Table of Contents Definitions of Abbreviations and Footnotes Schedules of Investments U.S. Large Cap Value Portfolio II U.S. Large Cap Value Portfolio III LWAS/DFA U.S. High Book to Market Portfolio DFA International Value Portfolio Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. -

Responses of Aquatic Non-Native Species to Novel Predator Cues and Increased Mortality

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-17-2017 Responses of Aquatic Non-Native Species to Novel Predator Cues and Increased Mortality Brian Christopher Turner Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Turner, Brian Christopher, "Responses of Aquatic Non-Native Species to Novel Predator Cues and Increased Mortality" (2017). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3620. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5512 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Responses of Aquatic Non-Native Species to Novel Predator Cues and Increased Mortality by Brian Christopher Turner A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Sciences and Resources Dissertation Committee: Catherine E. de Rivera, Chair Edwin D. Grosholz Michael T. Murphy Greg M. Ruiz Ian R. Waite Portland State University 2017 Abstract Lethal biotic interactions strongly influence the potential for aquatic non-native species to establish and endure in habitats to which they are introduced. Predators in the recipient area, including native and previously established non-native predators, can prevent establishment, limit habitat use, and reduce abundance of non-native species. Management efforts by humans using methods designed to cause mass mortality (e.g., trapping, biocide applications) can reduce or eradicate non-native populations. -

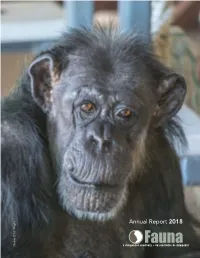

Annual Report 2018 Blackie © NJ Wight Help Us Secure Their Future

Annual Report 2018 Blackie © NJ Wight Help Us Secure Their Future HelpLIFETIME CAREUs FUND Secure Their Future Established in 2007, the Fauna Lifetime Care Fund is our promise to the Fauna chimpanzees for a lifetime of the quality care they so deserve. MONTHLY DONATION Please email us at [email protected] to set up this form of monthly giving via cheque or credit card. ONLINE • CanadaHelps.org, enter the searchtype, charity name: Fauna Foundation and it will take you directly to the link. • FaunaFoundation.org, donate via PayPal PHONE 450-658-1844 FAX 450-658-2202 MAIL Fauna Foundation 3802 Bellerive Carignan,QC J3L 3P9 They need our help—not just today but tomorrow too. Toby © Jo-Anne McArthur Toby Help me keep my promise to them. Your donation today in whatever amount you can afford means so much! Billing Information Payment Information Name: ________________________________________________ o $100 o $75 o $50 o $25 o Other $ ______ Address: ______________________________________________ o Check enclosed (payable to Fauna) City: ___________________Province/State: _________________ o Visa o Mastercard Postal Code/Zip Code:__________________________________ o o Tel: (____)_____________________________________________ Monthly pledge $ ______ Lifetime Care Fund $ ______ Email: ________________________________________________ Card Number: ______________________________________ In o honor of or in o memory of ___________________________ Exp: ___/___/___ Signature: __________________________ Or give online at www.faunafoundation.org -

Vocal Behavior Is Correlated with Mixed-Species’ Reactions to Novel Objects

University of Tennessee, Knoxville Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2015 Mixed-species Flock Members’ Reactions to Novel and Predator Stimuli Sheri Ann Browning University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Recommended Citation Browning, Sheri Ann, "Mixed-species Flock Members’ Reactions to Novel and Predator Stimuli. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3327 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Sheri Ann Browning entitled "Mixed-species Flock Members’ Reactions to Novel and Predator Stimuli." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Psychology. Todd M. Freeberg, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Gordon M. Burghardt, Matthew Cooper, David A. Buehler, Kathryn E. Sieving Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official student records.) Mixed-species Flock Members’ Reactions to Novel and Predator Stimuli A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Sheri Ann Browning May 2015 i Copyright © 2015 by Sheri Ann Browning All rights reserved. -

124214015 Full.Pdf

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI DEFENSE MECHANISM ADOPTED BY THE PROTAGONISTS AGAINST THE TERROR OF DEATH IN K.A APPLEGATE’S ANIMORPHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By MIKAEL ARI WIBISONO Student Number: 124214015 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2016 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI DEFENSE MECHANISM ADOPTED BY THE PROTAGONISTS AGAINST THE TERROR OF DEATH IN K.A APPLEGATE’S ANIMORPHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By MIKAEL ARI WIBISONO Student Number: 124214015 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2016 ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI A SarjanaSastra Undergraduate Thesis DEFENSE MECIIAMSM ADOPTED BY TITE AGAINST PROTAGOMSTS THE TERROR OT OTATTT IN K.A APPLEGATE'S AAUMORPHS By Mikael Ari Wibisono Student Number: lz4ll4}ls Defended before the Board of Examiners On August 25,2A16 and Declared Acceptable BOARD OF EXAMINERS Name Chairperson Dr. F.X. Siswadi, M.A. Secretary Dra. Sri Mulyani, M.A., ph.D / Member I Dr. F.X. Siswadi, M.A. Member2 Drs. HirmawanW[ianarkq M.Hum. Member 3 Elisa DwiWardani, S.S., M.Hum Yogyakarta, August 31 z}rc Faculty of Letters fr'.arrr s41 Dharma University s" -_# 1,ffi QG*l(tls srst*\. \ tQrtnR<{l -

Martin Pj Edwardes an Anthropological Perspective

The Origins of Self explores the role that selfhood plays in defining human society, and each human individual in that society. It considers the genetic and cultural origins of self, the role that self plays in socialisation and language, and the types of self we generate in our individual journeys to and through adulthood. Edwardes argues that other awareness is a relatively early evolutionary development, present throughout the primate clade and perhaps beyond, but self-awareness is a product of the sharing of social models, something only humans appear to do. The self of which we are aware is not something innate within us, it is a model of our self produced as a response to the models of us offered to us by other people. Edwardes proposes that human construction of selfhood involves seven different types of self. All but one of them are internally generated models, and the only non-model, the actual self, is completely hidden from conscious awareness. We rely on others to tell us about our self, and even to let us know we are a self. Developed in relation to a range of subject areas – linguistics, anthropology, genomics and cognition, as well as socio-cultural theory – The Origins of Self is of particular interest to MARTIN P. J. EDWARDES students and researchers studying the origins of language, human origins in general, and the cognitive differences between human and other animal psychologies. Martin P. J. Edwardes is a visiting lecturer at King’s College London. He is currently teaching modules on Language Origins and Language Construction. -

Transitions: Fall 2016 Mcgill & the World

TRANSITIONS: 2016 FALL MCGILL & THE WORLD A PUBLICATION OF THE The BULL & BEAR EDITOR’S NOTE CONTENTS Jennifer Yoon Executive Editor FEATURE 4 Holding McGill Accountable 5 Humanities Under Attack 7 Two-Sides of a Coin: The Smoking Ban Shifting sands have never felt more unsettling. NEWS That’s only half a simile. The giant holes tearing up our campus streets are 8 Profile of Trump literally scrambling the soil beneath our feet. Apparently, our helmeted Supporters on Campus brigade of construction workers will be around for at least a few more years. What exactly are they working on again? Nobody knows. 10Indigenous Awareness Week Students are hurting from the myriad of changes, too. We’ve seen protests against austerity measures and for student workers’ rights. With classes BUSINESS & TECH and extracurriculars curtailed, students unsurprisingly take to the streets 11 Make Polling Great Again in protest – fulfilling a longstanding tradition amongst les étudiants 12 The Future of Food Montréalais. 14 Emergence of a Cashless Society And then, of course, there is the political fiasco South of the border. The election brought out the ugly in American society, terrifying women, racial minorities, LGBTQ folks, and more. Others began to seriously question ARTS & CULTURE the inherent value of previously revered democratic institutions: the 17 Crying in the Club with fourth estate, pluralism, and even foundational electoral processes. Venus 19 Skirting the Issues For many of us, 2016 has been a momentous year: in the course of these 21 Obituary: Public Libraries months, we’ve become accustomed a permanent state of uncertainty. (300 BC-2016 AD) 23 I Spend Way Too Much In this issue, we have tried to unpack some aspects of our increasingly unpredictable world – both on-campus, and off-campus. -

2012 EWDA Conference Program and Abstract Book.Pdf

Contents Welcome Address 5 Conference Program 7 Abstracts Oral Presentations 15 One Health Session 17 Population Health Assessment Session 34 Migration Session 48 WDA Student Research Recognition Award 51 Terry Amundson Award Student Session 52 Disease Control Session 72 Pathogenesis Session 79 Pathogen Discovery and Disease Emergence Session 86 Translocation and Reintroduction Session 89 Multiple Pollutants 92 Poster Presentations 93 Poster Session 1 95 Poster Session 2 217 Poster Session 3 325 Workshops 427 WDA EWDA 2012 Conference Scientific Committee 429 WDA EWDA 2012 Conference Organizing Committee 429 WDA 2012 Officers and Council 430 EWDA 2010/2012 Officers and Board 430 Index of Presenting Authors 433 WDA EWDA 2012: Site of Interest Map 437 Conference Overview 3 4 Welcome Address Dr. Bernard VALLAT, Directeur général de l'Organisation Mondiale de la Santé Animale (OIE), 12 rue de Prony, 75017 Paris The OIE welcomes participants to the “Convergence in wildlife health” Conference and is pleased to have been a partner for this successful event, alongside VetAgro Sup, the WDA and the EWDA. Movements of animals and people enable pathogens to travel faster than the incubation period of the epizootic diseases they cause and the health risks for humans, domestic animals and wildlife are rapidly evolving. Growth of the human population, climate change and increased land use are all factors that must be urgently taken into account to safeguard biodiversity on all continents. The Veterinary Services and veterinary teaching establishments must strengthen their capacities in the field of wildlife conservation and health management. New tools and new forms of collaboration and synergies need to be established between these services, wildlife specialists and users of the natural environment, which will in future provide valuable assistance in this field . -

Territory Characteristics Among Three Neighboring Chimpanzee Communities in the Taı¨ National Park, Coteˆ D’Ivoire

P1: FJT International Journal of Primatology [ijop] PP046-293191 March 9, 2001 10:45 Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999 International Journal of Primatology, Vol. 22, No. 2, 2001 Territory Characteristics among Three Neighboring Chimpanzee Communities in the Taı¨ National Park, Coteˆ d’Ivoire Ilka Herbinger,1,3 Christophe Boesch,1 and Hartmut Rothe2 Received May 11, 1999; revised February 7, 2000; accepted February 24, 2000 We studied territory characteristics among three neighboring chimpanzee communities in the Ta¨ı National Park, Coteˆ d’Ivoire, and compared them with other chimpanzee populations. We characterized territories and rang- ing patterns by analyzing six variables: (1) territory size, (2) overlap zone, (3) territory utilization, (4) core area, (5) territory shift, and (6) travel dis- tance. Data collection covered a period of 10 mo, during which we simultane- ously sampled the local positions of mostly large parties, including males in each community, in 30-min intervals. In Ta¨ı, chimpanzees used territories in a clumped way, with small central core areas being used preferentially over large peripheral areas. Although overlap zones between study communities mainly represented infrequently visited peripheral areas, overlap zones with all neighboring communities also included intensively used central areas. Ter- ritory utilization was not strongly seasonal, with no major shift of activity center or shift of areas used over consecutive months. However, we observed shorter daily travel distances in times of low food availability. Territory sizes of Ta¨ı chimpanzees tended to be larger than territories in other chimpanzee communities, presumably because high food availability allows for econom- ical defense of territorial borders and time investment in territorial activities.