Martin Pj Edwardes an Anthropological Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes for Chapter Re-Drafts

Making Markets for Japanese Cinema: A Study of Distribution Practices for Japanese Films on DVD in the UK from 2008 to 2010 Jonathan Wroot PhD Thesis Submitted to the University of East Anglia For the qualification of PhD in Film Studies 2013 1 Making Markets for Japanese Cinema: A Study of Distribution Practices for Japanese Films on DVD in the UK from 2008 to 2010 2 Acknowledgements Thanks needed to be expressed to a number of people over the last three years – and I apologise if I forget anyone here. First of all, thank you to Rayna Denison and Keith Johnston for agreeing to oversee this research – which required reining in my enthusiasm as much as attempting to tease it out of me and turn it into coherent writing. Thanks to Mark Jancovich, who helped me get started with the PhD at UEA. A big thank you also to Andrew Kirkham and Adam Torel for doing what they do at 4Digital Asia, Third Window, and their other ventures – if they did not do it, this thesis would not exist. Also, a big thank you to my numerous other friends and family – whose support was invaluable, despite the distance between most of them and Norwich. And finally, the biggest thank you of all goes to Christina, for constantly being there with her support and encouragement. 3 Abstract The thesis will examine how DVD distribution can affect Japanese film dissemination in the UK. The media discourse concerning 4Digital Asia and Third Window proposes that this is the principal factor influencing their films’ presence in the UK from 2008 to 2010. -

Altriciality and the Evolution of Toe Orientation in Birds

Evol Biol DOI 10.1007/s11692-015-9334-7 SYNTHESIS PAPER Altriciality and the Evolution of Toe Orientation in Birds 1 1 1 Joa˜o Francisco Botelho • Daniel Smith-Paredes • Alexander O. Vargas Received: 3 November 2014 / Accepted: 18 June 2015 Ó Springer Science+Business Media New York 2015 Abstract Specialized morphologies of bird feet have trees, to swim under and above the water surface, to hunt and evolved several times independently as different groups have fish, and to walk in the mud and over aquatic vegetation, become zygodactyl, semi-zygodactyl, heterodactyl, pam- among other abilities. Toe orientations in the foot can be prodactyl or syndactyl. Birds have also convergently described in six main types: Anisodactyl feet have digit II evolved similar modes of development, in a spectrum that (dII), digit III (dIII) and digit IV (dIV) pointing forward and goes from precocial to altricial. Using the new context pro- digit I (dI) pointing backward. From the basal anisodactyl vided by recent molecular phylogenies, we compared the condition four feet types have arisen by modifications in the evolution of foot morphology and modes of development orientation of digits. Zygodactyl feet have dI and dIV ori- among extant avian families. Variations in the arrangement ented backward and dII and dIII oriented forward, a condi- of toes with respect to the anisodactyl ancestral condition tion similar to heterodactyl feet, which have dI and dII have occurred only in altricial groups. Those groups repre- oriented backward and dIII and dIV oriented forward. Semi- sent four independent events of super-altriciality and many zygodactyl birds can assume a facultative zygodactyl or independent transformations of toe arrangements (at least almost zygodactyl orientation. -

Predictors of Juvenile Survival in Birds

Ornithological Monographs Volume (2013), No. 78, 1–55 © The American Ornithologists’ Union, 2013. Printed in USA. PREDICTORS OF JUVENILE SURVIVAL IN BIRDS TERRI J. MANESS1,2,3 AND DAVID J. ANDERSON2 1School of Biological Sciences, Louisiana Tech University, Ruston, Louisiana 71272, USA; and 2Department of Biology, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27106, USA ABSTRACT.—The survival probability of birds during the juvenile period, between the end of parental care and adulthood, is highly variable and has a major effect on population dynamics and parental fitness. As such, a large number of studies have attempted to evaluate potential predictors of juvenile survival in birds, especially predictors related to parental care. Lack’s hypothesis linking body reserves accumulated from parental care to the survival of naive juveniles has organized much of this research, but various other predictors have also been investigated and received some support. We reviewed the literature in this area and identified a variety of methodological problems that obscure interpretation of the body of results. Most studies adopted statistical techniques that missed the opportunities to (1) evaluate the relative importance of several predictors, (2) control the confounding effect of correlation among predictor variables, and (3) exploit the information content of collinearity by evaluating indirect (via correlation) as well as direct effects of potential predictors on juvenile survival. Ultimately, we concluded that too few reliable studies exist to allow robust evaluations of any hypothesis regarding juvenile survival in birds. We used path analysis to test potential predictors of juvenile survival of 2,631 offspring from seven annual cohorts of a seabird, the Nazca Booby (Sula granti). -

Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (Genus: Pongo)- the Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2015 Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-121397 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia. Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation. 2015, University of Zurich, Faculty of Science. Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (genus: Pongo) — The Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr. sc. nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch‐naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Maja Patricia Mattle‐Greminger von Richterswil (ZH) Promotionskomitee Prof. Dr. Carel van Schaik (Vorsitz) PD Dr. Michael Krützen (Leitung der Dissertation) Dr. Maria Anisimova Zürich, 2015 To my family Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................ 1 Summary ..................................................................................................................... 3 Zusammenfassung ..................................................................................................... -

Blues from Chicken Shack CHICKEN SHACK Tears in the Wind; the Things You Put Me Through (Cbsblue Horizon 3160)

RECORD MIRROR, Week ending August 23, 1969 9 reviewed by peter Jones new singles reviewed by Peter Jones new singles reviewed by Peter Jo Moody and compulsive DJ blues from Chicken Shack CHICKEN SHACK Tears In The Wind; The Things You Put Me Through (CBSBlue Horizon 3160). Firstfromthe team since Christine Perfect left- after a moodily-relaxed opening, they get a somehow heavier sound than before.Stan Webb, who wrote MARK JASON 12 thetopdeck,handlesvocallead Love Is The Name Of The Game: well but a big emphasis in on new For The First Time In My Life man Paul Raymond's piano power. (Fontana TF 1050).A Ken Howard this week-dave symonds Thisiscompulsive listening,build- and Alan Blaikley song, which Isn't ingwell and emphatically bluesY- a bad kick-offforahighly -touted A hit, Flip:Notavailableat new singer.Actually Mark is well This week we have David Symonds as the guest disc Presstime. above average in style and person- CHART CERTAINTY. ality and thisisa punchy, brisk, jockey. David ofthedeepvoiceand bearded business -likesort ofproductionall countenance, plus being a sportsman extraordinaire. round. Couldmissout,butit's As usual the selection is six of the best of the oldies, SPANISH musicwiththeusual commendedanddeservestoget through. Flip: A slower -moving six favourites of the current crop and also the all time flair and fire:"Maria Isabel", romantic ballad. favourite LP. by LOS PAYOS (Ilispa Vox 307). CHART POSSIBILITY Frontthe FRANCO-LONDON OR- David, who has very definite tastes in music, started CHESTRA: "MainTheme Front BRIAN KEITH Robinson Crusoe" off with "Alone Again Or" by Love. "I've picked this (Philips BF Till We Meet Again; Lady Butter- 1806), musicfromthetelevision because I thinkit'sa very pretty number," he said. -

Dimensional Investment Group

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM N-Q Quarterly schedule of portfolio holdings of registered management investment company filed on Form N-Q Filing Date: 2008-04-29 | Period of Report: 2008-02-29 SEC Accession No. 0001104659-08-027772 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER DIMENSIONAL INVESTMENT GROUP INC/ Business Address 1299 OCEAN AVE CIK:861929| IRS No.: 000000000 | State of Incorp.:MD | Fiscal Year End: 1130 11TH FLOOR Type: N-Q | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-06067 | Film No.: 08784216 SANTA MONICA CA 90401 2133958005 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM N-Q QUARTERLY SCHEDULE OF PORTFOLIO HOLDINGS OF REGISTERED MANAGEMENT INVESTMENT COMPANY Investment Company Act file number 811-6067 DIMENSIONAL INVESTMENT GROUP INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in charter) 1299 Ocean Avenue, Santa Monica, CA 90401 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Catherine L. Newell, Esquire, Vice President and Secretary Dimensional Investment Group Inc., 1299 Ocean Avenue, Santa Monica, CA 90401 (Name and address of agent for service) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: 310-395-8005 Date of fiscal year end: November 30 Date of reporting period: February 29, 2008 ITEM 1. SCHEDULE OF INVESTMENTS. Dimensional Investment Group Inc. Form N-Q February 29, 2008 (Unaudited) Table of Contents Definitions of Abbreviations and Footnotes Schedules of Investments U.S. Large Cap Value Portfolio II U.S. Large Cap Value Portfolio III LWAS/DFA U.S. High Book to Market Portfolio DFA International Value Portfolio Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. -

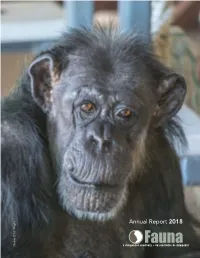

Annual Report 2018 Blackie © NJ Wight Help Us Secure Their Future

Annual Report 2018 Blackie © NJ Wight Help Us Secure Their Future HelpLIFETIME CAREUs FUND Secure Their Future Established in 2007, the Fauna Lifetime Care Fund is our promise to the Fauna chimpanzees for a lifetime of the quality care they so deserve. MONTHLY DONATION Please email us at [email protected] to set up this form of monthly giving via cheque or credit card. ONLINE • CanadaHelps.org, enter the searchtype, charity name: Fauna Foundation and it will take you directly to the link. • FaunaFoundation.org, donate via PayPal PHONE 450-658-1844 FAX 450-658-2202 MAIL Fauna Foundation 3802 Bellerive Carignan,QC J3L 3P9 They need our help—not just today but tomorrow too. Toby © Jo-Anne McArthur Toby Help me keep my promise to them. Your donation today in whatever amount you can afford means so much! Billing Information Payment Information Name: ________________________________________________ o $100 o $75 o $50 o $25 o Other $ ______ Address: ______________________________________________ o Check enclosed (payable to Fauna) City: ___________________Province/State: _________________ o Visa o Mastercard Postal Code/Zip Code:__________________________________ o o Tel: (____)_____________________________________________ Monthly pledge $ ______ Lifetime Care Fund $ ______ Email: ________________________________________________ Card Number: ______________________________________ In o honor of or in o memory of ___________________________ Exp: ___/___/___ Signature: __________________________ Or give online at www.faunafoundation.org -

The Example of the United Red Army in the Manga Red (2006–2018)

IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 6 – Issue 1 – Summer 2019 Memory Politics and Popular Culture – The Example of the United Red Army in the Manga Red (2006–2018) Fabien Carpentras, Yokohama National University, Japan Abstract Serialized in a period of booming popular interest for the United Red Army (URA), Red (2006– 2018) by manga artist Yamamoto Naoki (1960–) is to this day the most thoroughly detailed and researched work of fiction drawing on the famous Japanese terrorist group. In the present article, we would like to address how Yamamoto is fully engaged in a memory struggle regarding the “truth” of the historical event – he has been active in the “Association to transmit the overall picture of the United Red Army incident,” a group involved in the gathering and publishing of testimonies surrounding the incident, bringing to the fore until then unknown and neglected details of the URA. And yet, serialized in the seinen manga magazine Evening, Red constitutes at the same time a genuine piece of popular culture, fostering narrative and visual devices aimed at a large audience (for instance, all the characters appear with false and dramatized names – Nagata Hiroko becoming Akagi or “Red Castle” Hiroko – and the ideological motivations are all downplayed in favor of more sanitized and universal ones). By so doing, Yamamoto succeeds in reshaping the popular memory of the URA, but we argue that this reworking is made at the expense of the political and social background of the organization, with the result of hindering our social and historical understanding of this foundational event of contemporary Japan politics. -

The Platypus Is Not a Rodent: DNA Hybridization, Amniote Phylogeny and the Palimpsest Theory

The platypus is not a rodent: DNA hybridization, amniote phylogeny and the palimpsest theory John A. W. Kirsch1* and Gregory C. Mayer1,2 1The University of Wisconsin Zoological Museum, 250 North Mills Street, Madison,WI 53706, USA 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Parkside, Kenosha,WI 53141, USA We present DNA-hybridization data on 21 amniotes and two anurans showing that discrimination is obtained among most of these at the class and lower levels. Trees generated from these data largely agree with conventional views, for example in not associating birds and mammals. However, the sister relation- ships found here of the monotremes to marsupials, and of turtles to the alligator, are surprising results which are nonetheless consistent with the results of some other studies. The Marsupionta hypothesis of Gregory is reviewed, as are opinions about the placement of chelonians. Anatomical and reproductive data considered by Gregory do not unequivocally preclude a marsupial^monotreme special relationship, and there is other recent evidence for placing turtles within the Diapsida. We conclude that the evidential meaning of the molecular data is as shown in the trees, but that the topologies may be in£uenced by a base- compositional bias producing a seemingly slow evolutionary rate in monotremes, or by algorithmic artefacts (in the case of turtles as well). Keywords: Chelonia; Crocodilia; Eutheria; Marsupialia; Marsupionta; molecular evolution `Unyielding factualists have so set the style in taxonomy relationships continue to be debated, `everyone knows' and morphology that, if their assertions were accepted, that the latter result cannot be correct. hardly any known type of animal could possibly have The orthodox view of the phylogeny of mammals been derived even from any known past group.' regards monotremes (the living `Prototheria') as the Gregory (1947, p. -

ALBUMS EAG -ES, "HOTEL CALIFORNIA" (Prod

DFDICATED TO THE NF SINGLES ALBUMS EAG -ES, "HOTEL CALIFORNIA" (prod. by Bill SPINNERS; "YOU'RE THROWING A GOOD LOVE AMERICA, "HARBOR." This trio has Szymczyk) (writers: Felder -Henley - AWAY" (prod. by Thom Bell) (writ- mastered a form-easy-going, soft rock Frey) (pub. not listed) (6:08). Prob- ers: S. Marshall & T. Wortham) built around three-part harmonies and ably America's hottest group on bath (Mighty Three, BMI) (3:36). The group (on its more recent Ips) the sweet pro- the album and singles levels, The has slowed the tempo from its romp- duction and arrangements of George Eagles have followed the stunning ing "Rubberband Man" but main- Martin. "Don't Cry Baby," -Now She's success of "New Kid In Town" with tains the eclectic sound that has Gone" and "Sergeant Darkness" fill the the title track from their platinum made them a major force through- prescription most eloquently. They'll Ip. A mild reggae flavor pervades out pop and souldom. The track is never be in dry dock. Warner Bros. BSK the tune. Asylum 45386. from their forthcoming Ip. Atl. 3382. 3017 (7.98). THE MANHATTANS, "IT FEELS SO GOOD TO THE ISLEY BROTHERS, "THE PRIDE" (prod. by BAC -ëMAN-TURNER OVERDRIVE, "FREE- ItF LOVED SO BAD' (prod. by The The Isley Brothers) (R. Isley-O. Isley- WAYS." With "Freeways," BTO has Manhattans Co./Bobby Martin) (Raze R. Isley-C. Jasper -E.. Isley-M.Isley) reached a new stage of its career. zle Dazzle, BMI) (3:58). The group (Bovina, ASCAP) (3:25). A growling Hinted at previously _but fully devel- opens the tune with one of its by guitar and loping bass sound sets oped now, the group has retained its now obligatory narrative exhorta- the pace for the group's best effort power while moving to a more melody tions which sets the tors. -

Mammalian Organogenesis in Deep Time: Tools for Teaching and Outreach Marcelo R

Sánchez‑Villagra and Werneburg Evo Edu Outreach (2016) 9:11 DOI 10.1186/s12052-016-0062-y REVIEW Open Access Mammalian organogenesis in deep time: tools for teaching and outreach Marcelo R. Sánchez‑Villagra1 and Ingmar Werneburg1,2,3,4* Abstract Mammals constitute a rich subject of study on evolution and development and provide model organisms for experi‑ mental investigations. They can serve to illustrate how ontogeny and phylogeny can be studied together and how the reconstruction of ancestors of our own evolutionary lineage can be approached. Likewise, mammals can be used to promote ’tree thinking’ and can provide an organismal appreciation of evolutionary changes. This subject is suitable for the classroom and to the public at large given the interest and familiarity of people with mammals and their closest relatives. We present a simple exercise in which embryonic development is presented as a transforma‑ tive process that can be observed, compared, and analyzed. In addition, we provide and discuss a freely available animation on organogenesis and life history evolution in mammals. An evolutionary tree can be the best tool to order and understand those transformations for different species. A simple exercise introduces the subject of changes in developmental timing or heterochrony and its importance in evolution. The developmental perspective is relevant in teaching and outreach efforts for the understanding of evolutionary theory today. Keywords: Development, Ontogeny, Embryology, Phylogeny, Heterochrony, Recapitulation, Placentalia, Human Background (Gilbert 2013), followed by the growth process. In pla- Mammals are a diverse group in which to examine devel- cental mammals, organogenesis takes place mostly in the opment and evolution, and besides the mouse and the rat uterus, whereas in monotremes and marsupials a very used in biomedical research, provide subjects based on immature hatchling or newborn, respectively, develops which experimental (Harjunmaa et al. -

Black Sabbath the Complete Guide

Black Sabbath The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 17 May 2010 12:17:46 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Black Sabbath 1 The members 23 List of Black Sabbath band members 23 Vinny Appice 29 Don Arden 32 Bev Bevan 37 Mike Bordin 39 Jo Burt 43 Geezer Butler 44 Terry Chimes 47 Gordon Copley 49 Bob Daisley 50 Ronnie James Dio 54 Jeff Fenholt 59 Ian Gillan 62 Ray Gillen 70 Glenn Hughes 72 Tony Iommi 78 Tony Martin 87 Neil Murray 90 Geoff Nicholls 97 Ozzy Osbourne 99 Cozy Powell 111 Bobby Rondinelli 118 Eric Singer 120 Dave Spitz 124 Adam Wakeman 125 Dave Walker 127 Bill Ward 132 Related bands 135 Heaven & Hell 135 Mythology 140 Discography 141 Black Sabbath discography 141 Studio albums 149 Black Sabbath 149 Paranoid 153 Master of Reality 157 Black Sabbath Vol. 4 162 Sabbath Bloody Sabbath 167 Sabotage 171 Technical Ecstasy 175 Never Say Die! 178 Heaven and Hell 181 Mob Rules 186 Born Again 190 Seventh Star 194 The Eternal Idol 197 Headless Cross 200 Tyr 203 Dehumanizer 206 Cross Purposes 210 Forbidden 212 Live Albums 214 Live Evil 214 Cross Purposes Live 218 Reunion 220 Past Lives 223 Live at Hammersmith Odeon 225 Compilations and re-releases 227 We Sold Our Soul for Rock 'n' Roll 227 The Sabbath Stones 230 Symptom of the Universe: The Original Black Sabbath 1970–1978 232 Black Box: The Complete Original Black Sabbath 235 Greatest Hits 1970–1978 237 Black Sabbath: The Dio Years 239 The Rules of Hell 243 Other related albums 245 Live at Last 245 The Sabbath Collection 247 The Ozzy Osbourne Years 249 Nativity in Black 251 Under Wheels of Confusion 254 In These Black Days 256 The Best of Black Sabbath 258 Club Sonderauflage 262 Songs 263 Black Sabbath 263 Changes 265 Children of the Grave 267 Die Young 270 Dirty Women 272 Disturbing the Priest 273 Electric Funeral 274 Evil Woman 275 Fairies Wear Boots 276 Hand of Doom 277 Heaven and Hell 278 Into the Void 280 Iron Man 282 The Mob Rules 284 N.