Human Rights As Politics.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (Genus: Pongo)- the Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2015 Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-121397 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia. Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation. 2015, University of Zurich, Faculty of Science. Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (genus: Pongo) — The Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr. sc. nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch‐naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Maja Patricia Mattle‐Greminger von Richterswil (ZH) Promotionskomitee Prof. Dr. Carel van Schaik (Vorsitz) PD Dr. Michael Krützen (Leitung der Dissertation) Dr. Maria Anisimova Zürich, 2015 To my family Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................ 1 Summary ..................................................................................................................... 3 Zusammenfassung ..................................................................................................... -

Socio-Economic Factors Influencing Kenya-China Relations

i SOCIO-ECONOMIC FACTORS INFLUENCING KENYA-CHINA RELATIONS BY FAIMA MOHAMMED A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES, DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY, POLITICAL SCIENCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION IN PARTIAL FULLFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN DIPLOMACY AND FOREIGN POLICY (EXECUTIVE) MOI UNIVERSITY 2020 ii DECLARATION Declaration by Candidate This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other university. No part of this project may be reproduced without prior permission of the author and/or Moi University. Signature: _________________________ Date: ____________________ FAIMA MOHAMMED SASS/PGDFP/001/18 Declaration by the Supervisors This thesis has been submitted for examination with our approval as University supervisors. Signature: _________________________ Date: ____________________ Mr. WENANI A. KILONGI Department of History, Political Science and Public Administration Moi University, Eldoret Signature: _________________________ Date: ____________________ Dr Paul K. Kurgat Department of History, Political Science and Public Administration Moi University, Eldoret iii DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my mum Duthi Hassan and beloved husband Faisal Mohammed for their undying support and consideration. To Rahma, Yasmin and Faiza for their encouragement and to Faaiz and Mahmoud for always being an inspiration. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This work would not have been possible were it not for the Almighty God. Secondly, I sincerely thank my supervisors; Mr Wenani Kilongi and Dr Paul Kurgat. I immensely benefitted from their constructive intellectual criticism and guidance. They went out of their way to read and give suggestions that improved this work a great deal. Special gratitude goes to my informants who made this research a success by willingly giving me the information needed in various interviews. -

Dimensional Investment Group

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM N-Q Quarterly schedule of portfolio holdings of registered management investment company filed on Form N-Q Filing Date: 2008-04-29 | Period of Report: 2008-02-29 SEC Accession No. 0001104659-08-027772 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER DIMENSIONAL INVESTMENT GROUP INC/ Business Address 1299 OCEAN AVE CIK:861929| IRS No.: 000000000 | State of Incorp.:MD | Fiscal Year End: 1130 11TH FLOOR Type: N-Q | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-06067 | Film No.: 08784216 SANTA MONICA CA 90401 2133958005 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM N-Q QUARTERLY SCHEDULE OF PORTFOLIO HOLDINGS OF REGISTERED MANAGEMENT INVESTMENT COMPANY Investment Company Act file number 811-6067 DIMENSIONAL INVESTMENT GROUP INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in charter) 1299 Ocean Avenue, Santa Monica, CA 90401 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Catherine L. Newell, Esquire, Vice President and Secretary Dimensional Investment Group Inc., 1299 Ocean Avenue, Santa Monica, CA 90401 (Name and address of agent for service) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: 310-395-8005 Date of fiscal year end: November 30 Date of reporting period: February 29, 2008 ITEM 1. SCHEDULE OF INVESTMENTS. Dimensional Investment Group Inc. Form N-Q February 29, 2008 (Unaudited) Table of Contents Definitions of Abbreviations and Footnotes Schedules of Investments U.S. Large Cap Value Portfolio II U.S. Large Cap Value Portfolio III LWAS/DFA U.S. High Book to Market Portfolio DFA International Value Portfolio Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. -

The Kenya General Election

AAFFRRIICCAA NNOOTTEESS Number 14 January 2003 The Kenya General Election: senior ministerial positions from 1963 to 1991; new Minister December 27, 2002 of Education George Saitoti and Foreign Minister Kalonzo Musyoka are also experienced hands; and the new David Throup administration includes several able technocrats who have held “shadow ministerial positions.” The new government will be The Kenya African National Union (KANU), which has ruled more self-confident and less suspicious of the United States Kenya since independence in December 1963, suffered a than was the Moi regime. Several members know the United disastrous defeat in the country’s general election on December States well, and most of them recognize the crucial role that it 27, 2002, winning less than one-third of the seats in the new has played in sustaining both opposition political parties and National Assembly. The National Alliance Rainbow Coalition Kenyan civil society over the last decade. (NARC), which brought together the former ethnically based opposition parties with dissidents from KANU only in The new Kibaki government will be as reliable an ally of the October, emerged with a secure overall majority, winning no United States in the war against terrorism as President Moi’s, fewer than 126 seats, while the former ruling party won only and a more active and constructive partner in NEPAD and 63. Mwai Kibaki, leader of the Democratic Party (DP) and of bilateral economic discussions. It will continue the former the NARC opposition coalition, was sworn in as Kenya’s third government’s valuable mediating role in the Sudanese peace president on December 30. -

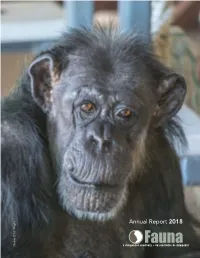

Annual Report 2018 Blackie © NJ Wight Help Us Secure Their Future

Annual Report 2018 Blackie © NJ Wight Help Us Secure Their Future HelpLIFETIME CAREUs FUND Secure Their Future Established in 2007, the Fauna Lifetime Care Fund is our promise to the Fauna chimpanzees for a lifetime of the quality care they so deserve. MONTHLY DONATION Please email us at [email protected] to set up this form of monthly giving via cheque or credit card. ONLINE • CanadaHelps.org, enter the searchtype, charity name: Fauna Foundation and it will take you directly to the link. • FaunaFoundation.org, donate via PayPal PHONE 450-658-1844 FAX 450-658-2202 MAIL Fauna Foundation 3802 Bellerive Carignan,QC J3L 3P9 They need our help—not just today but tomorrow too. Toby © Jo-Anne McArthur Toby Help me keep my promise to them. Your donation today in whatever amount you can afford means so much! Billing Information Payment Information Name: ________________________________________________ o $100 o $75 o $50 o $25 o Other $ ______ Address: ______________________________________________ o Check enclosed (payable to Fauna) City: ___________________Province/State: _________________ o Visa o Mastercard Postal Code/Zip Code:__________________________________ o o Tel: (____)_____________________________________________ Monthly pledge $ ______ Lifetime Care Fund $ ______ Email: ________________________________________________ Card Number: ______________________________________ In o honor of or in o memory of ___________________________ Exp: ___/___/___ Signature: __________________________ Or give online at www.faunafoundation.org -

Republic of Kenya Ministry of Foreign Affairs And

REPUBLIC OF KENYA MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE STRATEGIC PLAN 2018/19 – 2022/23 APRIL 2018 i Foreword The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Trade is mandated to pursue Kenya’s Foreign Policy in accordance with the Constitution of Kenya, with the overarching objective of projecting, promoting and protecting the nation’s interests abroad. Kenya’s Foreign Policy is a tool for pursuing, projecting, promoting and protecting national interests and values across the globe. The underpinning principle of the policy is a strong advocacy for a rule-based international system, environmental sustainability, equitable development and a secure world. This desire and commitment is aptly captured in our vision statement, “A peaceful, prosperous, and globally competitive Kenya” and the mission statement: “To project, promote and protect Kenya’s interests and image globally through innovative diplomacy, and contribute towards a just, peaceful and equitable world”. The overarching goal of this Strategic Plan is to contribute to the country’s development agenda and aspirations under the Kenya Vision 2030, the Third Medium Term Plan and the “Big Four” Agenda on: manufacturing, food and nutrition security, affordable healthcare and affordable housing for Kenyans. We are operating in a period of rapid transition in international relations as exemplified in the unprecedented political and socio-economic dynamism within the global system. A robust and dynamic foreign policy grounded on empirical research and analysis is paramount in addressing the attendant issues presented by globalisation coupled with power shifts towards the newly emerging economies which have redefined the diplomatic landscape. These changing dynamics impose on the Ministry the onerous responsibility of ensuring coherent strategies are developed and deployed to adapt to these global realities while at the same time identifying the corresponding opportunities to enhance Kenya’s global competitiveness in line with the Kenya Vision 2030 and the Third Medium Term Plan. -

Martin Pj Edwardes an Anthropological Perspective

The Origins of Self explores the role that selfhood plays in defining human society, and each human individual in that society. It considers the genetic and cultural origins of self, the role that self plays in socialisation and language, and the types of self we generate in our individual journeys to and through adulthood. Edwardes argues that other awareness is a relatively early evolutionary development, present throughout the primate clade and perhaps beyond, but self-awareness is a product of the sharing of social models, something only humans appear to do. The self of which we are aware is not something innate within us, it is a model of our self produced as a response to the models of us offered to us by other people. Edwardes proposes that human construction of selfhood involves seven different types of self. All but one of them are internally generated models, and the only non-model, the actual self, is completely hidden from conscious awareness. We rely on others to tell us about our self, and even to let us know we are a self. Developed in relation to a range of subject areas – linguistics, anthropology, genomics and cognition, as well as socio-cultural theory – The Origins of Self is of particular interest to MARTIN P. J. EDWARDES students and researchers studying the origins of language, human origins in general, and the cognitive differences between human and other animal psychologies. Martin P. J. Edwardes is a visiting lecturer at King’s College London. He is currently teaching modules on Language Origins and Language Construction. -

Transitions: Fall 2016 Mcgill & the World

TRANSITIONS: 2016 FALL MCGILL & THE WORLD A PUBLICATION OF THE The BULL & BEAR EDITOR’S NOTE CONTENTS Jennifer Yoon Executive Editor FEATURE 4 Holding McGill Accountable 5 Humanities Under Attack 7 Two-Sides of a Coin: The Smoking Ban Shifting sands have never felt more unsettling. NEWS That’s only half a simile. The giant holes tearing up our campus streets are 8 Profile of Trump literally scrambling the soil beneath our feet. Apparently, our helmeted Supporters on Campus brigade of construction workers will be around for at least a few more years. What exactly are they working on again? Nobody knows. 10Indigenous Awareness Week Students are hurting from the myriad of changes, too. We’ve seen protests against austerity measures and for student workers’ rights. With classes BUSINESS & TECH and extracurriculars curtailed, students unsurprisingly take to the streets 11 Make Polling Great Again in protest – fulfilling a longstanding tradition amongst les étudiants 12 The Future of Food Montréalais. 14 Emergence of a Cashless Society And then, of course, there is the political fiasco South of the border. The election brought out the ugly in American society, terrifying women, racial minorities, LGBTQ folks, and more. Others began to seriously question ARTS & CULTURE the inherent value of previously revered democratic institutions: the 17 Crying in the Club with fourth estate, pluralism, and even foundational electoral processes. Venus 19 Skirting the Issues For many of us, 2016 has been a momentous year: in the course of these 21 Obituary: Public Libraries months, we’ve become accustomed a permanent state of uncertainty. (300 BC-2016 AD) 23 I Spend Way Too Much In this issue, we have tried to unpack some aspects of our increasingly unpredictable world – both on-campus, and off-campus. -

2012 EWDA Conference Program and Abstract Book.Pdf

Contents Welcome Address 5 Conference Program 7 Abstracts Oral Presentations 15 One Health Session 17 Population Health Assessment Session 34 Migration Session 48 WDA Student Research Recognition Award 51 Terry Amundson Award Student Session 52 Disease Control Session 72 Pathogenesis Session 79 Pathogen Discovery and Disease Emergence Session 86 Translocation and Reintroduction Session 89 Multiple Pollutants 92 Poster Presentations 93 Poster Session 1 95 Poster Session 2 217 Poster Session 3 325 Workshops 427 WDA EWDA 2012 Conference Scientific Committee 429 WDA EWDA 2012 Conference Organizing Committee 429 WDA 2012 Officers and Council 430 EWDA 2010/2012 Officers and Board 430 Index of Presenting Authors 433 WDA EWDA 2012: Site of Interest Map 437 Conference Overview 3 4 Welcome Address Dr. Bernard VALLAT, Directeur général de l'Organisation Mondiale de la Santé Animale (OIE), 12 rue de Prony, 75017 Paris The OIE welcomes participants to the “Convergence in wildlife health” Conference and is pleased to have been a partner for this successful event, alongside VetAgro Sup, the WDA and the EWDA. Movements of animals and people enable pathogens to travel faster than the incubation period of the epizootic diseases they cause and the health risks for humans, domestic animals and wildlife are rapidly evolving. Growth of the human population, climate change and increased land use are all factors that must be urgently taken into account to safeguard biodiversity on all continents. The Veterinary Services and veterinary teaching establishments must strengthen their capacities in the field of wildlife conservation and health management. New tools and new forms of collaboration and synergies need to be established between these services, wildlife specialists and users of the natural environment, which will in future provide valuable assistance in this field . -

Territory Characteristics Among Three Neighboring Chimpanzee Communities in the Taı¨ National Park, Coteˆ D’Ivoire

P1: FJT International Journal of Primatology [ijop] PP046-293191 March 9, 2001 10:45 Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999 International Journal of Primatology, Vol. 22, No. 2, 2001 Territory Characteristics among Three Neighboring Chimpanzee Communities in the Taı¨ National Park, Coteˆ d’Ivoire Ilka Herbinger,1,3 Christophe Boesch,1 and Hartmut Rothe2 Received May 11, 1999; revised February 7, 2000; accepted February 24, 2000 We studied territory characteristics among three neighboring chimpanzee communities in the Ta¨ı National Park, Coteˆ d’Ivoire, and compared them with other chimpanzee populations. We characterized territories and rang- ing patterns by analyzing six variables: (1) territory size, (2) overlap zone, (3) territory utilization, (4) core area, (5) territory shift, and (6) travel dis- tance. Data collection covered a period of 10 mo, during which we simultane- ously sampled the local positions of mostly large parties, including males in each community, in 30-min intervals. In Ta¨ı, chimpanzees used territories in a clumped way, with small central core areas being used preferentially over large peripheral areas. Although overlap zones between study communities mainly represented infrequently visited peripheral areas, overlap zones with all neighboring communities also included intensively used central areas. Ter- ritory utilization was not strongly seasonal, with no major shift of activity center or shift of areas used over consecutive months. However, we observed shorter daily travel distances in times of low food availability. Territory sizes of Ta¨ı chimpanzees tended to be larger than territories in other chimpanzee communities, presumably because high food availability allows for econom- ical defense of territorial borders and time investment in territorial activities. -

Structure and Evolution of the Gorilla and Orangutan Growth Hormone Loci

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sussex Research Online Structure and evolution of the gorilla and orangutan growth hormone loci. Antonio Ali Pérez-Maya1, Michael Wallis2, Hugo Alberto Barrera-Saldaña1*. 1Departamento de Bioquímica y Medicina Molecular, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Monterrey, Nuevo León 64460, México. 2Biochemistry and Biomedicine Group, School of Life Sciences, University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton, Sussex BN1 9QG, UK. Keywords: Growth hormone, chorionic somatomammotropin, Gorilla, Pongo. Short title: Gorilla & orangutan GH loci. * Correspondence: Dr. Hugo A. Barrera-Saldaña. Departamento de Bioquímica y Medicina Molecular. Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. Av. Madero y Dr. Aguirre Pequeño, Col. Mitras Centro. Monterrey, Nuevo León, México 64460. Tel.: +52 81 83294173 x2591; fax: +52 81 83337747. E-mail: [email protected] 1 ABSTRACT In primates, the unigenic growth hormone (GH) locus of prosimians, expressed primarily in the anterior pituitary, evolved by gene duplications, independently in New World Monkeys (NWM) and Old World Monkeys (OWMs)/apes, to give complex clusters of genes expressed in the pituitary and placenta. In human and chimpanzee, the GH locus comprises five genes, GH-N being expressed as pituitary GH, whereas GH-V (placental GH) and CSHs (chorionic somatomammotropins) are expressed (in human and probably chimpanzee) in the placenta; the CSHs comprise CSH-A, CSH-B and the aberrant CSH-L (possibly a pseudogene) in human, and CSH-A1, CSH-A2 and CSH-B in chimpanzee. Here the GH locus in two additional great apes, gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) and orangutan (Pongo abelii), is shown to contain six and four GH-like genes respectively. -

Food Competition and Linear Dominance Hierarchy Among Female Chimpanzees of the Taï

P1: IZO International Journal of Primatology [ijop] pp895-ijop-467726 June 27, 2003 20:7 Style file version Nov. 18th, 2002 International Journal of Primatology, Vol. 24, No. 4, August 2003 (C 2003) Food Competition and Linear Dominance Hierarchy among Female Chimpanzees of the Taı¨ National Park Roman M. Wittig1 and Christophe Boesch1 Received April 24, 2002; revision October 15, 2002; accepted January 20, 2003 Dominance rank in female chimpanzees correlates positively with reproduc- tive success. Although a high rank obviously has an advantage for females, clear (linear) hierarchies in female chimpanzees have not been detected. Fol- lowing the predictions of the socio-ecological model, the type of food competi- tion should affect the dominance relationships among females. We investigated food competition and relationships among 11 adult female chimpanzees in the Ta¨ı National Park, Coteˆ d’Ivoire (West Africa). We detected a formal linear dominance hierarchy among the females based on greeting behaviour directed from the subordinate to the dominant female. Females faced contest compe- tition over food, and it increased when either the food was monopolizable or the number of competitors increased. Winning contests over food, but not age, was related to the dominance rank. Affiliative relationships among the females did not help to explain the absence of greetings in some dyads. How- ever comparison post hoc among chimpanzee study sites made differences in the dominance relationships apparent. We discuss them based on social relationships among females, contest competition and predation. The cross- site comparison indicates that the differences in female dominance hierarchies among the chimpanzee study sites are affected by food competition, predation risk and observation time.