Food Competition and Linear Dominance Hierarchy Among Female Chimpanzees of the Taï

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

But Should They Be? and What Is a Dominance Hierarchy Anyways?

Myrmecological News 24 71-81 Online Earlier, for print 2017 Dominance hierarchies are a dominant paradigm in ant ecology (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), but should they be? And what is a dominance hierarchy anyways? Katharine L. STUBLE, Ivan JURIĆ, Xim CERDÁ & Nathan J. SANDERS Abstract There is a long tradition of community ecologists using interspecific dominance hierarchies as a way to explain species coexistence and community structure. However, there is considerable variation in the methods used to construct these hierarchies, how they are quantified, and how they are interpreted. In the study of ant communities, hierarchies are typ- ically based on the outcome of aggressive encounters between species or on bait monopolization. These parameters are converted to rankings using a variety of methods ranging from calculating the proportion of fights won or baits monopolized to minimizing hierarchical reversals. However, we rarely stop to explore how dominance hierarchies relate to the spatial and temporal structure of ant communities, nor do we ask how different ranking methods quantitatively relate to one another. Here, through a review of the literature and new analyses of both published and unpublished data, we highlight some limitations of the use of dominance hierarchies, both in how they are constructed and how they are interpreted. We show that the most commonly used ranking methods can generate variation among hierarchies given the same data and that the results depend on sample size. Moreover, these ranks are not related to resource acquisition, suggest- ing limited ecological implications for dominance hierarchies. These limitations in the construction, analysis, and interpre- tation of dominance hierarchies lead us to suggest it may be time for ant ecologists to move on from dominance hierarchies. -

Dominance and Prestige: Dual Strategies for Navigating Social Hierarchies

CHAPTER THREE Dominance and Prestige: Dual Strategies for Navigating Social Hierarchies J.K. Maner*,1, C.R. Case*,† *Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, United States †Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, United States 1Corresponding author: e-mail address: [email protected] Contents 1. Dominance and Prestige as Evolved Strategies for Navigating Social Hierarchies 132 1.1 Social Hierarchies in Evolutionary Perspective 132 1.2 The Motivational Psychology of Social Rank 133 1.3 Dominance 134 1.4 Prestige 137 1.5 Summary 139 2. When Leaders Selfishly Sacrifice Group Goals 141 2.1 Primary Hypotheses 143 2.2 Tactics Dominant Leaders Use to Protect Their Social Rank 145 2.3 From Me vs You to Us vs Them 161 2.4 Summary 162 3. Dual-Strategies Theory: Future Directions and Implications for the Social Psychology of Hierarchy 164 3.1 Identifying Additional Facets of Dominance and Prestige 164 3.2 Additional Moderating Variables 165 3.3 The Pitfalls of Prestige 167 3.4 Rising Through the Ranks 169 3.5 The Psychology of Followership 170 3.6 Sex Differences 172 3.7 Intersections Between Dominance and Prestige and the Broader Social Psychological Literature on Hierarchy 173 4. Conclusion 174 References 175 Abstract The presence of hierarchy is a ubiquitous feature of human social groups. An evolution- ary perspective provides novel insight into the nature of hierarchy, including its causes and consequences. When integrated with theory and data from social psychology, an evolutionary approach provides a conceptual framework for understanding the # Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Volume 54 2016 Elsevier Inc. -

Social Dominance in Childhood and Its Evolutionary Underpinnings: Why It Matters and What We Can Do

SUPPLEMENT ARTICLE Social Dominance in Childhood and Its Evolutionary Underpinnings: Why It Matters and What We Can Do AUTHOR: Patricia H. Hawley, PhD Bullying is a common and familiar manifestation of power differentials Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas and social hierarchy. Much has been written lately about bullying in KEY WORDS schools, in the workplace, and even in the National Football League. Such aggression, bullying, evolution, social dominance hierarchies are pervasive in nature. They can be subtly, almost imper- Dr Hawley conceptualized and designed the article, drafted and ceptibly, managed (by glances, gestures, or implicit cultural expectations), revised the manuscript, and approved the manuscript as brutally enforced (authoritarian rule, vicious attacks, or explicit edicts), or submitted. anything in between. These power differentials affect our daily behaviorand www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2014-3549D thought processes, are a large source of our psychosocial stress, and doi:10.1542/peds.2014-3549D influence our health and well-being. Accepted for publication Dec 19, 2014 As an evolutionary developmental psychologist focusing on aggression and Address correspondence to Patricia H. Hawley, PhD, 3008 18th St, Box 41071, Lubbock, TX 79409-41071. E-mail: patricia.hawley@ttu. peer relationships in childhood, I present for this article an evolutionary view edu to children’s social functioning as it relates to power differentials. First, 3 PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275). common errors in thinking about dominance are dispelled. The discussion Copyright © 2015 by the American Academy of Pediatrics next focuses on social dominance in childhood, including how humans FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The author has indicated she has no appear to be prepared to think about and navigate these relationships, how financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. -

Social Dominance and Reproductive Differentiation Mediated By

© 2015. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | The Journal of Experimental Biology (2015) 218, 1091-1098 doi:10.1242/jeb.118414 RESEARCH ARTICLE Social dominance and reproductive differentiation mediated by dopaminergic signaling in a queenless ant Yasukazu Okada1,2,*, Ken Sasaki3, Satoshi Miyazaki2,4, Hiroyuki Shimoji2, Kazuki Tsuji5 and Toru Miura2 ABSTRACT (i.e. the unequal sharing of reproductive opportunity) is widespread In social Hymenoptera with no morphological caste, a dominant female in various animal taxa (Sherman et al., 1995; birds, Emlen and becomes an egg layer, whereas subordinates become sterile helpers. Wrege, 1992; mammals, Jarvis, 1981; Keane et al., 1994; Nievergelt The physiological mechanism that links dominance rank and fecundity et al., 2000). In extreme cases, it can result in the reproductive is an essential part of the emergence of sterile females, which reflects division of labor, such as in social insects and naked mole rats the primitive phase of eusociality. Recent studies suggest that (Wilson, 1971; Sherman et al., 1995; Reeve and Keller, 2001). brain biogenic amines are correlated with the ranks in dominance In highly eusocial insects (honeybees, most ants and termites), hierarchy. However, the actual causality between aminergic systems developmental differentiation of morphological caste is the basis of and phenotype (i.e. fecundity and aggressiveness) is largely unknown social organization (Wilson, 1971). By contrast, there are due to the pleiotropic functions of amines (e.g. age-dependent morphologically casteless social insects (some wasps, bumblebees polyethism) and the scarcity of manipulation experiments. To clarify and queenless ants) in which the dominance hierarchy plays a central the causality among dominance ranks, amine levels and phenotypes, role in division of labor. -

Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (Genus: Pongo)- the Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2015 Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-121397 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia. Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation. 2015, University of Zurich, Faculty of Science. Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (genus: Pongo) — The Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr. sc. nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch‐naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Maja Patricia Mattle‐Greminger von Richterswil (ZH) Promotionskomitee Prof. Dr. Carel van Schaik (Vorsitz) PD Dr. Michael Krützen (Leitung der Dissertation) Dr. Maria Anisimova Zürich, 2015 To my family Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................ 1 Summary ..................................................................................................................... 3 Zusammenfassung ..................................................................................................... -

Why We Live in Hierarchies: a Quantitative Treatise

Why we live in hierarchies: a quantitative treatise by Anna Zafeiris1 and Tamás Vicsek1, 2 1Statistical and Biological Physics Research Group of HAS 2Department of Biological Physics, Eötvös University Preprint version Final version to be published by Springer as part of SpringerBriefs in Physics series. July 2017 1 Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 General considerations ................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Motivation ...................................................................................................................... 8 1.3 Hierarchical structures in space and in networks .......................................................... 9 Reference list ..................................................................................................................... 10 2 Definitions and Basic Concepts .......................................................................................... 12 2.1 Describing hierarchical structures ............................................................................... 17 2.1.1 Graphs and networks ............................................................................................ 17 2.1.2 Measuring the level of hierarchy .......................................................................... 19 2.1.3 Classification of hierarchical networks ............................................................... -

Hierarchical Classification by Rank and Kinship in Baboons

R EPORTS the study period into one “premove” and two “post- 23. T. E. Seeman, B. H. Singer, C. D. Ryff, G. D. Love, L. 34. STATA 8.0, Stata, College Station, TX (2003). move” periods. For Hook’s Group, which was ob- Levy-Storms, Psychosomatic Med. 64, 395 (2002). 35. We thank the Office of the President of Kenya and the served for 9 years before the move and 7 years after 24. W. L. Gardner, S. Gabriel, A. B. Diekman, in Handbook Kenya Wildlife Service for permission to work in Am- the move, we divided the study period into two of Psychophysiology, J. T. Cacioppo, L. G. Tassinary, boseli; the staffs of the National Museums of Kenya, the premove and one postmove periods. We calculated G. G. Berntson, Eds. (Cambridge Univ. Press, New Kenya Wildlife Service, and Amboseli National Park for the value of the composite sociality index for each York, 2000), pp. 643–664. cooperation and assistance; the members of the pasto- female during each time period using the median 25. J. T. Cacioppo et al., Int. J. Psychophysiol. 35, 143 (2000). ralist communities of Amboseli and Longido and the values of the three behavioral measures derived from 26. N. L. Collins, C. Dunkel-Schetter, M. Lobel, S. C. Institute for Primate Research in Nairobi for assistance each time period for each group. We computed the Scrimshaw, J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 65, 1243 (1993). and local sponsorship; R. Mututua, S. Sayialel, P. Mu- adjusted value of relative infant survival as the dif- 27. T. E. Seeman, B. -

Dimensional Investment Group

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM N-Q Quarterly schedule of portfolio holdings of registered management investment company filed on Form N-Q Filing Date: 2008-04-29 | Period of Report: 2008-02-29 SEC Accession No. 0001104659-08-027772 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER DIMENSIONAL INVESTMENT GROUP INC/ Business Address 1299 OCEAN AVE CIK:861929| IRS No.: 000000000 | State of Incorp.:MD | Fiscal Year End: 1130 11TH FLOOR Type: N-Q | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-06067 | Film No.: 08784216 SANTA MONICA CA 90401 2133958005 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM N-Q QUARTERLY SCHEDULE OF PORTFOLIO HOLDINGS OF REGISTERED MANAGEMENT INVESTMENT COMPANY Investment Company Act file number 811-6067 DIMENSIONAL INVESTMENT GROUP INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in charter) 1299 Ocean Avenue, Santa Monica, CA 90401 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Catherine L. Newell, Esquire, Vice President and Secretary Dimensional Investment Group Inc., 1299 Ocean Avenue, Santa Monica, CA 90401 (Name and address of agent for service) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: 310-395-8005 Date of fiscal year end: November 30 Date of reporting period: February 29, 2008 ITEM 1. SCHEDULE OF INVESTMENTS. Dimensional Investment Group Inc. Form N-Q February 29, 2008 (Unaudited) Table of Contents Definitions of Abbreviations and Footnotes Schedules of Investments U.S. Large Cap Value Portfolio II U.S. Large Cap Value Portfolio III LWAS/DFA U.S. High Book to Market Portfolio DFA International Value Portfolio Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. -

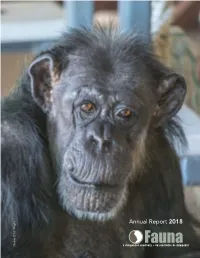

Annual Report 2018 Blackie © NJ Wight Help Us Secure Their Future

Annual Report 2018 Blackie © NJ Wight Help Us Secure Their Future HelpLIFETIME CAREUs FUND Secure Their Future Established in 2007, the Fauna Lifetime Care Fund is our promise to the Fauna chimpanzees for a lifetime of the quality care they so deserve. MONTHLY DONATION Please email us at [email protected] to set up this form of monthly giving via cheque or credit card. ONLINE • CanadaHelps.org, enter the searchtype, charity name: Fauna Foundation and it will take you directly to the link. • FaunaFoundation.org, donate via PayPal PHONE 450-658-1844 FAX 450-658-2202 MAIL Fauna Foundation 3802 Bellerive Carignan,QC J3L 3P9 They need our help—not just today but tomorrow too. Toby © Jo-Anne McArthur Toby Help me keep my promise to them. Your donation today in whatever amount you can afford means so much! Billing Information Payment Information Name: ________________________________________________ o $100 o $75 o $50 o $25 o Other $ ______ Address: ______________________________________________ o Check enclosed (payable to Fauna) City: ___________________Province/State: _________________ o Visa o Mastercard Postal Code/Zip Code:__________________________________ o o Tel: (____)_____________________________________________ Monthly pledge $ ______ Lifetime Care Fund $ ______ Email: ________________________________________________ Card Number: ______________________________________ In o honor of or in o memory of ___________________________ Exp: ___/___/___ Signature: __________________________ Or give online at www.faunafoundation.org -

Determinants of Reproductive Status and Mate Choice in Captive Colonies of the Naked Mole-Rat, Heterocephalus Glaber

DETERMINANTS OF REPRODUCTIVE STATUS AND MATE CHOICE IN CAPTIVE COLONIES OF THE NAKED MOLE-RAT, HETEROCEPHALUS GLABER FRANK M. CLARKE A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy OCTOBER 1998 ProQuest Number: 10609357 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10609357 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 I declare that I have conducted the work in this thesis, that I have composed this thesis, that all the quotations and sources of information have been acknowledged and that this work has not previously been accepted in an application for a degree. Frank Clarke Abstract Naked mole-rats are small, fossorial, cooperatively breeding rodents with a high reproductive skew. Wild colonies contain around 80 individuals and reproduction is monopolised by a single female, the 'queen', and one to three males. This study investigates the hormonal, behavioural, and genetic correlates of dominance and breeding status in captive colonies. I examine the relationship between dominance rank, reproductive status, and urinary testosterone and cortisol levels, and try to determine whether physiological and behavioural parameters can be used as predictors of succession by experimentally removing breeders. -

Martin Pj Edwardes an Anthropological Perspective

The Origins of Self explores the role that selfhood plays in defining human society, and each human individual in that society. It considers the genetic and cultural origins of self, the role that self plays in socialisation and language, and the types of self we generate in our individual journeys to and through adulthood. Edwardes argues that other awareness is a relatively early evolutionary development, present throughout the primate clade and perhaps beyond, but self-awareness is a product of the sharing of social models, something only humans appear to do. The self of which we are aware is not something innate within us, it is a model of our self produced as a response to the models of us offered to us by other people. Edwardes proposes that human construction of selfhood involves seven different types of self. All but one of them are internally generated models, and the only non-model, the actual self, is completely hidden from conscious awareness. We rely on others to tell us about our self, and even to let us know we are a self. Developed in relation to a range of subject areas – linguistics, anthropology, genomics and cognition, as well as socio-cultural theory – The Origins of Self is of particular interest to MARTIN P. J. EDWARDES students and researchers studying the origins of language, human origins in general, and the cognitive differences between human and other animal psychologies. Martin P. J. Edwardes is a visiting lecturer at King’s College London. He is currently teaching modules on Language Origins and Language Construction. -

Transitions: Fall 2016 Mcgill & the World

TRANSITIONS: 2016 FALL MCGILL & THE WORLD A PUBLICATION OF THE The BULL & BEAR EDITOR’S NOTE CONTENTS Jennifer Yoon Executive Editor FEATURE 4 Holding McGill Accountable 5 Humanities Under Attack 7 Two-Sides of a Coin: The Smoking Ban Shifting sands have never felt more unsettling. NEWS That’s only half a simile. The giant holes tearing up our campus streets are 8 Profile of Trump literally scrambling the soil beneath our feet. Apparently, our helmeted Supporters on Campus brigade of construction workers will be around for at least a few more years. What exactly are they working on again? Nobody knows. 10Indigenous Awareness Week Students are hurting from the myriad of changes, too. We’ve seen protests against austerity measures and for student workers’ rights. With classes BUSINESS & TECH and extracurriculars curtailed, students unsurprisingly take to the streets 11 Make Polling Great Again in protest – fulfilling a longstanding tradition amongst les étudiants 12 The Future of Food Montréalais. 14 Emergence of a Cashless Society And then, of course, there is the political fiasco South of the border. The election brought out the ugly in American society, terrifying women, racial minorities, LGBTQ folks, and more. Others began to seriously question ARTS & CULTURE the inherent value of previously revered democratic institutions: the 17 Crying in the Club with fourth estate, pluralism, and even foundational electoral processes. Venus 19 Skirting the Issues For many of us, 2016 has been a momentous year: in the course of these 21 Obituary: Public Libraries months, we’ve become accustomed a permanent state of uncertainty. (300 BC-2016 AD) 23 I Spend Way Too Much In this issue, we have tried to unpack some aspects of our increasingly unpredictable world – both on-campus, and off-campus.