Fall 1996 Number 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Family Law Section Chair Mitchell Y

NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION Family Law Section Chair Mitchell Y. Cohen, Esq. Johnson & Cohen LLP White Plains Program Co-Chairs Rosalia Baiamonte, Esq. Gassman Baiamonte Gruner, P.C. Garden City NYSBA Dylan S. Mitchell, Esq. Blank Rome LLP New York City Family Law Section Peter R. Stambleck, Esq. Aronson Mayefsky & Sloan, LLP Summer Meeting New York City Family Law Section The Newport Marriott Hotel CLE Committee Co-Chairs Rosalia Baiamonte, Esq. 25 Americas Cup Ave. Gassman Baiamonte Gruner, PC Garden City Newport, RI Henry S. Berman, Esq. Berman Frucco Gouz Mitchel & Schub PC July 13–16, 2017 White Plains Charles P. Inclima, Esq. Inclima Law Firm, PLLC Rochester Peter R. Stambleck, Esq. Aronson Mayefsky & Sloan, LLP New York City Under New York’s MCLE rule, this program may qualify for UP Bruce J. Wagner, Esq. TO 6.5 MCLE credits hours in Areas of Professional Practice. This McNamee, Lochner, Titus & program is not transitional and is not suitable for MCLE credit for Williams, P.C. newly-admitted attorneys. Albany SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Thursday, July 13 9:00 a.m. – 10:30 a.m. Officers Meeting 12:00 p.m. Registration and Exhibits — South Foyer 2:00 p.m. – 4:30 p.m. Executive Committee Meeting — Salons II, III, IV 6:00 p.m. – 10:00 p.m. Kid’s Dinner & Activities — Portsmouth Room 6:15 p.m. Shuttle will leave for the reception/dinner at the Newport Yachting Center (Bohlin); The shuttle will run a continuous loop 6:30 p.m. – 9:30 p.m. Reception and lobster bake at the Newport Yachting Center (Bohlin) Friday, July 14 7:30 a.m. -

Libertarian Party of Nevada Hosted "Speed Dating" Events Over 2 Days at Different Venues in Las Vegas

Endorsement Committee This year, we formed an Endorsement Committee comprised of 18 members plus additional Libertarian leadership; the “Committee.” The Committee members conducted their own independent research on each of the candidates and asked them questions at our events. The Committee members took notes and made recommendations on grades and endorsements. Endorsement Committee Chair: Jason Weinman Committee Members: Jason G Smith Jim Duensing Jason Nellis Lesley Chan John McCormack JD Smith Lou Pombo Brady Bowyer Scott Lafata Tim Hagan Brett H. Pojunis Brandon Ellyson Debra Dedmon Nick Klein Andrew Lea Ross Williams Tarina Dark Steve Brown Format - Why "Speed Dating?" The Libertarian Party of Nevada hosted "Speed Dating" events over 2 days at different venues in Las Vegas. The goal was to meet as many candidates as possible in a format similar to speed dating. LPNevada endorsed Candidates in non‐partisan races and graded Candidates in partisan races for the 2014 General Elections. Most organizations do not get one‐on‐one interaction with the candidates; we felt this is important. Endorsements and Grading Non‐Partisan candidates received either a positive (thumbs up) or negative (thumbs down) endorsement from the Committee. Partisan Candidates received a grade of 1 to 5 stars. Candidates who received 1 star were not very Libertarian and candidates who received 5 stars were very good in regards to their position on issues important to Libertarians. The Libertarian Party of Nevada has the following 15 Candidate on the 2014 Ballot. Adam Sanacore, Assembly District 21 Lou Pombo, Assembly District 37 Chris Dailey, White Pine County Commission Louis Gabriel, Assembly District 32 Donald W. -

Addendum a to Resolution to Reestablish Republican Unity and Principles

Addendum A to Resolution to Reestablish Republican Unity and Principles Note: This addendum is attached to the Resolution to ensure clarity and justification for the claims and appeals made within the Resolution. Towards Integrity, Then Unity We, the Nevada Republican Central Committee make it known that we delayed presentation and publication of this Resolution until after the 2012 Presidential Election to unmistakably demonstrate support and respect for our Republican candidate. Unlike events at the 2012 Republican National Committee (RNC) Tampa Convention, we demand integrity and sincere unity in Republican Party affairs. The RNC silenced the delegates, and therefore, all Republicans, during the vote to accept the RNC Rules Committee Report, in violation of RNC Rules, specifically, our Preamble. The Preamble of our RNC Rules sets out a clear vision for the Party to function properly. The leadership of the Party exercised exceptionally poor judgment in their decision making, clearly violating that Preamble. As members of the Republican Party it is our duty to take actions necessary to ensure that our Party respects our rules. Specific Grievances 1) The report of the 2012 RNC Convention Rules Committee was not accepted properly. Legitimate cries of “Division” were heard, clearly requiring actions which were not taken (see Rules of the House of Representatives, Rule XX, 1. (a) Voting and Quorum Calls) 2) Therefore, Rule 40 (b) could not have been amended and the original requirement for five states remained the criteria. Considering this and that the RNC Secretary was handed candidate nomination forms in accordance with the rules, there should have been a nomination from the floor. -

Regular Vendors

Regular Vendors Regular Vendors $ 331,291,537.80 1ST RESPONSE TOWING INC 167223 $ 340.00 20/20 GENESYSTEMS 110917 $ 2,545.00 22ND CENTURY STAFFING INC 166767 $ 22,307.25 2900 CHARLESTON LLC 175674 $ 1,758.00 3 B'S INC 130384 $ 885.79 333 6TH STREET LLC 165858 $ 66,150.00 3D VISIONS INC 163619 $ 2,645.00 3M COMPANY 139423 $ 1,306.42 3M COMPANY 102220 $ 30,247.34 4 WALL ENTERTAINMENT 127107 $ 1,548.50 4LEAF CONSULTING LLC 160792 $ 89,600.00 5 ROCK HEADS LLC 104921 $ 271.00 5.11 TACTICAL 175645 $ 1,280.00 702FIRM LLC 175959 $ 4,000.00 707 PROPERTY MANAGEMENT 170884 $ 1,546.00 A & A UNIFORMS INC 102856 $ 619.25 A & B SECURITY GROUP INC 103501 $ 6,426.60 A A CASSARO PLUMBING 124982 $ 90.52 A BACA &/OR WYOMING C S 132102 $ 3,046.14 A CARROLL &/OR US DEP OF 173243 $ 437.92 EDUCATION A CHALANA-GRAY &/OR CONSTABLE 175137 $ 1,557.47 A COMPANY INC 102887 $ 250.00 A D L HOME CARE INC 103985 $ 33,008.00 A DAVIS & OR STATE DISBURSEMENT 140448 $ 552.96 A DIV OF LORMAN BUSINESS CTR INC 101342 $ 199.00 A GARBUTT &/OR LV CONSTABLE 157962 $ 750.00 A GARBUTT &/OR US TREASURY 162481 $ 750.00 A HELPING HAND HOME HEALTH CARE 106117 $ 58,144.00 INC A HONEY WAGON INC 138408 $ 27,597.50 A KING &/OR MISDU 154359 $ 1,582.08 A MEDINA &/OR CONSTABLE 176236 $ 460.61 A NLV CAB CO 100177 $ 1,071.77 A RICON AND OR 174083 $ 951.97 A RIFKIN CO 106406 $ 4,988.00 A S K ASSOCIATES INC 169495 $ 300.00 A STORAGE ON WHEELS INC 103702 $ 275.00 A THOMAS &/OR MICHIGAN STATE 176165 $ 235.17 A TO ZZZ INC 103195 $ 47,154.20 A-1 AUTOMATION & CONTROLS LLC 171481 $ 1,243.75 A-1 NATIONAL -

Southern Hills Republican Women Mission Statement DIRECTORS the Southern Hills Republican Women’S Club Believes in American Exceptionalism

Volume 7 Issue 4 APRIL 2014 Southern Hills Republican Women Mission Statement DIRECTORS The Southern Hills Republican Women’s Club believes in American exceptionalism. We are President: committed to supporting and advancing the Republican Party, and its candidates, at the local, Lynn Armanino state and national level. To fulfill this mission we will: [email protected] 248-1414 • provide information on current political and community issues, • organize members and coordinate efforts to promote and elect Republican candidates, Interim1st V.P: • maintain our commitment, passion and knowledge in support of the Republican Party and Nickie Diersen conservative issues, [email protected] • influence policy making at all levels of government. 897-4682 2nd V.P: Angela Lin Greenberg- nd [email protected]; Tuesday April 22 269-5557 Guest Speaker Senator Barbara Cegavske Treasurer: Susan Tanksley Candidate for Nevada Secretary of State [email protected] 487-6418 Secretary: Barbara has served for 18 years in our state legislature and has worked very Linda Schlinger hard to enact legislation in support of families and businesses in our great state of [email protected] rd 896-9829 Nevada. She just completed her 3 and final term in our State Senate (District 8) and held the following leadership positions: Senate Minority Whip (2009) and Communications Director: Assistant Senate Minority Leader (2011) along with other chairmanship and Nickie Diersen committee membership positions. [email protected]; 897-4682 Prior to this she served in our State Assembly (District 5) for 6 years and held Events Director: numerous legislative leadership positions including Assistant Assembly Minority Anne Danielson [email protected] Whip (1997) and Assistant Minority Leader (1999 – 2001). -

The Arrival of the Fittest: How the Great Become Great (Dorris, 2011)

Greatness: How The Great Become Great… and You & I Don’t Bill Dorris, Ph.D. School of Communications Dublin City University Dublin 9, Ireland © 2020 Contents Contents 2 Note to Users 4 Blog and Reading Tips 5 Brief Bio and Endorsements 7 Acknowledgments 9 Introduction 12 How The Great Become Great – The Analysis 13 Key Characteristics 15 The Right Kind of Problems 17 Flow Activities & Escape Activities 20 How Many Potential Greats? 24 Generational Problems 25 Community of Birth 28 Matching the Person with The Right Kind of Problems - The Arrival of The Fittest 30 Organizations and Teams 32 Continuous Matching 33 Links 36 Cumulative Matching 38 Catalytic Matching 43 2 Catalytic Accelerations to Greatness 51 Chaotic Matching 56 Spwins 60 Spwins from Beginning to End 74 Where to look for Spwins 79 Women and Other Outsiders 90 How The Great Become Great - Implications 99 And as for Heroes? 99 What's It All Mean? 102 And You & I 107 einstein and santa claus 113 Notes 115 References 264 Indices 309 Greats 309 Concepts 313 Authors 317 3 Note to `Users Greatness is written for Anyone who is interested in the question of How The Great Become Great... and You & I Don't. This includes the general public, university students, and academics as well. How so? Simple. The Text of this book is written almost in story form, with barely a hint of academic research to be seen, so it can be easily read by anyone. As for the academic research, it is thoroughly discussed and easily accessible in the book's Notes, when and if you're interested. -

AUGUST 2017 – the Elephant’S Tale

C ELEBRATING 52 YEARS • 1965 - 2015 – AUGUST 2017 – The Elephant’s Tale V OLUME 24 • I SSUE 8 Please join us for A Summer Garden Party TUESDAY, AUGUST 8, 2017 With Special Invited Guest Congressman Mark Amodei, Who will be introduced by our Secretary of State, Barbara Cegavske Where: Janet Pahl’s Garden, 1064 Lakeshore Boulevard, Incline Village | 5 to 8 p.m $50 with advance reservation, $55 without Members! This is our last chance this year to reach like - minded women who may have difficulty attending luncheon meetings. PLEASE invite your friends and contacts. Don’t forget to wear your club name badge! PLEASE RSVP to Shirley Appel at [email protected] or by calling (cell) 818 - 266 - 4402 or (home) 775 - 831 - 1505 by FRIDAY, AUGUST 4th AND Mail your check to: IVCBRW, PO BOX 3009, INCLINE VILLAGE, NV 89450 Your check is your reservation! Paid for by Incline Village/Crystal Bay Republican Women. Political contributions are not tax deductible. All solicitations of funds in connection with this event are being made by the Incline Village/Crystal Bay Republican Women and not by Congressman Amodei. Congressman Amodei is seeking only federal permissible funds subject to federal limitations, prohibitions and reporting requirements. Not endorsed by any candidate or candidate’s committee. T HE E LEPHANT ’ S T ALE • A UGUST 2017 with cocktails starting at 5:00 PM and dinner at 6:00 PRESIDENT’S PM. Please make your reservations early. This is the MESSAGE annual “pay in advance” garden party. See the flyer in this newsletter to RSVP. -

POST-ELECTION CASES UPDATED 11/4/20 at 7:00 PM

VOTING RIGHTS LITIGATION: POST-ELECTION CASES UPDATED 11/4/20 at 7:00 PM CASE ISSUE DEVELOPMENTS PENNSYLVANIA Republican Party of Pennsylvania v. Trump campaign claims that state supreme Trump filed a motion to intervene before Boockvar, No. 20-542 (U.S.) court ruling that extended ballot receipt the Supreme Court. deadline to November 6 violates the Elections/Electors Clause. The Supreme Court has ordered a response to be filed by 5pm tomorrow (11/5) In re Canvassing Observation, No. 1094 CD Trump campaign argues that counting Trump campaign appeals ruling by Election 2020 (Commonwealth Ct. of Pa.) should temporarily stop until observers Day judge that denied greater access. A are given greater access to watch the hearing has been scheduled for 7pm on ballot count. 11/4. Contemporaneous coverage of proceedings here: https://twitter.com/broadandmarket/stat us/1323794598951587841?s=21 Hamm v. Boockvar, No. 600 MD 2020 Plaintiffs challenge guidance recently Filed late 11/3. Status conference (Commonwealth Ct. of Pa.) issued by the Secretary of the scheduled for 1:30 Wed 11/4. Commonwealth, arguing that her instruction that county boards of election communicate with voters whose ballots The Voter Protection Program (VPP) is a national nonpartisan initiative promoting election integrity and ensuring safe, fair, and secure elections. Learn more at voterprotectionprogram.org are found to be deficient during the pre- canvass process violates state law. In their view, this process, as well as any process for allowing voters to “cure” their vote with a provisional ballot, violates Pennsylvania law, and they ask the court to enjoin the Secretary from allowing invalidly “cured” ballots to be counted in the vote totals. -

Dan De Quille Papers, [Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf65800586 No online items Guide to the Dan De Quille Papers, [ca. 1860-1914] Processed by The Bancroft Library staff The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note Arts and Humanities --Literature --American LiteratureHistory --History, United States (excluding California) --History, NevadaGeographical (By Place) --United States (excluding California) --Nevada Guide to the Dan De Quille BANC MSS P-G 246 1 Papers, [ca. 1860-1914] Guide to the Dan De Quille Papers, [ca. 1860-1914] Collection number: BANC MSS P-G 246 The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Contact Information: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu Processed by: The Bancroft Library staff Encoded by: Hernán Cortés © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Dan De Quille Papers, Date (inclusive): [ca. 1860-1914] Collection Number: BANC MSS P-G 246 Creator: De Quille, Dan, 1829-1898 Extent: Number of containers: 3 boxes, 2 cartons, 1 oversize folder Repository: The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California 94720-6000 Physical Location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the Library's online catalog. Abstract: Letters concerning the Territorial Enterprise, Mark Twain, and the writing of his book on the Big Bonanza ; manuscripts of sketches written for newspapers and magazines; clippings; notes and notebooks; a few papers of other members of his family. -

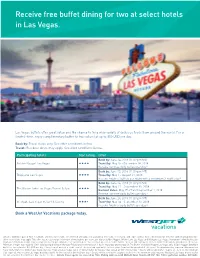

Receive Free Buffet Dining for Two at Select Hotels in Las Vegas

Receive free buffet dining for two at select hotels in Las Vegas. Las Vegas buffets offer great value and the chance to try a wide variety of delicious foods from around the world. For a limited-time, enjoy complimentary buffet for two valued at up to $50 USD per day. Book by: Travel dates vary. See offer conditions below. Travel: Blackout dates may apply. See offer conditions below. Participating hotels Star rating Offer Book by: June 24, 2018 (11:59 pm MT) Golden Nugget Las Vegas Travel by: May 15 - December 28, 2018 Receive two free daily buffets per day.1 Book by: June 15, 2018 (11:59 pm MT) Tropicana Las Vegas Travel by: May 1 - August 31, 2018 Receive two free buffets per room with a minimum 3-night stay.2 Book by: June 24, 2018 (11:59 pm MT) Travel by: May 17 - September 30, 2018 The Westin Lake Las Vegas Resort & Spa Backout dates: May 25-27 and September 1, 2018 Receive two free daily buffets per day.3 Book by: June 24, 2018 (11:59 pm MT) Westgate Las Vegas Resort & Casino + Travel by: May 14 - September 30, 2018 Receive two free daily buffets per day.4 Book a WestJet Vacations package today. Advance booking required. Non-refundable and non-transferable. Offer limited and subject to availability. Offer subject to change and expire without notice. New bookings only. Not valid on group bookings. Other restrictions may apply. This offer has no cash value. Maximum of two buffets per room, per day at Golden Nugget, Westin Lake Las Vegas and Westgate Las Vegas. -

Cultural Resources Overview of the Heinz Ranch, South Parcel (Approximately 1378 Acres) for the Stone Gate Master Planned Community, Washoe County, Nevada

Cultural Resources Overview of the Heinz Ranch, South Parcel (approximately 1378 acres) for the Stone Gate Master Planned Community, Washoe County, Nevada Project Number: 2016-110-1 Submitted to: Heinz Ranch Company, LLCt 2999 Oak Road, Suite 400 Walnut Creek, CA 94597 Prepared by: Michael Drews Dayna Giambastiani, MA, RPA Great Basin Consulting Group, LLC. 200 Winters Drive Carson City, Nevada 89703 July7, 2016 G-1 Summary Heinz Ranch was established in 1855 by Frank Heinz, an emigrant from Germany, who together with his wife Wilhelmina, turned it into a profitable cow and calf operation (Nevada Department of Agriculture 2016). In 2004, Heinz Ranch received the Nevada Centennial Ranch and Farm award from the Nevada Department of Agriculture for being an active ranch for over 100 years. A Class II archaeological investigation of the property was conducted in May and June 2016. Several prehistoric archaeological sites have been recorded on the property. Habitation sites hold the potential for additional research and have previously been determined eligible to the National Register of Historic Places. Historic sites relating to mining and transportation along with the ranching landscape are also prominent. Architectural resources on the property consist of several barns, outbuildings and residences. The barns are notable for their method of construction. Many are constructed of hand hewn posts and beams, and assembled with pegged mortise and tenon joinery. They date to the earliest use of the ranch. Residences generally date to the 1930s. Historic sites and resources located on Heinz Ranch provide an opportunity for more scholarly research into the prehistory and history of Cold Springs Valley (also Laughton’s Valley) and the region in general. -

May 2010 Room Keys Standard Room Keys

May 2010 Room Keys Standard Room Keys Kansas – Prairie Band Casino Mfr: None Contributor: Esther Barker Louisiana, Harrah’s Mfr: None Contributor: Esther Barker Nevada – Caesar’s Palace Garden of the Gods Pool Oasis / Fortuna Pool Mfr: None Contributor: Esther Barker May 2010 Room Keys Nevada – Casino Fandango (a Courtyard by Marriott property) Front of key advertises Galaxy Theaters and 4 Great Restaurants Mfr: PL1 Contributor: Esther Barker Nevada – Circus Circus, Reno New Six great dining choices Mfr: None Contributor: Esther Barker Nevada – Circus Circus, Reno New Jackpot key Mfr: None Contributor: Esther Barker May 2010 Room Keys Nevada – Golden Nugget, Las Vegas New CH key Mfr: None Contributor: Esther Barker Nevada – Grand Sierra, Reno Charlie Palmer Steak Restaurant – grandsierra.com on reverse is 21.5 mm long (previous was 20.5 mm) I can’t believe no one caught my mistake last month (I said the web address was 63 mm long and something that long won’t fit on a skinny key) Mfr: None Contributor: Esther Barker Nevada – Grand Sierra, Reno Xtreme Sports Bar - Lounge Mfr: None Contributor: Esther Barker May 2010 Room Keys Nevada – Hooters New key replaces generic key issued recently Mfr: ILCO Contributor: Esther Barker Nevada – MGM Grand David Copperfield key Mfr: None Contributor: Esther Barker Nevada – MGM Grand Mayweather vs. Mosley key Mfr: None Contributor: Esther Barker May 2010 Room Keys Nevada – The Palazzo Azure key with “flat” blue strip at the bottom (glittery blue strip was listed last month) Mfr: None Contributor: Esther Barker Nevada – The Palazzo New “PRESTIGE” key, “Your key does more than open doors” “It gives you access and amenities only granted to the select few”.