Rāgas of the Kathmandu Valley: the Change in Meaning and Purpose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nepal Side, We Must Mention Prof

The Journal of Newar Studies Swayambhv, Ifliihichaitya Number - 2 NS 1119 (TheJournal Of Newar Studies) NUmkL2 U19fi99&99 It has ken a great pleasure bringing out the second issue of EdltLlo the journal d Newar Studies lijiiiina'. We would like to thank Daya R Sha a Gauriehankar Marw&~r Ph.D all the members an bers for their encouraging comments and financial support. ivc csp~iilly:-l*-. urank Prof. Uma Shrestha, Western Prof.- Todd ttwria Oregon Univers~ty,who gave life to this journd while it was still in its embryonic stage. From the Nepal side, we must mention Prof. Tej Shta Sudip Sbakya Ratna Kanskar, Mr. Ram Shakya and Mr. Labha Ram Tuladhar who helped us in so many ways. Due to our wish to publish the first issue of the journal on the Sd Fl~ternatioaalNepal Rh&a levi occasion of New Nepal Samht Year day {Mhapujii), we mhed at the (INBSS) Pdand. Orcgon USA last minute and spent less time in careful editing. Our computer Nepfh %P Puch3h Amaica Orcgon Branch software caused us muble in converting the files fm various subrmttd formats into a unified format. We learn while we work. Constructive are welcome we try Daya R Shakya comments and will to incorporate - suggestions as much as we can. Atedew We have received an enormous st mount of comments, Uma Shrcdha P$.D.Gaurisbankar Manandhar PIID .-m -C-.. Lhwakar Mabajan, Jagadish B Mathema suggestions, appreciations and so forth, (pia IcleI to page 94) Puma Babndur Ranjht including some ~riousconcern abut whether or not this journal Rt&ld Rqmmtatieca should include languages other than English. -

Lumbini Buddhist University

Lumbini Buddhist University Course of Study M.A. in Theravada Buddhism Lumbini Buddhist University Office of the Dean Senepa, Kathmandu Nepal History of Buddhism M.A. Theravada Buddhism First Year Paper I-A Full Mark: 50 MATB 501 Teaching Hours: 75 Unit I : Introductory Background 15 1. Sources of History of Buddhism 2 Introduction of Janapada and Mahajanapadas of 5th century BC 3. Buddhism as religion and philosophy Unit II : Origin and Development of Buddhism 15 1. Life of Buddha from birth to Mahaparinirvan 2. Buddhist Councils 3. Introduction to Eighteen Nikayas 4. Rise of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism Unit III: Expansion of Buddhism in Asia 15 1. Expansion of Buddhism in South: a. Sri Lanka b. Myanmar c. Thailand d. Laos, e. Cambodia 2. Expansion of Buddhism in North a. China, b. Japan, c. Korea, d. Mongolia e. Tibet, Unit IV: Buddhist Learning Centres 15 1. Vihars as seat of Education Learning Centres (Early Vihar establishments) 2. Development of Learning Centres: 1 a. Taxila Nalanda, b. Vikramashila, c. Odantapuri, d. Jagadalla, e. Vallabi, etc. 3. Fall of Ancient Buddhist Learning Centre Unit IV: Revival of Buddhism in India in modern times 15 1 Social-Religious Movement during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. 2. Movement of the Untouchables in the twentieth century. 3. Revival of Buddhism in India with special reference to Angarika Dhaminapala, B.R. Ambedkar. Suggested Readings 1. Conze, Edward, A Short History of Buddhism, London: George Allen and Unwin, 1980. 2. Dhammika, Ven. S., The Edicts of King Ashoka, Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society, 1994. 3. Dharmananda, K. -

PDF Generated By

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Dec 07 2015, NEWGEN 3 Vajrayāna Traditions in Nepal Todd Lewis and Naresh Man Bajracarya Introduction The existence of tantric traditions in the Kathmandu Valley dates back at least a thousand years and has been integral to the Hindu– Buddhist civi- lization of the Newars, its indigenous people, until the present day. This chapter introduces what is known about the history of the tantric Buddhist tradition there, then presents an analysis of its development in the pre- modern era during the Malla period (1200–1768 ce), and then charts changes under Shah rule (1769–2007). We then sketch Newar Vajrayāna Buddhism’s current characteristics, its leading tantric masters,1 and efforts in recent decades to revitalize it among Newar practitioners. This portrait,2 especially its history of Newar Buddhism, cannot yet be more than tentative in many places, since scholarship has not even adequately documented the textual and epigraphic sources, much less analyzed them systematically.3 The epigraphic record includes over a thousand inscrip- tions, the earliest dating back to 464 ce, tens of thousands of manuscripts, the earliest dating back to 998 ce, as well as the myriad cultural traditions related to them, from art and architecture, to music and ritual. The religious traditions still practiced by the Newars of the Kathmandu Valley represent a unique, continuing survival of Indic religions, including Mahāyāna- Vajrayāna forms of Buddhism (Lienhard 1984; Gellner 1992). Rivaling in historical importance the Sanskrit texts in Nepal’s libraries that informed the Western “discovery” of Buddhism in the nineteenth century (Hodgson 1868; Levi 1905– 1908; Locke 1980, 1985), Newar Vajrayāna acprof-9780199763689.indd 872C28B.1F1 Master Template has been finalized on 19- 02- 2015 12/7/2015 6:28:54 PM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Dec 07 2015, NEWGEN 88 TanTric TradiTions in Transmission and TranslaTion tradition in the Kathmandu Valley preserves a rich legacy of vernacular texts, rituals, and institutions. -

The Journey of Nepal Bhasa from Decline to Revitalization — Resha Maharjan Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies May 2018

Center for Sami Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Science and Education The Journey of Nepal Bhasa From Decline to Revitalization — Resha Maharjan Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies May 2018 The Journey of Nepal Bhasa From Decline to Revitalization A thesis submitted by Resha Maharjan Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies The Centre of Sami Studies (SESAM) Faculty of Humanities, Social Science and Education UIT The Arctic University of Norway May 2018 Dedicated to My grandma, Nani Maya Dangol & My children, Prathamesh and Pranavi मा車भाय् झीगु म्हसिका ख: (Ma Bhay Jhigu Mhasika Kha) ‘MOTHER TONGUE IS OUR IDENTITY’ Cover Photo: A boy trying to spin the prayer wheels behind the Harati temple, Swoyambhu. The mantra Om Mane Padme Hum in these prayer wheels are written in Ranjana lipi. The boy in the photo is wearing the traditional Newari dress. Model: Master Prathamesh Prakash Shrestha Photo courtesy: Er. Rashil Maharjan I ABSTRACT Nepal Bhasa is a rich and highly developed language with a vast literature in both ancient and modern times. It is the language of Newar, mostly local inhabitant of Kathmandu. The once administrative language, Nepal Bhasa has been replaced by Nepali (Khas) language and has a limited area where it can be used. The language has faced almost 100 years of suppression and now is listed in the definitely endangered language list of UNESCO. Various revitalization programs have been brought up, but with limited success. This main goal of this thesis on Nepal Bhasa is to find the actual reason behind the fall of this language and hesitation of the people who know Nepal Bhasa to use it. -

Ritual Period: a Comparative Study of Three Newar Buddhist Menarche Manuals Christoph Emmricha a University of Toronto, Canada Published Online: 27 Mar 2014

This article was downloaded by: [Christoph Emmrich] On: 14 April 2014, At: 13:57 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/csas20 Ritual Period: A Comparative Study of Three Newar Buddhist Menarche Manuals Christoph Emmricha a University of Toronto, Canada Published online: 27 Mar 2014. To cite this article: Christoph Emmrich (2014) Ritual Period: A Comparative Study of Three Newar Buddhist Menarche Manuals, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 37:1, 80-103, DOI: 10.1080/00856401.2014.873109 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00856401.2014.873109 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

NRNA Nepal Promotion Committee Overview

NRNA Nepal Promotion Committee Overview Nepal is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is located mainly in the Himalayas but also includes parts of the Indo-Gangetic Plain. With an estimated population of 29.4 million, it is 48th largest country by population and 93rd largest country by area.[2][14] It borders China in the north and India in the south, east, and west. Nepal has a diverse geography, including fertile plains, subalpine forested hills, and eight of the world's ten tallest mountains, including Mount Everest, the highest point on Earth. Kathmandu is the nation's capital and largest city. The name "Nepal" is first recorded in texts from the Vedic Age, the era in which Hinduism was founded, the predominant religion of the country. In the middle of the first millennium BCE, Gautama Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, was born in southern Nepal. Parts of northern Nepal were intertwined with the culture of Tibet. The centrally located Kathmandu Valley was the seat of the prosperous Newar confederacy known as Nepal Mandala. The Himalayan branch of the ancient Silk Road was dominated by the valley's traders. The cosmopolitan region developed distinct traditional art and architecture. By the 18th century, the Gorkha Kingdom achieved the unification of Nepal. The Shah dynasty established the Kingdom of Nepal and later formed an alliance with the British Empire, under its Rana dynasty of premiers. The country was never colonised but served as a buffer state between Imperial China and colonial India. Parliamentary democracy was introduced in 1951, but was twice suspended by Nepalese monarchs, in 1960 and 2005. -

The Guthi System of Nepal

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2019 The Guthi System of Nepal Tucker Scott SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, East Asian Languages and Societies Commons, Land Use Law Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Scott, Tucker, "The Guthi System of Nepal" (2019). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 3182. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/3182 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Guthi System of Nepal Tucker Scott Academic Director: Suman Pant Advisors: Suman Pant, Manohari Upadhyaya Vanderbilt University Public Policy Studies South Asia, Nepal, Kathmandu Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Nepal: Development and Social Change, SIT Study Abroad Spring 2019 and in fulfillment of the Capstone requirement for the Vanderbilt Public Policy Studies Major Abstract The purpose of this research is to understand the role of the guthi system in Nepali society, the relationship of the guthi land tenure system with Newari guthi, and the effect of modern society and technology on the ability of the guthi system to maintain and preserve tangible and intangible cultural heritage in Nepal. -

NEWAR ARCHITECTURE the Typology of the Malla Period Monuments of the Kathmandu Valley

BBarbaraarbara Gmińska-NowakGmińska-Nowak Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń Polish Institute of World Art Studies NEWAR ARCHITECTURE The typology of the Malla period monuments of the Kathmandu Valley INTRODUCTION: NEPAL AND THE KATHMANDU VALLEY epal is a country with an old culture steeped in deeply ingrained tradi- tion. Political, trade and dynastic relations with both neighbours – NIndia and Tibet, have been intense for hundreds of years. The most important of the smaller states existing in the current territorial borders of Nepal is that of the Kathmandu Valley. This valley has been one of the most important points on the main trade route between India and Tibet. Until the late 18t century, the wealth of the Kathmandu Valley reflected in the golden roofs of numerous temples and the monastic structures adorned by artistic bronze and stone sculptures, woodcarving and paintings was mainly gained from commerce. Being the point of intersection of significant trans-Himalaya trade routes, the Kathmandu Valley was a centre for cultural exchange and a place often frequented by Hindu and Buddhist teachers, scientists, poets, architects and sculptors.1) The Kathmandu Valley with its main cities of Kathmandu, Patan and Bhak- tapur is situated in the northeast of Nepal at an average height of 1350 metres above sea level. Today it is still the administrative, cultural and historical centre of Nepal. South of the valley lies a mountain range of moderate height whereas the lofty peaks of the Himalayas are visible in the North. 1) Dębicki (1981: 11 – 14). 10 Barbara Gmińska-Nowak The main group of inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley are the Newars, an ancient and high organised ethnic group very conscious of its identity. -

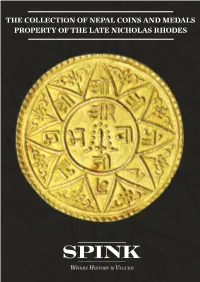

The Collection of Nepal Coins and Medals Property Of

THE COLLECTION OF NEPAL COINS AND MEDALS PROPERTY OF THE LATE NICHOLAS RHODES THE COLLECTION OF NEPALI COINS AND MEDALS PROPERTY OF THE LATE NICHOLAS RHODES THE COLLECTION OF NEPALI COINS AND MEDALS PROPERTY OF THE LATE NICHOLAS RHODES Nicholas Rhodes (1946-2011) has been described as a “numismatic giant … a scholar and collector of immense importance” (JONS No.208). His specialist numismatic interests embraced the currency of the whole Himalayan region - from Kashmir and Ladakh in the west, through Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan, to Assam and the Hindu states of north-east India. He was elected Honorary Fellow of the Royal Numismatic Society in 2002 and served as Secretary General of the Oriental Numismatic Society from 1997. Having started collecting coins from an early age, his lifelong passion for oriental coins started in 1962 with the coins of Nepal, which at the time presented the opportunity to build a meaningful collection and provided a fertile field for original research. ‘The Coinage of Nepal’, written in collaboration with close friends Carlo Valdettaro and Dr. Karl Gabrisch and published by the Royal Numismatic Society in 1989 (henceforth referred to in this brochure as ‘RGV’), is the standard reference work for this eye-catching series and “may be considered as Nicholas Rhodes’ magnum opus” (JONS No.208). The Nicholas Rhodes collection is considered to be the finest collection of Nepal coins currently in existence. Totalling approximately 3500 pieces, the collection is well documented and comprehensive; indeed, Nicholas was renowned for his painstaking ability to track down every known variety of a series. On the one hand it includes some magnificent highlights of the greatest rarity. -

Book Reviews

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 3 Number 2 Article 11 1983 Book Reviews Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation . 1983. Book Reviews. HIMALAYA 3(2). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol3/iss2/11 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VU. REVIEWS Slusser, Mar y Shepherd. Nepal Mandala- A Cultural Study of the Kathmandu Valley. 2 Vols . Princeton: 1982 Princeton University Press. Maps, dra wings and plans, 1 color plate, 600 bla ck and white plates,appendices, bibliogra phy, index. xix, 491 pp. $1 25.00 Reviewed by : Ronald M. Bernier University of Colorado In plate 500 of this long-awaited study, Dipankara Buddha is shown by Mary Shepherd Slusser in the form of an over life-sized portable sculpture and "mask," with man inside, walking down a Bhaktapur street at the time of the Panch- dan festival. Like this remarkable photograph, Nepal Mandala, the product of nearly 15 years of research in Nepal, presents works of art and architecture in the full context of human life, land, and time. It is a precisely documented reference work and a remarkable account of history, but it is also a lively study that brings together the earthly and heavenly occupants of the Nepalese universe. -

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: a Newar Perspective

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: A Newar Perspective A Dissertation Submitted to the University of Tsukuba In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Public Policy Suwarn VAJRACHARYA 2014 To my mother, who taught me the value in a mother tongue and my father, who shared the virtue of empathy. ii Map-1: Original Nepal (Constituted of 12 districts) and Present Nepal iii Map-2: Nepal Mandala (Original Nepal demarcated by Mandalas) iv Map-3: Gorkha Nepal Expansion (1795-1816) v Map-4: Present Nepal by Ecological Zones (Mountain, Hill and Tarai zones) vi Map-5: Nepal by Language Families vii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents viii List of Maps and Tables xiv Acknowledgements xv Acronyms and Abbreviations xix INTRODUCTION Research Objectives 1 Research Background 2 Research Questions 5 Research Methodology 5 Significance of the Study 6 Organization of Study 7 PART I NATIONALISM AND LANGUAGE POLITICS: VICTIMS OF HISTORY 10 CHAPTER ONE NEPAL: A REFLECTION OF UNITY IN DIVERSITY 1.1. Topography: A Unique Variety 11 1.2. Cultural Pluralism 13 1.3. Religiousness of People and the State 16 1.4. Linguistic Reality, ‘Official’ and ‘National’ Languages 17 CHAPTER TWO THE NEWAR: AN ACCOUNT OF AUTHORS & VICTIMS OF THEIR HISTORY 2.1. The Newar as Authors of their history 24 2.1.1. Definition of Nepal and Newar 25 2.1.2. Nepal Mandala and Nepal 27 Territory of Nepal Mandala 28 viii 2.1.3. The Newar as a Nation: Conglomeration of Diverse People 29 2.1.4. -

Viṣṇuitische Heiligtümer Und Feste Im Kathmandu-Tal/Nepal

Viṣṇuitische Heiligtümer und Feste im Kathmandu-Tal/Nepal Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt am 01. Juni 2007 von Kathleen Gögge Erstgutachter: Prof. Axel Michaels, Klassische Indologie, SAI Zweitgutachter: Apl. Prof. Ute Hüsken, Klassische Indologie, SAI Inhaltverzeichnis Verzeichnis der Abbildungen . v Verzeichnis der Karten . viii Verzeichnis der Tabellen . ix Vorwort . 1 Danksagung . 8 Abkürzungen . 10 1. Einleitung . 11 1.1. Geschichte Nepals . 11 1.2. Das viṣṇuitische Pantheon . 17 2. Die Vier-Nārāyaṇa-Heiligtümer des Kathmandu-Tals . 28 2.1. Einleitung . 28 2.1.1. Die Errichtung der Vier-Nārāyaṇa-Heiligtümer nach Inschriften und Chroniken . 28 2.1.2. Die Identifikation der Vier-Nārāyaṇa-Heiligtümer . 33 2.1.3. Die Anordnung der Vier-Nārāyaṇa-Heiligtümer in einem maṇḍala . 39 2.1.4. Die Übernahme von Kultstätten aus vorhinduistischer Zeit . 42 2.1.5. Topographie . 43 2.2. Der Cāṃgunārāyaṇa-Tempel . 46 2.2.1. Der Cāṃgunārāyaṇa-Tempel in der purāṇischen Literatur Nepals . 47 2.2.2. Beschreibung des Cāṃgunārāyaṇa-Tempelkomplexes . 52 2.2.3. Renovierungsmaßnahmen und Stiftungen . 60 2.2.4. Organisation und Ritualhandlungen . 70 2.2.5. Resümee . 79 2.3. Das Viśaṅkhunārāyaṇa-Heiligtum . 82 2.3.1. Beschreibung des Viśaṅkhunārāyaṇa-Heiligtums . 82 2.3.2. Ursprungsmythen . 84 2.3.3. Organisation und Ritualhandlungen . 87 2.3.4. Resümee . 89 2.4. Der Śikhara- oder Ṣeśanārāyaṇa-Tempel . 90 2.4.1. Der Standort in den Chroniken und in der purāṇischen Literatur Nepals 90 2.4.2. Historischer Hintergrund . 92 2.4.3. Beschreibung des Śikharanārāyaṇa-Tempelkomplexes . 93 2.4.4. Organisation und Ritualhandlungen . 98 2.4.5.