Operation Dixie and a Legacy of Worker Activism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PARTY WILL CEI2,BRTE SCHOOL's Hth ANNIVERSARY NINE ILR

November 4, 1949 Vol. II, No. 7 • FOR OUR INFORMATION F.O.I. appears bi-weekly from the Public Relations Office, Room 7, for the infor- mation of all faculty, staff and students of the New York State School orIndustrial and Labor Relations, Cornell University. A report of the Joint Legislative Committee on Industrial and Labor Conditions states, "The most satisfactory human relationships are the product, not of legal compulsion, but rather of voluntary determination among human beings to cooperate with one another." In the same spirit, F.O.I. is dedicated to our mutual understanding. EVERYONE INVITED TO ILR "OLD FASHIONED ELECTION PARTY" TUESDAY EVENING, NOV. 8; PARTY WILL CEI2,BRTE SCHOOLS hTH ANNIVERSARY Members of the faculty, staff and student body of the ILR School are invited to an Old Fashioned Election Night Party on Tuesday, November 8, in the Ivy Room of Willard Straight. The party is being given by the faculty, graduate students, and staff for undergraduate students of the ILR School. Husbands and wives are invited and all are urged to come and wear clothes suitable for square dancing. The fun will begin at 8:00 P.M. Refreshments, square dancing, election returns, a floor show, and other entertainment will be provided. Chairman of the Steering Committee for the party isLeane Eckert, Research Associate. NINE ILR STUDENTS ACTIVE ON GRIDIRON ILR School can be proud of its nine representatives on the football grid- iron this fall. Three ILR students are on the varsity team, three on the junior varsity, and three in the Big Red Band. -

Judge Jonathan Langham and the Use of the Labor Injunction in Indiana County, 1919-1931

Judge Jonathan Langham and the Use of the Labor Injunction in Indiana County, 1919-1931 ONATHAN LANGHAM, WHO SERVED AS JUDGE of the Court of Common Pleas of Indiana County, Pennsylvania, from 1916 to 1936, shaped political and economic developments locally and mirrored Jimportant elements on the national scene. His career on the bench was molded by his conservative Republican politics and his intimate connec- tions with the local political and business elite. Langham was born August 4, 1861, in Grant Township, Indiana County. He attended public school and graduated from Indiana Normal School in 1882. After teaching school for awhile he read law and was admitted to the bar in 1888. Langham held numerous political positions, including postmaster of Indiana and corporation deputy in the office of the auditor general of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Most impressive, however, was his congressional service. He represented the twenty-seventh District in the 61st, 62d, and 63d sessions of the U.S. House of Representatives. In 1915 he was elected judge of the Court of Common Pleas of Indiana County and won reelection to a second ten-year term in 1925.1 During the 1920s Langham used his judicial power to aid coal compa- nies in their battles against striking miners and the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). His blanket injunction during the Rossiter Coal Strike of 1927-28 brought him national attention and further polarized the responses to his rulings. Judge Langham's activities had national parallels as the federal judiciary joined with other branches of the govern- ment in supporting the reign of big business. -

Youngstown State University Oral History Program

YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM 1952 Youngstown Sheet & Tube Steel Strike Personal Experience O.H. 1218 RUSSELL L. THOMAS Interviewed by Andrew Russ on October 28, 1988 Russell Thomas resides in North Jackson, Ohio and was born on January 18, 1908 in East Palestine, Ohio. He attended high school in Coitsville, Ohio and eventually was employed for the United Steel Workers of America in the capacity of local union representative. Tn this capacity, he worked closely with the Youngstown's local steel workers' unions. It was from this position that he experienced the steel strike of 1952. Mr. Thomas, after relating his biography, went on to discuss the organization of the Youngstown contingent of the United Steel Workers of America. He went into depth into the union's genera- tion, it's struggle with management, and the rights it obtained for the average worker employed in the various steel mills of Youngstown. He recollected that the steel strike of 1952 was one that was different in the respect that President Truman had taken over the operation of the mills in order to prosecute the Korean War effort. He also discussed local labor politics as he had run for the posiUon of local union president. Although he was unsuccessful in this bid for office, his account of just how the local labor political game was played provided great insight into the labor movement's influence upon economic issues and public opinion. His interview was different in that it discussed not only particular issues that affected the average Youngstown worker employed in steel, but also broad political and economic ones that molded this period of American labor history. -

The Progressive Miners of America: Roots of Dissent and Foundational Years, 1932-1940

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2019 The Progressive Miners of America: Roots of Dissent and Foundational Years, 1932-1940 Ian Stewart Cook [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Cook, Ian Stewart, "The Progressive Miners of America: Roots of Dissent and Foundational Years, 1932-1940" (2019). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4082. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4082 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Progressive Miners of America: Roots of Dissent and Foundational Years, 1932-1940 Ian Cook Thesis submitted to the College of Eberly Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History in American Twentieth Century Ken Fones-Wolf, Ph.D., Chair Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D. William Gorby, Ph.D. Department of History Morgantown, West Virginia 2019 Keywords: Progressive Miners of America, Illinois, Coal Mining, United Mine Workers, John L. -

Experiences of C.W. Editor in Steel Towns with C.I.O

Experiences of C.W. Editor in Steel Towns with C.I.O. Dorothy Day The Catholic Worker, August 1936, 1, 2. *Summary: Impressions from a fact-finding tour of Pennsylvania steel towns and interviews with such figures as Bishop Boyle of Pittsburgh; John L. Lewis, chairman of the CIO; Kathryn Lewis, his daughter; and John Brophy, Director of the CIO. For readers seeking background information on the steel/labor struggle, she recommends several books. Applauds church and government efforts to support labor in its struggle to organize and notes with satisfaction The CW ’s ability to transcend race and ethnic boundaries. Keywords: labor, unions, social teaching (DDLW #302).* A story like this is too big to compress in one column. Impressions crowded upon one over two weeks of constant observation are hard to put down on paper. There could be an interview with Bishop Boyle of Pittsburgh; with John L. Lewis, chairman of the Committee on Industrial Organization; with John Brophy, director of the committee; with Philip Murray, head of the Steel Workers’ Organization Committee (SWOC); with Pat Fagin, president of District No. 5 of the United Mine Workers; with the wives and mothers of steel workers; with Father Kazincy, who spoke from a wooden platform out in an open air mass meeting at Braddock last Sunday; with Smiley Chatak, the young organizer of the Allegheny Valley; with the Slovaks, the Croatians, the Syrians, the Italians and the Americans I have been seeing this past month–individuals among the 500,000 steel workers who have been unorganized, oppressed and enslaved for the last half century in the giant mills of the American Iron and Steel Institute. -

The Rise of the Pension and Social Insurance Program of the United Steelworkers of America, 1941-1960

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2019 Bargaining for Security: The Rise of the Pension and Social Insurance Program of the United Steelworkers of America, 1941-1960 Henry Edward Himes III [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Labor History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Himes, Henry Edward III, "Bargaining for Security: The Rise of the Pension and Social Insurance Program of the United Steelworkers of America, 1941-1960" (2019). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 3917. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/3917 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bargaining for Security: The Rise of the Pension and Social Insurance Program of the United Steelworkers of America, 1941-1960 Henry E. Himes III Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Ken Fones-Wolf, PhD., Chair Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, PhD. -

How Labor Won and Lost the Public in Postwar America, 1947-1959

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2014 The Fight Over John Q: How Labor Won and Lost the Public in Postwar America, 1947-1959 Rachel Burstein Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/179 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Fight Over John Q: How Labor Won and Lost the Public in Postwar America, 1947-1959 by Rachel Burstein A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 Rachel Burstein All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. __________________ _______________________________________ Date Joshua Freeman, Chair of Examining Committee __________________ _______________________________________ Date Helena Rosenblatt, Executive Officer Joshua Brown Thomas Kessner David Nasaw Clarence Taylor Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract The Fight Over John Q: How Labor Won and Lost the Public in Postwar America, 1947-1959 by Rachel Burstein Adviser: Joshua Freeman This study examines the infancy of large-scale, coordinated public relations by organized labor in the postwar period. Labor leaders’ outreach to diverse publics became a key feature of unions’ growing political involvement and marked a departure from the past when unions used organized workers – not the larger public – to pressure legislators. -

ABSTRACT CARVER, MARK DEAN. The

ABSTRACT CARVER, MARK DEAN. The Unionization of Erwin’s Mill: A History of TWUA Local 250, in Erwin, North Carolina: 1938-1952 (Under the direction of David Zonderman) The purpose of this study is to document the history of the Textile Workers union of America (TWUA), Local 250, in Erwin, North Carolina, from 1938-1952. Prior to unionization, Erwin’s workers suffered unfair labor practices including: heavy workloads, low wages, long hours, and the absence of grievance procedure. The unionization of Erwin’s workers provided a grievance procedure, fair workloads, higher wages, and better hours. TWUA Local 250 worked hard to represent its members and assure them a fair and just system. This thesis examines the first fifteen years of unionization and some of the problems that occurred in Erwin’s mill. These problems include anti-union sentiment, unfair company policies, an unnecessary strike, and a political power struggle within the national union. Through the examination of primary sources including company, union, government correspondences, newspaper articles, and personal interviews, it becomes evident that Erwin’s workers needed a union to ensure a fair and just system. A fair and just system would only be possible through better communication with the company, the national union, and the federal government. The company, national union, and government seemed to care very little for the desperate situations endured by Local 250 during these first fifteen years. This thesis shows the national union’s poor judgment, lack of leadership, and most of all, lack of compassion for Local 250. This study provides a view of the national union from the perspective of the local union. -

The AFL-CIO Approaches the Vietnam War, 1947-64

LaborHistory, Vol. 42, No. 3, 2001 “NoMore Pressing Task than Organization in Southeast Asia”: TheAFL– CIO Approaches the VietnamWar, 1947– 64 EDMUNDF. WEHRLE* The Vietnam War standsas the most controversial episodein theAFL– CIO’ s four decadesof existence.The federation’s supportfor thewar dividedits membership and drovea wedgebetween organized labor andits liberal allies. By theearly 1970s, the AFL–CIO wasa weakenedand divided force, ill-prepared for adecadeof economic decline.Few, however, recognize thecomplex rootsof the federation’ s Vietnam policy. American organized labor, in fact,was involved deeplyin Vietnam well beforethe American interventionin 1965. In SoutheastAsia, it pursuedits ownseparate agenda, centeredon support for asubstantial SouthVietnamese trade unionmovement under theleadership ofnationalist Tran QuocBuu. 1 Yet,as proved tobe the case for labor throughout thepost-World War IIperiod,its plans for SouthVietnam remained very muchcontingent on its relationship with the U.S.state. This oftenstrained but necessary partnership circumscribedand ultimately crippled thefederation’ s independentplans for Vietnameselabor. Trade unionistsin SouthVietnam foundthemselves in asimilar, although more fatal, bind,seeking to act independently,yet boundto the Americans anda repressiveSouth Vietnamese state. Scholars today oftenportray post-warAmerican organized labor asa partner (usually acompliant juniorpartner) in an accordor corporate arrangement with other “functionalgroups” including thestate and business. 2 While thereis undeniabletruth -

The Automobile Workers Unions and the Fight for Labor Parties in the 1930S

The Automobile Workers Unions and the Fight for Labor Parties in the 1930s Hugh T. Louin* Despite the New Dealers’ innovative social and economic programs during the 1930s, discontented agrarians and labor unionists judged the New Deal’s shortcomings so severe that they began to nurture third party movements. Scrappy auto- mobile industry unionists in Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana at first ignored the new third party efforts of impatient New Deal critics. Instead, with many other organized and unorganized workers, they expected New Dealers to provide better times after the “lean years” of the 1920s. During the post-World War I decade union rolls had declined, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) had lost prestige, and unions had exercised little influence with lawmakers and other elected officials. Conse- quently, employers easily avoided collective bargaining with unions, strikes often were ineffective, and unionists charged that public officials consistently deployed police forces and the National Guard to tilt the balance in industry’s favor during labor-management conflicts.’ The New Dealers of the 1930s, although clearly pro-labor, failed to effect many of the changes which automobile industry workers anticipated. In response, disgruntled automobile union- ists in the Great Lakes states attempted to build labor parties. That they failed to create viable labor parties calls attention to the remarkable resiliency of America’s two party system even during the nation’s most severe depression. More important, the unionists’ failures to establish labor parties reflect the New Deal’s hold on so many industrial workers and AFL craft un- * Hugh T. hvin is professor of history at Boise State University, Boise, Idaho. -

John Brophy Manuscript Group 40

Special Collections and University Archives John Brophy Manuscript Group 40 For Scholarly Use Only Last Modified October 2, 2014 Indiana University of Pennsylvania 302 Stapleton Library Indiana, PA 15705-1096 Voice: (724) 357-3039 Fax: (724) 357-4891 Manuscript Group 40 2 John Brophy, Manuscript Group 40 Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Special Collections and University Archives 1 box; 0.5 linear feet Biographical Note Throughout his life, John Brophy (November 6, 1883 – February 19, 1963) supported organized labor as a miner, union activist, and union official. He was born in Lancashire in northwest England to a family of coal miners. As a youngster in 1892, he emigrated from England to the United States with his parents. The Brophy family immediately found work in the central Pennsylvania coal mines. Before he turned 12, young John Brophy began working in the mines. Raised by a union supporting coal miner, John Brophy entered the mines with his father in 1894, and joined the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) in 1899. An activist in the union, he was elected president of UMWA District 2, representing Central Pennsylvania, in 1916. As a member of the Nationalization Research Committee in the early 1920s he vigorously supported the nationalization of the mining industry. As a checkweighman, local officer, and finally as president of District 2 of the UMWA, he served the miners of Pennsylvania. During the 1920s, John Brophy became the leader of the opposition movement in the UMWA. Brophy maintained his position as President of UMWA District 2 until 1926 when he challenged John L. -

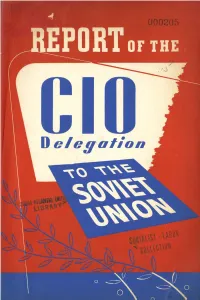

Soviet Union

REPORT of the CIO DELEGATION to the SOVIET UNION Submitted by JAMES B. CAREY Secretary-Treasurer, CIO Chairman of the Delegation Other Members of the Delegation: JOSEPH CURRAN REID ROBINSON rice-President, CIO Fice-P resident , CIO President, N at ional M arit ime Union President , Lnt crnational Union of .lIint', J / ill and Smelt er Il'orkers ALBERTJ . FITZGERALD r ice-Pre siden t, CIO LEE PRESSMAN President , Un ited E lect rical, R adio and General Couusrl, c/o JIacliine W orkers 0/ .Inisr ica JOHN GREEN JOHN ABT rice-President, CIO General Cou nsel, Amalgamat ed Clot hing President, Indust rial Union 0/ M an ne and W orku 5 0/ .lmeri ca Sh ipb uilding W orlecrs LEN DE CAUX ALLAN S. HAYWOOD Pu blicit y D irect or, CIO, and E dit or, Tilt' Fice -President, CIO C/O N m 's D irector 0/ Organization, CIO EMIL RIEVE VINCENT SWEENEY r ia-President, CIO Pu blicit y D irect or, United St rrlzcorlerrs President, T ext ile W orkers Union oi A merica 0/ A merica; Editor, St eel Labor Publication No. 128 Price 15c per copy; 100 for $10.00; 500 for $40.00 D epartment of International Affairs Order Literature from Publicity Department CONGRESS OF INDUSTRIAL ORGANIZATIONS 718 JACKSON PLACE, N. W. WASHINGTON 6, D. C. \ -- . ~ 2 rr To Promote Friendship And Understanding... " H E victo ry of the United Nations over the military power of fascism T opened up prospects of a new era of int ern ational understanding, democratic progress, world peace and prosperity.