The Key to Success in Afghanistan a Modern Silk Road Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afghanistan National Railway Plan and Way Forward

Afghanistan National Railway Plan and Way Forward MOHAMMAD YAMMA SHAMS Director General & Chief Executive Officer Afghanistan Railway Authority Nov 2015 WHY RAILWAY IN AFGHANISTAN ? → The Potential → The Benefits • Affinity for Rail Transportation Pioneer Development of Modern – Primary solution for landlocked, Afghanistan developing countries/regions – At the heart of the CAREC and Become Part of the International ECO Program Rail Community – 75km of railroad vs 40,000 km of – Become long-term strategic partner road network to various countries – Rich in minerals and natural – Build international rail know-how resources – rail a more suitable (transfer of expertise) long term transportation solutions Raise Afghanistan's Profile as a than trucking. Transit Route • Country Shifting from Warzone – Penetrate neighbouring countries to Developing State Rail Market including China, Iran, Turkey and countries in Eastern – Improved connection to the Europe. community and the region (access – Standard Gauge has been assessed to neighbouring countries) as the preferred system gauge. – Building modern infrastructure – Dual gauge (Standard and Russian) in – Facilitate economic stability of North to connect with CIS countries modern Afghanistan STRATEGIC LOCATION OF AFGHANISTAN Kazakhstan China MISSING LINKS- and ASIAN RAILWAY TRANS-ASIAN RAILWAY NETWORK Buslovskaya St. Petersburg RUSSIAN FEDERATION Yekaterinburg Moscow Kotelnich Omsk Tayshet Petropavlovsk Novosibirsk R. F. Krasnoe Syzemka Tobol Ozinki Chita Irkutsk Lokot Astana Ulan-Ude Uralsk -

The Essence of Progress British and Afghan Troops Take on Insurgency In

Nawa: The essence of progress Story and photos by Marine Cpl. Jeff Drew CAMP LEATHERNECK, Helmand province, Afghanistan - Extensive improvements in Nawa district and exceptional Afghan leadership has transformed the once improvised explosive device-laden area into a peaceful paragon of progress during the last year. Residents walk casually along roads and waterways, confident in local Afghan security forces to keep them safe. The growth of illegal drugs has been nearly eradicated as citizens have begun to see the benefits of growing legal crops. Interest in education is on the rise, ensuring a brighter future for the people of Nawa. The people are happy, healthy and hopeful. "Over the past 30 years Nawa lost everything, but now the government system is active," said Haji Abdul Manaf, the district governor of Nawa. "There was no rule, but now there is; there was no education, but now there is; there was no security, but now there is; there were no human rights, but now there is; there was poppy, but now it has been eradicated. The people laid down their weapons, and there was peace." (Read the STORY) British and Afghan troops take on insurgency in Gereshk U.K. Defence News Nearly 1,000 British and Afghan soldiers have taken part in a major operation to increase security around a vital town in Helmand province. More than 280 British troops joined forces with 690 warriors from the Afghan National Army (ANA) and patrolmen from the Afghan National Police to clear insurgents from the area north of the bustling town of Gereshk in Nahr-e Saraj district. -

Here the Taleban Are Gaining Ground

Mathieu Lefèvre Local Defence in Afghanistan A review of government-backed initiatives EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Given events happening in Afghanistan and in the of the Government to provide stability and region, as well as domestic pressures building in strengthen development through community the United States and Europe regarding further security.’ A pilot project that started in Wardak in engagement in Afghanistan, decision makers are March 2009 is ongoing. To date 1,100 men – more under pressure to find new solutions to restore than the number of provincial police – have been security in large parts of the country. Against this recruited in Wardak, mainly through direct backdrop, the Afghan government and its patronage by elders, local power brokers and international supporters are giving in to a cyclical prominent jihadi commanders, bypassing the temptation of working with informal armed groups intended shura-based mechanism. Many of the to provide security, particularly in remote rural problems that had plagued the ANAP came back to areas where the Taleban are gaining ground. haunt AP3. The program has not been considered successful enough to replicate in other provinces The first initiative examined in this paper is the but a similar program (the Afghanistan Public Afghanistan National Auxiliary Police (ANAP), Protection Force) has been included in the overall launched by the Ministry of Interior with MoI police strategy. international support in 2006 to provide a ‘community policing’ function. Recruits were The most recent and most experimental of the selected, trained, armed, equipped and deployed three programs is the Local Defence Initiatives in provinces mainly in the south and southeast. -

Nimroz Rapid Drought Assessment Zaranj, Kang and Chakhansoor Districts Conducted August 21St-22Nd 2013

Nimroz Rapid Drought Assessment Zaranj, Kang and Chakhansoor Districts Conducted August 21st-22nd 2013 Figure 1 Dead livestock in Kang district Figure 2 Nimroz district map Relief International in Nimroz Relief International (RI) is a humanitarian, non‐profit, non‐sectarian agency that provides emergency relief, rehabilitation, and development interventions throughout the world. Since 2001, RI has supported a wide array of relief and development interventions throughout Afghanistan. RI programs focus on community participation, ensuring sustainability and helping communities establish a sense of ownership over all stages of the project cycle. Relief International has been working in Nimroz province since 2007, when RI took over implementation of the National Solidarity Program, as well as staff and offices, from Ockenden International. Through more than five years of work in partnership with Nimroz communities, RI has formed deep connections with communities, government, and other stakeholders such as UN agencies. RI has offices and is currently working in all districts of Nimroz, except for the newly added Delaram district (formerly belonging to Farah Province). RI has recently completed an ECHO WASH and shelter program and a DFID funded local governance program , and is currently implementing the National Solidarity Program and a food security and livelihoods program in the province. Nimroz General Information related to Drought Nimroz province is the most South Westerly Province of Afghanistan bordering Iran and Pakistan. The provincial capital is Zaranj, located in the west on the Iranian border. The population is estimated at 350,000 although, as for the rest of Afghanistan, no exact demographic data exists.1 There has been a flow of returnees from Iran over the last years, and the provincial capital has also grown due to internal migration. -

Länderinformationen Afghanistan Country

Staatendokumentation Country of Origin Information Afghanistan Country Report Security Situation (EN) from the COI-CMS Country of Origin Information – Content Management System Compiled on: 17.12.2020, version 3 This project was co-financed by the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund Disclaimer This product of the Country of Origin Information Department of the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum was prepared in conformity with the standards adopted by the Advisory Council of the COI Department and the methodology developed by the COI Department. A Country of Origin Information - Content Management System (COI-CMS) entry is a COI product drawn up in conformity with COI standards to satisfy the requirements of immigration and asylum procedures (regional directorates, initial reception centres, Federal Administrative Court) based on research of existing, credible and primarily publicly accessible information. The content of the COI-CMS provides a general view of the situation with respect to relevant facts in countries of origin or in EU Member States, independent of any given individual case. The content of the COI-CMS includes working translations of foreign-language sources. The content of the COI-CMS is intended for use by the target audience in the institutions tasked with asylum and immigration matters. Section 5, para 5, last sentence of the Act on the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (BFA-G) applies to them, i.e. it is as such not part of the country of origin information accessible to the general public. However, it becomes accessible to the party in question by being used in proceedings (party’s right to be heard, use in the decision letter) and to the general public by being used in the decision. -

Three Ports Under China's Gaze Kulshrestha, Sanatan

www.ssoar.info Three Ports Under China's Gaze Kulshrestha, Sanatan Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kulshrestha, S. (2017). Three Ports Under China's Gaze. IndraStra Global, 8, 1-7. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-53427-9 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. Three Ports Under China’s Gaze indrastra.com/2017/08/Three-Ports-Under-China-s-Gaze-003-08-2017-0050.html By Rear Admiral Dr. -

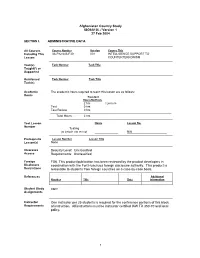

Appendix H- Afghanistan Overview Program of Instruction

Afghanistan Country Study ISO6A10L / Version 1 27 Feb 2004 SECTION I. ADMINISTRATIVE DATA All Courses Course Number Version Course Title Including This 3A-F82/243-F30 001 INTELLIGENCE SUPPORT TO Lesson COUNTERTERRORISM Task(s) Task Number Task Title Taught(*) or Supported Reinforced Task Number Task Title Task(s) Academic The academic hours required to teach this lesson are as follows: Hours Resident Hours/Methods 2 hrs / Lecture Test 0 hrs Test Review 0 hrs Total Hours: 2 hrs Test Lesson Hours Lesson No. Number Testing (to include test review) N/A Prerequisite Lesson Number Lesson Title Lesson(s) None Clearance Security Level: Unclassified Access Requirements: Unclassified Foreign FD6. This product/publication has been reviewed by the product developers in Disclosure coordination with the Fort Huachuca foreign disclosure authority. This product is Restrictions releasable to students from foreign countries on a case-by-case basis. References Additional Number Title Date Information Student Study none Assignments Instructor One instructor per 25 students is required for the conference portions of this block Requirements of instruction. All instructors must be instructor certified IAW TR 350-70 and local policy. 1 Additional Stu Support Name Ratio Qty Man Hours Personnel None Requirements Equipment Id Stu Instr Required Name Ratio Ratio Spt Qty Exp for Instruction 6730-01-T08-4239 25:1 1:25 No 1 No Projector LitePro * Before Id indicates a TADSS Materials Instructor Materials: Required Course Introduction, Lesson Plan, and Slideshow. Student Materials: Notebook and pen. Classroom, CLASSROOM, GEN INSTRUCTION, 1000 SQ FT, 30 PN Training Area, and Range Requirements Ammunition Stu Instr Spt Requirements Id Name Exp Ratio Ratio Qty None Instructional NOTE: Before presenting this lesson, instructors must thoroughly prepare by studying this Guidance lesson and identified reference material. -

India's and Pakistan's Strategies in Afghanistan : Implications for the United States and the Region / Larry Hanauer, Peter Chalk

CENTER FOR ASIA PACIFIC POLICY International Programs at RAND CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and EDUCATION AND THE ARTS decisionmaking through research and analysis. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from www.rand.org as a public service INFRASTRUCTURE AND of the RAND Corporation. TRANSPORTATION INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY Support RAND SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Purchase this document TERRORISM AND Browse Reports & Bookstore HOMELAND SECURITY Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Center for Asia Pacific Policy View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation occasional paper series. RAND occa- sional papers may include an informed perspective on a timely policy issue, a discussion of new research methodologies, essays, a paper presented at a conference, a conference summary, or a summary of work in progress. All RAND occasional papers undergo rigorous peer review to ensure that they meet high standards for research quality and objectivity. -

Chairperson, Ladies and Gentlemen

Chairperson, ladies and gentlemen: It is indeed a honor and my privilege to be amongst you on the the Fourth Meeting of the Working Group on the Asian Highway and Expert Group Meeting on Progress on the Road Safety Improvement in Asia and the Pasific,May I take this opportunity to convey the warm wishes of the Afghan people to the delegate attending this Session . On behalf of Gov. Islamic Republic of Afghanistan I would like to extend its strong support for the conference to implement Transport development in the region to strengthen sub regional cooperation in Asia and its integration into the world economy. The Govt of Afghanistan sees grater regional cooperation as critical for helping developing countries to reach their economic growth potential and for eradicating poverty in Asia. Afghanistan views Afghanistan remains committed to promote security, stability, peace and economic development in the region through cooperation with ESCAP member States on issues of mutual interest and mutual benefit. After decades of violence, destruction and instability, Afghanistan has successfully embarked upon the path of democracy and development since 2001. The long period of turmoil and violence has thrown challenges up for Afghanistan, which it cannot overcome all by itself. The cooperation of all nations, especially its neighbors and countries of the region is needed to overcome regional and global challenges. Many of the challenges being faced by Afghanistan like terrorism, narcotics, energy crisis, expediting socio-economic development etc are also of deep concern to all members of (ESCAP). Mutual cooperation is required to face these challenges easily and effectively 1. -

The Impact of Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and Central Asia

Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia June 26, 2012 i US AND IRANIAN STRATEGIC COMPETITION: The Impact of Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and Central Asia By Robert M. Shelala II, Nori Kasting, and Anthony H. Cordesman June 26, 2013 Anthony H. Cordesman Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy [email protected] Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia June 26, 2012 ii Acknowledgements Sam Khazai and Sean Mann made important contributions to this analysis. Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia June 26, 2012 iii Executive Summary Security and stability in Central and South Asia are driven by regional tensions and quarrels, and the internal instability of regional states. Weak governance and corruption are major problems in every state in the region, along with state barriers to economic growth and development and – in most cases – under investment in education, health, and infrastructure. Very young populations face major unemployment and underemployment problems and income distribution is badly unbalanced, and on sharply favors the ruling power elite. Ethic, tribal, and sectarian tensions compound these problems, and in many cases, so do internal and external threats from Islamic extremists and the growing tensions between Sunni and Shi‟ite. The tensions between the US and Iran have been peripheral to these forces and are likely to remain so – particularly since the US is largely leaving Afghanistan and has steadily declined strategic interest in Pakistan and Central Asia as well. The one exception that might sharply increase US and Iranian competition would be a contingency where a major confrontation or conflict between the US and Iran that began in the Gulf – or outside Central and South Asia – led Iran to be far more aggressive in attacking or challenge UDS interest in the region. -

An Agenda for US-India Cooperation in Afghanistan

AP PHOTO/GURINDER PHOTO/GURINDER AP O S A N Toward Convergence: An Agenda for U.S.-India Cooperation in Afghanistan C. Raja Mohan, Caroline Wadhams, Wilson John, Aryaman Bhatnagar, Daniel Rubin, and Peter Juul June 2013 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Toward Convergence: An Agenda for U.S.-India Cooperation in Afghanistan C. Raja Mohan, Caroline Wadhams, Wilson John, Aryaman Bhatnagar, Daniel Rubin, and Peter Juul June 2013 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 7 U.S. interests and policy in Afghanistan 13 India’s interests and strategy in Afghanistan 17 Afghanistan’s internal instabilities 21 Pakistan and its role in Afghanistan 25 Next steps: Toward enhanced U.S.-India cooperation in Afghanistan 35 Recommendations for U.S. and Indian policymakers 41 Conclusion 43 About the authors 45 Endnotes Introduction and summary As the United States reduces its military presence in Afghanistan and transfers secu- rity control to the Afghan government in 2014, the governments in New Delhi and Washington should find ways to strengthen their partnership in Afghanistan. At the same time, they should embed it in a sustainable structure of regional cooperation in order to ensure the future stability of Afghanistan. The United States and India share a number of objectives in Afghanistan and the wider region, including: • A unified and territorially integrated Afghanistan • A sovereign, independent, and functional Afghan government based on the principles underlying the current constitution, including democracy, nonviolent political competition, and basic human -

India in Afghanistan: Understanding Development Assistance by Emerging Donors to Conflict-Affected Countries

India in Afghanistan: Understanding Development Assistance by Emerging Donors to Conflict-Affected Countries Rani D. Mullen College of William & Mary1 Changing Landscape of Assistance to Conflict-Affected States: Emerging and Traditional Donors and Opportunities for Collaboration Policy Brief # 10 Policy brief series edited by Agnieszka Paczynska, School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution, George Mason University/Stimson Center August 2017 Introduction India is increasingly becoming an important donor also to conflict-affected countries. Indian development assistance is important to understand, since India is the world’s third largest economy in purchasing power parity terms (PPP), one of the fastest-growing countries in the world, and has an expanding development assistance program. In U.S. dollar terms, India’s foreign aid program is not as large as that of traditional donors or as large as that of other emerging donors such as its neighbor China. Yet, a purely dollar-focused comparison of Indian aid underestimates the comparative advantage of Indian aid, both in PPP terms, as well as in terms of cultural affinity and sustainability particularly for neighboring countries.2 Since the majority of traditional donors, such as the United States, distribute assistance through the donor country’s citizens and contractors, often using materials sourced from the donor country, a U.S. dollar (USD) of aid “buys” significantly less of American goods and services than does the U.S. dollar equivalent of aid from emerging donors such as India. As seen in figure 1, Indian aid (grants and loans) in 2015-16 totaled approximately USD 1.36 billion. Yet in PPP terms it totaled over USD 5 billion – equivalent to approximately USD 4.6 billion of Canadian aid and significantly more than the USD 2.76 billion ofAustralian aid during 2015 in PPP terms.3 Moreover, even the PPP estimates of Indian aid underestimate its value to the local recipient, particularly with regards to technical assistance and training.