India in Afghanistan: Understanding Development Assistance by Emerging Donors to Conflict-Affected Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afghanistan Review

1 01 December 2010 AFGHANISTAN REVIEW Inside This Issue Economic Stabilization This document is intended to provide an overview of relevant sector Governance & Participation events in Afghanistan from 23 November–30 November 2010. More Humanitarian Assistance comprehensive information is available on the Civil-Military Overview (CMO) at www.cimicweb.org. Hyperlinks to original source material Infrastructure are highlighted in blue and underlined in the embedded text. Justice & Reconciliation Security Social Well-Being For further information on CFC activities related to Afghanistan or inquiries about this publication, please contact the Afghanistan Team Manager: Valeria Davanzo, [email protected] or the Afghanistan Editor: Amber Ram- sey, [email protected] ECONOMIC STABILIZATION Steve Zyck, [email protected] / +1 757-683-4275 Back to top Mineral and energy deposits in Afghanistan were the ban was allegedly instituted as a result of the Af- subject of continued discussion this week. An official ghan government‟s failure to update its 1972 avia- from Afghanistan‟s Ministry of Mines (MoM) told Tolo tion regulations or establish a civil aviation author- News that oil deposits in northern Afghanistan would ity. According to Reuters, the ban affects Safi Air- be opened for tender by the end of the year. Offi- lines in particular, which is one of three Afghanistan cials say that oil deposits around Sheberghan, in -registered airlines to offer flights to Europe in re- Jowzjan province, and Qashqari, in Sar-e Pul prov- cent years. The EU's recent decision also served to ince, will likely be tendered first. Experts interviewed extend and expand previously-imposed restrictions by Tolo News have suggested that investor interest on Ariana Afghan Airlines and Kam Air, the two in Afghanistan‟s energy and mineral resources may other banned carriers. -

Afghanistan National Railway Plan and Way Forward

Afghanistan National Railway Plan and Way Forward MOHAMMAD YAMMA SHAMS Director General & Chief Executive Officer Afghanistan Railway Authority Nov 2015 WHY RAILWAY IN AFGHANISTAN ? → The Potential → The Benefits • Affinity for Rail Transportation Pioneer Development of Modern – Primary solution for landlocked, Afghanistan developing countries/regions – At the heart of the CAREC and Become Part of the International ECO Program Rail Community – 75km of railroad vs 40,000 km of – Become long-term strategic partner road network to various countries – Rich in minerals and natural – Build international rail know-how resources – rail a more suitable (transfer of expertise) long term transportation solutions Raise Afghanistan's Profile as a than trucking. Transit Route • Country Shifting from Warzone – Penetrate neighbouring countries to Developing State Rail Market including China, Iran, Turkey and countries in Eastern – Improved connection to the Europe. community and the region (access – Standard Gauge has been assessed to neighbouring countries) as the preferred system gauge. – Building modern infrastructure – Dual gauge (Standard and Russian) in – Facilitate economic stability of North to connect with CIS countries modern Afghanistan STRATEGIC LOCATION OF AFGHANISTAN Kazakhstan China MISSING LINKS- and ASIAN RAILWAY TRANS-ASIAN RAILWAY NETWORK Buslovskaya St. Petersburg RUSSIAN FEDERATION Yekaterinburg Moscow Kotelnich Omsk Tayshet Petropavlovsk Novosibirsk R. F. Krasnoe Syzemka Tobol Ozinki Chita Irkutsk Lokot Astana Ulan-Ude Uralsk -

Improving the Effectiveness of Australia's Bilateral Aid Program In

Improving the effectiveness of Australia’s bilateral aid program in Papua New Guinea: some analysis and suggestions A submission to the Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Reference Committee Stephen Howes1 1 Professor of Economics and Director, Development Policy Centre, Australian National University. This submission represents my opinions, and are not those of The Australian National University nor necessarily of any of my co-authors of works I cite. 1 Table of Contents Summary and recommendations............................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Part A: PNG, and aid to PNG ................................................................................................................... 7 A1. Papua New Guinea: an overview .................................................................................................. 7 A2. Global aid to Papua New Guinea ................................................................................................ 11 A3. Australian aid to PNG .................................................................................................................. 14 Part B: Cross-cutting issues ................................................................................................................... 23 B1. The need for greater consistency of approach .......................................................................... -

The Essence of Progress British and Afghan Troops Take on Insurgency In

Nawa: The essence of progress Story and photos by Marine Cpl. Jeff Drew CAMP LEATHERNECK, Helmand province, Afghanistan - Extensive improvements in Nawa district and exceptional Afghan leadership has transformed the once improvised explosive device-laden area into a peaceful paragon of progress during the last year. Residents walk casually along roads and waterways, confident in local Afghan security forces to keep them safe. The growth of illegal drugs has been nearly eradicated as citizens have begun to see the benefits of growing legal crops. Interest in education is on the rise, ensuring a brighter future for the people of Nawa. The people are happy, healthy and hopeful. "Over the past 30 years Nawa lost everything, but now the government system is active," said Haji Abdul Manaf, the district governor of Nawa. "There was no rule, but now there is; there was no education, but now there is; there was no security, but now there is; there were no human rights, but now there is; there was poppy, but now it has been eradicated. The people laid down their weapons, and there was peace." (Read the STORY) British and Afghan troops take on insurgency in Gereshk U.K. Defence News Nearly 1,000 British and Afghan soldiers have taken part in a major operation to increase security around a vital town in Helmand province. More than 280 British troops joined forces with 690 warriors from the Afghan National Army (ANA) and patrolmen from the Afghan National Police to clear insurgents from the area north of the bustling town of Gereshk in Nahr-e Saraj district. -

Here the Taleban Are Gaining Ground

Mathieu Lefèvre Local Defence in Afghanistan A review of government-backed initiatives EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Given events happening in Afghanistan and in the of the Government to provide stability and region, as well as domestic pressures building in strengthen development through community the United States and Europe regarding further security.’ A pilot project that started in Wardak in engagement in Afghanistan, decision makers are March 2009 is ongoing. To date 1,100 men – more under pressure to find new solutions to restore than the number of provincial police – have been security in large parts of the country. Against this recruited in Wardak, mainly through direct backdrop, the Afghan government and its patronage by elders, local power brokers and international supporters are giving in to a cyclical prominent jihadi commanders, bypassing the temptation of working with informal armed groups intended shura-based mechanism. Many of the to provide security, particularly in remote rural problems that had plagued the ANAP came back to areas where the Taleban are gaining ground. haunt AP3. The program has not been considered successful enough to replicate in other provinces The first initiative examined in this paper is the but a similar program (the Afghanistan Public Afghanistan National Auxiliary Police (ANAP), Protection Force) has been included in the overall launched by the Ministry of Interior with MoI police strategy. international support in 2006 to provide a ‘community policing’ function. Recruits were The most recent and most experimental of the selected, trained, armed, equipped and deployed three programs is the Local Defence Initiatives in provinces mainly in the south and southeast. -

Australia's Development Assistance Program

CHAPTER 8 AUSTRALIA'S DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE PROGRAM Introduction 8.1 Although not explicitly mentioned in the inquiry's Terms of Reference, it was apparent to the Committee that no inquiry into relations with Africa could ignore the question of official development assistance to that continent. The provision of official development assistance (ODA) is one of the most practical ways Australia can demonstrate its commitment to the Southern African region and its people, and make a positive contribution to regional security. It must be recognised, however, that Australia is a very minor player in development assistance terms, and therefore the aid must be well-targeted if it is to have the maximum impact. 8.2 The need for international assistance to Africa has been universally endorsed in submissions to this inquiry. In examining the social and economic indicators for Africa, it is obvious that great need continues to exist across most of that continent. By the year 2020 it is estimated that Africa will contain 50 per cent of the world's poor.1 8.3 The countries of Southern Africa demonstrate a great range of social and economic conditions. It is unwise to generalise about the level of need in this sub-region; however, it is apparent there are enormous disparities across and within the countries of SADC. Of the 47 countries designated by the United Nations as 'Least Developed Countries' (LDC), six are members of SADC - Angola, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia.2 Mozambique has one of the lowest GNP per capita figures in the world (US$90). -

Nimroz Rapid Drought Assessment Zaranj, Kang and Chakhansoor Districts Conducted August 21St-22Nd 2013

Nimroz Rapid Drought Assessment Zaranj, Kang and Chakhansoor Districts Conducted August 21st-22nd 2013 Figure 1 Dead livestock in Kang district Figure 2 Nimroz district map Relief International in Nimroz Relief International (RI) is a humanitarian, non‐profit, non‐sectarian agency that provides emergency relief, rehabilitation, and development interventions throughout the world. Since 2001, RI has supported a wide array of relief and development interventions throughout Afghanistan. RI programs focus on community participation, ensuring sustainability and helping communities establish a sense of ownership over all stages of the project cycle. Relief International has been working in Nimroz province since 2007, when RI took over implementation of the National Solidarity Program, as well as staff and offices, from Ockenden International. Through more than five years of work in partnership with Nimroz communities, RI has formed deep connections with communities, government, and other stakeholders such as UN agencies. RI has offices and is currently working in all districts of Nimroz, except for the newly added Delaram district (formerly belonging to Farah Province). RI has recently completed an ECHO WASH and shelter program and a DFID funded local governance program , and is currently implementing the National Solidarity Program and a food security and livelihoods program in the province. Nimroz General Information related to Drought Nimroz province is the most South Westerly Province of Afghanistan bordering Iran and Pakistan. The provincial capital is Zaranj, located in the west on the Iranian border. The population is estimated at 350,000 although, as for the rest of Afghanistan, no exact demographic data exists.1 There has been a flow of returnees from Iran over the last years, and the provincial capital has also grown due to internal migration. -

Länderinformationen Afghanistan Country

Staatendokumentation Country of Origin Information Afghanistan Country Report Security Situation (EN) from the COI-CMS Country of Origin Information – Content Management System Compiled on: 17.12.2020, version 3 This project was co-financed by the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund Disclaimer This product of the Country of Origin Information Department of the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum was prepared in conformity with the standards adopted by the Advisory Council of the COI Department and the methodology developed by the COI Department. A Country of Origin Information - Content Management System (COI-CMS) entry is a COI product drawn up in conformity with COI standards to satisfy the requirements of immigration and asylum procedures (regional directorates, initial reception centres, Federal Administrative Court) based on research of existing, credible and primarily publicly accessible information. The content of the COI-CMS provides a general view of the situation with respect to relevant facts in countries of origin or in EU Member States, independent of any given individual case. The content of the COI-CMS includes working translations of foreign-language sources. The content of the COI-CMS is intended for use by the target audience in the institutions tasked with asylum and immigration matters. Section 5, para 5, last sentence of the Act on the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (BFA-G) applies to them, i.e. it is as such not part of the country of origin information accessible to the general public. However, it becomes accessible to the party in question by being used in proceedings (party’s right to be heard, use in the decision letter) and to the general public by being used in the decision. -

Evaluation of Australian Aid to Timor-Leste

Evaluation of Australian aid to Timor-Leste Office of Development Effectiveness June 2014 © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 ISBN 978-0-9874848-1-9 With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms and where otherwise noted all material presented in this document is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/) licence. The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website (accessible using the links provided) as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3.0 AU licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/legalcode). The document must be attributed as Office of Development Effectiveness, Evaluation of Australian aid to Timor-Leste, ODE, Canberra, 2014. Published by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Canberra, 2014. This document is online at www.ode.dfat.gov.au Disclaimer: The views contained in this report do not necessarily represent those of the Australian Government. For further information, contact: Office of Development Effectiveness Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade GPO Box 887 Canberra ACT 2601 Phone (02) 6178 4000 Facsimile (02) 6178 6076 Internet www.ode.dfat.gov.au Cover: Isabella Dacavarhlo maintains her family’s peanut and sweet potato crop while her husband in away in Dili. Isabella is joined by her daughter Elvita Bendita Da Seus Soares who is 7 years old and studies in class 1. Isabella is part of a Seeds of Life support group who received training in effective methods of planting, maintenance and post-harvest. Isabella lives in Salary village, Laga SubDistrict, with her husband and their 6 children. -

Three Ports Under China's Gaze Kulshrestha, Sanatan

www.ssoar.info Three Ports Under China's Gaze Kulshrestha, Sanatan Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kulshrestha, S. (2017). Three Ports Under China's Gaze. IndraStra Global, 8, 1-7. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-53427-9 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. Three Ports Under China’s Gaze indrastra.com/2017/08/Three-Ports-Under-China-s-Gaze-003-08-2017-0050.html By Rear Admiral Dr. -

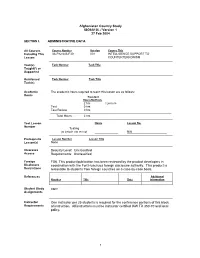

Appendix H- Afghanistan Overview Program of Instruction

Afghanistan Country Study ISO6A10L / Version 1 27 Feb 2004 SECTION I. ADMINISTRATIVE DATA All Courses Course Number Version Course Title Including This 3A-F82/243-F30 001 INTELLIGENCE SUPPORT TO Lesson COUNTERTERRORISM Task(s) Task Number Task Title Taught(*) or Supported Reinforced Task Number Task Title Task(s) Academic The academic hours required to teach this lesson are as follows: Hours Resident Hours/Methods 2 hrs / Lecture Test 0 hrs Test Review 0 hrs Total Hours: 2 hrs Test Lesson Hours Lesson No. Number Testing (to include test review) N/A Prerequisite Lesson Number Lesson Title Lesson(s) None Clearance Security Level: Unclassified Access Requirements: Unclassified Foreign FD6. This product/publication has been reviewed by the product developers in Disclosure coordination with the Fort Huachuca foreign disclosure authority. This product is Restrictions releasable to students from foreign countries on a case-by-case basis. References Additional Number Title Date Information Student Study none Assignments Instructor One instructor per 25 students is required for the conference portions of this block Requirements of instruction. All instructors must be instructor certified IAW TR 350-70 and local policy. 1 Additional Stu Support Name Ratio Qty Man Hours Personnel None Requirements Equipment Id Stu Instr Required Name Ratio Ratio Spt Qty Exp for Instruction 6730-01-T08-4239 25:1 1:25 No 1 No Projector LitePro * Before Id indicates a TADSS Materials Instructor Materials: Required Course Introduction, Lesson Plan, and Slideshow. Student Materials: Notebook and pen. Classroom, CLASSROOM, GEN INSTRUCTION, 1000 SQ FT, 30 PN Training Area, and Range Requirements Ammunition Stu Instr Spt Requirements Id Name Exp Ratio Ratio Qty None Instructional NOTE: Before presenting this lesson, instructors must thoroughly prepare by studying this Guidance lesson and identified reference material. -

ACIAR in Pakistan: 30 Years of Partnership in Research for Development

ACIAR in Pakistan: 30 Years of Partnership in Research for Development ACIAR TECHNICAL REPORTS 91 ACIAR in Pakistan: 30 Years of Partnership in Research for Development Munawar Raza Kazmi, PhD Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research 2017 The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament. ACIAR operates as part of Australia’s international development cooperation program, with a mission to achieve more productive and sustainable agricultural systems, for the benefit of developing countries and Australia. It commissions collaborative research between Australian and developing-country researchers in areas where Australia has special research competence. It also administers Australia’s contribution to the International Agricultural Research Centres. Where trade names are used this constitutes neither endorsement of nor discrimination against any product by ACIAR. ACIAR TECHNICAL REPORTS SERIES This series of publications contains technical information resulting from ACIAR-supported programs, projects and workshops (for which proceedings are not published), reports on Centre-supported fact-finding studies, or reports on other topics resulting from ACIAR activities. Publications in the series are distributed internationally to selected individuals and scientific institutions, and are also available from ACIAR’s website at <aciar.gov.au>. © Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) 2017 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from ACIAR, GPO Box 1571, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia, [email protected] Munawar R.K. 2017. ACIAR in Pakistan: 30 Years of Partnership in Research for Development.