Anna Maria Ortese's Il Mare Non Bagna Napoli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rough Guide to Naples & the Amalfi Coast

HEK=> =K?:;I J>;HEK=>=K?:;je CVeaZh i]Z6bVaÒ8dVhi D7FB;IJ>;7C7B<?9E7IJ 7ZcZkZcid BdcYgV\dcZ 8{ejV HVc<^dg\^d 8VhZgiV HVciÉ6\ViV YZaHVcc^d YZ^<di^ HVciVBVg^V 8{ejVKiZgZ 8VhiZaKdaijgcd 8VhVaY^ Eg^cX^eZ 6g^Zcod / AV\dY^EVig^V BVg^\a^Vcd 6kZaa^cd 9WfeZ_Y^_de CdaV 8jbV CVeaZh AV\dY^;jhVgd Edoojda^ BiKZhjk^jh BZgXVidHVcHZkZg^cd EgX^YV :gXdaVcd Fecf[__ >hX]^V EdbeZ^ >hX]^V IdggZ6ccjco^ViV 8VhiZaaVbbVgZY^HiVW^V 7Vnd[CVeaZh GVkZaad HdggZcid Edh^iVcd HVaZgcd 6bVa[^ 8{eg^ <ja[d[HVaZgcd 6cVX{eg^ 8{eg^ CVeaZh I]Z8Vbe^;aZ\gZ^ Hdji]d[CVeaZh I]Z6bVa[^8dVhi I]Z^haVcYh LN Cdgi]d[CVeaZh FW[ijkc About this book Rough Guides are designed to be good to read and easy to use. The book is divided into the following sections, and you should be able to find whatever you need in one of them. The introductory colour section is designed to give you a feel for Naples and the Amalfi Coast, suggesting when to go and what not to miss, and includes a full list of contents. Then comes basics, for pre-departure information and other practicalities. The guide chapters cover the region in depth, each starting with a highlights panel, introduction and a map to help you plan your route. Contexts fills you in on history, books and film while individual colour sections introduce Neapolitan cuisine and performance. Language gives you an extensive menu reader and enough Italian to get by. 9 781843 537144 ISBN 978-1-84353-714-4 The book concludes with all the small print, including details of how to send in updates and corrections, and a comprehensive index. -

Italian Literature and Civilization: from the Twentieth Century to Today

Université catholique de Louvain - Italian literature and civilization: from the twentieth century to today - en-cours-2019-lrom1373 lrom1373 Italian literature and civilization: from 2019 the twentieth century to today In view of the health context linked to the spread of the coronavirus, the methods of organisation and evaluation of the learning units could be adapted in different situations; these possible new methods have been - or will be - communicated by the teachers to the students. 5 credits 22.5 h + 15.0 h Q2 Teacher(s) Maeder Costantino ; Language : Italian Place of the course Louvain-la-Neuve Prerequisites LFIAL1175, LROM1170 The prerequisite(s) for this Teaching Unit (Unité d’enseignement – UE) for the programmes/courses that offer this Teaching Unit are specified at the end of this sheet. Main themes The course offers students an interdisciplinary presentation of Italian literature, history and history of art from the 20th century to the present day. From the linguistic point of view, students will be introduced to academic writing in Italian. Aims - should know the broad outlines of the cultural history of Italy from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; - have developed the ability to follow a course in Italian; - should be able to understand Italian literary, philosophical, journalistic, cinematic texts; 1 - should be able to provide information on major events of the nineteenth and twentieth century, by analyzing in parallel how they represent the different sources (written and audiovisual); - have developed a high language proficiency in Italian and autonomy in research. - - - - The contribution of this Teaching Unit to the development and command of the skills and learning outcomes of the programme(s) can be accessed at the end of this sheet, in the section entitled “Programmes/courses offering this Teaching Unit”. -

Creatureliness

Thinking Italian Animals Human and Posthuman in Modern Italian Literature and Film Edited by Deborah Amberson and Elena Past Contents Acknowledgments xi Foreword: Mimesis: The Heterospecific as Ontopoietic Epiphany xiii Roberto Marchesini Introduction: Thinking Italian Animals 1 Deborah Amberson and Elena Past Part 1 Ontologies and Thresholds 1 Confronting the Specter of Animality: Tozzi and the Uncanny Animal of Modernism 21 Deborah Amberson 2 Cesare Pavese, Posthumanism, and the Maternal Symbolic 39 Elizabeth Leake 3 Montale’s Animals: Rhetorical Props or Metaphysical Kin? 57 Gregory Pell 4 The Word Made Animal Flesh: Tommaso Landolfi’s Bestiary 75 Simone Castaldi 5 Animal Metaphors, Biopolitics, and the Animal Question: Mario Luzi, Giorgio Agamben, and the Human– Animal Divide 93 Matteo Gilebbi Part 2 Biopolitics and Historical Crisis 6 Creatureliness and Posthumanism in Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò 111 Alexandra Hills 7 Elsa Morante at the Biopolitical Turn: Becoming- Woman, Becoming- Animal, Becoming- Imperceptible 129 Giuseppina Mecchia x CONTENTS 8 Foreshadowing the Posthuman: Hybridization, Apocalypse, and Renewal in Paolo Volponi 145 Daniele Fioretti 9 The Postapocalyptic Cookbook: Animality, Posthumanism, and Meat in Laura Pugno and Wu Ming 159 Valentina Fulginiti Part 3 Ecologies and Hybridizations 10 The Monstrous Meal: Flesh Consumption and Resistance in the European Gothic 179 David Del Principe 11 Contemporaneità and Ecological Thinking in Carlo Levi’s Writing 197 Giovanna Faleschini -

Librib 501200.Pdf

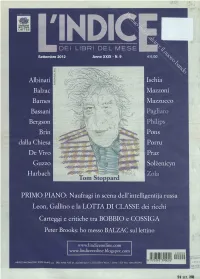

FONDAZIONE BOTTARI LATTES Settembre 2012 Anno XXIX - N. 9 Albinati Ischia Balzac Mazzoni Barnes Mazzucco Bassani Bergson Brin Pons dalla Chiesa Porru De Vivo Praz Guzzo Solzenicyn Harbach PRIMO PIANO: Naufragi in scena del?intelligenti)a russa Leon, Gallino e la LOTTA DI CLASSE dei ricchi Carteggi e critiche tra BOBBIO e COSSIGA Peter Brooks: ho messo BALZAC sul lettino www.lindiceonline.com www.lindiceonline.blogspot.com MENSILE D'INFORMAZIONE - POSTE ITALIANE s.p.a. - SPED. IN ABB. POST. D.L. 353/2003 (conv.in L. 27/02/2004 n° 46) art. I, comma ], DCB Torino - ISSN 0393-3903 Editoria La verità è destabilizzante Per Achille Erba di Lorenzo Fazio Quando è mancato Achille Erba, uno dei fon- ferimento costante al Vaticano II e all'episcopa- a domanda è: "Ma ci quere- spezzarne il meccanismo di pro- datori de "L'Indice", alcune persone a lui vicine to di Michele Pellegrino) sono ampiamente illu- Lleranno?". Domanda sba- duzione e trovare (provare) al- hanno deciso di chiedere ospitalità a quello che lui strate nel sito www.lindiceonline.com. gliata per un editore che si pre- tre verità. Come editore di libri, ha continuato a considerare Usuo giornale - anche È opportuna una premessa. Riteniamo si sarà figge il solo scopo di raccontare opera su tempi lunghi e incrocia quando ha abbandonato l'insegnamento universi- tutti d'accordo che le analisi e le discussioni vol- la verità. Sembra semplice, ep- passato e presente avendo una tario per i barrios di Santiago del Cile e, successi- te ad illustrare e approfondire nei suoi diversi pure tutta la complessità del la- prospettiva anche storica e più vamente, per una vita concentrata sulla ricerca - aspetti la ricerca storica di Achille e ad indivi- voro di un editore di saggistica libera rispetto a quella dei me- allo scopo di convocare un'incontro che ha lo sco- duare gli orientamenti generali che ad essa si col- di attualità sta dentro questa pa- dia, che sono quotidianamente po di ricordarlo, ma anche di avviare una riflessio- legano e che eventualmente la ispirano non pos- rola. -

Valerie Mcguire, Phd Candidate Italian Studies Department, New York University La Pietra, Florence; Spring, 2012

Valerie McGuire, PhD Candidate Italian Studies Department, New York University La Pietra, Florence; Spring, 2012 The Mediterranean in Theory and Practice The Mediterranean as a category has increasingly gained rhetorical currency in social and cultural discourses. It is used to indicate not only a geographic area but also a set of traditional and even sacrosanct human values, while encapsulating fantasies of both environmental utopia and dystopia. While the Mediterranean diet and “way of life” is upheld as an exemplary counterpoint to our modern condition, the region’s woes cast a shadow over Europe and its enlightened, rationalist ideals—and most recently, has even undermined the project of the European Union itself. The Mediterranean is as often positioned as the floodgate through which trickles organized crime, political corruption, illegal immigration, financial crisis, and more generally, the malaise of globalization, as it is imagined as a utopian This course explores different symbolic configurations of the Mediterranean in twentieth- and twenty-first-century Italian culture. Students will first examine different theoretical approaches (geophysical, historical, anthropological), and then turn to specific textual representations of the Mediterranean, literary and cinematic, and in some instances architectural. We will investigate how representations of the Mediterranean have been critical to the shaping of Italian identity as well as the role of the Mediterranean to separate Europe and its Others. Readings include Fernand Braudel, Iain Chambers, Ernesto de Martino, Elsa Morante, Andrea Camillieri, and Amara Lakhous. Final projects require students to isolate a topic within Italian culture and to develop in situ research that examines how the concept of the Mediterranean may be used to codify, or in some instances justify, certain textual or social practices. -

Melodrama Or Metafiction? Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels

This is a repository copy of Melodrama or metafiction? Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/126344/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Santovetti, O (2018) Melodrama or metafiction? Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels. Modern Language Review, 113 (3). pp. 527-545. ISSN 0026-7937 https://doi.org/10.5699/modelangrevi.113.3.0527 (c) 2018 Modern Humanities Research Association. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Modern Language Review. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Melodrama or metafiction? Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels Abstract The fusion of high and low art which characterises Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels is one of the reasons for her global success. This article goes beyond this formulation to explore the sources of Ferrante's narrative: the 'low' sources are considered in the light of Peter Brooks' definition of the melodramatic mode; the 'high' component is identified in the self-reflexive, metafictional strategies of the antinovel tradition. -

Scarica Rassegna Stampa

Sommario N. Data Pag Testata Articolo Argomento 1 07/08/2020 68,... SETTE MAURIZIO DE GIOVANNI ° EINAUDI 2 18/08/2020 WEB ANSA.IT >>>ANSA/LIBRI, GRANDE AUTUNNO ITALIANO DA TAMARO A MAGRIS ° EINAUDI L'INTERVISTA: MAURIZIO DE GIOVANNI. NAPOLI ORA DEVE RISORGERE IN COMUNE ARIA 3 19/08/2020 6 LA REPUBBLICA NAPOLI NUOVA" ° EINAUDI 4 19/08/2020 33 LA PROVINCIA PAVESE DALLA TAMARO A DE CARLO UN GRANDE AUTUNNO TRA RITORNI E SORPRESE ° EINAUDI 5 20/08/2020 44 L'ARENA DA CAROFIGLIO A PENNACCHI, AUTUNNO DI LIBRI ° EINAUDI 6 20/08/2020 34 LA SICILIA E CON L'AUTUNNO CADONO... I LIBRI ° EINAUDI 7 12/09/2020 42,... CORRIERE DELLA SERA IMPOSSIBILE RESISTERE SE TI AFFERRA SETTEMBRE ° EINAUDI 8 12/09/2020 37 LA GAZZETTA DEL MEZZOGIORNO 19ª EDIZIONE "I DIALOGHI DI TRANI ° EINAUDI 9 14/09/2020 WEB AMICA.IT 16 IMPERDIBILI NUOVI LIBRI DA LEGGERE IN USCITA NELL'AUTUNNO 2020 ° EINAUDI 10 15/09/2020 WEB CORRIEREDELMEZZOGIORNO.CORRIERE.IT MAURIZIO DE GIOVANNI E IL CICLONE MINA SETTEMBRE ° EINAUDI 11 15/09/2020 1,1... CORRIERE DEL MEZZOGIORNO (NA) DE GIOVANNI EMINA SETTEMBRE COSÌ LA CITTÀ TORNA A COLORARSI ° EINAUDI Data: 07.08.2020 Pag.: 68,69,70,71,72 Size: 2541 cm2 AVE: € .00 Tiratura: Diffusione: Lettori: Codice cliente: null OPERE Maurizio de Giovanni (Napoli, 1958) è diventato famoso con i del sangue, Il giorno dei morti, Vipera (Premio Viareggio, Premio Camaiore), In fondo al tuo cuore, Anime MAURIZIO di vetro, Il purgatorio dell'angelo e Il pianto dell'alba Stile Libero). Dopo Il metodo del Coccodrillo (Mondadori 2012; Einaudi Stile Libero 2016; Premio Scerbanenco), con I Bastardi di Pizzofalcone (2013) ha dato inizio Maurizio de a un nuovo Giovanni è nato Stile Libero e partecipando diventato una a un concorso serie Tv per Rai 1) ° EINAUDI 1 Data: 07.08.2020 Pag.: 68,69,70,71,72 Size: 2541 cm2 AVE: € .00 Tiratura: Diffusione: Lettori: SPECIALE LIBRI LA CONVERSAZIONE di ROBERTA SCORRANESE foto di SERGIO SIANO "NAPOLIASSOMIGLIA AUNACIPOLLA QUILESTORIENON FINISCONOEIMORTI STANNOCONIVIVI" DEGIOVANNI MauriziodeGiovannièinlibertàvigilata. -

The RUTGERS LIBRETTO Newsletter of the Italian Department IV N

RUTGERS DEPARTMENT OF ITALIAN SPRING 2015 The RUTGERS LIBRETTO Newsletter of the Italian Department IV n. 1 Letter from the Chair TABLE OF CONTENTS am delighted to report that the Italian front cover I FROM THE CHAIR Department at Rutgers is in excellent shape, Paola Gambarota in spite of the recent ups and downs of the 2 HIGHLIGHTS Humanities in the US. We just celebrated the Sheri La Macchia & graduation of 21 seniors, out of 46 majors, during Carmela Scala a joyful evening attended by 74 people. Three 4 UNDERGRADUATE NEWS ABOVE: Paola Gambarota among our seniors completed an honors thesis. & ITALIAN NIGHT We were very impressed when students attending Prof. Rhiannon Welch’s senior 6 LECTURES & IGS seminar organized a two-day conference on the topic of “New and Old Italian 8 RUTGERS DAY Identities,” demonstrating a strong commitment to explore timely issues of 10 GRADUATE NEWS citizenship and immigration. One of these students, Nicoletta Romano, continued to study these questions with the support of the Lloyd Gardner Fellowship Program 12 ALUMNI REUNION & NEWS in Leadership and Social Policy, under the guidance of Professor Welch. Another 16 FACULTY NEWS Italian major, Mihaela Sanderson, was selected as the author of the “Best Poster” for back cover the Humanities portion of the Aresty Symposium, the result of a research project DEPARTMENT INITIATIVES developed with the support of her mentor Prof. Andrea Baldi. This is the second consecutive time that a student majoring in Italian is recognized in this way. There have been some changes in our department, and we miss our former friends and colleagues, our beloved Carol Feinberg, our kindhearted Robin Rogers, and our former language coordinator Daniele de Feo. -

PDF-Dokument

1 COPYRIGHT Dieses Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Es darf ohne Genehmigung nicht verwertet werden. Insbesondere darf es nicht ganz oder teilweise oder in Auszügen abgeschrieben oder in sonstiger Weise vervielfältigt werden. Für Rundfunkzwecke darf das Manuskript nur mit Genehmigung von Deutschlandradio Kultur benutzt werden. KULTUR UND GESELLSCHAFT Organisationseinheit : 46 Reihe : LITERATUR Kostenträger : P 62 300 Titel der Sendung : Das bittere Leben. Zum 100. Geburtstag der italienischen Schriftstellerin Elsa Morante AutorIn : Maike Albath Redakteurin : Barbara Wahlster Sendetermin : 12.8.2012 Regie : NN Besetzung : Autorin (spricht selbst), Sprecherin (für Patrizia Cavalli und an einer Stelle für Natalia Ginzburg), eine Zitatorin (Zitate und Ginevra Bompiani) und einen Sprecher. Autorin bringt O-Töne und Musiken mit Dieses Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt und darf vom Empfänger ausschließlich zu rein privaten Zwecken genutzt werden. Jede Vervielfältigung, Verbreitung oder sonstige Nutzung, die über den in den §§ 45 bis 63 Urheberrechtsgesetz geregelten Umfang hinausgeht, ist unzulässig © Deutschlandradio Deutschlandradio Kultur Funkhaus Berlin Hans-Rosenthal-Platz 10825 Berlin Telefon (030) 8503-0 2 Das bittere Leben. Zum hundertsten Geburtstag der italienischen Schriftstellerin Elsa Morante Von Maike Albath Deutschlandradio Kultur/Literatur: 12.8.2012 Redaktion: Barbara Wahlster Regie: Musik, Nino Rota, Fellini Rota, „I Vitelloni“, Track 2, ab 1‘24 Regie: O-Ton Collage (auf Musik) O-1, O-Ton Patrizia Cavalli (voice over)/ Sprecherin Sie war schön, wunderschön und sehr elegant. Unglaublich elegant und eitel. Sie besaß eine großartige Garderobe. O-2, O-Ton Ginevra Bompiani (voice over)/ Zitatorin Sie war eine ungewöhnliche Person. Anders als alle anderen. O- 3, Raffaele La Capria (voice over)/ Sprecher An Elsa Morante habe ich herrliche Erinnerungen. -

Delirious NAPLES

HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY presents A Conference DELIRIOUS NAPLES: FOR A CULTURAL, INTELLECTUAL, and URBAN HISTORY of the CITY of the SUN HOFSTRA CULTURAL CENTER, HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, November 16, 17, 18, 2011 and CASA ITALIANA ZERILLI-MARIMÒ, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Saturday, November 19, 2011 In memoriam Thomas V. Belmonte (1946-1995), author of The Broken Fountain We gratefully acknowledge the participation and generous support of: Hofstra University Office of the President Hofstra University Office of the Provost Hofstra College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Office of the Dean Lackmann Culinary Services Il Villaggio Trattoria, Malverne, NY, Antonio Bove, master chef Il Gattopardo, New York, NY, Gianfranco Sorrentino, owner, restaurateur Iavarone Bros., Wantagh, NY Supreme Wine Distributors, Pleasantville, NY Salvatore Mendolia Queensboro UNICO Coccia Foundation New Yorker Films CIAO, Hofstra University Hofstra University Department of Comparative Literature and Languages Hofstra University Department of History Hofstra University Department of Music Hofstra University Department of Romance Languages and Literatures Hofstra University European Studies Program Hofstra University Honors College Hofstra University Museum Hofstra University Women’s Studies Program Regione Campania Ente Provinciale per il Turismo di Caserta Lorenzo Zurino, Piano di Sorrento Tina Piscop, East Meadow, NY The participation of conference scholars may be subject to their professional or academic commitments. Cover Image Credit: Carosello Napoletano, 1954 Ettore Giannini, Director Movie Still HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY presents A Conference DELIRIOUS NAPLES: FOR A CULTURAL, INTELLECTUAL, and URBAN HISTORY of the CITY of the SUN HOFSTRA CULTURAL CENTER CASA ITALIANA ZERILLI-MARIMÒ HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Wednesday, Thursday, Friday Saturday, November 19, 2011 November 16, 17, 18, 2011 Stuart Rabinowitz Janis M. -

Il Castellet 'Italiano' La Porta Per La Nuova Letteratura Latinoamericana

Rassegna iberistica ISSN 2037-6588 Vol. 38 – Num. 104 – Dicembre 2015 Il Castellet ‘italiano’ La porta per la nuova letteratura latinoamericana Francesco Luti (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, España) Abstract This paper seeks to recall the ‘Italian route’ of the critic Josep Maria Castellet in the last century, a key figure in Spanish and Catalan literature. The Italian publishing and literary worlds served as a point of reference for Castellet, and also for his closest literary companions (José Agustín Goytisolo and Carlos Barral). All of these individuals formed part of the so-called Barcelona School. Over the course of at least two decades, these men managed to build and maintain a bridge to the main Italian publishing houses, thereby opening up new opportunities for Spanish literature during the Franco era. Thanks to these links, new Spanish names gained visibility even in the catalogues of Italian publishing houses. Looking at the period from the mid- 1950s to the end of the 1960s, the article focuses on the Italian contacts of Castellet as well as his publications in Italy. The study concludes with a comment on his Latin American connections, showing how this literary ‘bridge’ between Barcelona and Italy also contributed to exposing an Italian audience to the Latin American literary boom. Sommario 1. I primi contatti. – 2. Dario Puccini e i nuovi amici scrittori. – 3. La storia italiana dei libri di Castellet. – 4. La nuova letteratura proveniente dall’America latina. Keywords Literary relationships Italy-Spain. 1950’s 1960’s. Literary criticism. Spanish poetry. Alla memoria del Professor Gaetano Chiappini e del ‘Mestre’ Castellet. -

History and Emotions Is Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena

NARRATING INTENSITY: HISTORY AND EMOTIONS IN ELSA MORANTE, GOLIARDA SAPIENZA AND ELENA FERRANTE by STEFANIA PORCELLI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 STEFANIA PORCELLI All Rights Reserved ii Narrating Intensity: History and Emotions in Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena Ferrante by Stefania Porcell i This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________ ______________________________ Date [Giancarlo Lombardi] Chair of Examining Committee ________ ______________________________ Date [Giancarlo Lombardi] Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Monica Calabritto Hermann Haller Nancy Miller THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Narrating Intensity: History and Emotions in Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena Ferrante By Stefania Porcelli Advisor: Giancarlo Lombardi L’amica geniale (My Brilliant Friend) by Elena Ferrante (published in Italy in four volumes between 2011 and 2014 and translated into English between 2012 and 2015) has galvanized critics and readers worldwide to the extent that it is has been adapted for television by RAI and HBO. It has been deemed “ferocious,” “a death-defying linguistic tightrope act,” and a combination of “dark and spiky emotions” in reviews appearing in popular newspapers. Taking the considerable critical investment in the affective dimension of Ferrante’s work as a point of departure, my dissertation examines the representation of emotions in My Brilliant Friend and in two Italian novels written between the 1960s and the 1970s – La Storia (1974, History: A Novel) by Elsa Morante (1912-1985) and L’arte della gioia (The Art of Joy, 1998/2008) by Goliarda Sapienza (1924-1996).