That Was the Worst Christmas Ever!”)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Exhibition 200 Years Silent Night! Holy Night! English

State Exhibition 200 years Silent Night! www.stillenacht.com Holy Night! English Salzburg Oberndorf Arnsdorf Austria’s Hallein message of peace Hintersee to the world Wagrain September 29, 2018 – Mariapfarr February 3, 2019 Hochburg-Ach Fügen im Zillertal www.landesausstellung2018.at City of Salzburg Salzburg Museum Silent Night 200 – History. Message. Presence. Joseph Mohr was born to an unwed mother on December 11, 1792, in Salzburg and baptized in the Salzburg Cathedral. Recognizing the young man’s talent, the vicar of the cathedral choir took Mohr under his wing, helping him with his educa- tion and fi nally his career as a priest. In 1816, he penned the lyrics to the song while on his fi rst assignment in Mariapfarr. Mohr met Franz Xaver Gruber, a teacher from Arnsdorf and the compos- er of the melody, when he moved to Oberndorf in 1817. Together they performed the song for the very fi rst time. This special exhibition touches on the history, message, and the continuing pres- ence of this world-renowned song. The exhibition is divided into six themes: the history of the song, the life stories of its creators, Mohr and Gruber, the tradition and distribution of the song, and the political and commercial instrumentalization. Salzburg Museum Neue Residenz Mozartplatz 1, 5010 Salzburg Information and guided tours: +43 662 620808-200 offi [email protected] www.salzburgmuseum.at Opening hours: Tue. – Sun. 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m (Christmas opening hours on the website in December) © SLTG/Salzburg Museum © SLTG/Salzburg Manufacturer: Druckerei Roser GmbH, Hallwang. Misprints and printing errors reserved. -

“White Christmas”—Bing Crosby (1942) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Cary O’Dell

“White Christmas”—Bing Crosby (1942) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Cary O’Dell Crosby’s 1945 holiday album Original release label “Holiday Inn” movie poster With the possible exception of “Silent Night,” no other song is more identified with the holiday season than “White Christmas.” And no singer is more identified with it than its originator, Bing Crosby. And, perhaps, rightfully so. Surely no other Christmas tune has ever had the commercial or cultural impact as this song or sold as many copies--50 million by most estimates, making it the best-selling record in history. Irving Berlin wrote “White Christmas” in 1940. Legends differ as to where and how though. Some say he wrote it poolside at the Biltmore Hotel in Phoenix, Arizona, a reasonable theory considering the song’s wishing for wintery weather. Some though say that’s just a good story. Furthermore, some histories say Berlin knew from the beginning that the song was going to be a massive hit but another account says when he brought it to producer-director Mark Sandrich, Berlin unassumingly described it as only “an amusing little number.” Likewise, Bing Crosby himself is said to have found the song only merely adequate at first. Regardless, everyone agrees that it was in 1942, when Sandrich was readying a Christmas- themed motion picture “Holiday Inn,” that the song made its debut. The film starred Fred Astaire and Bing Crosby and it needed a holiday song to be sung by Crosby and his leading lady, Marjorie Reynolds (whose vocals were dubbed). Enter “White Christmas.” Though the film would not be seen for many months, millions of Americans got to hear it on Christmas night, 1941, when Crosby sang it alone on his top-rated radio show “The Kraft Music Hall.” On May 29, 1942, he recorded it during the sessions for the “Holiday Inn” album issued that year. -

The English Listing

THE CROSBY 78's ZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBAthe English listing Members may recall that we issued a THE questionnaire in 1990 seeking views and comments on what we should be providing in CROSBY BING. We are progressively attempting to fulfil 7 8 's these wishes and we now address one major ENGLISH request - a listing of the 78s issued in the UK. LISTING The first time this listing was issued in this form was in the ICC's 1974 booklet and this was updated in 1982in a publication issued by John Bassett's Crosby Collectors Society. The joint compilers were Jim Hayes, Colin Pugh and Bert Bishop. John has kindly given us permission to reproduce part of his publication in BING. This is a complete listing of very English-issued lO-inch and 12-inch 78 rpm shellac record featuring Sing Crosby. In all there are 601 discs on 10different labels. The sheet music used to illustrate some of the titles and the photos of the record labels have been p ro v id e d b y Don and Peter Haizeldon to whom we extend grateful thanks. NUMBERSITITLES LISTING OF ENGLISH 78"s ARIEl GRAND RECORD. THE 110-Inchl 4364 Susiannainon-Bing BRUNSWICK 112-inchl 1 0 5 Gems from "George White's Scandals", Parts 1 & 2 0 1 0 5 ditto 1 0 7 Lawd, you made the night too long/non-Bing 0 1 0 7 ditto 1 1 6 S I. L o u is blues/non-Bing _ 0 1 3 4 Pennies from heaven medley/Pennies from heaven THECROSBYCOLLECTORSSOCIETY BRUNSWICK 110-inchl 1 1 5 5 Just one more chance/Were you sincere? 0 1 6 0 8 Home on the range/The last round-up 0 1 1 5 5 ditto 0 1 6 1 5 Shadow waltz/I've got to sing a torch -

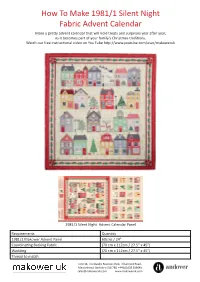

How to Make 1981/1 Silent Night Fabric Advent Calendar

How To Make 1981/1 Silent Night Fabric Advent Calendar Make a pretty advent calendar that will hold treats and surprises year after year, as it becomes part of your family’s Christmas traditions. Watch our free instructional video on You Tube http://www.youtube.com/user/makoweruk 1981/1 Silent Night Advent Calendar Panel Requirements Quantity 1981/1 Makower Advent Panel 60cms / 24” Coordinating Backing Fabric (70 cm x 112cm / 27.5” x 45”) Wadding (70 cm x 112cm / 27.5” x 45”) Thread to match Unit 14, Cordwallis Business Park, Clivemont Road, Maidenhead, Berkshire SL6 7BU +44(0)1628 509640 [email protected] www.makoweruk.com Sewing Instructions For Advent Calendar Make these easy to construct advent calendars and fill them with your own choice of sweets and treats for Christmas. Wendy Gardiner provides some simple steps and tips to make up the panels easily and quickly. 1. Cut out the panel around the border. Next cut out the pockets, cutting along the solid lines only. 2. On each pocket strip fold under the top edge to the wrong side and press in place. 3. Using the edge of the presser foot as a guide for the edge of the fabric, move the needle across to the right with the stitch width button and top stitch the turned edge of pocket strips in place. 4. Press the stitched tops. 5. To make the box pleats, pinch a fold in the pocket edge and fold it towards the blue dotted line and press in place. Repeat for the other side, and pin in place so that the folds at the bottom of the pockets are butted against each other. -

Night of Silence Is a Christmas Carol and Advent Hymn, Written in 1981 by American Composer, Daniel Kantor, and Then Published in 1984

Night of Silence is a Christmas carol and Advent hymn, written in 1981 by American composer, Daniel Kantor, and then published in 1984. The carol is a quodlibet the term used for a partner song that can be sung simultaneously with another song. Night of Silence can be sung simultaneously with the Christmas carol Silent Night. See music with and without piano accompaniment below Silent Night - Night of Silence - Stille Nacht https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qmgnx5OgvsI Listen to YouTube Night of Silence / Silent Night - Gonzaga University Choirs presentations https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bcXfM-wc30c Swiss Choir "Silent Night/Night of Silence https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HPRb_yo9dow Night of Silence by Daniel Kantor Cold are the people, Winter of life, We tremble in shadows this cold endless night, Frozen in the snow lie roses sleeping, Flowers that will echo the sunrise, Fire of hope is our only warmth, Weary, its flame will be dying soon. Voice in the distance, call in the night, On wind you enfold us you speak of the light, Gentle on the ear you whisper softly, Rumors of a dawn so embracing, Breathless love awaits darkened souls, Soon will we know of the morning. Spirit among us, Shine like the star, Your light that guides shepherds and kings from afar, Shimmer in the sky so empty, lonely, Rising in the warmth of your Son's love, Star unknowing of night and day, Spirit we wait for your loving Son. SSSSttttiiiilllllllleeee NNNNaaaacccchhhhtttt SSSSiiiilllleeeennnntttt NNNNiiiigggghhhhtttt Composer Franz Xaver Gruber (1787-1863) John Freeman Young (verses 1-3), ca. -

Concert Band Performance Music

424 CONCERT BAND PERFORMANCE MUSIC NAfrican Spirit Dance Amazing Grace ALPHABETICAL LISTING (O’Reilly) (1.5) (AOA) ...................$42.00 00-26794____ (Traditional American Melody/Arr. Ployhar) (2.5) (BCB) BY TITLE An African-American Air .........................................................$60.00 00-BDM05011____ (Traditional/Arr. Mixon) (1) (BBB) Amazing Grace Numeric .........................................................$45.00 00-26704____ (Traditional/Arr. Bullock) (1) (BBB) An Afternoon at the Ballet .........................................................$45.00 00-BD01035____ 71, 2, 3, 4 (Arr. O’Reilly) (1) (YB) ..................$40.00 00-5160____ 7Amazing Grace with the Last Post As performed by Plain White T’s Air and Allegro (Traditional/Arr. Wade-West) (2) (HPB) ........................................$50.00 00-34072____ .........................................................$35.00 81-CB2250____ (Feldstein & O’Reilly) (1) (YB) 4 Minutes .........................................................$40.00 00-3453____ 8 America - Land of Liberty (Madonna et al) (2) (HPB) Air and Alleluia (Arr. Hodges) (1.5) (CH) ................ $TBD 00-33826____ .........................................................$50.00 00-29859____ (Mozart/Kinyon) (1) (MS) ...........$40.00 00-904____ NAmerica the Beautiful The 20th Century Band Air and Dance (Arr. Dragon) (3.5)........................$60.00 00-FXB123____ (Coakley)........................................$58.00 81-CB975____ (Kinyon) (1) (MS) .........................$40.00 00-2137____ -

Hndel's Messiah Silent Night, Holy Night

11t15t2018 The oldest Christmas carols Hndel's Messiah Georg Friederich Hndel was born in Germany in 1685" The Royal Houses of Britain and Europe had always been closely interrelated, and the Act of Settlement of 1701 secured the Protestant succe$sion of Anne to the Crown. Hndel, who had studied and perforrned in Europe, left ltaly early in 1710 for Hanover, where he was appointed Kapellmeister to the Elector, George Louis. ln Augusl 1714, at the death of Queen Anne, George became George l, king of Britain. Hndel foilowed George and adopted British nationality. By invitation of the Duke of Devonshire, who was anxious to further music in Dublin, Hndel moved to lreland. ln 1742, he gave the first performance of the hdessiah in the Music Hall, Fishamble Street, Dublin in aid of several charities. By 1170, the famous Messiah was performed in Colonial America, 2 years before its first performance in his native Germany. Hndel died in 1759 and was buried in Westminster Abbey, recognized in England as the greatest composer of his day. Flis Messiah was a$ popular then as Bing Crosby's White Christmas is today" Silent Night, Holy Night Perhaps the best known Christrnas carol is Silent Night, wriiten in 1818 by an Austrian assistant priest Jaseph hiiohr. He was told the day before Christmas that the chunch CIrgan was broken and wculd not be repaired in time for Christmas Day" Saddened, he sat down to write three stanzas that could be sung by choir to guitar music. "Stille Nacht, Heilige Nacht" was heard for the first time at that Midnight Mass in St. -

90'S-2000'S Ballads 1. with Open Arms

90’s-2000’s Ballads 14. Fooled Around And Fell In Love - Elvin Bishop 1. With Open Arms - Creed 15. I Just Wanna Stop - Gino Vannelli 2. Truly Madly Deeply - Savage Garden 16. We've Only Just Begun - The Carpenters 3. I Knew I Loved You - Savage Garden 17. Easy - Commodores 4. As Long As You Love Me - Backstreet Boys 18. Three Times A Lady - Commodores 5. Last Kiss - Pearl Jam 19. Best Of My Love - Eagles 6. Aerosmith - Don't Wanna Miss A Thing 20. Lyin' Eyes - Eagles 7. God Must Have Spent A Little More Time - N'Sync 21. Oh Girl - The Chi-Lites 8. Everything I Do - Bryan Adams 22. That's The Way Of The World - Earth Wind & Fire 9. Have I Told You Lately - Rod Stewart 23. The Wedding Song - Paul Stokey 10. When A Man Loves A Woman - Michael Bolton 24. Wonder Of You - Elvis Presley 11. Oh Girl - Paul Young 25. You Are The Sunshine Of My Life - Stevie Wonder 12. Love Will Keep Us Alive - Eagles 26. You've Got A Friend - James Taylor 13. Can You Feel The Love Tonight - Elton John 27. Annie's Song - John Denver 14. I Can't Fight This Feeling Anymore - R.E.O. 28. Free Bird - Lynyrd Skynyrd 15. Unforgettable - Natalie Cole 29. Riders On The Storm - Doors 16. Endless Love - Luther Vandross 30. Make It With You - Bread 17. Forever In Love - Kenny G 31. If - Bread 18. Butterfly Kisses - Bob Carlisle 32. Fallin' In Love - Hamilton, Joe Frank & Reynolds 19. Unforgettable - Nat King & Natalie Cole 33. -

Holding Children in Prayer: an Advent Devotional

Holding Children inPrayer AN ADVENT GUIDE About the Children’ s Defense Fund The Children’s Defense Fund’s Leave No Child Behind® mission is to ensure every child a Healthy Start, a Head Start, a Fair Start, a Safe Start, and a Moral Start in life and successful passage to adulthood with the help of caring families and communities. CDF provides a strong, effective voice for all the children of America who cannot vote, lobby, or speak for themselves. We pay particular attention to the needs of poor and minority children and those with disabilities. CDF educates the nation about the needs of children and encourages preventive investments before they get sick or into trouble, drop out of school, or suffer family breakdown. CDF began in 1973 and is a private, nonprofit organization supported by foundation and corporate grants and individual donations. We have never taken government funds. For more than 30 years, CDF has worked in partnership with the religious community to respond to the needs of poor and neglected children through worship, direct service, public education, community outreach, and advocacy. The CDF-coordinated National Observance of Children’s Sabbaths® cele- bration, observed every October, offers all people of faith the opportunity to renew their commitment to children annually. The annual Samuel DeWitt Proctor Institute for Child Advocacy Ministry, held at CDF Haley Farm in Tennessee each July, offers spiritual renewal, networking, and continuing education for religious leaders and other faith-based child advocates. Contact CDF’s Religious Action Division at (202) 662-3579 for more information. Holding Children inPrayer AN ADVENT GUIDE By Shannon Daley-Harris Acknowledgments I am deeply grateful to the following people who generously and thoughtfully provided various forms of assistance with this publication: The Rev. -

20352 La Virgen De La Macarena OK

La Virgen De La Macarena Saxophone Quartet Keyboard & Drums (optional) Arr.: Jérôme Naulais EMR 20352 Dieser Titel enthält alle transponierten Stimmen Ce titre contient toutes les voix transposées This title contains all the transposed parts 1. Stimme / Voix / Part B Soprano Saxophone E Alto Saxophone 2. Stimme / Voix / Part E Alto Saxophone B Tenor Saxophone 3. Stimme / Voix / Part E Alto Saxophone B Tenor Saxophone 4. Stimme / Voix / Part E Baritone Saxophone Partitur / Direction / Score Keyboard (optional) Drums (optional) Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch La Virgen De La Macarena | Photocopying is illegal! Arr.: Jérôme Naulais 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Maestoso q = 116 3 3 B Soprano Saxophone b or E b Alto Saxophone f Eb Alto Saxophone or B b Tenor Saxophone f Eb Alto Saxophone or B b Tenor Saxophone f Eb Baritone Saxophone f C B¨m Keyboard (optional) f f Drums (optional) f 8 9 10 11 12$ 13 14 rit.A poco meno mosso B Sop.Sax. or Alt.Sax. mf f Alt.Sax. or Ten.Sax. mp f Alt.Sax. or Ten.Sax. mp f Bar.Sax. mp f C Db B¨m C f Keyb. mp f Dr. 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 C Sop.Sax. or Alt.Sax. mf Alt.Sax. or Ten.Sax. mp f Alt.Sax. or Ten.Sax. mp f Bar.Sax. mp f C Db B¨m Keyb. -

78 Rpm 12-Inch Records

RECORDS PRODUCED by the Inland Children's Chorus Production dates not identified on record labels are based on mailer postmark dates and evidence from concert programs, label design, and firsthand accounts of former members. Composers and arrangers not identified on record labels are based on concert program listings and contemporary sheet music. 78 rpm 12-inch Records Story of Bethlehem (Three-record set) with narration by Paul Allison 1940 [A1] Side 1: Story of Bethlehem 1940 [A2] Side 6: Story of Bethlehem 1940 [B1] Side 2: Story of Bethlehem 1940 [B2] Side 5: Story of Bethlehem 1940 [C1] Side 3: Story of Bethlehem 1940 [C2] Side 4: Story of Bethlehem Special Album (Three-record set) 1940 [D1] Part 1: Glory to God in the Highest (Pergolesi) 1940 [D2] Part 2a: O Little Town of Bethlehem (Redner) Part 2b: Hark! The Herald Angels Sing (Mendelssohn) 1940 [E1] Part 3: O Holy Night (Adam) 1940 [E2] Part 4: Gesù Bambino (Yon) 1940 [F1] Part 5: Silent Night (Gruber) with narration by Paul Allison 1940 [F2] Part 6a: Ave Maria (Vittoria arr. by Deems Taylor) Part 6b: The First Nowell (trad. harmonized by Stainer) 1945 (Two records) 1945 [A1] Alice Blue Gown (Tierney) 1945 [A2] Song of Love (Romberg) 1945 [B1] The Lord's Prayer (Malotte) 1945 [B2] Irish Lullaby: "Too-ra-loo-ra-loo-ral (That's an Irish Lullaby)" (Shannon) 1946 (Four records) 1946 [A1] Deep in My Heart (Romberg) 1946 [A2] Stardust (Carmichael) 1946 [B1] Tales from the Vienna Woods (Strauss) 1946 [B2] Valse Triste (Sibelius) 1946 [Audiodisc 1] The Rangers' Song (Tierney) 1947 [Audiodisc -

Silent Night Stille Nacht - Douce Nuit

Silent Night Stille Nacht - Douce Nuit Brass Band Adapt.: Bertrand Moren Arr. : Marcel Saurer EMR 3162 st + 1 Full Score 2 1 B Trombone nd + 1 E Cornet 2 2 B Trombone + 3 Solo B Cornet I 1 Bass Trombone 3 Solo B Cornet II 2 Euphonium 1 Repiano Cornet 2 E Bass nd 3 2 B Cornet 2 B Bass rd 3 3 B Cornet 1 Piano / Guitar / Bass Guitar (optional) 1 B Flugelhorn 1 Glockenspiel 2 Solo E Horn 1 Drum Set st 2 1 E Horn nd 2 2 E Horn st 2 1 B Baritone nd 2 2 B Baritone Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter www.reift.ch Case Postale 308 • CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 • Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 • E-Mail : [email protected] • www.reift.ch DISCOGRAPHY Swingle Bells Track Titel / Title Time N° EMR N° EMR N° (Komponist / Composer) Blasorchester Brass Band Concert Band 1 O Christmas Tree (Arr.: Parson) 3’08 EMR 10745 EMR 3154 2 Ox And Donkey Blues (Arr.: Saurer) 2’53 EMR 10753 EMR 3155 3 Joyful Christmas (Arr.: Parson) 3’01 EMR 10748 EMR 3156 4 Adeste Fideles (Arr.: Saurer) 2’59 EMR 10751 EMR 3157 5 King’s Blues March (Arr.: Saurer) 3’14 EMR 10752 EMR 3158 6 Christmas Swing (Arr.: Parson) 3’18 EMR 10754 EMR 3159 7 A Merry Christmas (Arr.: Parson) 3’16 EMR 10743 EMR 3160 8 Kling Glöckchen (Arr.: Parson) 3’36 EMR 10746 EMR 3161 9 Silent Night (Arr.: Saurer) 3’08 EMR 10744 EMR 3162 10 Swingle Bells (Arr.: Parson) 3’12 EMR 10741 EMR 3163 11 What Child Is This ? (Arr.: Parson) 3’09 EMR 10742 EMR 3164 12 Holy Night (Arr.: Parson) 3’16 EMR 10747 EMR 3165 13 Christmas Glory (Arr.: Parson) 3’34 EMR 10750 EMR 3166 14 Go Tell It On The Mountain (Arr.: Parson) 3’12 EMR 10749 EMR 3167 Zu bestellen bei • A commander chez • To be ordered from: Editions Marc Reift • Route du Golf 150 • CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) • Tel.