Silent Night Full Score

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

State Exhibition 200 Years Silent Night! Holy Night! English

State Exhibition 200 years Silent Night! www.stillenacht.com Holy Night! English Salzburg Oberndorf Arnsdorf Austria’s Hallein message of peace Hintersee to the world Wagrain September 29, 2018 – Mariapfarr February 3, 2019 Hochburg-Ach Fügen im Zillertal www.landesausstellung2018.at City of Salzburg Salzburg Museum Silent Night 200 – History. Message. Presence. Joseph Mohr was born to an unwed mother on December 11, 1792, in Salzburg and baptized in the Salzburg Cathedral. Recognizing the young man’s talent, the vicar of the cathedral choir took Mohr under his wing, helping him with his educa- tion and fi nally his career as a priest. In 1816, he penned the lyrics to the song while on his fi rst assignment in Mariapfarr. Mohr met Franz Xaver Gruber, a teacher from Arnsdorf and the compos- er of the melody, when he moved to Oberndorf in 1817. Together they performed the song for the very fi rst time. This special exhibition touches on the history, message, and the continuing pres- ence of this world-renowned song. The exhibition is divided into six themes: the history of the song, the life stories of its creators, Mohr and Gruber, the tradition and distribution of the song, and the political and commercial instrumentalization. Salzburg Museum Neue Residenz Mozartplatz 1, 5010 Salzburg Information and guided tours: +43 662 620808-200 offi [email protected] www.salzburgmuseum.at Opening hours: Tue. – Sun. 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m (Christmas opening hours on the website in December) © SLTG/Salzburg Museum © SLTG/Salzburg Manufacturer: Druckerei Roser GmbH, Hallwang. Misprints and printing errors reserved. -

“White Christmas”—Bing Crosby (1942) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Cary O’Dell

“White Christmas”—Bing Crosby (1942) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Cary O’Dell Crosby’s 1945 holiday album Original release label “Holiday Inn” movie poster With the possible exception of “Silent Night,” no other song is more identified with the holiday season than “White Christmas.” And no singer is more identified with it than its originator, Bing Crosby. And, perhaps, rightfully so. Surely no other Christmas tune has ever had the commercial or cultural impact as this song or sold as many copies--50 million by most estimates, making it the best-selling record in history. Irving Berlin wrote “White Christmas” in 1940. Legends differ as to where and how though. Some say he wrote it poolside at the Biltmore Hotel in Phoenix, Arizona, a reasonable theory considering the song’s wishing for wintery weather. Some though say that’s just a good story. Furthermore, some histories say Berlin knew from the beginning that the song was going to be a massive hit but another account says when he brought it to producer-director Mark Sandrich, Berlin unassumingly described it as only “an amusing little number.” Likewise, Bing Crosby himself is said to have found the song only merely adequate at first. Regardless, everyone agrees that it was in 1942, when Sandrich was readying a Christmas- themed motion picture “Holiday Inn,” that the song made its debut. The film starred Fred Astaire and Bing Crosby and it needed a holiday song to be sung by Crosby and his leading lady, Marjorie Reynolds (whose vocals were dubbed). Enter “White Christmas.” Though the film would not be seen for many months, millions of Americans got to hear it on Christmas night, 1941, when Crosby sang it alone on his top-rated radio show “The Kraft Music Hall.” On May 29, 1942, he recorded it during the sessions for the “Holiday Inn” album issued that year. -

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows As of 01-01-2003

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows as of 01-01-2003 $64,000 Question, The 10-2-4 Ranch 10-2-4 Time 1340 Club 150th Anniversary Of The Inauguration Of George Washington, The 176 Keys, 20 Fingers 1812 Overture, The 1929 Wishing You A Merry Christmas 1933 Musical Revue 1936 In Review 1937 In Review 1937 Shakespeare Festival 1939 In Review 1940 In Review 1941 In Review 1942 In Revue 1943 In Review 1944 In Review 1944 March Of Dimes Campaign, The 1945 Christmas Seal Campaign 1945 In Review 1946 In Review 1946 March Of Dimes, The 1947 March Of Dimes Campaign 1947 March Of Dimes, The 1948 Christmas Seal Party 1948 March Of Dimes Show, The 1948 March Of Dimes, The 1949 March Of Dimes, The 1949 Savings Bond Show 1950 March Of Dimes 1950 March Of Dimes, The 1951 March Of Dimes 1951 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1951 March Of Dimes On The Air, The 1951 Packard Radio Spots 1952 Heart Fund, The 1953 Heart Fund, The 1953 March Of Dimes On The Air 1954 Heart Fund, The 1954 March Of Dimes 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air With The Fabulous Dorseys, The 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1954 March Of Dimes On The Air 1955 March Of Dimes 1955 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1955 March Of Dimes, The 1955 Pennsylvania Cancer Crusade, The 1956 Easter Seal Parade Of Stars 1956 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 Heart Fund, The 1957 March Of Dimes Galaxy Of Stars, The 1957 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 March Of Dimes Presents The One and Only Judy, The 1958 March Of Dimes Carousel, The 1958 March Of Dimes Star Carousel, The 1959 Cancer Crusade Musical Interludes 1960 Cancer Crusade 1960: Jiminy Cricket! 1962 Cancer Crusade 1962: A TV Album 1963: A TV Album 1968: Up Against The Establishment 1969 Ford...It's The Going Thing 1969...A Record Of The Year 1973: A Television Album 1974: A Television Album 1975: The World Turned Upside Down 1976-1977. -

The English Listing

THE CROSBY 78's ZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBAthe English listing Members may recall that we issued a THE questionnaire in 1990 seeking views and comments on what we should be providing in CROSBY BING. We are progressively attempting to fulfil 7 8 's these wishes and we now address one major ENGLISH request - a listing of the 78s issued in the UK. LISTING The first time this listing was issued in this form was in the ICC's 1974 booklet and this was updated in 1982in a publication issued by John Bassett's Crosby Collectors Society. The joint compilers were Jim Hayes, Colin Pugh and Bert Bishop. John has kindly given us permission to reproduce part of his publication in BING. This is a complete listing of very English-issued lO-inch and 12-inch 78 rpm shellac record featuring Sing Crosby. In all there are 601 discs on 10different labels. The sheet music used to illustrate some of the titles and the photos of the record labels have been p ro v id e d b y Don and Peter Haizeldon to whom we extend grateful thanks. NUMBERSITITLES LISTING OF ENGLISH 78"s ARIEl GRAND RECORD. THE 110-Inchl 4364 Susiannainon-Bing BRUNSWICK 112-inchl 1 0 5 Gems from "George White's Scandals", Parts 1 & 2 0 1 0 5 ditto 1 0 7 Lawd, you made the night too long/non-Bing 0 1 0 7 ditto 1 1 6 S I. L o u is blues/non-Bing _ 0 1 3 4 Pennies from heaven medley/Pennies from heaven THECROSBYCOLLECTORSSOCIETY BRUNSWICK 110-inchl 1 1 5 5 Just one more chance/Were you sincere? 0 1 6 0 8 Home on the range/The last round-up 0 1 1 5 5 ditto 0 1 6 1 5 Shadow waltz/I've got to sing a torch -

How to Make 1981/1 Silent Night Fabric Advent Calendar

How To Make 1981/1 Silent Night Fabric Advent Calendar Make a pretty advent calendar that will hold treats and surprises year after year, as it becomes part of your family’s Christmas traditions. Watch our free instructional video on You Tube http://www.youtube.com/user/makoweruk 1981/1 Silent Night Advent Calendar Panel Requirements Quantity 1981/1 Makower Advent Panel 60cms / 24” Coordinating Backing Fabric (70 cm x 112cm / 27.5” x 45”) Wadding (70 cm x 112cm / 27.5” x 45”) Thread to match Unit 14, Cordwallis Business Park, Clivemont Road, Maidenhead, Berkshire SL6 7BU +44(0)1628 509640 [email protected] www.makoweruk.com Sewing Instructions For Advent Calendar Make these easy to construct advent calendars and fill them with your own choice of sweets and treats for Christmas. Wendy Gardiner provides some simple steps and tips to make up the panels easily and quickly. 1. Cut out the panel around the border. Next cut out the pockets, cutting along the solid lines only. 2. On each pocket strip fold under the top edge to the wrong side and press in place. 3. Using the edge of the presser foot as a guide for the edge of the fabric, move the needle across to the right with the stitch width button and top stitch the turned edge of pocket strips in place. 4. Press the stitched tops. 5. To make the box pleats, pinch a fold in the pocket edge and fold it towards the blue dotted line and press in place. Repeat for the other side, and pin in place so that the folds at the bottom of the pockets are butted against each other. -

Ilfilfihletter

P.O. Box 240 Ojai Calif. ilfilfihletter 93024—O24-O May 1990 Vol. 9 N0. 5 Baker of the New York Times wrote that a more appropriate Mail Bag response from George Bush would have been something to the effect of "I have more important things on my mind." The last person I ever expected to read about in your other- wise very special Jazzletter is Roseanne Barr. Quel dommage. Gene Lees’ attack on The Star Spangled Banner is way off Ernie Furtado, New York City key. He makes the mistake of allowing his dissatisfaction with I agree, with delight! I’ve long been musically embarrassed those abominable lyrics to color his opinion of the melody, by The Star Spangled Banner, even though I still feel vestiges which in itself is perfectly adequate or better. When Sarah of pompous pride stir in my blood when I’m required to play Vaughan sang The Star Spangled Banner, it became a thing of it. (The bass line is better than the melody.) After all, I sang beauty -- especially if you didn’t understand English. It did1i’t it daily as an innocent school child, with a good singing voice, matter to her that the song is rangy, nor should Gene have .might add. I was always the one in every group who could allowed this to confuse his judgment of the melody. Did sing the whole thing right. The song came to represent my anyone ever complain that Memories of You was beyond the home connection, even though I always loved America the capability of many singers because of its range? And how Beautifizl more as a song and as a poem. -

Exit Here for Jazz…

Volume 43 • Issue 11 December 2015 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. Pianist Marc Cary, center, is flanked by members of his Harlem Sessions All-Stars during their performance at the Exit 0 Jazz Festival in Cape May on Nov. 7. Photo by Mitchell Seidel. Exit Here For Jazz… Now in its 4th year, Exit 0, the new iteration of a twice-yearly Cape May jazz festival, expands its soul and R&B offerings (and its audience) while still serving up plenty of outstanding straight-ahead and trad jazz. Jersey Jazz’s Mitchell Seidel offers an inside view in words and pictures beginning on page 26. New JerseyJazzSociety in this issue: New Jersey Jazz socIety Prez Sez. 2 Bulletin Board ......................2 NJJS Calendar ......................3 Jazz Trivia .........................4 In The Mailbag. .4 Prez Sez Editor’s Pick/Deadlines/NJJS Info .......6 Crow’s Nest. 46 By Mike Katz President, NJJS Change of Address/Support NJJS/ Volunteer/Join NJJS. 47 USPS Statement of Ownership ........47 NJJS/Pee Wee T-shirts. 48 nce again, the holiday season is upon us! For are selected by the Music Committee, but it has New/Renewed Members ............48 Othe New Jersey Jazz Society, that means become a tradition that the President selects the storIes (among other things) it’s time for the annual group to perform at the annual meeting. For this Exit 0 Jazz Festival ..............cover meeting, at which the officers report on the state of year’s meeting, I have picked the DIVA Jazz Trio, Big Band in the Sky ..................8 the society and leadership is elected for the coming consisting of Sherrie Maricle on drums, Tomoko Talking Jazz: Ted Nash ..............12 year. -

How to Order by Phone Call the Hal Leonard E-Z Order Line at 1-800-554-0626, Monday Through Friday Between 8:30 A.M

HOW TO ORDER By Phone Call the Hal Leonard E-Z Order Line at 1-800-554-0626, Monday through Friday between 8:30 a.m. and 9:00 p.m. or Saturday and Sunday 9:00 a.m. - 5:00 C.S.T. Please have ready the following information: • Your customer account number • Your purchase order number • Special shipping instructions (if any) • Quantity of each item • Hal Leonard inventory number of each item (the 8-digit number listed with all products) By Fax You may fax your order to 414-774-3259. Be sure to put “Attention: Sales” on your cover page, and include all of the same information listed under the “By Phone” section. By E-Mail Simply e-mail us at [email protected] with the same information as above. By Mail For stock orders, simply indicate the quantity of each item you wish to order directly in this catalog and mail it back to us. A Hal Leonard sales representative will be happy to provide you with a replacement catalog. On Line Visit Hal Leonard on the internet at http://www.halleonard.com/dealers. Ask your sales rep about our dealer access web features. International Orders For international inquiries, please contact the Hal Leonard International Sales Department at [email protected]. Canadian Dealers, please contact the Sales Representative for Canada at [email protected]. Customer Service Should you have any questions regarding your account (shipping, orders, etc.), please call our Customer Service Department in Winona, Minnesota, toll-free at 1-800-321-3408 Monday through Friday between 8:00 a.m. -

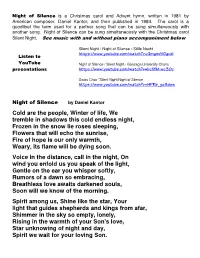

Night of Silence Is a Christmas Carol and Advent Hymn, Written in 1981 by American Composer, Daniel Kantor, and Then Published in 1984

Night of Silence is a Christmas carol and Advent hymn, written in 1981 by American composer, Daniel Kantor, and then published in 1984. The carol is a quodlibet the term used for a partner song that can be sung simultaneously with another song. Night of Silence can be sung simultaneously with the Christmas carol Silent Night. See music with and without piano accompaniment below Silent Night - Night of Silence - Stille Nacht https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qmgnx5OgvsI Listen to YouTube Night of Silence / Silent Night - Gonzaga University Choirs presentations https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bcXfM-wc30c Swiss Choir "Silent Night/Night of Silence https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HPRb_yo9dow Night of Silence by Daniel Kantor Cold are the people, Winter of life, We tremble in shadows this cold endless night, Frozen in the snow lie roses sleeping, Flowers that will echo the sunrise, Fire of hope is our only warmth, Weary, its flame will be dying soon. Voice in the distance, call in the night, On wind you enfold us you speak of the light, Gentle on the ear you whisper softly, Rumors of a dawn so embracing, Breathless love awaits darkened souls, Soon will we know of the morning. Spirit among us, Shine like the star, Your light that guides shepherds and kings from afar, Shimmer in the sky so empty, lonely, Rising in the warmth of your Son's love, Star unknowing of night and day, Spirit we wait for your loving Son. SSSSttttiiiilllllllleeee NNNNaaaacccchhhhtttt SSSSiiiilllleeeennnntttt NNNNiiiigggghhhhtttt Composer Franz Xaver Gruber (1787-1863) John Freeman Young (verses 1-3), ca. -

Jimmy Durante Papers PASC-M.0195

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8cv4m1z No online items Finding Aid for the Jimmy Durante Papers PASC-M.0195 Finding aid prepared by Alexandra Apolloni; machine-readable finding aid created by Julie Graham and Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2021 January 19. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Jimmy Durante PASC-M.0195 1 Papers PASC-M.0195 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Jimmy Durante papers Creator: Durante, Jimmy Identifier/Call Number: PASC-M.0195 Physical Description: 150 Linear Feet(342 boxes) Date (inclusive): circa 1920s-circa 1990 Abstract: Jimmy Durante had a decades-long career as a musician, songwriter, comedian, and actor. The collection consists of script material, scrapbooks, photographs, written music, audio recordings, printed material and ephemera, and a small amount of correspondence documenting Durante's extensive career as an entertainer on stage, radio, film, and television. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Physical Characteristics and Technical Requirements CONTAINS AUDIOVISUAL MATERIALS: This collection contains both processed and unprocessed audiovisual materials. Audiovisual materials are not currently available for access, unless otherwise noted in a Physical Characteristics and Technical Requirements note at the series and file levels. -

Les Brown and His Band of Renown Best of the Capitol Years Mp3, Flac, Wma

Les Brown And His Band Of Renown Best Of The Capitol Years mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Best Of The Capitol Years Country: US Released: 2002 Style: Big Band, Swing MP3 version RAR size: 1119 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1994 mb WMA version RAR size: 1572 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 263 Other Formats: ASF AU MOD DMF FLAC MMF MP2 Tracklist 1 I've Got My Love To Keep Me Warm 2 On The Alamo 3 Perfidia 4 Moonlight In VBermont 5 The Continental 6 Midnight Sun 7 Lover 8 Harlem Nocturne 9 The Piccolino 10 Shine On Harvest Moon 11 Tangerine 12 Ridin' High 13 Nina Never Knew 14 My Blue Heaven 15 Stardust 16 Tea For Two 17 Swingin' Down The Line 18 Younger Than Spring Time 19 This Nearly Was Mine 20 Invitation 21 The Sweetheart Of Sigma Chi 22 Frenesi 23 Just You, Just Me 24 Leap Frog 25 Goodnight Sweetheart Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Capitol Records, Inc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Capitol Records, Inc. Copyright (c) – Capitol Records, Inc. Credits Arranged By – Frank Comstock (tracks: 2 to 4, 6 to 8, 11 to 13, 17, 19 to 25), J. Hill (tracks: 10, 14 to 16), Les Brown (tracks: 18), Skip Martin (tracks: 1, 5, 9), Sonny Burke (tracks: 18) Notes (p) & (C) 2002 Captol Records Inc. All Tracks 24-Bit Digitally Remastered All tracks previously released: Tracks 1, 6, 20 & 24 rec. December 1958 (The Les Brown Sory) Tracks 2, 3, 7, 11 & 22 rec. May 1955 (Dance To The Bands / Band Of Renown Joins The Capitol Label [EP]) Tracks 4, 5, 8, 9,, 123, & 13 rec.