'A Deconstructed Shrine': Locating Absence and Relocating Identity In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London Metropolitan Archives Spitalfields

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 SPITALFIELDS MARKET CLA/013 Reference Description Dates ADMINISTRATION General administration CLA/013/AD/01/001 Particulars of auction sales held by Messrs. Oct 1931 - Mar Lyons Son & Co. (Fruit Brokers) Ltd. 1934 1 volume CLA/013/AD/01/002 Case of Mayor & c. v. Lyons Son & Co. (Fruit 1932 - 1935 Brokers) Ltd. High Court of Justice - Chancery Division Statement of Claim 1932, concerning auction sales. Defence 1932 Reply [of Plaintiffs] 1932 Answer of Plaintiffs to Interrogatories 1933 Defence and Counterclaim 1933 Amended Reply [of Plaintiffs] 1933 Evidence of Major Millman, the Clerk and Superintendent of the Market, 28 March 1934 (refers to London Fruit Exchange and methods of working) Proof of evidence, with index Transcript of Judgment 1934 Also Mayor & c. v. Lyons Son & Co. Court of Appeal. Transcript of Judgment 1935 With Case for the Opinion of Counsel and Counsel's Opinion re Markets Established By Persons Without Authority (Northern Market Authorities Assoc./Assoc. of Midland Market Authorities 1 file LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 SPITALFIELDS MARKET CLA/013 Reference Description Dates CLA/013/AD/01/003 Case of Mayor & c v. Lyons Son & Co. 1933 - 1934 Judgment of Mr Justice Luxmoore in Chancery Division as to the limits of Spitalfields Market and the right of the public to sell by auction in the Market so long as there is room. 30th Nov. 1934. (Copies) Translation of Charter of 29th July 34 Charles II. (1682) Translation of Charter of 6th March 1 Edw. III (1326/7) Translation of Charter of 26th May 15 Edw. -

Future of New Spitalfields Market

Bringing the Wholesale Markets Together Future of New Spitalfields Market Image of the existing New Spitalfields Market site. The City of London Corporation At this very early stage the City of has plans to move New Spitalfields London is seeking initial feedback from New website Market in Leyton to a new site in local communities on our vision for the the London Borough of Barking future of the markets before plans are We have launched a new website: brought forward. In this newsletter you and Dagenham. wholesalemarkets.co.uk. can find out more about: This will be the central source of This will help to protect the future of Our early vision for the new markets information about the plans for the the market for generations to come co-location of New Spitalfields (fruit and open up the existing site for How you can provide your comments & vegetables), Billingsgate (fish) redevelopment opportunities that could The next steps for the project and Smithfield (meat) markets to help to meet the need for new housing Dagenham Dock. and workspaces for Londoners. About New Spitalfields Market Located in Leyton since the early some parts of the building are already 1990’s in Waltham Forest, New outdated and there is not enough room for Spitalfields is Britain’s premier tenants to store and display their produce. wholesale fruit, vegetable and Further, the restrictive site design, which has no unloading bays or delivery docks, flower market. creates substantial operating challenges, Along with the City of London’s two other including conflicts between pedestrians wholesale food markets at Billingsgate and forklift truck drivers, which drive and Smithfield, the market has been at through the main market floor. -

J103917 Principal Place Broch

THE SHARD THE CITY CORE LIVERPOOL SPITALFIELDS STREET STATION 01 Introduction WELCOME TO THE WEST SIDE On the border of the fast-paced hub of the City and the creative buzz of Shoreditch, Principal Place, a vibrant mixed-use development by Brookfield, is perfectly placed to enjoy the rich variety of opportunities offered by this thriving business location. Amazon, the world’s largest online retailer, has already chosen it as their new home, taking 518,000 sq ft. Now The West Side, Principal Place, with its own dramatic entrance and atrium, offers a further 81,000 sq ft of prime office accommodation and the chance to join an illustrious commercial neighbourhood. — HELLO _THE WEST SIDE CGI of the Piazza at Principal Place Local Area 04 ISLINGTON N TREET OLD S S FLOWER H O MARKET R E D I T C H H I OLD G H STREET ET S TRE T OLD S R E E G T RE BETHNAL GREEN RD AT E AS PRIME POSITION TE R N ST Between the solid tradition of the RE B ET SCLATER ST R I C Bank of England and the innovating SHOREDITCH K C L I D A T HIGH STREET A N Y O technologies of Silicon Roundabout, E R R N I O A E T A T The West Side at Principal Place R D U A C G L C offers the best of all worlds. O O F M WEST SIDE N M O E T R Shoreditch is transforming on an R C O IA N L S almost weekly basis, as Michelin- T R E E T starred restaurants, cool clubs, visionary galleries and high-end CH brands set up shop alongside the ISWELL ST area’s historic markets and long D A O R established East End businesses. -

Shoreditch Spitalfields Walk for JF

Hoxton Shoreditch Spitalfields Walk 0.5 kilometre N Ion D A Square St John s O R Gardens Hoxton IA B M U L O D C HOXTON LE ST U NDA R BAXE A N T T S B LT O S A WIMB R T Ravenscroft N E Gardens Jesus Green T 19 T D REE ST A ILTER QU G O W R RO R O ON V T T S G E D LLIN ROA WE T BIA E LUM SS CO O G S Aske Q U Gdns 20 I Old D R N R A I E T Magistrates L S E 10 S 32 E HOXTON S Court G T R S T SQUARE N D I T OR K S B D M R S HA D A AUST I W C L OLD ST IN S IN TR G A E EET R I I V N 56 S F F H CHARLES T Old 3 I I HOXTON E Buses 8, 388 to pub O C SQUARE P St Leonard s L MKT 2 R AD T H Town D Liverpool Street RO S N OOT ST E EN WI B A Shoreditch RE LD 125- D G BA R Hall T HNAL I ARNOLD L T S ET CA Y B O 130 B C L VERT CIRCUS ISS U T H AVE AL C T P 2 E T K GTON S Boundary ST IN RIV F E H HIR S T S A YS S I Gardens RB T T E G S D RIVINGTON ST C D L R T H M O U V E St Matthew s Weavers S 18-26 R S 0 A pub A E T T T T T 4 1 L OLD ST STA. -

{FREE} Londons Markets : from Smithfield to Portobello Road Pdf

LONDONS MARKETS : FROM SMITHFIELD TO PORTOBELLO ROAD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Stephen Halliday | 192 pages | 01 Jun 2014 | The History Press Ltd | 9780752494487 | English | Stroud, United Kingdom Londons Markets : From Smithfield to Portobello Road PDF Book Entry fee applies. Czech Republic. We have a fresh supply of our traditional English tea pots, cups and jugs, planters and gardening giftware and of course our handmade glass baubles. The original site still houses Old Spitalfields Market , a continuous rotation of arts, crafts, antiques, record fairs, vintage fairs, and street food. Monday- Saturday, 10am-5pm. As well as the up-and-coming designers that are supported here, you can also nab yourself some serious high fashion if you rummage around enough. The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Julie Falconer aladyinlondon. Monday-Saturday, 9am-6pm. Feeling peckish? Product Category. While many London markets have reopened with safety measures in place following the coronavirus lockdown , some remain closed or have restricted opening times. London Paperbacks. In form the Meat Market is a parallelogram. Save on Nonfiction Trending price is based on prices over last 90 days. Keep track of everything you watch; tell your friends. Regents Park is around 10 mins away by foot, while the famous Madame Tussauds museum is around 15 minutes' walk away. The cruelties inflicted are "pething," hitting them over the horns, and "hocking. You can find almost anything at the market; think of any ingredient and you will find it here. Privacy Policy. Brick Lane Upmarket. By Laura Reynolds. Edit page. -

01 Pages 1&2

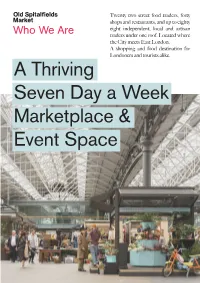

Twenty two street food traders, forty shops and restaurants, and up to eighty eight independent, local and artisan Who We Are traders under one roof. Located where the City meets East London. A shopping and food destination for Londoners and tourists alike. A Thriving Seven Day a Week Marketplace & Event Space www.oldspitalfieldsmarket.com Old Spitalfields Market is Location located five minutes walk from Liverpool Street Station, with up to 180,000 people passing through each week. Hackney King’s Cross Hoxton King’s Cross Angel Shoreditch High Street Old Street Farringdon Bethnal Green Tottenham Oxford Court Road Circus Whitechapel Soho Liverpool Street Covent Garden Mayfair Waterloo Westminster London Bridge Victoria Elephant & Castle Bermodsey Southwark Lambeth Brick Lane Peckham Camberwell 2 mins walk Vauxhall Shoreditch High Street 3 mins walk Liverpool Street 5 mins walk Oxford Circus 13 mins tube + walk Weekdays 20,000 Daily Visitors City workers Young Professionals Tourists Weekends 40,000 Daily Visitors Tourists Locals & Families Social Media 76,000 Followers* 33,500 30,000 14,000 Footfall & Demographics Nine Million People Visit Old Spitalfields Market Every Year www.oldspitalfieldsmarket.com * April 2019 Brand Promotion & Events The Space... Gateway Sampling Team Away Days Talks Market Takeovers Workshops Cinema Street Food Client Entertaining Image credit: LCF x Microsoft at London College of Fashion, UAL. Brand Promotion & Events Gate 5 Lamb Street Gate 6 Gate 4 1 Market Floor Event Space (a) Commercial Street Commercial Gate 4 3 Mezzanine 2 Event Space Gate Market Floor 7 Event Space (b) Gate 2 4 3 4 3 Gate Gate 8 1 Brushfield Street 1 Market Floor Event Space 3 Gateway Sampling 2 Mezzanie Event Space 4 Branded Installation Locations www.oldspitalfieldsmarket.com Brand Promotion & Events 1. -

New Spitalfields Market

NEW SPITALFIELDS MARKET New Spitalfields 2010 (v3).indd 1 11/29/2010 3:47:05 PM TYDENE Purveyors Of Quality Fruit And Vegetables New Spitalfields Stand 5/6 020 8558 8047 Tydene is one of UK’s largest fresh produce supplier. Tydene is a complete fresh produce solution provider that sources, imports, packages, distributes and markets over elds Market 200 lines of fresh fruit and vegetables to the wholesale and retail trades. Our extensive seasonal range of fruit and vegetables is testament to our commitment. High Quality Products From The Farm... To Your Table New Spitalfi elds Market Sherrin Road Spitalfi New (Off Ruckholt Road) Leyton, London Index E10 5SQ United Kingdom Message From Superintendent ......................................... 5 Tel 020 8518 7670 Fax 020 8518 7449 Foreword From Tenants Association Chairman ................ 7 About New Spitalfi elds Market ......................................... 8 Hygience, Tours & Visits........................................................................ 11 Years Quality History of New Spitalfi elds Market .................................... 14 of Tenants & Traders - Market Hall .......................................... 22 & No part of this publication may be copied or reproduced, in any Experience Trust form or by any means, electronic, Cafes / Importers / Services ............................................... 30 mechanical, photocopy or otherwise without the express permission of the publishers. How To Find Us ................................................................... 34 -

Beyond Banglatown Continuity, Change and New Urban Economies in Brick Lane

Runnymede Perspectives Beyond Banglatown Continuity, change and new urban economies in Brick Lane Claire Alexander, Seán Carey, Sundeep Lidher, Suzi Hall and Julia King Runnymede: Acknowledgements The ‘Beyond Banglatown’ team would like to thank all Intelligence for a Multi- of the business owners, restaurateurs and stakeholders who have taken part in this project. We would also like to ethnic Britain thank the AHRC (Arts and Humanities Research Council) for its continued support, and the Runnymede Trust for its continued collaboration on this work. Thanks to Feedback Runnymede is the UK’s Films and Millipedia for their work on the film and the website leading independent thinktank that accompany this publication. on race equality and race Thanks to the project advisory board for their guidance relations. Through high- throughout the project: quality research and thought Bashir Ahmed Rob Berkeley leadership, we: Aditya Chakrabortty Joya Chatterji • Identify barriers to race Richard Derecki Unmesh Desai equality and good race Kate Gavron relations; Omar Khan • Provide evidence to Chris Orme Ben Rogers support action for social change; Special thanks to Shams Uddin for all the time he gave to us, • Influence policy at all and to Raju Vaidyanathan for his wonderful photographs. levels. ISBN: 978-1-909546-34-9 Published by Runnymede in July 2020, this document is copyright © Runnymede 2020. Some rights reserved. Open access. Some rights reserved. The Runnymede Trust wants to encourage the circulation of its work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. The trust has an open access policy which enables anyone to access its content online without charge. -

Further Information a Walk in Spitalfields

Walk Further information 5 A walk in For more detailed information take a look at www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/data/discover Spitalfields Places to go, things to do To find out more about eating, drinking and shopping in Spitalfields look for the Secrets of to the right. This pub is close to the 18th Century Stop and look at number 4 Fournier Street (14), which Cross Commercial Street at the Ten Bells pub (16) to get Spitalfields Guide or visit Truman’s brewery complex (10), the chimney of was built in 1726 by Marmaduke Smith, a local carpenter, to Spitalfields Market. The pub is so named because Christ www.spitalfields.org.uk which can be seen from the street. The brewery brewed as his own residence. The front of the house is framed by Church originally had only one bell; more bells were added beer from 1666 to 1989 and is now a haven for small two brick pilasters, and the door case, more typical of the as competition started with St Brides, Fleet Street over who Eating and Drinking designer and media businesses and is also home to two of period than Hawksmoor next door, has brackets carved had the finest peal of bells. When the church Give your taste buds a treat in the many London’s trendiest nightspots – 93 Feet East and The Vibe with ears of wheat and scallop shells. The scallop shells commissioned its tenth bell the pub became known as the restaurants, bars and pubs. To find out more Bar. Spitalfields was popular with brewers, as there is a refer to the pilgrim badge of St James and are the 18th Ten Bells. -

Businesses Operating at New Spitalfields Market

City of London Corporation, New Spitalfields Market 14-18 Allen House, 23 Sherrin Road, London E10 5SQ T. +44 (0)20 8518 7670 (option 3) E. [email protected] W. www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/spitalfields Businesses operating at New Spitalfields Market Market wholesalers Name Premises Products Phone Fax Email/website/social media A1 Veg Ltd Stands 69 & 70 Fruit & vegetables 020 8988 0111 020 8556 0234 [email protected] www.a1veg.com Aberdeen & Stanton Stand 67 Vegetables & herbs 020 8556 3128 020 8558 8935 [email protected] Ltd Ahmed Exotics Stand 38 Asian fruits & 020 8518 7008 020 8539 7757 [email protected] vegetables Akbar General Stand 71 Ethnic Asian fruit & 020 8558 7418 020 8558 7410 [email protected] Importers vegetables Alancia Fruit & Veg Stands 83a & 83b Onions, potatoes, 020 8539 0165 020 8988 0833 n/a garlic, ginger & salad Amer Superfresh Stands 93a & 108 Fruit & vegetables 020 8556 0101 020 8556 0419 [email protected] Anika Fruit & Veg Stand 10 Tomatoes, coriander, 020 8988 0681 n/a [email protected] spinach, jack fruit, www.anikafnvltd.co.uk ginger, garlic & pineapple Bala Impex Stands 76 & 77 Indian vegetables 020 8558 5874 020 8558 1915 n/a Booker Hart Ltd Stands 1a, 19 & 20 British potatoes, 020 8539 8787 n/a [email protected] parsnips, carrots & onions Braund; Walter Stand 62 Fruit 020 8558 9868 020 8558 7062 [email protected] Braund (Spitalfields) www.walterbraund.co.uk Ltd Stand Bristow; R J Bristow & Stands 93b & 109 Fresh flowers, foliage, 020 8558 6655 n/a [email protected] Son house/garden & www.facebook.com/Rjbandsons plants/shrubs. -

New Spitalfields Market Tenants Listing

New Spitalfields Market Tenants Listing KEY ORGANISATIONS THE CITY OF LONDON CORPORATION 14-18 Allen House Tel: 020 8518 7670 Fax: 020 8518 7449 Email: [email protected] SPITALFIELDS MARKET TENANTS ASSOCIATION Offices 5 & 6 Allen House Tel: 020 8556 1479 Fax: 020 8556 1033 Email: [email protected] RURAL PAYMENTS AGENCY Office 1, 1st Floor Allen House Tel: 020 8539 6147 Fax: 020 8539 7128 Email: [email protected] Web: www.rpa.gov.uk UNITE UNION Mr Ricky Thomas Tel: 07957 713929 1 COMPANY CONTACT DETAILS PRODUCE TYPE A1 VEG LTD T: 020 8988 0111 Fruit and vegetables Stands 69 & 70 F: 020 8556 0234 ABERDEEN & STANTON LTD T: 020 8556 3128 Fruit, vegetables and salad Stand 67 F: 020 8558 8935 E: [email protected] AHMED EXOTICS T: 020 8518 7008 Vegetables Stand 38 F: 020 8539 7757 E: [email protected] AKBAR GENERAL IMPORTERS T: 020 8558 7418 Ethnic Asian fruit and Stand 71 F: 020 8558 7410 vegetables E: [email protected] ALANCIA FRUIT & VEG T: 020 8539 0165 Onions, potatoes, garlic, Stands 83a & 83b F: 020 8988 0833 ginger and salad AMER SUPERFRESH T: 020 8556 0101 Coriander, herbs, spinach, Stands 93a & 108 F: 020 8556 0419 fruit and vegetables E: [email protected] BALA IMPEX T: 020 8558 5874 Indian vegetables Stands 76-77 F: 020 8558 1915 BOOKER HART LTD T: 020 8539 8787 British potatoes, parsnips, Stands 1a, 19 & 20 F: 020 8539 7236 carrots and onions BRAUND; WALTER BRAUND (SPITALFIELDS) LTD T: 020 8558 9868 Fruit Stand 62 F: 020 8558 7062 BRISTOW; R J BRISTOW & SON T: -

Changing London 12 07 Changing London Changing London

07 Changing London 12 07 Changing London Changing London AN HISTORIC CITY FOR A MODERN WORLD NEXT ISSUE SAVING LONDON LONDON’S SPORTING HERITAGE MARKETS WHAT HAS BEEN HAPPENING WITH SOME OF With the 2012 Olympics being held in London, LONDON’S HISTORIC BUILDINGS we will be looking at the wide variety of Reminders of London’s ancient markets are all But it is not only in the centre of London that historic buildings and sites associated with around in the capital’s street names: medieval markets add to the character of an area. Across sport in the capital down the centuries. Cheapside, 17th century Haymarket, 18th the city, around one hundred general and century Shepherd Market… specialist markets of all sorts bring life and Markets have always had an impact on vitality to our streets, often reflecting something London’s built environment.The splendid of the nature of the communities in which they Billingsgate market hall designed by Horace have developed. New markets, such as the Jones in 1874 is a reminder of the area’s burgeoning ‘Farmers’ Markets’, bring a temporary association with fish (and bad language!) even village air to several London neighbourhoods. though the market itself moved to the Isle of In this issue of Changing London we look at Dogs in 1982.The attractive Victorian market this rich and diverse aspect of the capital. buildings of Leadenhall and Smithfield are still in use, although there are concerns about the future of Smithfield. SPITALFIELDS CHARNEL HOUSE BRUSHFIELD STREET In advance of major redevelopment of the western area of the former Spitalfields horticultural market, archaeological investigation unearthed the substantial remains of a 14th century charnel house associated with the priory of St Mary Spital.