THE MARKET PLACE and the MARKET's PLACE in LONDON, C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking the Borough Market Route: an Experimental Ethnography of the Marketplace

Taking the Borough Market Route: An Experimental Ethnography of the Marketplace Freek Janssens -- 0303011 Freek.Janssens©student.uva.nl June 2, 2008 Master's thesis in Cultural An thropology at the Universiteit van Amsterdam. Committee: dr. Vincent de Rooij (supervi sor), prof. dr. Johannes Fabian and dr. Gerd Baumann. The River Tharrws and the Ciiy so close; ihis mnst be an important place. With a confident but at ihe same time 1incertain feeling, I walk thrmigh the large iron gales with the golden words 'Borough Market' above il. Asphalt on the floor. The asphalt seems not to correspond to the classical golden letters above the gate. On the right, I see a painted statement on the wall by lhe market's .mpcrintendent. The road I am on is private, it says, and only on market days am [ allowed here. I look around - no market to sec. Still, I have lo pa8s these gales to my research, becanse I am s·upposed to meet a certain Jon hCTe today, a trader at the market. With all the stories I had heard abont Borongh Market in my head, 1 get confnsed. There is nothing more to see than green gates and stalls covered with blue plastic sheets behind them. I wonder if this can really turn into a lively and extremely popular market during the weekend. In the corner I sec a sign: 'Information Centre. ' There is nobody. Except from some pigeons, all I see is grey walls, a dirty roof, gates, closed stalls and waste. Then I see Jon. A man in his forties, small and not very thin, walks to me. -

Town Tree Cover in Bridgend County Borough

1 Town Tree Cover in Bridgend County Borough Understanding canopy cover to better plan and manage our urban trees 2 Foreword Introducing a world-first for Wales is a great pleasure, particularly as it relates to greater knowledge about the hugely valuable woodland and tree resource in our towns and cities. We are the first country in the world to have undertaken a country-wide urban canopy cover survey. The resulting evidence base set out in this supplementary county specific study for Bridgend County Borough will help all of us - from community tree interest groups to urban planners and decision-makers in local Emyr Roberts Diane McCrea authorities and our national government - to understand what we need to do to safeguard this powerful and versatile natural asset. Trees are an essential component of our urban ecosystems, delivering a range of services to help sustain life, promote well-being, and support economic benefits. They make our towns and cities more attractive to live in - encouraging inward investment, improving the energy efficiency of buildings – as well as removing air borne pollutants and connecting people with nature. They can also mitigate the extremes of climate change, helping to reduce storm water run-off and the urban heat island. Natural Resources Wales is committed to working with colleagues in the Welsh Government and in public, third and private sector organisations throughout Wales, to build on this work and promote a strategic approach to managing our existing urban trees, and to planting more where they will -

Sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science, 1904–2015 Christopher T

Sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science, 1904–2015 Christopher T. Husbands Sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science, 1904–2015 Sound and Fury Christopher T. Husbands Emeritus Reader in Sociology London School of Economics and Political Science London, UK Additional material to this book can be downloaded from http://extras.springer.com. ISBN 978-3-319-89449-2 ISBN 978-3-319-89450-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89450-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018950069 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and trans- mission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Directory of London and Westminster, & Borough of Southwark. 1794

Page 1 of 9 Home Back Directory of London and Westminster, & Borough of Southwark. 1794 SOURCE: Kent's Directory for the Year 1794. Cities of London and Westminster, & Borough of Southwark. An alphabetical List of the Names and Places of Abode of the Directors of Companies, Persons in Public Business, Merchts., and other eminent Traders in the Cities of London and Westminster, and Borough of Southwark. Dabbs Tho. & John, Tanners, Tyre's gateway, Bermondsey st. Dacie & Hands, Attornies, 30, Mark lane Da Costa Mendes Hananel, Mercht. 2, Bury str. St. Mary-ax Da Costa & Jefferson, Spanish Leather dressers, Bandy leg walk, Southwark Da Costa J. M. sen. India Agent & Broker, 2, Bury street, St. Mary- ax, or Rainbow Coffee house Daintry, Ryle & Daintry, Silkmen, 19, Wood street Daker Joseph, Buckram stiffner, 14, Whitecross street Dakins & Allinson, Wholesale Feather dealers, 23, Budge row Dalby John, Fellmonger, Old Ford Dalby John, Goldsmith & Jeweller, 105, New Bond street Dalby Wm. Linen draper, 25, Duke street, Smithfield Dalby & Browne, Linen drapers, 158, Leadenhall street Dale E. Wholesale Hardware Warehouse, 49, Cannon street Dale George, Sail maker, 72, Wapping wall Dale J. Musical Instrument maker, 19, Cornhill, & 130, Oxford str. Dale John, Biscuit baker, 3, Shadwell dock Dalgas John, Broker, 73, Cannon street Dallas Robert, Insurance broker, 11, Mincing lane Dallisson Thomas, Soap maker, 149, Wapping Dalston Wm. Grocer & Brandy Mercht. 7, Haymarket Dalton James, Grocer & Tea dealer, Hackney Dalton & Barber, Linen drapers, 28, Cheapside Daly & Pickering, Ironmongers, &c. 155, Upper Thames str. Dalzell A. Wine, Spirit & Beer Mercht. 4, Gould sq. Crutched-f. Danby Michael, Ship & Insurance broker, Virginia Coffee house, Cornhill Dangerfield & Lum, Weavers, 17, Stewart street, Spitalfields Daniel Edward, Tea dealer, Southampton street, Strand Daniel & Co. -

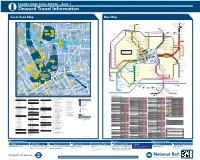

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 1 35 Wellington OUTRAM PLACE 259 T 2 HAVELOCK STREET Caledonian Road & Barnsbury CAMLEY STREET 25 Square Edmonton Green S Lewis D 16 L Bus Station Games 58 E 22 Cubitt I BEMERTON STREET Regent’ F Court S EDMONTON 103 Park N 214 B R Y D O N W O Upper Edmonton Canal C Highgate Village A s E Angel Corner Plimsoll Building B for Silver Street 102 8 1 A DELHI STREET HIGHGATE White Hart Lane - King’s Cross Academy & LK Northumberland OBLIQUE 11 Highgate West Hill 476 Frank Barnes School CLAY TON CRESCENT MATILDA STREET BRIDGE P R I C E S Park M E W S for Deaf Children 1 Lewis Carroll Crouch End 214 144 Children’s Library 91 Broadway Bruce Grove 30 Parliament Hill Fields LEWIS 170 16 130 HANDYSIDE 1 114 CUBITT 232 102 GRANARY STREET SQUARE STREET COPENHAGEN STREET Royal Free Hospital COPENHAGEN STREET BOADICEA STREE YOR West 181 212 for Hampstead Heath Tottenham Western YORK WAY 265 K W St. Pancras 142 191 Hornsey Rise Town Hall Transit Shed Handyside 1 Blessed Sacrament Kentish Town T Hospital Canopy AY RC Church C O U R T Kentish HOLLOWAY Seven Sisters Town West Kentish Town 390 17 Finsbury Park Manor House Blessed Sacrament16 St. Pancras T S Hampstead East I B E N Post Ofce Archway Hospital E R G A R D Catholic Primary Barnsbury Handyside TREATY STREET Upper Holloway School Kentish Town Road Western University of Canopy 126 Estate Holloway 1 St. -

The Blitz and Its Legacy

THE BLITZ AND ITS LEGACY 3 – 4 SEPTEMBER 2010 PORTLAND HALL, LITTLE TITCHFIELD STREET, LONDON W1W 7UW ABSTRACTS Conference organised by Dr Mark Clapson, University of Westminster Professor Peter Larkham, Birmingham City University (Re)planning the Metropolis: Process and Product in the Post-War London David Adams and Peter J Larkham Birmingham City University [email protected] [email protected] London, by far the UK’s largest city, was both its worst-damaged city during the Second World War and also was clearly suffering from significant pre-war social, economic and physical problems. As in many places, the wartime damage was seized upon as the opportunity to replan, sometimes radically, at all scales from the City core to the county and region. The hierarchy of plans thus produced, especially those by Abercrombie, is often celebrated as ‘models’, cited as being highly influential in shaping post-war planning thought and practice, and innovative. But much critical attention has also focused on the proposed physical product, especially the seductively-illustrated but flawed beaux-arts street layouts of the Royal Academy plans. Reconstruction-era replanning has been the focus of much attention over the past two decades, and it is appropriate now to re-consider the London experience in the light of our more detailed knowledge of processes and plans elsewhere in the UK. This paper therefore evaluates the London plan hierarchy in terms of process, using new biographical work on some of the authors together with archival research; product, examining exactly what was proposed, and the extent to which the different plans and different levels in the spatial planning hierarchy were integrated; and impact, particularly in terms of how concepts developed (or perhaps more accurately promoted) in the London plans influenced subsequent plans and planning in the UK. -

The Custom House

THE CUSTOM HOUSE The London Custom House is a forgotten treasure, on a prime site on the Thames with glorious views of the river and Tower Bridge. The question now before the City Corporation is whether it should become a luxury hotel with limited public access or whether it should have a more public use, especially the magnificent 180 foot Long Room. The Custom House is zoned for office use and permission for a hotel requires a change of use which the City may be hesitant to give. Circumstances have changed since the Custom House was sold as part of a £370 million job lot of HMRC properties around the UK to an offshore company in Bermuda – a sale that caused considerable merriment among HM customs staff in view of the tax avoidance issues it raised. SAVE Britain’s Heritage has therefore worked with the architect John Burrell to show how this monumental public building, once thronged with people, can have a more public use again. SAVE invites public debate on the future of the Custom House. Re-connecting The City to the River Thames The Custom House is less than 200 metres from Leadenhall Market and the Lloyds Building and the Gherkin just beyond where high-rise buildings crowd out the sky. Who among the tens of thousands of City workers emerging from their offices in search of air and light make the short journey to the river? For decades it has been made virtually impossible by the traffic fumed canyon that is Lower Thames Street. Yet recently for several weeks we have seen a London free of traffic where people can move on foot or bike without being overwhelmed by noxious fumes. -

Different Faces of One ‘Idea’ Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek

Different faces of one ‘idea’ Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek To cite this version: Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek. Different faces of one ‘idea’. Architectural transformations on the Market Square in Krakow. A systematic visual catalogue, AFM Publishing House / Oficyna Wydawnicza AFM, 2016, 978-83-65208-47-7. halshs-01951624 HAL Id: halshs-01951624 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01951624 Submitted on 20 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Architectural transformations on the Market Square in Krakow A systematic visual catalogue Jean-Yves BLAISE Iwona DUDEK Different faces of one ‘idea’ Section three, presents a selection of analogous examples (European public use and commercial buildings) so as to help the reader weigh to which extent the layout of Krakow’s marketplace, as well as its architectures, can be related to other sites. Market Square in Krakow is paradoxically at the same time a typical example of medieval marketplace and a unique site. But the frontline between what is common and what is unique can be seen as “somewhat fuzzy”. Among these examples readers should observe a number of unexpected similarities, as well as sharp contrasts in terms of form, usage and layout of buildings. -

The Burlington Arcade Would Like to Welcome You to a VIP Invitation with One of London’S Luxury Must-See Shopping Destinations

The Burlington Arcade would like to welcome you to a VIP Invitation with one of London’s luxury must-see shopping destinations BEST OF BRITISH SUPERIOR LUXURY SHOPPING SERVICE & England’s oldest and longest shopping BEADLES arcade, open since 1819, The Burlington TOURS Arcade is a true luxury landmark in London. The Burlington Beadles Housing over 40 specialist shops and are the knowledgeable designer brands including Lulu Guinness uniformed guards and Jimmy Choo’s only UK menswear of the Arcade ȂƤǡ since 1819. They vintage watches, bespoke footwear and the conduct pre-booked Ƥ Ǥ historical tours of the Located discreetly between Bond Street Arcade for visitors and and Piccadilly, the Arcade has long been uphold the rules of the favoured by Royalty, celebrities and the arcade which include prohibiting the opening of cream of British society. umbrellas, bicycles and whistling. The only person who has been given permission to whistle in the Arcade is Sir Paul McCartney. HOTEL GUEST BENEFITS ǤǡƤ the details below and hand to the Burlington Beadles when you visit. They will provide you with the Burlington VIP Card. COMPLIMENTARY VIP EXPERIENCES ơ Ǥ Pre-booked at least 24 hours in advance. Ƥǣ ǡ the expert consultants match your personality to a fragrance. This takes 45 minutes and available to 1-6 persons per session. LADURÉE MACAROONS ǣ Group tea tasting sessions at LupondeTea shop can Internationally famed for its macaroons, Ǧ ơ Parisian tearoom Ladurée, lets you rest and Organic Tea Estate. revive whilst enjoying the surroundings of the To Pre-book simply contact Ellen Lewis directly on: beautiful Arcade. -

Parking Information

Parking Information WHERE TO Visiting Old Billingsgate? PARK While there is no on-site parking at Old Billingsgate, there are ample parking opportunities at nearby car parks. The car parks nearest to the venue are detailed below: Tower Hill Corporation of London Car and Coach Park 50 Lower Thames Street (opposite Sugar Quay), EC3R 6DT 250m, 4 minute walk Monday - Friday 06:00 - 19:00 £3.50 per hour (for cars) Open 24 hrs, 7 days a week (including bank holidays) Saturday 06:00 - 13:30 £3.50 per hour (for cars) Number of Spaces: 110 cars / 16 coaches / 0 All other times £3.50 per visit commercial / 13 disabled (for cars) bays £10 per hour (for coaches) Free motorcycle and pedal cycle parking areas Overnight parking 17:00 - 09:00 capped at £25 (for coaches) London Vintry Thames Exchange – NCP Thames Exchange, Bell Wharf Lane, EC4R 3TB 0.4 miles, 8 minute walk 1 hour £3.20 Open 24 hrs, 7 days week 1 - 2 hours £6.40 (including bank holidays) 3 - 4 hours £12.80 Number of Spaces: 466 cars / 0 commercial / 5 - 6 hours £19.20 2 disabled bays 9 - 24 hours £32 Motorcycles £6.50 per day OLD BILLINGSGATE London Finsbury Square – NCP (Commercial Vehicle Parking) Finsbury Square, Finsbury, London, EC2A 1AD 1.1 miles, 22 minute walk 1 hour £5 Open 24 hrs, 7 days week 1 - 2 hours £10 (including bank holidays) 2 - 4 hours £18 Number of Spaces: 258 cars / 8 commercial / 2 4 - 24 hour £26 disabled bays Motorcycles £6 per day On-Street Bicycle Parking There are 40+ on-street cycle spaces within 5 minutes walk of Old Billingsgate. -

U DPC Papers of Philip Corrigan Relating 1919-1973 to the London School of Economics

Hull History Centre: Papers of Philip Corrigan relating to the London School of Economics U DPC Papers of Philip Corrigan relating 1919-1973 to the London School of Economics Historical background: Philip Corrigan? The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a specialist social science university. It was founded in 1894 by Beatrice and Sidney Webb. Custodial History: Donated by Philip Corrigan, Department of Sociology and Social Administration, Durham University, October 1974 Description: Material about the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) including files relating to the history of the institution, and miscellaneous files referring to accounts, links with other countries, particularly Southern Rhodesia, and aspects of student militancy and student unrest. Arrangement: U DPC/1-8 Materials (mainly photocopies) for a history of the London School of Economics and Political Science, 1919- 1973 U DPC/9-14 Miscellaneous files relating to LSE and higher education, 1966-1973 Extent: 0.5 linear metres Access Conditions: Access will be given to any accredited reader page 1 of 8 Hull History Centre: Papers of Philip Corrigan relating to the London School of Economics U DPC/1 File. 'General; foundation; the Webbs' containing the 1919-1970 following items relating to the London School of Economics and Political Science: (a) Booklist and notes (4pp.). No date (b) 'The London School of Economics and Political Science' by D. Mitrany ('Clare Market Review Series', no.1, 1919) (c) Memorandum and Articles of Association of the LSE, dated 1901, reprinted 1923. (d) 'An Historical Note' by Graham Wallas ('Handbook of LSE Students' Union', 1925, pp.11-13) (e) 'Freedom in Soviet Russia' by Sidney Webb ('Contemporary Review', January 1933, pp.11-21) (f) 'The Beginnings of the LSE'' by Max Beer ('Fifty Years of International Socialism', 1935, pp.81-88) (g) 'Graduate Organisations in the University of London' by O.S. -

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British