Bazaars and Bazaar Buildings in Regency and Victorian London’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buses from Knightsbridge

Buses from Knightsbridge 23 414 24 Buses towardsfrom Westbourne Park BusKnightsbridge Garage towards Maida Hill towards Hampstead Heath Shirland Road/Chippenham Road from stops KH, KP From 15 June 2019 route 14 will be re-routed to run from stops KB, KD, KW between Putney Heath and Russell Square. For stops Warren towards Warren Street please change at Charing Cross Street 52 Warwick Avenue Road to route 24 towards Hampstead Heath. 14 towards Willesden Bus Garage for Little Venice from stop KB, KD, KW 24 from stops KE, KF Maida Vale 23 414 Clifton Gardens Russell 24 Square Goodge towards Westbourne Park Bus Garage towards Maida Hill 74 towards Hampstead HeathStreet 19 452 Shirland Road/Chippenham Road towards fromtowards stops Kensal KH, KPRise 414From 15 June 2019 route 14from will be stops re-routed KB, KD to, KW run from stops KB, KD, KW between Putney Heath and Russell Square. For stops Finsbury Park 22 TottenhamWarren Ladbroke Grove from stops KE, KF, KJ, KM towards Warren Street please change atBaker Charing Street Cross Street 52 Warwick Avenue Road to route 24 towards Hampsteadfor Madame Heath. Tussauds from 14 stops KJ, KM Court from stops for Little Venice Road towards Willesden Bus Garage fromRegent stop Street KB, KD, KW KJ, KM Maida Vale 14 24 from stops KE, KF Edgware Road MargaretRussell Street/ Square Goodge 19 23 52 452 Clifton Gardens Oxford Circus Westbourne Bishop’s 74 Street Tottenham 19 Portobello and 452 Grove Bridge Road Paddington Oxford British Court Roadtowards Golborne Market towards Kensal Rise 414 fromGloucester stops KB, KD Place, KW Circus Museum Finsbury Park Ladbroke Grove from stops KE23, KF, KJ, KM St. -

Star Wars at MT

NEW STAR WARS AT MADAME TUSSAUDS UNIQUE INTERACTIVE STAR WARS EXPERIENCE OPENS MAY 2015 A NEW multi-million pound experience opens at Madame Tussauds London in May, with a major new interactive Star Wars attraction. Created in close collaboration with Disney and Lucasfilm, the unique, immersive experience brings to life some of film’s most powerful moments featuring extraordinarily life- like wax figures in authentic walk-in sets. Fans can star alongside their favourite heroes and villains of Star Wars Episodes I-VI, with dynamic special effects and dramatic theming adding to the immersion as they encounter 16 characters in 11 separate sets. The attraction takes the Madame Tussauds experience to a whole new level with an experience that is about much more than the wax figures. Guests will become truly immersed in the films as they step right into Yoda's swamp as Luke Skywalker did in Star Wars: Episode V The Empire Strikes Back or feel the fiery lava of Mustafar as Anakin turns to the dark side in Star Wars: Episode III Revenge of the Sith. Spanning two floors, the experience covers a galaxy of locations from the swamps of Dagobah and Jabba’s Throne Room to the flight deck of the Millennium Falcon. Fans can come face-to-face with sinister Stormtroopers; witness Luke Skywalker as he battles Darth Vader on the Death Star; feel the Force alongside Obi-Wan Kenobi and Qui-Gon Jinn when they take on Darth Maul on Naboo; join the captive Princess Leia and the evil Jabba the Hutt in his Throne Room; and hang out with Han Solo in the cantina before stepping onto the Millennium Falcon with the legendary Wookiee warrior, Chewbacca. -

Mystery on Baker Street

MYSTERY ON BAKER STREET BRUTAL KAZAKH OFFICIAL LINKED TO £147M LONDON PROPERTY EMPIRE Big chunks of Baker Street are owned by a mysterious figure with close ties to a former Kazakh secret police chief accused of murder and money-laundering. JULY 2015 1 MYSTERY ON BAKER STREET Brutal Kazakh official linked to £147m London property empire EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The ability to hide and spend suspect cash overseas is a large part of what makes serious corruption and organised crime attractive. After all, it is difficult to stuff millions under a mattress. You need to be able to squirrel the money away in the international financial system, and then find somewhere nice to spend it. Increasingly, London’s high-end property market seems to be one of the go-to destinations to give questionable funds a veneer of respectability. It offers lawyers who sell secrecy for a living, banks who ask few questions, top private schools for your children and a glamorous lifestyle on your doorstep. Throw in easy access to anonymously-owned offshore companies to hide your identity and the source of your funds and it is easy to see why Rakhat Aliyev. (Credit: SHAMIL ZHUMATOV/X00499/Reuters/Corbis) London’s financial system is so attractive to those with something to hide. Global Witness’ investigations reveal numerous links This briefing uncovers a troubling example of how between Rakhat Aliyev, Nurali Aliyev, and high-end London can be used by anyone wanting to hide London property. The majority of this property their identity behind complex networks of companies surrounds one of the city’s most famous addresses, and properties. -

Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East

Viewpoints Special Edition Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East The Middle East Institute Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints is another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US relations with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org Cover photos, clockwise from the top left hand corner: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Imre Solt; © GFDL); Tripoli, Libya (Patrick André Perron © GFDL); Burj al Arab Hotel in Dubai, United Arab Emirates; Al Faisaliyah Tower in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Doha, Qatar skyline (Abdulrahman photo); Selimiye Mosque, Edirne, Turkey (Murdjo photo); Registan, Samarkand, Uzbekistan (Steve Evans photo). -

Timeline: 2-14 Baker Street Date Event Notes

Timeline: 2-14 Baker Street Parties: British Land, McAleer & Rushe. Bank of Ireland, NAMA, Portman Estate Topic: 2-14 Baker Street - in London which was subject to a loan from Bank of Ireland Timeline: Date Event Notes August Several media articles report on This was the second reported purchase by and agreement between British Land and McAleer & Rushe from British Land – the September McAleer & Rushe for the sale (by BL) previous deal was for the Swiss Centre in 2005 of 2-14 Baker Street. Leicester Square. Guide price for the 2-14 Baker Street property was UK£47.5m with British Land offering it as a potential 150,000 sq. ft development opportunity. 5th 2-14 Baker Street purchased by Travers Smith acted for McAleer & Rushe October McAleer & Rushe by British Land for Group on the acquisition. 2005 UK£57.2m. The existing building tenants: Purchase funded with a Bank of Offices let on a lease expiring in December Ireland loan. 2009. Retail accommodation let under four separate leases all expiring by December 2009 The property comprised 94,000 sq. ft. held on a 98 year headlease from the Portman Estate. 16th Planning Application submitted to Planning application filed by Gerald Eve, December Westminster City Council listing Chartered Surveyors and Property Consultants 2008 Owners pf 2-14 Baker Street as: Contact person: James Owens 1. Portman Estate (freeholder) [email protected] 2. Mourant & Co Trustees Ltd and Mourant Property Trustees Ltd Baker Street Unit Trust is owned by McAleer & as Trustees of the Baker Street Rushe with a Jersey address. -

Different Faces of One ‘Idea’ Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek

Different faces of one ‘idea’ Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek To cite this version: Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek. Different faces of one ‘idea’. Architectural transformations on the Market Square in Krakow. A systematic visual catalogue, AFM Publishing House / Oficyna Wydawnicza AFM, 2016, 978-83-65208-47-7. halshs-01951624 HAL Id: halshs-01951624 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01951624 Submitted on 20 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Architectural transformations on the Market Square in Krakow A systematic visual catalogue Jean-Yves BLAISE Iwona DUDEK Different faces of one ‘idea’ Section three, presents a selection of analogous examples (European public use and commercial buildings) so as to help the reader weigh to which extent the layout of Krakow’s marketplace, as well as its architectures, can be related to other sites. Market Square in Krakow is paradoxically at the same time a typical example of medieval marketplace and a unique site. But the frontline between what is common and what is unique can be seen as “somewhat fuzzy”. Among these examples readers should observe a number of unexpected similarities, as well as sharp contrasts in terms of form, usage and layout of buildings. -

The Burlington Arcade Would Like to Welcome You to a VIP Invitation with One of London’S Luxury Must-See Shopping Destinations

The Burlington Arcade would like to welcome you to a VIP Invitation with one of London’s luxury must-see shopping destinations BEST OF BRITISH SUPERIOR LUXURY SHOPPING SERVICE & England’s oldest and longest shopping BEADLES arcade, open since 1819, The Burlington TOURS Arcade is a true luxury landmark in London. The Burlington Beadles Housing over 40 specialist shops and are the knowledgeable designer brands including Lulu Guinness uniformed guards and Jimmy Choo’s only UK menswear of the Arcade ȂƤǡ since 1819. They vintage watches, bespoke footwear and the conduct pre-booked Ƥ Ǥ historical tours of the Located discreetly between Bond Street Arcade for visitors and and Piccadilly, the Arcade has long been uphold the rules of the favoured by Royalty, celebrities and the arcade which include prohibiting the opening of cream of British society. umbrellas, bicycles and whistling. The only person who has been given permission to whistle in the Arcade is Sir Paul McCartney. HOTEL GUEST BENEFITS ǤǡƤ the details below and hand to the Burlington Beadles when you visit. They will provide you with the Burlington VIP Card. COMPLIMENTARY VIP EXPERIENCES ơ Ǥ Pre-booked at least 24 hours in advance. Ƥǣ ǡ the expert consultants match your personality to a fragrance. This takes 45 minutes and available to 1-6 persons per session. LADURÉE MACAROONS ǣ Group tea tasting sessions at LupondeTea shop can Internationally famed for its macaroons, Ǧ ơ Parisian tearoom Ladurée, lets you rest and Organic Tea Estate. revive whilst enjoying the surroundings of the To Pre-book simply contact Ellen Lewis directly on: beautiful Arcade. -

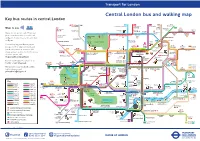

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

Revitalization of the Bazaar Neighborhood in Tehran

REVITALIZATION OF THE BAZAAR NEIGHBORHOOD IN TEHRAN BY PARDIS MOINZADEH THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Landscape Architecture in Landscape Architecture in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign , 2014 Urbana, Illinois Adviser: P Professor D. Fairchild Ruggles Abstract The word “bazaar” comes from an ancient word “wazaar” meaning market. The word “baza” has been used in other countries such as Turkey, Arabic countries and India as well.1 Bazaars are historic market places that provide trade services as well as other functions. Their historic buildings are renowned for their architectural aesthetics, and in old cities such as Tehran (Iran) they are considered the centerpiece of activities with architectural, cultural, historical, religious, and commercial values. However, during the past 400 years, they have undergone social and environmental changes. The neighborhood of the Tehran Bazaar has in recent decades become degraded, which has consequently decreased the social value of the historic Bazaar. The ruined urban condition makes it impossible for contemporary visitors to have a pleasurable experience while visiting the Bazaar, although that was historically their experience. As Tehran began to grow, much of the trade and finance in the city has moved to the newly developed section of the city, diminishing the importance of the bazaars. Today, shoppers and residents living in the Bazaar neighborhood inhabit dilapidated buildings, while customers and tourists—when they go there at all—experience a neighborhood that lacks even the most basic urban amenities such as sidewalks, drainage, benches, trees and lighting. This design study required a number of investigations. -

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time and Text Ashley D. Polasek Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY awarded by De Montfort University December 2014 Faculty of Art, Design, and Humanities De Montfort University Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 Theorising Character and Modern Mythology ............................................................ 1 ‘The Scarlet Thread’: Unraveling a Tangled Character ...........................................................1 ‘You Know My Methods’: Focus and Justification ..................................................................24 ‘Good Old Index’: A Review of Relevant Scholarship .............................................................29 ‘Such Individuals Exist Outside of Stories’: Constructing Modern Mythology .......................45 CHAPTER ONE: MECHANISMS OF EVOLUTION ............................................. 62 Performing Inheritance, Environment, and Mutation .............................................. 62 Introduction..............................................................................................................................62 -

The Change of the Hospital Architecture from the Early Part of 20Th Century to Nowadays: an Example of Konya

New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences Volume 4, Issue 11, (2017) 23-34 ISSN:2547-8818 www.prosoc.eu Selected Paper of 6th World Conference on Design and Arts (WCDA 2017), 29 June – 01 July 2017, University of Zagreb, Zagreb – Croatia The Change of the Hospital Architecture from the Early Part of 20th Century to Nowadays: An Example of Konya Dicle Aydin a*, Department of Architecture, Necmettin Erbakan University, 42090 Konya, Turkey. Esra Yaldiz b, Department of Architecture, Necmettin Erbakan University, 42090 Konya, Turkey. Suheyla Buyuksahin c, Department of Architecture, Selcuk University, 42075 Konya, Turkey. Suggested Citation: Aydin, D., Yaldiz, E. & Buyuksahin, S. (2017). The change of the hospital architecture from the early part of 20th century to nowadays: an example of Konya. New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences. [Online]. 4(11), 23-34. Available from: www.prosoc.eu Selection and peer review under responsibility of Prof. Dr. Ayse Cakir Ilhan, Ankara University, Turkey. ©2017 SciencePark Research, Organization & Counseling. All rights reserved. Abstract The hospitals that served in the name of ‘darussifa’ in Seljuk Empire period in Anatolia continued their service during Ottoman Empire period. The health institutions in different areas in Ottoman period were replaced by ‘Gureba hospitals’ in 19th century. The change in Anatolia was realised, after the declaration of the Republic and with the development of its economy, and lived in every area; hospital buildings were constructed first as ‘Gureba hospitals’ then as ‘country hospitals’ in Anatolia cities like Konya after the big cities like İstanbul, Ankara and İzmir. -

Apartments Mixes the Best of Contemporary Urban Living with the Grand Traditions of Historic Victorian Design

DISCOVER THE ATELIER A sophisticated haven in the heart of London’s prestigious West Kensington, The Atelier is where refi nement and relaxation go hand in hand. This unique collection of stylish, characterful apartments mixes the best of contemporary urban living with the grand traditions of historic Victorian design. From its private landscaped courtyard gardens to its distinguished architecture, it’s a building that impresses. Just minutes from the centre of London, the rich history, landmark buildings and tranquil green spaces give it an air of grandeur where it’s easy to feel at home. The Atelier - an address to be proud of. THE ATELIER EXTERIORS BRITISH HERITAGE WITH STYLE More than any other neighbourhood in this most historic city, Kensington is known for the elegance of its historic buildings. It’s where the Victorian architecture of London is at its most striking with row after row of characterful streets. Sinclair Road is one of the more delightful and is where The Atelier will sit, in an area that exudes peacefulness. Blending in perfectly with its surroundings while making a quiet statement of its own, The Atelier mixes the traditional and contemporary with stunning results. Evocative London brick façades with horizontal banding, impressive bay windows and mansard roofs combine to make this a building worthy of its address. Most importantly, with its landscaped courtyard gardens, underground parking, on site gym, friendly concierge and even its own cinema, it’s a place to call home. Computer generated image 4 5 THE ATELIER “ A private and secluded sanctuary in the middle of the exclusive Kensington community, The Atelier will sit proudly in this historic neighbourhood.” Computer generated image 6 7 THE ATELIER LONDON SCHOOL CITY OF ROYAL ALBERT HOUSES OF CANARY IMPERIAL OF ECONOMICS LONDON HALL PARLIAMENT WHARF COLLEGE LONDON KENSINGTON KYOTO BT HYDE HOLLAND KING'S ST.