Cardinal Reginald Pole: Questions of Self-Justification and of Faith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beware of False Shepherds, Warhs Hem. Cardinal

Member of Audit Bureau of Circulations Principals in Pallium Ceremony i * BEWARE OF FALSE SHEPHERDS, % WARHS HEM. CARDINAL STRITCH Contonto Copjrrighted by the Catholic Preas Society, Inc. 1946— Pemiosion to reproduce, Except on Articles Otherwise Marke^ given After 12 M. Friday Following Issue Traces Catastrophes DENVER OONOLIC Of Modern Society To Godless Leaders I ^ G I S T E R Sermon al Pallium Ceremony in Denver Cathe The National Catholic Welfare Conference News Service Supplies The Denver Catholic Register. We dral Shows How Archbishop Shares in Have Also the International Nows Service (Wire and Mail), a Large Special Service, Seven Smaller Services, Photo Features, and Wide World Photos. (3 cents per copy) True Pastoral Office VOL. XU. No. 35. DENVER, COLO., THURSDAY, A PR IL 25, 1946. $1 PER YEAR Beware of false shepherds who scoff at God, call morality a mere human convention, and use tyranny and persecution as their staff. There is more than a mere state ment of truth in the words of Christ: “I am the Good Shep Official Translation of Bulls herd.” There is a challenge. Other shepherds offer to lead men through life but lead men astray. Christ is the only shepherd. Faithfully He leads men to God. This striking comparison of shepherds is the theme Erecting Archdiocese Is Given of the sermon by H. Em. Cardinal Samuel A. Stritch of Chicago in the Solemn Pon + ' + + tifical Mass in the Deliver Ca An official translation of the PERPETUAL MEMORY OF THE rate, first of all, the Diocese of thedral this Thursday morning, Papal Bulls setting up the Arch EVENT Denver, together with its clergy April 25, at which the sacred pal diocese of Denver in 1941 was The things that seem to be more and people, from the Province of lium is being conferred upon Arch Bishop Lauds released this week by the Most helpful in procuring the greater Santa Fe. -

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and The

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and the Limits of Control in the Information Age Jan W Geisbusch University College London Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Anthropology. 15 September 2008 UMI Number: U591518 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591518 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration of authorship: I, Jan W Geisbusch, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature: London, 15.09.2008 Acknowledgments A thesis involving several years of research will always be indebted to the input and advise of numerous people, not all of whom the author will be able to recall. However, my thanks must go, firstly, to my supervisor, Prof Michael Rowlands, who patiently and smoothly steered the thesis round a fair few cliffs, and, secondly, to my informants in Rome and on the Internet. Research was made possible by a grant from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). -

Acollection of Correspondence

© 2012 Capuchin Friars of Australia. All Rights Reserved. A COLLECTION OF CORRESPONDENCE Some Letters … and other things, from Sixteenth Century Italy in their original languages Bernardo, ben potea bastarvi averne Co’l dolce dir, ch’a voi natura infonde, Qui dove ‘l re de’ fiume ha più chiare onde, Acceso i cori a le sante opre eterne; Ché se pur sono in voi pure l’interne Voglie, e la vita al destin corrisponde, Non uom di frale carne e d’ossa immonde, Ma sète un voi de le schiere sperne. Or le finte apparenze, e ‘l ballo, e ‘l suono, Chiesti dal tempo e da l’antica usanza, A che così da voi vietate sono? Non fôra santità,capdox fôra arroganza Tôrre il libero arbitrio, il maggior dono Che Dio ne diè ne la primera stanza.1 Compiled by Paul Hanbridge Fourth edition, formerly “A Sixteenth Century Carteggio” Rome, 2007, 2008, Dec 2009 1 “Bernardo, it should be enough for you / With that sweet speech infused in you by Nature, / To light our hearts to high eternal works, / Here where the King of Rivers flows most clearly. / Since your own inner wishes are sincere, / And your own life reflects a pure intent, / You’re ra- ther an inhabitant of heaven. /As to these masquerades, dances, and music, /Sanctioned by time and by ancient custom - /Why do you now forbid them in your sermons? /Holiness it is not, but arrogance to take away free will, the highest gift/ Which God bestowed on us from the begin- ning.” Tullia d’Aragona (c. -

Scenario Book 1

Here I Stand SCENARIO BOOK 1 SCENARIO BOOK T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S ABOUT THIS BOOK ......................................................... 2 Controlling 2 Powers ........................................................... 6 GETTING STARTED ......................................................... 2 Domination Victory ............................................................. 6 SCENARIOS ....................................................................... 2 PLAY-BY-EMAIL TIPS ...................................................... 6 Setup Guidelines .................................................................. 2 Interruptions to Play ............................................................ 6 1517 Scenario ...................................................................... 3 Response Card Play ............................................................. 7 1532 Scenario ...................................................................... 4 DESIGNER’S NOTES ........................................................ 7 Tournament Scenario ........................................................... 5 EXTENDED EXAMPLE OF PLAY................................... 8 SETTING YOUR OWN TIME LIMIT ............................... 6 THE GAME AS HISTORY................................................. 11 GAMES WITH 3 TO 5 PLAYERS ..................................... 6 CHARACTERS OF THE REFORMATION ...................... 15 Configurations ..................................................................... 6 EVENTS OF THE REFORMATION -

Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform

6 RENAISSANCE HISTORY, ART AND CULTURE Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform of Politics Cultural the and III Paul Pope Bryan Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Renaissance History, Art and Culture This series investigates the Renaissance as a complex intersection of political and cultural processes that radiated across Italian territories into wider worlds of influence, not only through Western Europe, but into the Middle East, parts of Asia and the Indian subcontinent. It will be alive to the best writing of a transnational and comparative nature and will cross canonical chronological divides of the Central Middle Ages, the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. Renaissance History, Art and Culture intends to spark new ideas and encourage debate on the meanings, extent and influence of the Renaissance within the broader European world. It encourages engagement by scholars across disciplines – history, literature, art history, musicology, and possibly the social sciences – and focuses on ideas and collective mentalities as social, political, and cultural movements that shaped a changing world from ca 1250 to 1650. Series editors Christopher Celenza, Georgetown University, USA Samuel Cohn, Jr., University of Glasgow, UK Andrea Gamberini, University of Milan, Italy Geraldine Johnson, Christ Church, Oxford, UK Isabella Lazzarini, University of Molise, Italy Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Bryan Cussen Amsterdam University Press Cover image: Titian, Pope Paul III. Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy / Bridgeman Images. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 252 0 e-isbn 978 90 4855 025 8 doi 10.5117/9789463722520 nur 685 © B. -

Cardinal Cajetan Renaissance Man

CARDINAL CAJETAN RENAISSANCE MAN William Seaver, O.P. {)T WAS A PORTENT of things to come that St. Thomas J Aquinas' principal achievement-a brilliant synthesis of faith and reason-aroused feelings of irritation and confusion in most of his contemporaries. But whatever their personal sentiments, it was altogether too imposing, too massive, to be ignored. Those committed to established ways of thought were startled by the revolutionary character of his theological entente. William of la Mare, a representa tive of the Augustinian tradition, is typical of those who instinctively attacked St. Thomas because of the novel sound of his ideas without taking time out to understand him. And the Dominicans who rushed to the ramparts to vindicate a distinguished brother were, as often as not, too busy fighting to be able even to attempt a stone by stone ex amination of the citadel they were defending. Inevitably, it has taken many centuries and many great minds to measure off the height and depth of his theological and philosophical productions-but men were ill-disposed to wait. Older loyalities, even in Thomas' own Order, yielded but slowly, if at all, and in the midst of the confusion and hesitation new minds were fashioning the via moderna. Tempier and Kilwardby's official condemnation in 1277 of philosophy's real or supposed efforts to usurp theology's function made men diffident of proving too much by sheer reason. Scotism now tended to replace demonstrative proofs with dialectical ones, and with Ockham logic and a spirit of analysis de cisively supplant metaphysics and all attempts at an organic fusion between the two disciplines. -

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Abbreviations Used ....................................................................................................... 4 3 Archbishops of Canterbury 1052- .................................................................................. 5 Stigand (1052-70) .............................................................................................................. 5 Lanfranc (1070-89) ............................................................................................................ 5 Anselm (1093-1109) .......................................................................................................... 5 Ralph d’Escures (1114-22) ................................................................................................ 5 William de Corbeil (1123-36) ............................................................................................. 5 Theobold of Bec (1139-61) ................................................................................................ 5 Thomas Becket (1162-70) ................................................................................................. 6 Richard of Dover (1174-84) ............................................................................................... 6 Baldwin (1184-90) ............................................................................................................ -

Giuseppe Maria Abbate the Italian-American Celestial Messenger

Magnus Lundberg & James W. Craig Jim W Giuseppe Maria Abbate The Italian-American Celestial Messenger Uppsala Studies in Church History 7 1 About the Series Uppsala Studies in Church History is a series that is published in the Department of Theology, Uppsala University. It includes works in both English and Swedish. The volumes are available open-access and only published in digital form, see www.diva-portal.org. For information on the individual titles, see the last page of this book. About the authors Magnus Lundberg is Professor of Church and Mission Studies and Acting Professor of Church History at Uppsala University. He specializes in early modern and modern church and mission history with a focus on colonial Latin America, Western Europe and on contemporary traditionalist and fringe Catholicism. This is his third monograph in the Uppsala Studies in Church History Series. In 2017, he published A Pope of Their Own: Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church and Tomás Ruiz: Utbildning, karriär och konflikter i den sena kolonialtidens Centralamerika. The Rev. Father James W. Craig is a priest living in the Chicagoland area. He has a degree in History from Northeastern Illinois University and is a member of Phi Alpha Theta the national honor society for historians. He was ordained to the priesthood of the North American Old Roman Catholic Church in 1994 by the late Archbishop Theodore Rematt. From the time he first started hearing stories of the Celestial Father he became fascinated with the life and legacy of Giuseppe Maria Abbate. He is also actively involved with the website Find a Grave, to date having posted over 31,000 photos to the site and creating over 12,000 memorials to commemorate the departed. -

![List 3-2016 Accademia Della Crusca – Aldine Device 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5354/list-3-2016-accademia-della-crusca-aldine-device-1-bardi-giovanni-1534-1612-465354.webp)

List 3-2016 Accademia Della Crusca – Aldine Device 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]

LIST 3-2016 ACCADEMIA DELLA CRUSCA – ALDINE DEVICE 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]. Ristretto delle grandeze di Roma al tempo della Repub. e de gl’Imperadori. Tratto con breve e distinto modo dal Lipsio e altri autori antichi. Dell’Incruscato Academico della Crusca. Trattato utile e dilettevole a tutti li studiosi delle cose antiche de’ Romani. Posto in luce per Gio. Agnolo Ruffinelli. Roma, Bartolomeo Bonfadino [for Giovanni Angelo Ruffinelli], 1600. 8vo (155x98 mm); later cardboards; (16), 124, (2) pp. Lacking the last blank leaf. On the front pastedown and flyleaf engraved bookplates of Francesco Ricciardi de Vernaccia, Baron Landau, and G. Lizzani. On the title-page stamp of the Galletti Library, manuscript ownership’s in- scription (“Fran.co Casti”) at the bottom and manuscript initials “CR” on top. Ruffinelli’s device on the title-page. Some foxing and browning, but a good copy. FIRST AND ONLY EDITION of this guide of ancient Rome, mainly based on Iustus Lispius. The book was edited by Giovanni Angelo Ruffinelli and by him dedicated to Agostino Pallavicino. Ruff- inelli, who commissioned his editions to the main Roman typographers of the time, used as device the Aldine anchor and dolphin without the motto (cf. Il libro italiano del Cinquec- ento: produzione e commercio. Catalogo della mostra Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Roma 20 ottobre - 16 dicembre 1989, Rome, 1989, p. 119). Giovanni Maria Bardi, Count of Vernio, here dis- guised under the name of ‘Incruscato’, as he was called in the Accademia della Crusca, was born into a noble and rich family. He undertook the military career, participating to the war of Siena (1553-54), the defense of Malta against the Turks (1565) and the expedition against the Turks in Hun- gary (1594). -

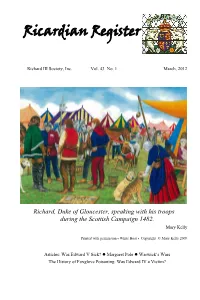

Ricardian Register

Ricardian Register Richard III Society, Inc. Vol. 43 No. 1 March, 2012 Richard, Duke of Gloucester, speaking with his troops during the Scottish Campaign 1482. Mary Kelly Printed with permission l White Boar l Copyright © Mary Kelly 2009 Articles: Was Edward V Sick? l Margaret Pole l Warwick’s Wars The History of Foxglove Poisoning: Was Edward IV a Victim? Inside cover (not printed) Contents Was Edward V Sick? 2 Margaret Pole 6 Warwick’s Wars 11 The history of foxglove poisoning, was Edward IV a victim? 17 Errata 21 Reviews 22 BOOK REVIEWS 22 DVD REVIEWS 27 From the Editor 30 Fiction 31 Sales Catalog–March, 2012 32 Board, Staff, and Chapter Contacts 37 Chapter Contacts 38 v v v ©2012 Richard III Society, Inc., American Branch. No part may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means mechanical, electrical or photocopying, recording or information storage retrieval—without written permission from the Society. Articles submitted by members remain the property of the author. The Ricardian Register is published four times per year. Subscriptions are available at $20.00 annually. In the belief that many features of the traditional accounts of the character and career of Richard III are neither supported by sufficient evidence nor reasonably tenable, the Society aims to promote in every possible way research into the life and times of Richard III, and to secure a re-assessment of the material relating to the period, and of the role in English history of this monarch. The Richard III Society is a nonprofit, educational corporation. -

Catalogue of Adoption Items Within Worcester Cathedral Adopt a Window

Catalogue of Adoption Items within Worcester Cathedral Adopt a Window The cloister Windows were created between 1916 and 1999 with various artists producing these wonderful pictures. The decision was made to commission a contemplated series of historical Windows, acting both as a history of the English Church and as personal memorials. By adopting your favourite character, event or landscape as shown in the stained glass, you are helping support Worcester Cathedral in keeping its fabric conserved and open for all to see. A £25 example Examples of the types of small decorative panel, there are 13 within each Window. A £50 example Lindisfarne The Armada A £100 example A £200 example St Wulfstan William Caxton Chaucer William Shakespeare Full Catalogue of Cloister Windows Name Location Price Code 13 small decorative pieces East Walk Window 1 £25 CW1 Angel violinist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW2 Angel organist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW3 Angel harpist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW4 Angel singing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW5 Benedictine monk writing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW6 Benedictine monk preaching East Walk Window 1 £50 CW7 Benedictine monk singing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW8 Benedictine monk East Walk Window 1 £50 CW9 stonemason Angel carrying dates 680-743- East Walk Window 1 £50 CW10 983 Angel carrying dates 1089- East Walk Window 1 £50 CW11 1218 Christ and the Blessed Virgin, East Walk Window 1 £100 CW12 to whom this Cathedral is dedicated St Peter, to whom the first East Walk Window 1 £100 CW13 Cathedral was dedicated St Oswald, bishop 961-992, -

A Transcription and Translation of Ms 469 (F.101R – 129R) of the Vadianische Sammlung of the Kantonsbibliothek of St. Gallen

A SCURRILOUS LETTER TO POPE PAUL III A Transcription and Translation of Ms 469 (f.101r – 129r) of the Vadianische Sammlung of the Kantonsbibliothek of St. Gallen by Paul Hanbridge PRÉCIS A Scurrilous Letter to Pope Paul III. A Transcription and Translation of Ms 469 (f.101r – 129r) of the Vadianische Sammlung of the Kantonsbibliothek of St. Gallen. This study introduces a transcription and English translation of a ‘Letter’ in VS 469. The document is titled: Epistola invectiva Bernhardj Occhinj in qua vita et res gestae Pauli tertij Pont. Max. describuntur . The study notes other versions of the letter located in Florence. It shows that one of these copied the VS469, and that the VS469 is the earliest of the four Mss and was made from an Italian exemplar. An apocryphal document, the ‘Letter’ has been studied briefly by Ochino scholars Karl Benrath and Bendetto Nicolini, though without reference to this particular Ms. The introduction considers alternative contemporary attributions to other authors, including a more proximate determination of the first publication date of the Letter. Mario da Mercato Saraceno, the first official Capuchin ‘chronicler,’ reported a letter Paul III received from Bernardino Ochino in September 1542. Cesare Cantù and the Capuchin historian Melchiorre da Pobladura (Raffaele Turrado Riesco) after him, and quite possibly the first generations of Capuchins, identified the1542 letter with the one in transcribed in these Mss. The author shows this identification to be untenable. The transcription of VS469 is followed by an annotated English translation. Variations between the Mss are footnoted in the translation. © Paul Hanbridge, 2010 A SCURRILOUS LETTER TO POPE PAUL III A Transcription and Translation of Ms 469 (f.101r – 129r) of the Vadianische Sammlung of the Kantonsbibliothek of St.