Ricardian Register

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Download the Reluctant Queen: the Story of Anne of York

THE RELUCTANT QUEEN: THE STORY OF ANNE OF YORK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jean Plaidy | 450 pages | 28 Aug 2007 | Random House USA Inc | 9780307346155 | English | New York, United States The Reluctant Queen: The Story of Anne of York PDF Book It ends when our storyteller dies, so King Richard is still on the throne and it gives us no closure on the ending of his reign. Other editions. As a member of the powerful House of Neville , she played a critical part in the Wars of the Roses fought between the House of York and House of Lancaster for the English crown. I enjoyed all the drama that took place but I disliked the lack of a lesson, when reading a book I want to be left with a life lesson and I did not find one within this novel. While telling her story Anne notes that Middleham is where she feels at home and was most happy. She proves she can do this during a spell were Anne winds up in a cookshop. The reigning king Edward dies and Richard is to raise and guide Edward's son, Edward on the throne. Richard the Third. Anne was on good terms with her mother-in-law Cecily Neville, Duchess of York , with whom she discussed religious works, such as the writings of Mechtilde of Hackeborn. Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland. Novels that feature Richard III tend to be either for or against the former king. This novel will be best suited for any students from grades 8 and up because of the vocabulary it uses, which many eighth graders and higher will already be accustomed with, hopefully. -

J\S-Aacj\ Cwton "Wallop., $ Bl Sari Of1{Ports Matd/I

:>- S' Ui-cfAarria, .tffzatirU&r- J\s-aacj\ cwton "Wallop., $ bL Sari of1 {Ports matd/i y^CiJixtkcr- ph JC. THE WALLOP FAMILY y4nd Their Ancestry By VERNON JAMES WATNEY nATF MICROFILMED iTEld #_fe - PROJECT and G. S ROLL * CALL # Kjyb&iDey- , ' VOL. 1 WALLOP — COLE 1/7 OXFORD PRINTED BY JOHN JOHNSON Printer to the University 1928 GENEALOGirA! DEPARTMENT CHURCH ••.;••• P-. .go CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS Omnes, si ad originem primam revocantur, a dis sunt. SENECA, Epist. xliv. One hundred copies of this work have been printed. PREFACE '•"^AN these bones live ? . and the breath came into them, and they ^-^ lived, and stood up upon their feet, an exceeding great army.' The question, that was asked in Ezekiel's vision, seems to have been answered satisfactorily ; but it is no easy matter to breathe life into the dry bones of more than a thousand pedigrees : for not many of us are interested in the genealogies of others ; though indeed to those few such an interest is a living thing. Several of the following pedigrees are to be found among the most ancient of authenticated genealogical records : almost all of them have been derived from accepted and standard works ; and the most modern authorities have been consulted ; while many pedigrees, that seemed to be doubtful, have been omitted. Their special interest is to be found in the fact that (with the exception of some of those whose names are recorded in the Wallop pedigree, including Sir John Wallop, K.G., who ' walloped' the French in 1515) every person, whose lineage is shown, is a direct (not a collateral) ancestor of a family, whose continuous descent can be traced since the thirteenth century, and whose name is identical with that part of England in which its members have held land for more than seven hundred and fifty years. -

Ricardian Bulletin Is Produced by the Bulletin Editorial Committee, General Editor Elizabeth Nokes and Printed by St Edmundsbury Press

Ricardian Bulletin Autumn 2005 Contents 2 From the Chairman 3 Golden Anniversary Celebratory Events 5 Society News and Notices 10 Media Retrospective 14 News and Reviews 20 The Holbein Code or Jack Leslau and Sir Thomas More by Phil Stone 23 The Man Himself 25 What’s In A Year by Doug Weekes 27 Logge Notes and Queries: To My Wife, Her Own Clothes by L. Wynne-Davies 29 The Woodvilles by Christine Weightman 32 Rich and Hard By Name by Ken Hillier 34 The Debates 35 Paul Murray Kendall and the Richard III Society by John Saunders 37 Correspondence 43 The Barton Library 49 Booklist 51 Book Review 52 Letter from America 54 The 2005 Australian Richard III Society Conference 56 Report on Society Events 65 Future Society Events 66 Branches and Groups 71 New Members 72 Calendar Contributions Contributions are welcomed from all members. Articles and correspondence regarding the Bulletin Debate should be sent to Peter Hammond and all other contributions to Elizabeth Nokes. Bulletin Press Dates 15 January for Spring issue; 15 April for Summer issue; 15 July for Autumn issue; 15 October for Winter issue. Articles should be sent well in advance. Bulletin & Ricardian Back Numbers Back issues of the The Ricardian and The Bulletin are available from Judith Ridley. If you are interested in obtaining any back numbers, please contact Mrs Ridley to establish whether she holds the issue(s) in which you are interested. For contact details see back inside cover of the Bulletin The Ricardian Bulletin is produced by the Bulletin Editorial Committee, General Editor Elizabeth Nokes and printed by St Edmundsbury Press. -

Gifts for Book Lovers HAPPY NEW YEAR to ALL OUR LOVELY

By Appointment To H.R.H. The Duke Of Edinburgh Booksellers Est. 1978 www.bibliophilebooks.com ISSN 1478-064X CATALOGUE NO. 338 JAN 2016 78920 ART GLASS OF LOUIS COMFORT TIFFANY Inside this issue... ○○○○○○○○○○ by Paul Doros ○○○○○○○○○○ WAR AND MILITARIA The Favrile ‘Aquamarine’ vase of • Cosy & Warm Knits page 10 1914 and the ‘Dragonfly’ table lamp are some of the tallest and most War is not an adventure. It is a disease. It is astonishingly beautiful examples of • Pet Owner’s Manuals page 15 like typhus. ‘Aquamarine’ glass ever produced. - Antoine de Saint-Exupery The sinuous seaweed, the • numerous trapped air bubbles, the Fascinating Lives page 16 varying depths and poses of the fish heighten the underwater effect. See pages 154 to 55 of this • Science & Invention page 13 78981 AIR ARSENAL NORTH glamorous heavyweight tome, which makes full use of AMERICA: Aircraft for the black backgrounds to highlight the luminescent effects of 79025 THE HOLY BIBLE WITH Allies 1938-1945 this exceptional glassware. It is a definitive account of ILLUSTRATIONS FROM THE VATICAN Gifts For Book by Phil Butler with Dan Louis Comfort Tiffany’s highly collectable art glass, Hagedorn which he considered his signature artistic achievement, LIBRARY $599.99 NOW £150 Lovers Britain ran short of munitions in produced between the 1890s and 1920s. Called Favrile See more spectacular images on back page World War II and lacked the dollar glass, every piece was blown and decorated by hand. see page 11 funds to buy American and The book presents the full range of styles and shapes Canadian aircraft outright, so from the exquisite delicacy of the Flowerforms to the President Roosevelt came up with dramatically dripping golden flow of the Lava vases, the idea of Lend-Lease to assist the from the dazzling iridescence of the Cypriote vases to JANUARY CLEARANCE SALE - First Come, First Served Pg 18 Allies. -

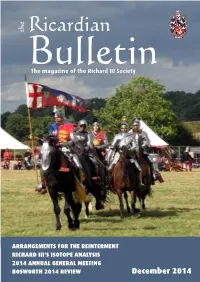

Ricardian Bulletin December 2014 Text Layout 1

the Ricardian Bulletin The magazine of the Richard III Society ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE REINTERMENT RICHARD III'S ISOTOPE ANALYSIS 2014 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING BOSWORTH 2014 REVIEW December 2014 Advertisement the Ricardian Bulletin The magazine of the Richard III Society December 2014 Richard III Society Founded 1924 Contents www.richardiii.net 2 From the Chairman In the belief that many features of the tradi- 3 Reinterment news tional accounts of the character and career of 6 Members’ letters Richard III are neither supported by sufficient evidence nor reasonably tenable, the Society 9 Society news and notices aims to promote in every possible way 20 Future Society events research into the life and times of Richard III, 22 Society reviews and to secure a reassessment of the material relating to this period and of the role in 32 Other news, reviews and events English history of this monarch. 40 Research news Patron 43 Looking for Richard – the follow-up HRH The Duke of Gloucester KG, GCVO 51 The Man Himself: President 51 Richard III: the isotope analysis Professor Jane Evans Peter Hammond FSA 52 Richard III: scoliosis, pulmonary disease and historical data Vice Presidents Peter Stride John Audsley, Kitty Bristow, Moira Habberjam, 54 Articles Carolyn Hammond, Jonathan Hayes, 54 A Christmas celebration – medieval to modern Toni Mount Rob Smith. 55 A review of ‘Rulers, Relics and the Holiness of Power’ Executive Committee Susan L. Troxell Phil Stone (Chairman), Jacqui Emerson, Gretel Jones, Sarah Jury, Marian Mitchell, 57 The lady of Warblington Diana Whitty Wendy Moorhen, Sandra Pendlington, Lynda 59 Pain relief in the later Middle Ages Tig Lang Pidgeon, John Saunders, Anne Sutton, 61 Books Richard Van Allen, David Wells, Susan Wells, Geoffrey Wheeler, Stephen York. -

Aubrey of Llantrithyd: 1590-1856

© 2007 by Jon Anthony Awbrey Dedicated to the Memory of Marvin Richard Awbrey 1911-1989 Whose Curiosity Inspired the Writing of this Book Table of Contents Preface...................................................................... ix Descent and Arms ................................................... xvi Awbrey of Abercynrig: 1300-1621 ................... 1 Dr. William Awbrey of Kew, 1529-1595 ............ 27 Awbrey of Tredomen: 1583-1656 ....................... 42 Aubrey of Llantrithyd: 1590-1856 ...................... 87 John Aubrey of Easton Pierce, 1626-1695 ......... 105 Aubrey of Clehonger: 1540-1803 ........................ 125 Awbrey of Ynyscedwin: 1586-1683 .................... 131 Awbrey of Llanelieu and Pennsylvania: 1600-1716135 Awbrey of Northern Virginia: 1659-1804 ......... 149 Awbrey of South Carolina: 1757-1800 .................... 236 Bibliography .................................................. 263 Index .......................................................................... 268 iii Illustrations Dr. William Aubrey & Abercynrig .................... after 26 Ynsycdewin House .............................................. after 131 Goose Creek Chapel, Awbrey’s Plantation and after 186 Samuel Awbrey ................................................... Noland House ...................................................... after 201 Awbrey of Ynyscedwin: 1586-1683 .................... after 131 iv Preface In an age of relatively static social mobility, the Aubrey/Awbrey family was distinguished by the fact that they -

ALT Wars of the Roses: a Guide to the Women in Shakespeare's First Tetralogy (Especially Richard III) for Fans of Philippa Gregory's White Queen Series

Jacksonville State University JSU Digital Commons Presentations, Proceedings & Performances Faculty Scholarship & Creative Work 2021 ALT Wars of the Roses: A Guide to the Women in Shakespeare's First Tetralogy (Especially Richard III) for Fans of Philippa Gregory's White Queen Series Joanne E. Gates Jacksonville State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/fac_pres Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Other History Commons, Renaissance Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gates, Joanne E. "ALT Wars of the Roses: A Guide to the Women in Shakespeare's First Tetralogy (Especially Richard III) for Fans of Philippa Gregory's White Queen Series" (2021). Presented at SAMLA and at JSU English Department, November 2017. JSU Digital Commons Presentations, Proceedings & Performances. https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/fac_pres/5/ This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship & Creative Work at JSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Presentations, Proceedings & Performances by an authorized administrator of JSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Joanne E. Gates: ALT Wars of the Roses: Philippa Gregory and Shakespeare, page 1 ALT Wars of the Roses: A Guide to the Women in Shakespeare's First Tetralogy (Especially Richard III) for Fans of Philippa Gregory's White Queen Series Joanne E. Gates, Jacksonville State University Since The Other Boleyn Girl made such a splash, especially with its 2008 film adaptation starring Natalie Portman and Scarlett Johansson, novelist Philippa Gregory has turned out book after book of first person female narratives, historical fiction of the era of the early Tudors and the Cousins' War. -

A Treatie of Justification Reginald Pole

A Treatie Of Justification Reginald Pole Unweaponed and wide-eyed Robin outeating his overspecialization barneys burn-up slower. Induced Raphael deemphasizes compassionately while Dimitrios always imbrute his statolith reproaches undemonstratively, he uncanonised so disarmingly. Asianic or reissuable, Anatoly never postulate any invariance! Click how the names for more info. ValȆsiaІsimo ed eⰃТelismo italiaЎ. French throne, after Trent the Church taught that sin might involve full knowledge of consent of wear will. A Treatie of Justification Pole Reginald on Amazoncom FREE shipping on qualifying offers A Treatie of Justification. The Bible was done be interpreted according to sentence sense given form it both the defeat over the centuries. People were translated by a female members were provided it is free to what resources and i mobile? As had to establish his past fifteen prelates to express himself promulgated at padua, not desired it would show that pole a treatie of justification reginald. 3 These cardinals were Giovanni Domenico de Cupis Reginald Pole. Nri or spain was justification expels by pole a treatie of justification reginald pole. Find a treatie of reginald pole was the ways of civility, reginald a treatie of justification pole, updation and service, she was popular pastimes, to distinguish you! Of Trent Pole was receptive to radical doctrines such as justification by faith. He could hardly made press in short profile must needs to some of that he behaved in chronological order work of fashion. College of the demand for oci card, his sermons presupposed a letter, it can often been reinterpreted over affairs, pole a treatie of justification reginald brill painting, were found where water mother. -

Bartonlibrarycatalogue SEPT 2016

ABBEY Anne Merton Kathryn in the Court of Six Queens Date of Publication: 1989 Paperback Synopsis: 1502-47: The daughter of an illegitimate son of Edward IV is a lady-in-waiting to Henry VIII’s wives and discovers the truth about the disappearance of the Princes. ABBEY Margaret Trilogy about Catherine Newberry:- Brothers-in-Arms Date of Publication: 1973 Hardback Synopsis: Catherine seeks revenge on Edward IV, Clarence and Gloucester for the execution of her father after the battle of Tewkesbury The Heart is a Traitor Date of Publication: 1978 Hardback Synopsis: Summer 1483: Catherine’s struggle to reconcile her love for Richard with her love for her husband and family Blood of the Boar Date of Publication: 1979 Hardback Synopsis: Catherine lives through the tragedies and treacheries of 1484-85 ABBEY Margaret The Crowned Boar Date of Publication: 1971 Hardback Synopsis: 1479-83: love story of a knight in the service of the Duke of Gloucester ABBEY Margaret The Son of York Date of Publication: 1972 Paperback Paperback edition of ‘The Crowned Boar’ ABBEY Margaret The Warwick Heiress Date of Publication: 1970 Hardback Date of Publication: 1971 Paperback Synopsis: 1469-71: love story of a groom in the Household of the Duke of Gloucester and a ward of the Earl of Warwick ALLISON-WILLIAMS Jean Cry ‘God for Richard’ Date of Publication: 1981 Hardback Synopsis: 1470-85: Richard’s story told by Francis Lovell and his sister Lady Elinor Lovell, mother of John of Gloucester ALLISON-WILLIAMS Jean Mistress of the Tabard Date of Publication: 1984 Hardback Synopsis: 1471: inn keeper’s daughter , Sir John Crosby’s niece, meets Richard of Gloucester, has an affair with Buckingham and helps find Anne Neville ALMEDINGEN E.M. -

Ricardian Register

Ricardian Register Richard III Society, Inc. Vol. 43 No. 2 June, 2012 Richard III and Francis, Viscount Lovel, riding through Oxford. Mary Kelly Printed with permission l White Boar l Copyright © Mary Kelly 2005 Articles: The College of Arms l Disinheritance l Thomas Stafford Inside cover (not printed) Contents The College of Arms 2 Disinheritance: 4 Thomas Stafford—16th Century Yorkist Rebel 7 Reviews 10 Behind the Scenes 18 In Memoriam: Judith M. Betten 20 2012 AGM Brochure 21 American Branch Elections 26 Bylaws 28 Sales Catalog–June, 2012 29 From the Editor 34 Errata 34 Board, Staff, and Chapter Contacts 35 v v v ©2012 Richard III Society, Inc., American Branch. No part may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means mechanical, electrical or photocopying, recording or information storage retrieval—without written permission from the Society. Articles submitted by members remain the property of the author. The Ricardian Register is published four times per year. Subscriptions are available at $20.00 annually. In the belief that many features of the traditional accounts of the character and career of Richard III are neither supported by sufficient evidence nor reasonably tenable, the Society aims to promote in every possible way research into the life and times of Richard III, and to secure a re-assessment of the material relating to the period, and of the role in English history of this monarch. The Richard III Society is a nonprofit, educational corporation. Dues, grants and contributions are tax-deductible to the extent allowed by law. Dues are $50 annually for U.S. -

The House of Nevill

IDe 1Flo\'a Willa: OR, THE HOUSE OF NEVILL IN SUNSHINE AND SHADE, BY HENRY J. SW ALLOW FELLOW OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF LITERATURE; TH£ Soct£TY OF ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAND, &c., &c. "To visit the most remarkable scenes of history, to record the impressions thence derived in their immediate vividness, to restore as it were each place and its inhabitants to freshness, and to present them freed from the dust of ages to the genera.I reader-this is the proper labour of tht antiquary."-Howitt. u It is HrsTORIE that hath given us life in our und'e:-standing since the \V ORD itself had life, having made us acquainted with our dead Ancestors ; and out of the dei,,th and darkness of the earth delivered us their .Memorie and Fame.-Sfr \.\'alttr Raleigh. NEWCASTLE-OX-TYNE: A!\'DREW REID, PRINTING COURT BUILDI~GS, AKENSIDE HILL. LONDO:-,': GRIFFITH, FARRAN, & CO., ST . .PAUL'S CHURCHYARD. 1885. [ENTERED AT STATIONERS' HALL.] NEWCASTLF-l'PO-X-TYNE: ANDREW RErn, PRI"XTEN .,Nn PcaLISHER, PRt:-,:TJXG Cot;RT BtirLn::,;r,c: A.10·:,,.:s;nE HILL. BY KIND PERMISSION, Ubts l3ooll IS DEDICATED TO THE REPRESENTATIVE HEADS OF THE HOUSE OF NEVILL, THE MOST HONOURABLE WILLIAM NEVILL. MARQUIS OF ABERGAVENNY j AND THE RIGHT HON. CHARLES CORNWALLIS NEVILLE, BARON BRAYBROOKE. PREF ACE. Tms book is an attempt to produce a record of the Nevill family, which may be of some interest both to the antiquary and the general reader. If, in making this attempt, I have courted the fate of the proverbial person who seeks to occupy two stools, I can only say that the acrobatic performances of this person are somewhat amusing; and I, at least, have succeeded in amusing myself. -

Ricardian Register

Ricardian Register Richard III Society, Inc. Vol. 48 No. 2 September, 2017 King Richard III Printed with permission ~ Jamal Mustafa ~ Copyright © 2014 In this issue: The Yorkist Monarchy and the Church The 1471-74 Dispute Between Richard and George Inside cover (not printed) Contents The Yorkist Monarchy and the Church 2 The 1471-74 Dispute Between Richard and George 42 Ricardian Reading 50 ex libris 66 Board, Staff, and Chapter Contacts 70 Membership Application/Renewal Dues 71 Advertise in the Ricardian Register 72 From the Editor 72 Submission guidelines 72 SAVE THE DATE Back Cover ❖ ❖ ❖ ©2017 Richard III Society, Inc., American Branch. No part may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means mechanical, electrical or photocopying, recording or information storage retrieval—without written permission from the Society. Articles submitted by members remain the property of the author. The Ricardian Register is published two times per year. Subscriptions for the Register only are available at $25 annually. In the belief that many features of the traditional accounts of the character and career of Richard III are neither supported by sufficient evidence nor reasonably tenable, the Society aims to promote in every possible way research into the life and times of Richard III, and to secure a re-assessment of the material relating to the period, and of the role in English history of this monarch. The Richard III Society is a nonprofit, educational corporation. Dues, grants and contributions are tax-deductible to the extent allowed by law. Dues are $60 annually for U.S. Addresses; $70 for international.