Cardinal Cajetan Renaissance Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beware of False Shepherds, Warhs Hem. Cardinal

Member of Audit Bureau of Circulations Principals in Pallium Ceremony i * BEWARE OF FALSE SHEPHERDS, % WARHS HEM. CARDINAL STRITCH Contonto Copjrrighted by the Catholic Preas Society, Inc. 1946— Pemiosion to reproduce, Except on Articles Otherwise Marke^ given After 12 M. Friday Following Issue Traces Catastrophes DENVER OONOLIC Of Modern Society To Godless Leaders I ^ G I S T E R Sermon al Pallium Ceremony in Denver Cathe The National Catholic Welfare Conference News Service Supplies The Denver Catholic Register. We dral Shows How Archbishop Shares in Have Also the International Nows Service (Wire and Mail), a Large Special Service, Seven Smaller Services, Photo Features, and Wide World Photos. (3 cents per copy) True Pastoral Office VOL. XU. No. 35. DENVER, COLO., THURSDAY, A PR IL 25, 1946. $1 PER YEAR Beware of false shepherds who scoff at God, call morality a mere human convention, and use tyranny and persecution as their staff. There is more than a mere state ment of truth in the words of Christ: “I am the Good Shep Official Translation of Bulls herd.” There is a challenge. Other shepherds offer to lead men through life but lead men astray. Christ is the only shepherd. Faithfully He leads men to God. This striking comparison of shepherds is the theme Erecting Archdiocese Is Given of the sermon by H. Em. Cardinal Samuel A. Stritch of Chicago in the Solemn Pon + ' + + tifical Mass in the Deliver Ca An official translation of the PERPETUAL MEMORY OF THE rate, first of all, the Diocese of thedral this Thursday morning, Papal Bulls setting up the Arch EVENT Denver, together with its clergy April 25, at which the sacred pal diocese of Denver in 1941 was The things that seem to be more and people, from the Province of lium is being conferred upon Arch Bishop Lauds released this week by the Most helpful in procuring the greater Santa Fe. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1984

Vol. Ul No. 38 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 16,1984 25 cents House committee sets hearings for Faithful mourn Patriarch Josyf famine study bill WASHINGTON - The House Sub committee on International Operations has set October 3 as the date for hearings on H.R. 4459, the bill that would establish a congressional com mission to investigate the Great Famine in Ukraine (1932-33), reported the Newark-based Americans for Human Rights in Ukraine. The hearings will be held at 2 p.m. in Room 2200 in the Sam Rayburn House Office Building. The chairman of the subcommittee, which is part of the Foreign Affairs Committee, is Rep. Dan Mica (D-Fla.). The bill, which calls for the formation of a 21-member investigative commission to study the famine, which killed an esUmated ^7.^ million UkrdtftUllk. yif ітіІДЯДІШ'' House last year by Rep. James Florio (D-N.J.). The Senate version of the measure, S. 2456, is currently in the Foreign Rela tions Committee, which held hearings on the bill on August I. The committee is expected to rule on the measure this month. In the House. H.R. 4459 has been in the Subcommittee on International Operations and the Subcommittee on Europe and the Middle East since last November. According to AHRU, which has lobbied extensively on behalf of the legislation, since one subcommittee has Marta Kolomaysls scheduled hearings, the other, as has St. George Ukrainian Catholic Church in New Yoric City and parish priests the Revs, Leo Goldade and Taras become custom, will most likely waive was but one of the many Ulcrainian Catholic churches Prokopiw served a panakhyda after a liturgy at St. -

The Hospital and Church of the Schiavoni / Illyrian Confraternity in Early Modern Rome

The Hospital and Church of the Schiavoni / Illyrian Confraternity in Early Modern Rome Jasenka Gudelj* Summary: Slavic people from South-Eastern Europe immigrated to Italy throughout the Early Modern period and organized them- selves into confraternities based on common origin and language. This article analyses the role of the images and architecture of the “national” church and hospital of the Schiavoni or Illyrian com- munity in Rome in the fashioning and management of their con- fraternity, which played a pivotal role in the self-definition of the Schiavoni in Italy and also served as an expression of papal for- eign policy in the Balkans. Schiavoni / Illyrians in Early Modern Italy and their confraternities People from the area broadly coinciding with present-day Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Herzegovina, and coastal Montenegro, sharing a com- mon Slavonic language and the Catholic faith, migrated in a steady flux to Italy throughout the Early Modern period.1 The reasons behind the move varied, spanning from often-quoted Ottoman conquests in the Balkans or plague epidemics and famines to the formation of merchant and diplo- matic networks, as well as ecclesiastic or other professional career moves.2 Moreover, a common form of short-term travel to Italy on the part of so- called Schiavoni or Illyrians was the pilgrimage to Loreto or Rome, while the universities of Padua and Bologna, as well as monastery schools, at- tracted Schiavoni / Illyrian students of different social extractions. The first known organized groups described as Schiavoni are mentioned in Italy from the fifteenth century. Through the Early Modern period, Schiavoni / Illyrian confraternities existed in Rome, Venice, throughout the Marche region (Ancona, Ascoli, Recanati, Camerano, Loreto) and in Udine. -

Patronage and Dynasty

PATRONAGE AND DYNASTY Habent sua fata libelli SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES SERIES General Editor MICHAEL WOLFE Pennsylvania State University–Altoona EDITORIAL BOARD OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES ELAINE BEILIN HELEN NADER Framingham State College University of Arizona MIRIAM U. CHRISMAN CHARLES G. NAUERT University of Massachusetts, Emerita University of Missouri, Emeritus BARBARA B. DIEFENDORF MAX REINHART Boston University University of Georgia PAULA FINDLEN SHERYL E. REISS Stanford University Cornell University SCOTT H. HENDRIX ROBERT V. SCHNUCKER Princeton Theological Seminary Truman State University, Emeritus JANE CAMPBELL HUTCHISON NICHOLAS TERPSTRA University of Wisconsin–Madison University of Toronto ROBERT M. KINGDON MARGO TODD University of Wisconsin, Emeritus University of Pennsylvania MARY B. MCKINLEY MERRY WIESNER-HANKS University of Virginia University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee Copyright 2007 by Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri All rights reserved. Published 2007. Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies Series, volume 77 tsup.truman.edu Cover illustration: Melozzo da Forlì, The Founding of the Vatican Library: Sixtus IV and Members of His Family with Bartolomeo Platina, 1477–78. Formerly in the Vatican Library, now Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana. Photo courtesy of the Pinacoteca Vaticana. Cover and title page design: Shaun Hoffeditz Type: Perpetua, Adobe Systems Inc, The Monotype Corp. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Dexter, Michigan USA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Patronage and dynasty : the rise of the della Rovere in Renaissance Italy / edited by Ian F. Verstegen. p. cm. — (Sixteenth century essays & studies ; v. 77) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-931112-60-4 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-931112-60-6 (alk. paper) 1. -

Most Rev. Emmanuel Suarez, OP Eightieth Master General

DOMINICAN A Vol. XXXI DECEMBER, 1946 No.4 MOST REV. EMMANUEL SUAREZ, O.P. EIGHTIETH MASTER GENERAL NCE more a son of the Province of Spain has been chosen to lead the Friars Preachers. Ninety-two electors representing the 8,000 members of the Order throughout the world met Il at the Angelicum Pontifical University on September 21, and chose the Most Rev. Emmanuel Suarez, O.P., rector of the Angeli cum, as the Master General. Father Suarez is the eightieth Master General elected since Pope Honorius III approved the foundation of the Order in 1216. He suc ceeds Father Martin Stanislaus Gillet, who has been named Titular Archbishop of Nicea, by His Holiness Pope Pius XII. Father Gillet was elected seventeen years ago and held the office five years beyond the statutory twelve years because the war prevented a convocation of the General Chapter at the appointed time. The new Master General was born in Campomanes, Austurias, on November 5, 1895. Upon the completion of his early classical studies at Coriax in the province of Oviedo, he received the Dominican habit on August 28, 1913, and made his profession on August 30, 1914. He continued his studies in philosophy and theology at the University of Salamanca, where he earned degress with high honors. Following his Ordination at Salamanca, he was sent to the University of Madrid, to study Civil Law and was awarded his doctorate with highest honors. Shortly thereafter, Fr. Suarez :went to Rome for further studies at the Collegio Angelico. He took the course at the Roman Rota, for which he wrote his brilliant and widely known examination thesis, De Remotione Parochorum. -

Analysis of Constitution

ANALYSIS OF CONSTITUTION ARTICLE I Section 1 Name of Order Section 2 Name of Convent General Section 3. Name of Priory; of Knight ARTICLE II Section 1 Jurisdiction ARTICLE III Section 1 Membership Section 2 Representative must be member ARTICLE IV Section 1 Names and rank of officers ARTICLE V Section 1 Who eligible to office Section 2 Member or officer must be in good standing in Priory Section 3. Only one officer from a Priory Section 4 Officers selected at Annual Conclave Section 5 Officers must be installed Section 6 Officers must make declaration Section 7 Officers hold office until successors installed Section 8 Vacancies, how filled ARTICLE VI Section 1 Annual and special Conclaves Section 2 Quorum ARTICLE VII Section 1 Convent General has sole government of Priories Section 2 Powers to grant dispensation, and warrants, to revoke warrants Section 3. Power to prescribe ceremonies of Order Section 4 Power to require fees and dues Section 5 Disciplinary, for violation of laws ARTICLE VIII Section 1 Who shall preside at Convent General Section 2 Powers and duties of Grand Master-General Section 3. Convent General may constitute additional offices ARTICLE IX Section 1 Legislation, of what it consists Section 2 How Constitution may be altered Section 3. When Constitution in effect 4 CONSTITUTION ARTICLE I - Names Section 1 This Order shall be known as the Knights of the York Cross of Honour and designated by the initials “K.Y.C.H.” Section 2 The governing body shall be known as Convent General, Knights of the York Cross of Honour. -

The Life of Philip Thomas Howard, OP, Cardinal of Norfolk

lllifa Ex Lrauis 3liiralw* (furnlu* (JlnrWrrp THE LIFE OF PHILIP THOMAS HOWARD, O.P., CARDINAL OF NORFOLK. [The Copyright is reserved.] HMif -ft/ tutorvmjuiei. ifway ROMA Pa && Urtts.etOrl,,* awarzK ^n/^^-hi fofmmatafttrpureisJPTUS oJeffe Chori quo lufas mane<tt Ifouigionis THE LIFE OP PHILIP THOMAS HOWAKD, O.P. CARDINAL OF NORFOLK, GRAND ALMONER TO CATHERINE OF BRAGANZA QUEEN-CONSORT OF KING CHARLES II., AND RESTORER OF THE ENGLISH PROVINCE OF FRIAR-PREACHERS OR DOMINICANS. COMPILED FROM ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPTS. WITH A SKETCH OF THE EISE, MISSIONS, AND INFLUENCE OF THE DOMINICAN OEDEE, AND OF ITS EARLY HISTORY IN ENGLAND, BY FE. C. F, EAYMUND PALMEE, O.P. LONDON: THOMAS KICHAKDSON AND SON; DUBLIN ; AND DERBY. MDCCCLXVII. TO HENRY, DUKE OF NORFOLK, THIS LIFE OF PHILIP THOMAS HOWARD, O.P., CAEDINAL OF NOEFOLK, is AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED IN MEMORY OF THE FAITH AND VIRTUES OF HIS FATHEE, Dominican Priory, Woodchester, Gloucestershire. PREFACE. The following Life has been compiled mainly from original records and documents still preserved in the Archives of the English Province of Friar-Preachers. The work has at least this recommendation, that the matter is entirely new, as the MSS. from which it is taken have hitherto lain in complete obscurity. It is hoped that it will form an interesting addition to the Ecclesiastical History of Eng land. In the acknowledging of great assist ance from several friends, especial thanks are due to Philip H. Howard, Esq., of Corby Castle, who kindly supplied or directed atten tion to much valuable matter, and contributed a short but graphic sketch of the Life of the Cardinal of Norfolk taken by his father the late Henry Howard, Esq., from a MS. -

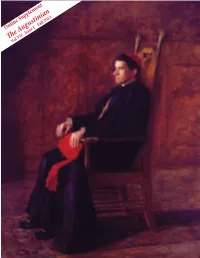

The Augustinian Vol VII

Online Supplement The Augustinian Vol VII . Issue I Fall 2012 Volume VII . Issue I The Augustinian Fall 2012 - Online Supplement Augustinian Cardinals Fr. Prospero Grech, O.S.A., was named by Pope Benedict XVI to the College of Cardinals on the Feast of the Epiphany, January 6, 2012. On February 18, 2012, when he received the red biretta, he joined the ranks of twelve other Augustinian Friars who have served as Cardinals. This line stretches back to 1378, when Bonaventura Badoardo da Padova, O.S.A., was named Cardinal, the first Augustinian Friar so honored. Starting with the current Cardinal, Prospero Grech, read a biographical sketch for each of the thirteen Augustinian Cardinals. Friars of the Province of Saint Thomas of Villanova Sebastiano Martinelli, O.S.A., the most recent Augustinian Cardinal prior to Cardinal Prospero Grech, O.S.A., served as Apostolic Delegate to the United States (1896 - 1902). While serving in this position, he made several trips to visit Augustinian sites. In 1897, while visiting Villanova, he was pho- tographed with the professed friars of the Province. Among these men were friars who served in leader- ship roles for the Province, at Villanova College, and in parishes and schools run by the Augustinians. Who were these friars and where did they serve? Read a sketch, taken from our online necrology, Historical information for Augustinian Cardinals for each of the 17 friars pictured with Archbishop supplied courtesy of Fr. Michael DiGregorio, O.S.A., Sebastiano Martinelli. Vicar General of the Order of St. Augustine. On the Cover: Thomas Eakins To read more about Archbishop Martinelli and Portrait of Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli, 1902 Cardinal Grech, see the Fall 2012 issue of The Oil on panel Augustinian magazine, by visiting: The Armand Hammer Collection http://www.augustinian.org/what-we-do/media- Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation room/publications/publications Hammer Museum, Los Angeles Photo by Robert Wedemeyer Copyright © 2012, Province of St. -

Origins and Development of Religious Orders

ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT OF RELIGIOUS ORDERS William A. Hinnebusch, O.P. The article is from a Journal: Review for Religious. It helps us to understand the CONTEXT of St Ignatius while founding the Society of Jesus. An attentive study of the origins and history of religious orders reveals that there are two primary currents in religious life--contemplative and apostolic. Vatican II gave clear expression to this fact when it called on the members of every community to "combine contemplation with apostolic love." It went on to say: "By the former they adhere to God in mind and heart; by the latter they strive to associate themselves with the work of redemption and to spread the Kingdom of God" (PC, 5). The orders founded before the 16th century, with the possible exception of the military orders, recognized clearly the contemplative element in their lives. Many of them, however, gave minimum recognition to the apostolic element, if we use the word "apostolic" in its present-day meaning, but not if we understand it as they did. In their thinking, the religious life was the Apostolic life. It reproduced and perpetuated the way of living learned by the Apostles from Christ and taught by them to the primitive Church of Jerusalem. Since it was lived by the "Twelve," the Apostolic life included preaching and the other works of the ministry. The passage describing the choice of the seven deacons in the Acts of the Apostles clearly delineates the double element in the Apostolic life and underlines the contemplative spirit of the Apostles. -

The History of the Augustinians As a Teaching Order in the Midwestern Province

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1965 The History of the Augustinians as a Teaching Order in the Midwestern Province Joseph Anthony Linehan Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Linehan, Joseph Anthony, "The History of the Augustinians as a Teaching Order in the Midwestern Province" (1965). Dissertations. 776. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/776 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 1965 Joseph Anthony Linehan THF' RISTORI OF Tl[F, AUOUSTINIANS AS A Tt'ACHINO ormm IN THE JlIDWlmERN PlOVIlCR A nt. ..ertat.1on Submi toted to the Facul\7 ot the Gra.da1&te School of ~1a Un! wnd.ty in Partial PUlt1l.l.aent ot the Requirements tor the Degree of Docrtor of Fdnoation I would 11ke to thank the Reverend Daniel lI&rt1gan, O.S.A., who christened. th1s etud7. Reverend lf10bael Ibgan, D.S.A., who put it on ita feet, Dr. Jobn V.roz!'l1a.k, who taught it to walk. and Dr. Paul t1nieJ7, wm guided 1t. ThanlaI to st. Joseph Oupert1no who nlWer fails. How can one adequate~ thank his parente tor their sacrlf'loee, their 10... and their guidanoe. Is thank JOt! suttlc1ent tor a nil! who encourages when night school beoomea intolerable' 1bw do ,ou repay two 11 ttle glrls liM mat not 'bo'ther daddy in h1s "Portent- 1"OGIIl? Tou CIDIOt appreoiate tbe exoeUent teachers who .Mope )'Our future until you a~ an adult. -

SOME IMPORTANT DATES 1170 Birth of Saint Dominic in Calaruega, Spain. 1203 Dominic Goes with His Bishop, Diego, on a Mission To

SOME IMPORTANT DATES 1170 Birth of Saint Dominic in Calaruega, Spain. 1203 Dominic goes with his bishop, Diego, on a mission to northern Europe. On the way he discovers, in southern France, people who no longer accept the Christian faith. 1206 Foundation of the first monastery of Dominican nuns in Prouille, France. 1215 Dominic and his first companions gather together in Toulouse. 1216 Pope Honorius III approves the foundation of the Dominican Order. 1217 Dominic disperses his friars to set up communities in Paris, Bologna, Rome and Madrid. 1221 8th August, Dominic dies in Bologna. 1285 Foundation of the Dominican Third Order. Its Rule approved by the Master General, Munoz de Zamora. 1347 Birth of Catherine of Siena, patroness of Lay Dominicans. 1380 29th April, Catherine of Siena dies in Rome. 1405 Pope Innocent VII approves Rule of the Third Order. 1898 Establishment of the Dominican Order in Australia. 1932 Second Rule of the Third Order approved by the Master General, Louis Theissling. 1950 Establishment of the Province of the Assumption. 1964 Third Rule approved. 1967 First National Convention of Dominican Laity in Australia (held in Canberra). 1969 Fourth Rule promulgated by the Master General, Aniceto Fernandez. 1972 Fourth Rule approved (on an experimental basis) by the Sacred Congregation for Religious). 1974 Abolition of terms "Third Order" and "Tertiaries". 1985 First International Lay Dominican Congress held in Montreal, Canada. 1987 Fifth (present) Rule approved by the Sacred Congregation for Religious and Secular Institutes and promulgated by the Master, Damien Byrne. The Dominican Laity Handbook (1994) P68 THE THIRD ORDER OF ST. -

January - March 2021

January - March 2021 JANUARY - MARCH 2010 Journal of Franciscan Culture Issued by the Franciscan Friars (OFM Malta) 135 Editorial EDITORIAL THE DEMOCRATIC DIMENSION OF AUTHORITY The Catholic Church is considered to be a kind of theocratic monarchy by the mass media. There is no such thing as a democratically elected government in the Church. On the universal level the Church is governed by the Pope. As a political figure the Pope is the head of state of the Vatican City, which functions as a mini-state with all the complexities of government Quarterly journal of and diplomatic bureaucracy, with the Secretariat of State, Franciscan culture published since April 1986. Congregations, Offices and the esteemed service of its diplomatic corps made up of Apostolic Nuncios in so many countries. On Layout: the local level the Church is governed by the Bishop and all the John Abela ofm Computer Setting: government structures of a Diocese. There is, of course, place for Raymond Camilleri ofm consultation and elections within the ecclesiastical structure, but the ultimate decisions rest with the men at the top. The same can Available at: be said of religious Orders, having their international, national http://www.i-tau.com and local organs of government. The Franciscan Order is also structured in this way, with the minister general, the ministers All original material is Copyright © TAU Franciscan provincial, custodes and local guardians and superiors. Communications 2021 Indeed, Saint Francis envisaged a kind of fraternity based on mutual co-responsibility. He did not accept the title of abbot or prior for the superiors of the Order, but wanted them to be “ministers and servants” of the brotherhood.