Hawaii's Coastal Nonpoint Pollution Control Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meroz-Plank Canoe-Edited1 Without Bold Ital

UC Berkeley Survey Reports, Survey of California and Other Indian Languages Title The Plank Canoe of Southern California: Not a Polynesian Import, but a Local Innovation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1977t6ww Author Meroz, Yoram Publication Date 2013 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Plank Canoe of Southern California: Not a Polynesian Import, but a Local Innovation YORAM MEROZ By nearly a millennium ago, Polynesians had settled most of the habitable islands of the eastern Pacific, as far east as Easter Island and as far north as Hawai‘i, after journeys of thousands of kilometers across open water. It is reasonable to ask whether Polynesian voyagers traveled thousands of kilometers more and reached the Americas. Despite much research and speculation over the past two centuries, evidence of contact between Polynesia and the Americas is scant. At present, it is generally accepted that Polynesians did reach South America, largely on the basis of the presence of the sweet potato, an American cultivar, in prehistoric East Polynesia. More such evidence would be significant and exciting; however, no other argument for such contact is currently free of uncertainty or controversy.1 In a separate debate, archaeologists and ethnologists have been disputing the rise of the unusually complex society of the Chumash of Southern California. Chumash social complexity was closely associated with the development of the plank-built canoe (Hudson et al. 1978), a unique technological and cultural complex, whose origins remain obscure (Gamble 2002). In a recent series of papers, Terry Jones and Kathryn Klar present what they claim is linguistic, archaeological, and ethnographical evidence for prehistoric contact from Polynesia to the Americas (Jones and Klar 2005, Klar and Jones 2005). -

Wao Kele O Puna Comprehensive Management Plan

Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan Prepared for: August, 2017 Prepared by: Nālehualawaku‘ulei Nālehualawaku‘ulei Nā-lehua-lawa-ku‘u-lei is a team of cultural resource specialists and planners that have taken on the responsibilities in preparing this comprehensive management for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Nā pua o kēia lei nani The flowers of this lovely lei Lehua a‘o Wao Kele The lehua blossoms of Wao Kele Lawa lua i kēia lei Bound tightly in this lei Ku‘u lei makamae My most treasured lei Lei hiwahiwa o Puna Beloved lei of Puna E mālama mākou iā ‘oe Let us serve you E hō mai ka ‘ike Grant us wisdom ‘O mākou nā pua For we represent the flowers O Nālehualawaku‘ulei Of Nālehualawaku‘ulei (Poem by na Auli‘i Mitchell, Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i) We come together like the flowers strung in a lei to complete the task put before us. To assist in the preservation of Hawaiian lands, the sacred lands of Wao Kele o Puna, therefore we are: The Flowers That Complete My Lei Preparation of the Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan In addition to the planning team (Nālehualawaku‘ulei), many minds and hands played important roles in the preparation of this Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan. Likewise, a number of support documents were used in the development of this plan (many are noted as Appendices). As part of the planning process, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs assembled the ‘Aha Kūkā (Advisory Council), bringing members of the diverse Puna community together to provide mana‘o (thoughts and opinions) to OHA regarding the development of this comprehensive management plan (CMP). -

The Canoe Is the People LEARNER's TEXT

The Canoe Is The People LEARNER’S TEXT United Nations Local and Indigenous Educational, Scientific and Knowledge Systems Cultural Organization Learnerstxtfinal_C5.indd 1 14/11/2013 11:28 The Canoe Is the People educational Resource Pack: Learner’s Text The Resource Pack also includes: Teacher’s Manual, CD–ROM and Poster. Produced by the Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (LINKS) Programme, UNESCO www.unesco.org/links Published in 2013 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France ©2013 UNESCO All rights reserved The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Coordinated by Douglas Nakashima, Head, LINKS Programme, UNESCO Author Gillian O’Connell Printed by UNESCO Printed in France Contact: Douglas Nakashima LINKS Programme UNESCO [email protected] 2 The Canoe Is the People: Indigenous Navigation in the Pacific Learnerstxtfinal_C5.indd 2 14/11/2013 11:28 contents learner’s SECTIONTEXT 3 The Canoe Is the People: Indigenous Navigation in the Pacific Learnerstxtfinal_C5.indd 3 14/11/2013 11:28 Acknowledgements The Canoe Is the People Resource Pack has benefited from the collaborative efforts of a large number of people and institutions who have each contributed to shaping the final product. -

U.S. Coast Guard at Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941

U.S. COAST GUARD UNITS IN HAWAII December 7, 1941 Coast Guard vessels in service in Hawaii were the 327-foot cutter Taney, the 190-foot buoy tender Kukui, two 125- foot patrol craft: Reliance and Tiger, two 78-foot patrol boats and several smaller craft. At the time of the attack, Taney was tied up at Pier Six in Honolulu Harbor, Reliance and the unarmed Kukui both lay at Pier Four and Tiger was on patrol along the western shore of Oahu. All were performing the normal duties for a peacetime Sunday. USCGC Taney (WPG-37); Commanding Officer: Commander Louis B. Olson, USCG. Taney was homeported in Honolulu; 327-foot Secretary Class cutter; Commissioned in 1936; Armament: two 5-inch/51; four 3-inch/ 50s and .50 caliber machine guns. The 327-foot cutter Taney began working out of Honolulu in as soon as she was commissioned. On the morning of 7 December 1941, she was tied up at pier six in Honolulu Harbor six miles away from the naval anchorage. After the first Japanese craft appeared over the island, Taney's crew went to general quarters and made preparations to get underway. While observing the attack over Pearl Harbor, Taney received no orders to move and did not participate in the initial attack by the Japanese. Just after 09:00, when the second wave of planes began their attack on the naval anchorage, Taney fired on high altitude enemy aircraft with her 3-inch guns and .50 caliber machine guns. The extreme range of the planes limited the effect of the fire and the guns were secured after twenty minutes. -

West Honolulu Watershed Study

West Honolulu Watershed Study Final Report Prepared For: Honolulu Board of Water Supply Department of Land and Natural Resources, Engineering Division U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Honolulu District Prepared By: Townscape, Inc. and Eugene P. Dashiell, AICP May 2003 West Honolulu Watershed Study - Final Report - Prepared for: HONOLULU BOARD OF WATER SUPPLY DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES ENGINEERING DIVISION U.S. ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS HONOLULU DISTRICT Prepared by: Townscape, Inc. and Eugene P. Dashiell, AICP May 2003 This page intentionally left blank. West Honolulu Watershed Study FINAL REPORT WEST HONOLULU WATERSHED STUDY ACKOWLEDGEMENTS This study was conducted under the direction of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Honolulu District (COE), through Section 22 of the Water Resources Development Act of 1974, as amended. Project manager for the West Honolulu Watershed Study was Derek Chow of COE, Engineer District, Honolulu. Local sponsorship for the study was provided jointly by the City and County of Honolulu Board of Water Supply, represented by Barry Usagawa, Principal Executive of the Water Resources Unit, and Scot Muraoka, Long-Range Planning Section; and the State of Hawaiÿi Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR), Engineering Division, which was represented by Sterling Yong, Head of the Flood Control and Dam Safety Section, and Eric Yuasa and Carty Chang of the Project Planning Section. The three co-sponsors of this study wish to acknowledge the following groups and individuals for their contribution to the West Honolulu Watershed Study: Principal Planner and President Bruce Tsuchida and Staff Planners Michael Donoho and Sherri Hiraoka of Townscape, Inc., contracted through the COE as the planning consultant for the study. -

Polynesian Origins and Migrations

46 POLYNESIAN CULTURE HISTORY From what continent they originally emigrated, and by what steps they have spread through so vast a space, those who are curious in disquisitions of this nature, may perhaps not find it very difficult to conjecture. It has been already observed, that they bear strong marks of affinity to some of the Indian tribes, that inhabit the Ladrones and Caroline Islands: and the same affinity may again be traced amongst the Battas and the Malays. When these events happened, is not so easy to ascertain; it was probably not very lately, as they are extremely populous, and have no tradition of their own origin, but what is perfectly fabulous; whilst, on the other hand, the unadulterated state of their general language, and the simplicity which still prevails in their customs and manners, seem to indicate, that it could not have been at any very distant period (Vol, 3, p. 125). Also considered in the journals is the possibility of multiple sources for the vast Polynesian culture complex, but the conclusion is offered that a common origin was more likely. The discussion of this point fore shadows later anthropological arguments of diffusion versus independent invention to account for similar culture traits: Possibly, however, the presumption, arising from this resemblance, that all these islands were peopled by the same nation, or tribe, may be resisted, under the plausible pretence, that customs very similar prevail amongst very distant people, without inferring any other common source, besides the general principles of human nature, the same in all ages, and every part of the globe. -

Tok Blong Evening Dec 16

Tok Blong Pasifik Pacific Peoples’ Partnership’s 40th Anniversary Special Edition Rising Tides: Our Lands, Our Waters, Our Peoples !1 Welcome to a special commemorative edition of our publication Tok Blong Pasifk, themed Rising Tides: Our Lands, Our Waters, Our Peoples. To celebrate Pacifc Peoples’ Partnership’s 40 years of action, we honour the resilience and depth of connections between Indigenous peoples and their environment as well as the tireless work of champions and change-makers, both north and south, who advocate for equity and sustainability that benefts us all … Papua Land of Peace - p.8 Pacifc Voices X-Change Artist for generations to come. Residency Programme - p.22 Rising Tides Opening Ceremony - p.12 Rising Tides Honouring Feast - p.13 One Wave Festival- p.14 Credit: Mark Gauti Credit: Mark Gauti We Are With You Vanuatu! Fundraising event in response to Cyclone Pam - p.10 Credit: Heather Tuft CONTENTS Pacific Peoples’ Partnership PPP Celebrates Five More Years of Pacifc Unity & Action….…………………. 4 Celebrating 40 Years of Action Talofa Lava from PPP’s President ..……………………….………………. 6 Established in 1975, Pacifc Peoples’ Partnership Executive Director’s Message …………………………………………….. 7 is a unique non-governmental , non-proft organization working with communities and West Papua: The Current Situation .………….……….………..…….…… 8 organizations in the South and North Pacifc to support shared aspirations for peace, cultural Vanuatu We are With You! …………………………………. ….…….….. 10 integrity, social justice, human dignity, and environmental sustainability by: Rising Tides: Our Lands, Our Waters, Our Peoples ………..…………….. 12 One Wave Festival ……………………………………………………….. 14 • Promoting increased understanding among Canadians on issues of importance to the 15 people of the Pacifc Islands. -

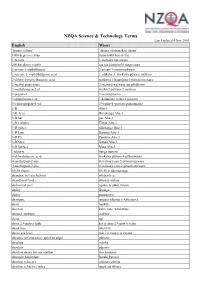

NZQA Science & Technology Terms

NZQA Science & Technology Terms Last Updated 4 Nov 2010 English Māori ‘fitness culture’ ‘ahurea whakapakari tinana’ 1000 degrees celsius mano takiri henekereti 1-hexene 1-waiwaro rua owaro 200 km above (earth) rua rau kiromita ki runga rawa 2-amino-3-methylbutane 2-amino-3-mewarop ūwaro 2–bromo–3–methylbutanoic acid 2–pūkeha–3–waikawa p ūwaro m ēwaro 2-chloro-3-methylbutanoic acid waikawa 2-haum āota-3-pūwaro mewaro 2-methyl propenoate 2-mewaro waiwaro rua p ōhākawa 2-methylpropan-2-ol waihä-2-pöwaro-2-mewaro 2-propanol 2-waih ā p ōwaro 3-chlorobutan-1-ol 3-haum āota waih ā-1-pūwaro 3–chloropropan–1–ol 3–waih ā–1–pōwaro p ūhaum āota 3-D Ahu-3 3-D Area Horahanga Ahu-3 3-D bar pae Ahu-3 3-D Column Tīwae Ahu-3 3-D effect rākeitanga Ahu-3 3-D Line Rārangi Ahu-3 3-D Pie Porohita Ahu-3 3-D Style Kāhua Ahu-3 3-D Surface Mata Ahu-3 3rd party hunga tuatoru 4-chlorobutanoic acid waikawa p ūwaro 4-pūhaum āota 4-methylpent-2-ene 4-waiwaro-rua-2-pēwaro mewaro 4-methylpent-2-yne 4-waiwaro-toru-2-pēwaro mewaro 50-50 chance 50-50 te t ūponotanga abandon, to leave behind whakar ērea abandoned (land) whenua mahue abdominal pain ngau o te puku, k ōpito ability āheinga ability pūmanawa aborigine tangata whenua o Ahitereiria abort haukoti abortion kuka, tahe, whakatahe abound, multiply makuru about mō about 2.4 metres high kei te āhua 2.4 mita te teitei about face tahuri k ē above sea level mai i te mata o te moana abrasive (of character), quick to anger pūtiotio absolute mārika absolute pūrawa absolute desire for one another tara koukoua Absolute Magnitude -

Bartram, P.K., J.J. Kaneko and G. Krasnick. 2006. Responsible

December 28, 2006 Prepared by: Paul Bartram J. John Kaneko MS, DVM George Krasnick PacMar, Inc. 3615 Harding Avenue, Suite 408-409 Honolulu, Hawaii 96816 Prepared for: Hawaii Seafood Project National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Department of Commerce This document was prepared by PacMar, Inc. under Award No. NA05NMF4521112 from NOAA, U.S. Department of Commerce. The statements, findings, conclusions and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOAA or the U.S. Department of Commerce. Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..............................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION TO PROJECT ...............................................................................................................2 SCORING RESPONSIBILITY OF HAWAII LONGLINE FISHERIES............................................7 IS “PRECAUTIONARY MANAGEMENT” BEING PROMOTED? .............................................. 11 REFERENCES............................................................................................................................................... 12 APPENDIX A ................................................................................................................................................ 14 ARTICLE 7 – FISHERIES MANAGEMENT ........................................................................................ 15 ARTICLE 8 – FISHING OPERATIONS................................................................................................ -

Cruise Terminal

Welcome Honolulu Harbor 2050 Master Plan Public Information Meeting August 4, 2021 1:00 p.m. to 4:30 p.m. ΖQůĞůŽƌŽĂĚĐĂƐƚ Department of Transportation Harbors Division Opening Remarks Derek Chow Deputy Director for Harbors 2 Department of Transportation, Harbors Division Honolulu Harbor 2050 Master Plan 3 3 2,600 TEU Vessel Carrying Capacity 1 5 1,500 150 2,600 TEU 8,000 Foot Trucks ŽĞŝŶŐϳϰϳ Container Double- ;ϭϲDŝůĞƐͿ Cargo Liners Ship Stack ;ϮϱĐƌĞƐͿ Trains ;ϳDŝůĞƐͿ ;ϭϯĐƌĞƐͿ 4 /ŶƚƌŽĚƵĐƚŝŽŶƐ ĞƉĂƌƚŵĞŶƚŽĨdƌĂŶƐƉŽƌƚĂƚŝŽŶĚŵŝŶŝƐƚƌĂƚŝŽŶ • Davis Yogi, Harbors Administrator • Neil Takekawa, Oahu District Manager • Peter Pillone, Oahu District, Commercial Harbor Manager Project Team: DOT-Harbors • Carter Luke, Engineering Program Manager • Arnold Liu, Planning Engineer • Celia Shen, Project Manager for Maritime • Mike Dichner, Statistician 5 /ŶƚƌŽĚƵĐƚŝŽŶƐ Project Team: R. M. Towill Corporation • David Tanoue, Project Principal • Jim Niermann, Project Manager for Maritime • Laura Mau, Project Manager for Non-Maritime • Michelle Marchant, Planner 6 /ŶƚƌŽĚƵĐƚŝŽŶƐ Project Team: Specialist Subconsultants • Linda Colburn, Where Talk Works • William Anonsen, The Maritime Group • Harold Westerman, Stantec Consulting, Ltd. • Roslin Arbuckle, Stantec Consulting, Ltd. • Faith Rex, SMS Research • Daniel Nahoopii, SMS Research • Jim Dannemiller, SMS Research • Kimi Yuen, PBR Hawai‘i • Jeff Seastrom, PBR Hawai‘i 7 /ŶƚƌŽĚƵĐƚŝŽŶƐ Project Team: Specialist Subconsultants • Ramsay Taum, PBR Hawai‘i • Hal Hammatt, Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i • Auli’i Mitchell, Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i • David Shideler, Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i • Tonia Moy, Fung and Associates • McKenna Makizuru, Fung and Associates • Alison Chiu, Fung and Associates • Randy Okaneku, The Traffic Management Consultant 8 Housekeeping • How to participate/comment • Slide reference # • Recording the meeting • End meeting by 4:30 p.m. -

Some Transportation and Communication Firsts in Hawaii

Some Transportation and Communication Firsts in Hawaii Robert C. Schmitt Few aspects of Hawaiian life and technology have changed as dramatically as transportation and communication. The past two centuries have produced many new and revolutionary developments—the steamship, railroad, street car, automobile, freeway, parking meter, balloon, airplane, postage stamp, newspaper, telephone, and radio, to name some of the most important or ubiquitous. Despite the significance of these innovations, in many cases little is known of their first appearance in the Islands. Standard historical works are often silent on the subject. For a surprisingly large number, conflicting claims (some clearly impossible) run through the literature. Sources are seldom mentioned. Wherever possible, these "firsts" are traced in the following pages. TRANSPORTATION Ocean travel. On January 20, 1778, at Waimea, Kauai, Hawaiians saw their first recorded foreign ships, the Resolution and Discovery, commanded by Cook and Clerke.1 The first vessel of foreign design to be built in the Islands was the 36-foot Britannia, designed and constructed by Vancouver's carpenters in February 1794 for Kamehameha's navy.2 The first whaleships to visit Hawaii were the Balena (or Balaena) out of New Bedford, commanded by Captain Edmund Gardner, and the 262-ton ship Equator from Newburyport, with Captain Elisha Folger as skipper. The two vessels arrived via California, anchoring in Kealakekua Bay on September 29, 1819.3 The first whaleship to enter Honolulu Harbor was the Maro, of Nantucket registry under Joseph Allen, master, in 1820.4 "The first wharf constructed at this port was at a point a little to the northward of the foot of Nuuanu Street," according to Thrum. -

THE STORY of PACIFIC SAILING CANOES and THEIR RIGS Adrian

From Buckfast to Borneo THE STORY OF PACIFIC SAILING CANOES AND THEIR RIGS Adrian Horridge ABSTRACT A revised survey of outrigger canoe rigs leads to the new conclusion that the primitive rig that made possible the Austronesian conquest of the Pacific was the mastless rig with a two-boom triangular sail supported on a loose prop, as survived in Madura and western Polynesia. It is proposed that the triangular sail spread across the Indian Ocean and became the lateen, which spread further to the Mediterranean and eventually to Portugal by the fourteenth century. New historical findings suggest that this Western lateen rig with a fixed mast, copied from a Portuguese caravellost in 1526, influeHced sailing practice in eastern Polynesia. Keywords: Pacific rigs, outrigger canoes, Austronesian, colonists. THE BEGINNING The first colonists from Indonesia certainly reached Australia more than fifty thousand years ago, but stone tools suitar 1 ~ to make dug-out canoes have not been found older than about twenty thousand years. Therefore the best guess is that the earliest sea crossings as far as the Solomon Islands were made with rafts.1 Of sailing rigs developed in those remote times we know nothing. However, a survey of the widespread sailing rafts still in use, mainly on rivers, in historic times, reveals a variety of rigs. The tak pai of Taiwan (Nishirnura 1925) had a square sail, the balsa rafts of the Peruvian coasts (Johnstone 1980: 224-28) used a two-boom triangular sail: the bamboo rafts (Ghe Be) of Haiphong Bay, Vietnam (Pietri 1949: 89) used a canvas lug sail or the low rounded junk sail of the southern Chinese: rafts in Fiji (Haddon and Hornell1936, i: 330) and Mangareva (Gambier Is.) (ibid: 91-94) had the local mastless two-boom triangular sail (Figure 52).