Proceedings, the 51St Annual Meeting, 1975

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings, the 50Th Annual Meeting, 1974

proceedings of tl^e ai^i^iVepsapy EQeetiiig national association of schools of music NUMBER 63 MARCH 1975 NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOLS OF MUSIC PROCEEDINGS OF THE 50 th ANNIVERSARY MEETING HOUSTON, TEXAS 1974 Published by the National Association of Schools of Music 11250 Roger Bacon Drive, No. 5 Reston, Virginia 22090 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUE NUMBER 58-38291 COPYRIGHT ® 1975 NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOLS OF MUSIC 11250 ROGER BACON DRIVE, NO. 5, RESTON, VA. 22090 All rights reserved including the right to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form. CONTENTS Officers of the Association 1975 iv Commissions 1 National Office 1 Photographs 2-8 Minutes of the Plenary Sessions 9-18 Report of the Community/Junior College Commission Nelson Adams 18 Report of the Commission on Undergraduate Studies J. Dayton Smith 19-20 Report of the Commission on Graduate Studies Himie Voxman 21 Composite List of Institutions Approved November 1974 .... 22 Report of the Library Committee Michael Winesanker 23-24 Report of the Vice President Warner Imig 25-29 Report of the President Everett Timm 30-32 Regional Meeting Reports 32-36 Addresses to the General Session Welcoming Address Vance Brand 37-41 "Some Free Advice to Students and Teachers" Paul Hume 42-46 "Teaching in Hard Times" Kenneth Eble 47-56 "The Arts and the Campus" WillardL. Boyd 57-62 Papers Presented at Regional Meetings "Esthetic Education: Dialogue about the Musical Experience" Robert M. Trotter 63-65 "Aflfirmative Action Today" Norma F. Schneider 66-71 "Affirmative Action" Kenneth -

The John and Anna Gillespie Papers an Inventory of Holdings at the American Music Research Center

The John and Anna Gillespie papers An inventory of holdings at the American Music Research Center American Music Research Center, University of Colorado at Boulder The John and Anna Gillespie papers Descriptive summary ID COU-AMRC-37 Title John and Anna Gillespie papers Date(s) Creator(s) Repository The American Music Research Center University of Colorado at Boulder 288 UCB Boulder, CO 80309 Location Housed in the American Music Research Center Physical Description 48 linear feet Scope and Contents Papers of John E. "Jack" Gillespie (1921—2003), Professor of music, University of California at Santa Barbara, author, musicologist and organist, including more than five thousand pieces of photocopied sheet music collected by Dr. Gillespie and his wife Anna Gillespie, used for researching their Bibliography of Nineteenth Century American Piano Music. Administrative Information Arrangement Sheet music arranged alphabetically by composer and then by title Access Open Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the American Music Research Center. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], John and Anna Gillespie papers, University of Colorado, Boulder Index Terms Access points related to this collection: Corporate names American Music Research Center - Page 2 - The John and Anna Gillespie papers Detailed Description Bibliography of Nineteenth-Century American Piano Music Music for Solo Piano Box Folder 1 1 Alden-Ambrose 1 2 Anderson-Ayers 1 3 Baerman-Barnes 2 1 Homer N. Bartlett 2 2 Homer N. Bartlett 2 3 W.K. Bassford 2 4 H.H. Amy Beach 3 1 John Beach-Arthur Bergh 3 2 Blind Tom 3 3 Arthur Bird-Henry R. -

Proceedings, the 39Th Annual Meeting, 1963

FEBRU ARY 1964 •yu ] ATIONAL ASSOC lATION OF SCHOOLS OF MUSIC / \ Bulletin NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOLS OF MUSIC PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTY-NINTH ANNUAL MEETING NOVEMBER 1963 CHICAGO NUMBER 52 FEBRUARY 1964 Bulletin of the NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOLS OF MUSIC CARL M. NEUMEYER Editor Published by the National Association of Schools of Music Office of Secretary, Thomas W. Williams Knox College, Galesburg, Illinois CONTENTS Officers of the Association, 1964 v Commission Members, 1964 v Committees, 1964 vi President's Report, C. B. Hunt, fr 9 The Commission on the Humanities: A Progress Report, Gustave A. Arlt 15 Music in the University, Leigh Gerdine, Panel Chairman 27 Music in General Education, LdVahn Maesch 33 Relationship of Undergraduate to Graduate Studies, Scott Goldthwaite 38 General Education in Music, Robert Trotter. 43 Report of the Commission on Curricula 47 Report of the Graduate Commission 50 Report of the Commission on Ethics 58 Report of the Secretary 58 Report of the Treasurer 60 Report on Regional Meetings 60 Report of the Development Council 6l Report of the Nominating Committee 63 Report of the Publicity Committee. 64 Meetings of Standing Committees 64 By-Law Revisions - 65 Citation to Colonel Samuel Rosenbaum. 66 Thirty-Ninth Annual Meeting 66 In Honor of Howard Hanson 67 OFFICERS OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR 1964 President: C. B. Hunt, Jr., George Peabody College First Vice-President: Duane Branigan, University of Illinois Second Vice-President: LaVahn Maesch, Lawrence College Secretary: Thomas W. Williams, Knox College Treasurer: Carl M. Neumeyer, Illinois Wesleyan University Regional Chairmen: Region 1. J. Russell Bodley, University of the Pacific Region 2. -

Volume 65, Number 08 (August 1947) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 8-1-1947 Volume 65, Number 08 (August 1947) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 65, Number 08 (August 1947)." , (1947). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/181 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. XUQfr JNftr o 10 I s vation Army Band, has retired, after an AARON COPLAND’S Third Symphony unbroken record of sixty-four years’ serv- and Ernest Bloch’s Second Quartet have ice as Bandmaster in the Salvation Army. won the Award of the Music Critics Cir- cle of New York as the outstanding music American orchestral and chamber THE SALZBURG FESTI- BEGINNERS heard for the first time in New York VAL, which opened on PIANO during the past season. YOUNG July 31, witnessed an im- FOB portant break with tra- JOHN ALDEN CARPEN- dition when on August TER, widely known con- 6 the world premiere of KEYBOARD TOWN temporary American Gottfried von Einem’s composer, has been opera, “Danton’s Tod,” By Louise Robyn awarded the 1947 Gold was produced. -

Who Is Paule Maurice?? Her Relative Anonymity and Its Consequences

WHO IS PAULE MAURICE? HER RELATIVE ANONYMITY AND ITS CONSEQUENCES by Anthony Jon Moore A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL December 2009 Copyright © Anthony Jon Moore 2009 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere and deep appreciation to the many people who fielded my incessant queries and one-track mind conversations for the last two years, especially Dr. Kenneth Keaton, Dr. Laura Joella, Dr. Stuart Glazer, and my translator, Elsa Cantor. The unbelievable support that materialized from individuals I never knew existed is testimony to the legacy left behind by the subject of this thesis. I want to extend my heartfelt appreciation to Jean-Marie Londeix for responding to my many emails; Sophie Levy, Archivist of the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris for providing me with invaluable information; Marshall Taylor for donating his letter from Paule Maurice and his experiences studying Tableaux de Provence with Marcel Mule; Claude Delangle for Under the Sign of the Sun; James Umble for his book, Jean-Marie Londeix: Master of the Modern Saxophone; and Theodore Kerkezos for his videos of Tableaux de Provence. I want to thank Dr. Eugene Rousseau, Professor Emeritus Jack Beeson, Sarah Field, the Clarinet and Saxophone Society of Great Britain, Dr. Julia Nolan, Dr. Pamela Youngdahl Dees, Dr. Carolyn Bryan, and Dr. William Street, for generously taking a call from a stranger in search of Paule Maurice. -

Native American Elements in Piano Repertoire by the Indianist And

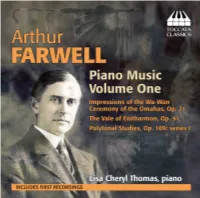

NATIVE AMERICAN ELEMENTS IN PIANO REPERTOIRE BY THE INDIANIST AND PRESENT-DAY NATIVE AMERICAN COMPOSERS Lisa Cheryl Thomas, B.M.E., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2010 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Steven Friedson, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Jesse Eschbach, Chair of the Division of Keyboard Studies Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Michael Monticino, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Thomas, Lisa Cheryl. Native American Elements in Piano Repertoire by the Indianist and Present-Day Native American Composers. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2010, 78 pp., 25 musical examples, 6 illustrations, references, 66 titles. My paper defines and analyzes the use of Native American elements in classical piano repertoire that has been composed based on Native American tribal melodies, rhythms, and motifs. First, a historical background and survey of scholarly transcriptions of many tribal melodies, in chapter 1, explains the interest generated in American indigenous music by music scholars and composers. Chapter 2 defines and illustrates prominent Native American musical elements. Chapter 3 outlines the timing of seven factors that led to the beginning of a truly American concert idiom, music based on its own indigenous folk material. Chapter 4 analyzes examples of Native American inspired piano repertoire by the “Indianist” composers between 1890-1920 and other composers known primarily as “mainstream” composers. Chapter 5 proves that the interest in Native American elements as compositional material did not die out with the end of the “Indianist” movement around 1920, but has enjoyed a new creative activity in the area called “Classical Native” by current day Native American composers. -

California Letters of Lucius Fairchild

California letters of Lucius Fairchild PUBLICATIONS OF THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN EDITED BY JOSEPH SCHAFER SUPERINTENDENT OF THE SOCIETY CALIFORNIA LETTERS OF LUCIUS FAIRCHILD WISCONSIN HISTORICAL PUBLICATIONS COLLECTIONS VOLUME XXXI SARGENT's PORTRAIT OF GENERAL LUCIUS FAIRCHILD (Original in the State Historical Museum, Madison) CONSIN HISTORICAL PUBLICATIONS COLLECTIONS VOLUME XXXI CALIFORNIA LETTERS OF LUCIUS FAIRCHILD EDITED WITH NOTES AND INTRODUCTION BY JOSEPH SCHAFER SUPERINTENDENT OF THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN PUBLISHED BY THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN MADISON, 1931 COPYRIGHT, 1931, BY THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN California letters of Lucius Fairchild http://www.loc.gov/resource/calbk.004 THE ANTES PRESS EVANSVILLE, WISCONSIN v INTRODUCTION The letters herewith presented have a two-fold significance. On the one hand, as readers will be quick to discern, they constitute a new and vivid commentary upon the perennially interesting history of the gold rush and life in the California mines. To be sure their author, like nearly all of those upon whose narratives our knowledge of conditions in the gulches and on the river bars of the Golden State depends, wrote as an eager gold seeker busily panning, rocking, or sluicing the sands of some hundred foot mining claim. His picture of California, at any given moment, had to be generalized, so to speak, from the “color” at the bottom of his testing pan. His particular camp, company, or environmental coup symbolized for him the prevailing conditions social, economic, and moral. While this was inevitable, it was by no means a misfortune, for a certain uniformity prevailed throughout the mining field and the witness who by intensive living gained a true insight into a given unit had qualifications for interpreting the entire gold digging society. -

Doctor of Musical Arts

In the Fingertips: A Discussion of Stravinsky’s Violin Writing in His Ballet Transcriptions for Violin and Piano A document submitted to the Graduate school of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Division of Performance Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music May 2012 by Kuan-Chang Tu B.F.A. Taipei National University of the Arts, 2001 M.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 2005 Advisor: Piotr Milewski, D.M.A. Abstract Igor Stravinsky always embraced the opportunity to cast his music in a different light. This is nowhere more evident than in the nine pieces for violin and piano extracted from his early ballets. In the 1920s, the composer rendered three of these himself; in the 1930s, he collaborated on five of them with Polish-American violinist Samuel Dushkin; and in 1947, he wrote his final one for French violinist Jeanne Gautier. In the process, Stravinsky took an approach that deviated from traditional recasting. Instead of writing thoroughly playable music, Stravinsky chose to recreate in the spirit of the instrument, and the results are mixed. The three transcriptions from the 1920s are extremely awkward and difficult to play, and thus rarely performed. The six later transcriptions, by contrast, apply much more logically to the instrument and remain popular in the violin literature. While the history of these transcriptions is fascinating and vital for a fuller understanding, this document has a more pedagogical aim. That is, it intends to use Stravinsky and these transcriptions as guidance and advice for future composers who write or arrange for the violin. -

Fostering Artistry and Pedagogy: Conversations with Artist-Teachers Frederick Hemke, Eugene Rousseau, and Donald Sinta

FOSTERING ARTISTRY AND PEDAGOGY: CONVERSATIONS WITH ARTIST-TEACHERS FREDERICK HEMKE, EUGENE ROUSSEAU, AND DONALD SINTA by Julia Nolan A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Curriculum Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2012 © Julia Nolan, 2012 ABSTRACT This research presents three case studies that explore university teachers in the private music studio and in the master class setting, framed by one central question: how do artist-teachers articulate, negotiate, and give shape to their pedagogical practices about artistry and interpretation within the context of private music education? The cases focus on saxophone artist-teachers Frederick Hemke at Northwestern University, Eugene Rousseau at the University of Minnesota, and Donald Sinta at the University of Michigan. I analyzed instrumental music performance teaching and learning from the perspective of the three artist-teachers. The data collected from interviews, observations, and my personal narratives provide a rich resource for the analysis of the professional lives of master musicians, their pedagogies, and their thoughts about artistry in music performance and instruction. Interviews with many of the artist-teachers’ students also informed my analysis. More important, this study connects present and future saxophonists by capturing the voices of recognized artist-teachers about artistry and pedagogy. Central to this thesis are the discovery of how little has changed in the concepts of artistry and pedagogy over time and across the evolution of musical styles, and recognition of the power of the strong bonds that connect generations of students with their teachers and their teachers’ teachers. -

Ne\\- Society Initiates to Wear Flowers American Soprano Will Sing Concert at First Wellesley

elleGtcn «allege News XLV 2 3 1 1 WELLESLEY, MASS., OCTOBER 16, 1941 No. 4 Ne\\- Society Mr s. Vera M. Dean Mr. Hogan 'fo Give American Soprano Will Sing Initiates To T o Give Lectures Econo1nic Report At First Wellesley Concert In History Forum Professor Will Comment Wear Flowers An objective view of the strate On Industr ial Future Mme. Helen Traube! P lans gic points of the world situation Of New England Recital of Classics, Six Societies Give Roses will be presented by the History "Will New England lose the Spiritual Songs To Newest Members From Department in the form of a His woolen and worsted industries in Familiar to all members of the tory Forum, October 27, 28, and 29, the post-war period?" is the ques musical world, Mme. Helen Trau Classes of 1942-1343 be! will sing for her first Welles under the leadership of Mrs. Vera tion which Mr . John Hogan, New members of Vlellesley's six Professor of Labor Economics at ley audience at 8:30 p.m. this eve societies r eceived early this morn Micheles Dean, director of the Radcliffe College will answer at the ning in Alumnae Hall at the ini ing roses signifying their election, Foreign Policy Association research Economics Department dinner, Oc tial concert of the college series. along with a picture of their society department and editor of its pub tober 21, at 6 :30 p. m . in the small Mme. Traubel, who made her debut two years ago in New York, is a house and their society "family lications. -

Councilmembers Seek Renomination. 2Nd Ward Contest

Re3 Cross Drive March 1-31 Reel Cross Drive March 1-3 i 56th YEAR, No. 39 SUMMIT, N. J., THURSDAY, MARCH 4, 1945 IJAYlAfc * CENTS CouncilMembers For Mayor Summit A.W.V5. Former Overlook Nurses Art Stcend LieufenonH In Army Nurte Corps Slum Clearance Red Cross Reports Seek Renomination. Dissolves Unit; 2nd Ward Contest And Housing Topic 526,000 First Week Petitions ar» now in circulation Joins State Hdqs. Of Women Voters Of War Fund Drive f«r Councilman-st-large Ernest S. At a meeting of the Summit "Slum Clearance aad Low In- A total of $2tS,OOQ, which ia near* Hsekok and Councilman Louii G. Unit, AWVS held on January 15, some Housing" will b« the Jsubjeet ly 30 percent of its quota of J75 OOfl Dapero of the Second Ward as can- it was decided by the entire mem- of.-. the Mai fh meeting of the was reported % Summit Chapter, bership present, that, because of didate for renomiaation to their League of Women Voter* icto he American Red Cro-.*, yesterday respectiv* pcwU ia the Jun» 12 lack of continuous services to be held Monday, March* 1- at the av»rninjr for the fir.--t wtek of fha' performed, the Summit Unit primary on the Republican ticket. Mt'thoiiiH Church-'parish hoiwr at War Fund which Councilman Dapero faces opposi- I should become a atate extension 2 p. m. continue throughout March, and members should pay their tion because petition* are being Mrs. Gertrude Gross, Overseer All groups active In the driv* circulated for .Eugene F. Daly of duea directly.to New Jersey State Headquarters- and receive assign- of the Poor and director of relief, have either completed their pre» Pearl street who seeks the nom- ments from there. -

Toccata Classics TOCC 0126 Notes

ARTHUR FARWELL: PIANO MUSIC, VOLUME ONE by Lisa Cheryl Thomas ‘he evil that men do lives ater them’, says Mark Antony in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar; ‘he good is ot interred with their bones.’ Luckily, that isn’t true of composers: Schubert’s bones had been in the ground for over six decades when the young Arthur Farwell, studying electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, heard the ‘Uninished’ Symphony for the irst time and decided that he was going to be not an engineer but a composer. Farwell, born in St Paul, Minnesota, on 23 March 1872,1 was already an accomplished musician: he had learned the violin as a child and oten performed in a duo with his pianist elder brother Sidney, in public as well as at home; indeed, he supported himself at college by playing in a sextet. His encounter with Schubert proved detrimental to his engineering studies – he had to take remedial classes in the summer to be able to pass his exams and graduated in 1893 – but his musical awareness expanded rapidly, not least through his friendship with an eccentric Boston violin prodigy, Rudolph Rheinwald Gott, and frequent attendance at Boston Symphony Orchestra concerts (as P a ‘standee’: he couldn’t aford a seat). Charles Whiteield Chadwick (1854–1931), one of the most prominent of the New England school of composers, ofered compositional advice, suggesting, too, that Farwell learn to play the piano as soon as possible. Edward MacDowell (1860–1908), perhaps the leading American Romantic composer of the time, looked over his work from time to time – Farwell’s inances forbade regular study with such an eminent igure, but he could aford counterpoint lessons with the organist Homer Albert Norris (1860–1920), who had studied in Paris with Dubois, Gigout and Guilmant, and piano lessons with homas P.