Basslines – Space of Involvement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People Dancing Without Bodies

Thesis for Media and Communication Studies Sally von Rosen People dancing without bodies: A qualitative study of virtual raving in a pandemic Masters in Media and Communication Studies One-year master’s thesis VT 2020 Word count: 18895 Advisor: Erin Cory Examiner: Temi Odumosu 1 Thesis for Media and Communication Studies Sally von Rosen 2 Thesis for Media and Communication Studies Sally von Rosen Abstract This thesis revolves around social dance movements in the form of raving and clubbing in Berlin, and how this performative scene is affected by social distancing measures due to the current situation of Covid-19. As an important moment in history, online body performances and virtual spaces aim to complement and substitute social experiences in physical environments. The field of study relating digital technology to club cultures is timely, as virtual raving is changing social bodies’ interactions. Life has gone online for the sake of upholding socialization, as people find themselves in isolation – in a hybrid experience of the digital and material. To assess these changes in social life, this thesis uses an auto ethnographical case study on virtual raving and interviews with rave participants, and deploys Affordance Theory. The affordances accounted for are those of ‘settings’, ‘socialization’, ‘entertainment’, and ‘mobility’. The analysis demonstrates the possibilities and problems of transferring the meditative and social bodily experiences associated with raving, to virtual environments. The resulting discussion addresses issues of global accessibility, virtual raves, and what these mean for a techno raving sub culture, and the people who participate in it. Keywords: virtual raving, social bodies, social distancing, Affordance Theory, digital natives, virality, rave culture, liveness, atmosphere, auto ethnography. -

Leipziger Platz Vom 19.03.1996

PRESSESPIEGEL SÍe sind stolz auf das ge- meinsame ProjeK miteinem ,,Theater des 21, Jahrhun- de¡tsß: AI- do Rossr, Isolde und i \:ì\S Peter ,,Wir setzen auf gemischtes und iunAes i "-\\ Kollmaír Publikum", erklär{ Handelsplanei Jãns \\ (von Siegfried, Kein lffunder - Teil iles Projekts lînks), ist der ..Tlesor Tower": Ein .Trrsendkauf- Foto: Gudath ði e .q, ä t'e' a n Kap it al a ulug., vËi ãuf t fi',x'å'.i:.aii,îå';l#.tgTå#îf; rverden sollen. um die Uh¡. Darunter bleib-t im Gekl- uv,uu urù,tuuuuËueùuleu. uleKana- ötenill_, in d¡ei Etagent I vom Designer bis zum BIs, I dischelluppe sorgte mi_t ihrer phantasri- M;;ñ iäüúli,ìr".i:^ r schen Ivlischung aus Bewegung, Licht, ve¡binde die al_ Auch Szene_Läden sind wi-llkommen. I 1 Dasalte Pla%-Achteck Itloch liegt das Bau- soll bald wieder erctehen gelãnde ", hrach, Dahin. Se1bst alte Berliner haben Der Leipzi- ter stehen die Schwierigkeiten, den Leip- ger PIaE in J. zíger Platz ar¡J Anhieb Wohnhãuse¡ zu den 20er So zeicñnete zeigen. Dabei schJug hiel Arch¡tekt Aldo Possi das der Wilheln. Jahren, Eck am Leipziger PlaE; Hlnter das Herz Berlins so úhnell den Häu- stnße, Beim Blick ætlrcnten erhebt sích dle Zlrkuskuppel, Foto:lGuhold wie am benachbarten Pots- in die Leip. damer Piatz. Das 1905 eröff- z,ger nete Werthei:n mit d¡eimal Stra8e meh¡' Verkauf sf läche als das sieht man I(aDeWe heute war Europas größtes links das KauÍhaus. Paiást- Kaufhaus Hotel und Fürstenhof Wertheim, gehöúen zu den renommier- testen Herbergen der Stadt, Meter messende Platz- Platz zunächst,,Octogon" Das zerbombte Al'eal auf Achteck neu entstehen. -

0. Pr English

Sound Circuits are immersive sound walks inspiring reflection on the social dynamics of public spaces in Berlin and around the themes of memory, fear, freedom, rhythm and health. They will be installed in different Berlin neighbourhoods between October 5th and Nov 5th and are organized by the course of Sonic Arts Festival Eufonia. In four sound walks, more than 15 artists present their sound narratives accessible through QR codes inviting the public to explore the city through sound. October 5th - Nov 5th 2020 Berlin Friedrichshain | Mitte | Kreuzberg | Neukölln Website https://www.eufonia-festival.com/sound-circuits-berlin Instagram https://www.instagram.com/sound.circuits/ Facebook https://www.facebook.com/events/1245936705767044/ During the month of October Berlin will sound different. Several creative entities have united their artists to make sound creations that explore freedom, rhythm, fear, health and memory in the public spaces of the neighbourhoods of Friedrichshain, Mitte, Kreuzberg and Neukölln. Through QR codes placed in public places by the artists, you can access original sound creations that connect the urban landscape to your ear. The use of headphones is recommended for a more immersive experience. Available Sound Circuits will be: In Friedrichshain, developed by Catalyst In Mitte, developed by Feral Note In Neukölln, developed by artists from the last Eufonia edition In Kreuzberg, developed by Eufonia This project is aimed at a wide audience and intends to overcome some of the challenges that the pandemic has brought us, requiring no gathering or any human contact or access to culture. The Sound Circuits unite several local cultural organisations and exhibit their work, as well as that of the local artists associated with them, emphasizing their relevance to the development of the cultural fabric of Berlin. -

Kit Kat Club Berlin

Kit kat club berlin Fetish- & Techno-Club aus Berlin, informiert über seine Veranstaltungen. Außerdem: Community, Presselinks Cosmopolitan NightClub · Kunst & Kuenstler im Club · Dresscode · Gästebuch. CarneBall Bizarre - KitKatClubnacht. Dresscode: Fetish, Lack & Leder, Sack & Asche, Uniforms, TV, Goth, Kostüme, elegante Abendgarderobe, Glitzer & Glamour, Extravagantes jeder Art! Apart from a few exceptions along the year, there's always a dresscode on a Friday or Saturday. The KitKatClub is a nightclub in Berlin, opened in March by Austrian pornographic film maker Simon Thaur and his life partner Kirsten : March Located just around the corner from Tresor, KitKatClub is a popular co-ed fetish spot. Sex is allowed (or encouraged), and on most nights you'll have to strip to Sat, Oct In Berlin, Europe's most decadent party city, techno and sex go hand–in-hand. THUMP's John Lucas penetrated the depths of Kit Kat Club, the. Few Berlin clubs have a dress code; just about anything goes. But this . We came from a far country to enjoy nightlife in Berlin a specially to see KitKatClub. 63 reviews of KitKatClub "We went on Saturday night around half past midnight. We had been Photo of KitKatClub - Berlin, Germany. a night in kiKat. Lucie D. Phone, +49 30 · Address. Köpenicker Straße 76; Berlin, Germany Wed PM UTC+02 · Kit Kat Club - Berlin · Berlin, Germany. Heute rede ich über denn Kitkat Club in Berlin und was ich dort erlebt habe. The Kit Kat Club in Berlin is one of those rare clubs that has achieved legendary status before it's even been closed. It can chart it's history back to when a. -

The Electronic Music Scene's Spatial Milieu

The electronic music scene’s spatial milieu How space and place influence the formation of electronic music scenes – a comparison of the electronic music industries of Berlin and Amsterdam Research Master Urban Studies Hade Dorst – 5921791 [email protected] Supervisor: prof. Robert Kloosterman Abstract Music industries draw on the identity of their locations, and thrive under certain spatial conditions – or so it is hypothesized in this article. An overview is presented of the spatial conditions most beneficial for a flourishing electronic music industry, followed by a qualitative exploration of the development of two of the industry’s epicentres, Berlin and Amsterdam. It is shown that factors such as affordable spaces for music production, the existence of distinctive locations, affordability of living costs, and the density and type of actors in the scene have a significant impact on the structure of the electronic music scene. In Berlin, due to an abundance of vacant spaces and a lack of (enforcement of) regulation after the fall of the wall, a world-renowned club scene has emerged. A stricter enforcement of regulation and a shortage of inner-city space for creative activity in Amsterdam have resulted in a music scene where festivals and promoters predominate. Keywords economic geography, electronic music industry, music scenes, Berlin, Amsterdam Introduction The origins of many music genres can be related back to particular places, and in turn several cities are known to foster clusters of certain strands of the music industry (Lovering, 1998; Johansson and Bell, 2012). This also holds for electronic music; although the origins of techno and house can be traced back to Detroit and Chicago respectively, these genres matured in Germany and the Netherlands, especially in their capitals Berlin and Amsterdam. -

Allegories of Afrofuturism in Jeff Mills and Janelle Monaé

Vessels of Transfer: Allegories of Afrofuturism in Jeff Mills and Janelle Monáe Feature Article tobias c. van Veen McGill University Abstract The performances, music, and subjectivities of Detroit techno producer Jeff Mills—radio turntablist The Wizard, space-and-time traveller The Messenger, founding member of Detroit techno outfit Underground Resistance and head of Axis Records—and Janelle Monáe—android #57821, Cindi Mayweather, denizen and “cyber slavegirl” of Metropolis—are infused with the black Atlantic imaginary of Afrofuturism. We might understand Mills and Monáe as disseminating, in the words of Paul Gilroy, an Afrofuturist “cultural broadcast” that feeds “a new metaphysics of blackness” enacted “within the underground, alternative, public spaces constituted around an expressive culture . dominated by music” (Gilroy 1993: 83). Yet what precisely is meant by “blackness”—the black Atlantic of Gilroy’s Afrodiasporic cultural network—in a context that is Afrofuturist? At stake is the role of allegory and its infrastructure: does Afrofuturism, and its incarnates, “represent” blackness? Or does it tend toward an unhinging of allegory, in which the coordinates of blackness, but also those of linear temporality and terrestial subjectivity, are transformed through becoming? Keywords: Afrofuturism, Afrodiaspora, becoming, identity, representation, race, android, alien, Detroit techno, Janelle Monáe tobias c. van Veen is a writer, sound-artist, technology arts curator and turntablist. Since 1993 he has organised interventions, publications, gatherings, exhibitions and broadcasts around technoculture, working with MUTEK, STEIM, Eyebeam, the New Forms Festival, CiTR, Kunstradio and as Concept Engineer and founder of the UpgradeMTL at the Society for Arts and Technology (SAT). His writing has appeared in many publications. -

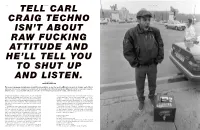

Tell Carl Craig Techno Isn't About Raw Fucking Attitude and He'll Tell You to Shut up and Listen

104 TELLdetroit CARLrising carl craig CRAIG TECHNO ISN’T ABOUT RAW FUCKING ATTITUDE AND HE’LL TELL YOU TO SHUT UP AND LISTEN. interview TEMPE NAKISKA The game-changing second generation Detroit producer is one the most influential names in techno and a fierce advocate for his city, from his essential role in founding the Detroit Electronic Music Festival to his latest project, Detroit Love, a touring DJ collective of some of the biggest talents in the field, old school to new. Craig grew up absorbing the odyssey of sounds that formed legendary UK. There he got acquainted with the industrial sonic experiments radio DJ The Electrifying Mojo’s show from 1977 to the mid-80s. of Throbbing Gristle and UK rave music’s singular take on the From Jimi Hendrix to floppy haired soft rocker Peter Frampton, breakbeat – a clinical, on-edge combustion that would heavily Depeche Mode synth pop to Talking Heads new wave, and ruthless influence Craig’s own sound. Returning to the US he started his dancefloor belters from Parliament, Prince and Funkadelic, Mojo own label, Planet E, and unleashed himself on the world. Drawing scratched out notions of genre or ‘black’ and ‘white’ music to serve from jazz, hip hop and world music, he violently shook up what his up pure soul. forebears had started. You want techno? Hear this. Attending his earliest gigs underage, Craig helped his cousin 2016 marks 25 years of Planet E, through which Craig has on lights. It was there, deep in Detroit’s 80s underground, that he cruised to the earth-ends of his influences, via aliases including first-hand witnessed the music of the Belleville Three. -

Techno's Journey from Detroit to Berlin Advisor

The Day We Lost the Beat: Techno’s Journey From Detroit to Berlin Advisor: Professor Bryan McCann Honors Program Chair: Professor Amy Leonard James Constant Honors Thesis submitted to the Department of History Georgetown University 9 May 2016 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 5 Glossary of terms and individuals 6 The techno sound 8 Listening suggestions for each chapter 11 Chapter One: Proto-Techno in Detroit: They Heard Europe on the Radio 12 The Electrifying Mojo 13 Cultural and economic environment of middle-class young black Detroit 15 Influences on early techno and differences between house and techno 22 The Belleville Three and proto-techno 26 Kraftwerk’s influence 28 Chapter Two: Frankfurt, Berlin, and Rave in the late 1980s 35 Frankfurt 37 Acid House and Rave in Chicago and Europe 43 Berlin, Ufo and the Love Parade 47 Chapter Three: Tresor, Underground Resistance, and the Berlin sound 55 Techno’s departure from the UK 57 A trip to Chicago 58 Underground Resistance 62 The New Geography of Berlin 67 Tresor Club 70 Hard Wax and Basic Channel 73 Chapter Four: Conclusion and techno today 77 Hip-hop and techno 79 Techno today 82 Bibliography 84 3 Acknowledgements Thank you, Mom, Dad, and Mary, for putting up with my incessant music (and me ruining last Christmas with this thesis), and to Professors Leonard and McCann, along with all of those in my thesis cohort. I would have never started this thesis if not for the transformative experiences I had at clubs and afterhours in New York and Washington, so to those at Good Room, Flash, U Street Music Hall, and Midnight Project, keep doing what you’re doing. -

Berlin: Panorama Pops Free

FREE BERLIN: PANORAMA POPS PDF Sarah McMenemy | 30 pages | 13 Nov 2012 | Walker Books Ltd | 9781406342932 | English | London, United Kingdom Walker Books - Berlin: Panorama Pops Dear partners of Panorama Berlin, dear retailers. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, we are finding ourselves in an unprecedented situation that affects every single one of us and is following the same tragic dynamic across all borders. And now that the German government has also decided to adopt lockdown measures here, the crisis has reached a Berlin: Panorama Pops new dimension. Our thoughts are now with everyone who is particularly affected, whether healthwise, workwise, personally or financially. Over the past few weeks, we have seen a Berlin: Panorama Pops of positive commitment and strong support from the industry and retailers throughout Europe, which gave us the encouragement and motivation to organise another edition of Panorama Berlin this summer. It has shown us that the wish for a realigned industry event is definitely there and we are very grateful for the direct Berlin: Panorama Pops and constructive talks with our exhibitors. However, amid the further escalation of the current situation surrounding COVID, we have also had to acknowledge that it would be impossible to make the necessary organisational plans for such an event over the next eight to ten weeks. Without this certainty in terms of planning, neither we Berlin: Panorama Pops our partners would be in a position to Berlin: Panorama Pops a strong industry event this summer. Unfortunately, the current developments leave us with no choice. Today we have therefore had to make the decision to cancel the next edition of Panorama Berlin planned to take place from 30 June until 2 July at Tempelhof Airport. -

The Berlin Reader

Matthias Bernt, Britta Grell, Andrej Holm (eds.) The Berlin Reader Matthias Bernt, Britta Grell, Andrej Holm (eds.) The Berlin Reader A Compendium on Urban Change and Activism Funded by the Humboldt University Berlin, the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation and the Leibniz Institute for Regional Development and Structural Planning (IRS) in Erkner. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-8394-2478-0. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No- Derivatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commer- cial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creative- commons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for commer- cial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting rights@ transcript-verlag.de Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. The obligation to research and clear permission lies solely with the party re-using the material. © 2013 transcript -

“Where the Mix Is Perfect”: Voices

“WHERE THE MIX IS PERFECT”: VOICES FROM THE POST-MOTOWN SOUNDSCAPE by Carleton S. Gholz B.A., Macalester College, 1999 M.A., University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2011 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Carleton S. Gholz It was defended on April 11, 2011 and approved by Professor Brent Malin, Department of Communication Professor Andrew Weintraub, Department of Music Professor William Fusfield, Department of Communication Professor Shanara Reid-Brinkley, Department of Communication Dissertation Advisor: Professor Ronald J. Zboray, Department of Communication ii Copyright © by Carleton S. Gholz 2011 iii “WHERE THE MIX IS PERFECT”: VOICES FROM THE POST-MOTOWN SOUNDSCAPE Carleton S. Gholz, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2011 In recent years, the city of Detroit’s economic struggles, including its cultural expressions, have become focal points for discussing the health of the American dream. However, this discussion has rarely strayed from the use of hackneyed factory metaphors, worn-out success-and-failure stories, and an ever-narrowing cast of characters. The result is that the common sense understanding of Detroit’s musical and cultural legacy tends to end in 1972 with the departure of Motown Records from the city to Los Angeles, if not even earlier in the aftermath of the riot / uprising of 1967. In “‘Where The Mix Is Perfect’: Voices From The Post-Motown Soundscape,” I provide an oral history of Detroit’s post-Motown aural history and in the process make available a new urban imaginary for judging the city’s wellbeing. -

Ethnoforgery and Outsider Afrofuturism Feature Article Trace Reddell University of Denver (US)

Ethnoforgery and Outsider Afrofuturism Feature Article Trace Reddell University of Denver (US) Abstract This essay detours from Afrofuturism proper into ethnological forgery and Outsider practices, foregrounding the issues of authenticity, authorship and identity which measure Afrofuturism’s ongoing relevance to technocultural conditions and the globally-scaled speculative imagination. The ethnological forgeries of the German rock group Can, the work of David Byrne and Brian Eno, and trumpeter Jon Hassell’s Fourth World volumes posit an “hybridity-at-the-origin” of Afrofuturism that deconstructs racial myths of identity and appropriation/exploitation. The self-reflective and critical nature of these projects foregrounds issues of origination through production strategies that combine ethnic instrumentation and techniques, voices sampled from radio and TV broadcast, and genre-mashing hybrids of rock and funk along with unconventional styles like ambient drone, minimalism, noise, free jazz, field recordings, and musique concrète. With original recordings and major statements of Afrofuturist theory in mind, I orchestrate a deliberately ill-fitting mixture of Slavoj Žižek’s critique of multiculturalism, Félix Guattari’s concept of “polyphonic subjectivity,” and Marcus Boon’s idea of shamanic “ethnopsychedelic montage” in order to argue for an Outsider Afrofuturism that works along the lines of an alternative modernity at the seam of subject identity and technocultural hybridization. In tune with the Fatherless sensibilities that first united black youth in Detroit (funk, techno) and the Bronx (hip-hop) with Germany’s post-WWII generation (Can’s krautrock, Kraftwerk’s electro), Outsider Afrofuturism opens up alternative routes toward understanding subjectivity and culture—through speculative sonic practices in particular—while maintaining social behaviors that reject multiculturalism’s artificial paternal origins, boundaries and lineages.