“Where the Mix Is Perfect”: Voices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

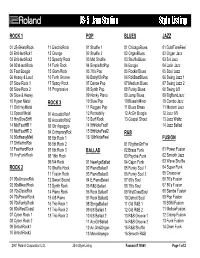

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing ROCK 1 POP BLUES JAZZ 01 JS-5HardRock 11 ElectricRock 01 Shuffle 1 01 ChicagoBlues 01 DublTimeFeel 02 BritHardRck1 12 Grunge 02 Shuffle 2 02 OrganBlues 02 Organ Jazz 03 BritHardRck2 13 Speedy Rock 03 Mid Shuffle 03 ShuffleBlues 03 5/4 Jazz 04 80'sHardRock 14 Funk Rock 04 Simple8btPop 04 Boogie 04 Latin Jazz 05 Fast Boogie 15 Glam Rock 05 70's Pop 05 Rockin'Blues 05 Soul Jazz 06 Heavy & Loud 16 Funk Groove 06 Early80'sPop 06 RckBeatBlues 06 Swing Jazz 1 07 Slow Rock 1 17 Spacy Rock 07 Dance Pop 07 Medium Blues 07 Swing Jazz 2 08 Slow Rock 2 18 Progressive 08 Synth Pop 08 Funky Blues 08 Swing 6/8 09 Slow & Heavy 09 Honky Piano 09 Jump Blues 09 BigBandJazz 10 Hyper Metal ROCK 3 10 Slow Pop 10 BluesInMinor 10 Combo Jazz 11 Old HvyMetal 11 Reggae Pop 11 Blues Brass 11 Modern Jazz 12 Speed Metal 01 AcousticRck1 12 Rockabilly 12 AcGtr Boogie 12 Jazz 6/8 13 HvySlowShffl 02 AcousticRck2 13 Surf Rock 13 Gospel Shout 13 Jazz Waltz 14 MidFastHR 1 03 Gtr Arpeggio 14 8thNoteFeel1 14 Jazz Ballad 15 MidFastHR 2 04 CntmpraryRck 15 8thNoteFeel2 R&B 16 80sHeavyMetl 05 8bt Rock 1 16 16thNoteFeel FUSION 17 ShffleHrdRck 06 8bt Rock 2 01 RhythmGtrFnk 18 FastHardRock 07 8bt Rock 3 BALLAD 02 Brass Funk 01 Power Fusion 19 HvyFunkRock 08 16bt Rock 03 Psyche-Funk 02 Smooth Jazz 09 5/4 Rock 01 NewAgeBallad 04 Cajun Funk 03 Wave Shuffle ROCK 2 10 Shuffle Rock 02 PianoBallad1 05 Funky Soul 1 04 Super Funk 11 Fusion Rock 03 PianoBallad2 06 Funky Soul 2 05 Crossover 01 90sGrooveRck 12 Sweet Sound 04 E.PianoBalad 07 60's Soul 06 -

Steve Cropper | Primary Wave Music

STEVE CROPPER facebook.com/stevecropper twitter.com/officialcropper Image not found or type unknown youtube.com/channel/UCQk6gXkhbUNnhgXHaARGskg playitsteve.com en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steve_Cropper open.spotify.com/artist/1gLCO8HDtmhp1eWmGcPl8S If Yankee Stadium is “the house that Babe Ruth built,” Stax Records is “the house that Booker T, and the MG’s built.” Integral to that potent combination is MG rhythm guitarist extraordinaire Steve Cropper. As a guitarist, A & R man, engineer, producer, songwriting partner of Otis Redding, Eddie Floyd and a dozen others and founding member of both Booker T. and the MG’s and The Mar-Keys, Cropper was literally involved in virtually every record issued by Stax from the fall of 1961 through year end 1970.Such credits assure Cropper of an honored place in the soul music hall of fame. As co-writer of (Sittin’ On) The Dock Of The Bay, Knock On Wood and In The Midnight Hour, Cropper is in line for immortality. Born on October 21, 1941 on a farm near Dora, Missouri, Steve Cropper moved with his family to Memphis at the age of nine. In Missouri he had been exposed to a wealth of country music and little else. In his adopted home, his thirsty ears amply drank of the fountain of Gospel, R & B and nascent Rock and Roll that thundered over the airwaves of both black and white Memphis radio. Bit by the music bug, Cropper acquired his first mail order guitar at the age of 14. Personal guitar heroes included Tal Farlow, Chuck Berry, Jimmy Reed, Chet Atkins, Lowman Pauling of the Five Royales and Billy Butler of the Bill Doggett band. -

Music and Inter-Generational Experiences of Social Change in South Africa

All Mixed Up: Music and Inter-Generational Experiences of Social Change in South Africa Dominique Santos 22113429 PhD Social Anthropology Goldsmiths, University of London All Mixed Up: Music and Inter-Generational Experiences of Social Change in South Africa Dominique Santos 22113429 Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for a PhD in Social Anthropology Goldsmiths, University of London 2013 Cover Image: Party Goer Dancing at House Party Brixton, Johannesburg, 2005 (Author’s own) 1 Acknowledgements I owe a massive debt to a number of people and institutions who have made it possible for me to give the time I have to this work, and who have supported and encouraged me throughout. The research and writing of this project was made financially possible through a generous studentship from the ESRC. I also benefitted from the receipt of a completion grant from the Goldsmiths Anthropology Department. Sophie Day took over my supervision at a difficult point, and has patiently assisted me to see the project through to submission. John Hutnyk’s and Sari Wastel’s early supervision guided the incubation of the project. Frances Pine and David Graeber facilitated an inspiring and supportive writing up group to formulate and test ideas. Keith Hart’s reading of earlier sections always provided critical and pragmatic feedback that drove the work forward. Julian Henriques and Isaak Niehaus’s helpful comments during the first Viva made it possible for this version to take shape. Hugh Macnicol and Ali Clark ensured a smooth administrative journey, if the academic one was a little bumpy. Maia Marie read and commented on drafts in the welcoming space of our writing circle, keeping my creative fires burning during dark times. -

Effets & Gestes En Métropole Toulousaine > Mensuel D

INTRAMUROSEffets & gestes en métropole toulousaine > Mensuel d’information culturelle / n°383 / gratuit / septembre 2013 / www.intratoulouse.com 2 THIERRY SUC & RAPAS /BIENVENUE CHEZ MOI présentent CALOGERO STANISLAS KAREN BRUNON ELSA FOURLON PHILLIPE UMINSKI Éditorial > One more time V D’après une histoire originale de Marie Bastide V © D. R. l est des mystères insondables. Des com- pouvons estimer que quelques marques de portements incompréhensibles. Des gratitude peuvent être justifiées… Au lieu Ichoses pour lesquelles, arrivé à un certain de cela, c’est souvent l’ostracisme qui pré- cap de la vie, l’on aimerait trouver — à dé- domine chez certains des acteurs culturels faut de réponses — des raisons. Des atti- du cru qui se reconnaîtront. tudes à vous faire passer comme étranger en votre pays! Il faut le dire tout de même, Cependant ne généralisons pas, ce en deux décennies d’édition et de prosély- serait tomber dans la victimisation et je laisse tisme culturel, il y a de côté-ci de la Ga- cet art aux politiques de tous poils, plus ha- ronne des décideurs/acteurs qui nous biles que moi dans cet exercice. D’autant toisent quand ils ne nous méprisent pas tout plus que d’autres dans le métier, des atta- simplement : des organisateurs, des musi- ché(e)s de presse des responsables de ciens, des responsables culturels, des théâ- com’… ont bien compris l’utilité et la néces- treux, des associatifs… tout un beau monde sité d’un média tel que le nôtre, justement ni qui n’accorde aucune reconnaissance à inféodé ni soumis, ce qui lui permet une li- photo © Lisa Roze notre entreprise (au demeurant indépen- berté d’écriture et de publicité (dans le réel dante et non subventionnée). -

Word up Ezine Aug-Sep 2011.Indd

CULTURE MAGAZINE | 05 | Aug/Sept 2011 p2 ILLUSTRATION ARTICLES 2 . Die Drie Skelms 5 . Mamagoema – by Toni Stuart 13 . The time is NOW! – by DelaRoss SCULPTURE 22 . Prefi x – by Toni Stuart 10 . Shawn Smith – Pixel Lord 24 . Skaftien – by Nadine Christians MUSIC FEATURES 14 . Nadine Matthews EVENTS 30 . African Hip Hop Indaba 2011. 16 . QBA (Cuba) . 18 . Blaq Pearl 31 The Best of Ekapa Under Ground Hip Hop presents Ladies in Hip Hop 20 . DJ Hamma . 26 El Phoenix IN EVERY ISSUE 1 . Editor’s Letter PHOTOGRAPHY 28 . Movie Reviews 6 . Photos by Kent Lingeveldt 29 . Music Reviews . VERSE 32 In the Mix 25 . M. Coco Putuma – Woman 33 . On the Download/Directory p22 p6 AUGUST – SEPTEMBER 2011 / Issue NO. 5 [email protected] Co-founder / Editor Big Dré Co-founder / Creative Nash Contributing Writers Toni Stuart, Nadine Christians, DelaRoss and Arsenic Cover sculpture by Shawn Smith WORD UP EDITOR’S LETTER To the people over here, to the people If you or anyone else you may know over there... is talented, spread the magazine and the word. We welcome all submissions Word Up is down to support all kinds of creative expression (photos, graffiti, design, fine art, tattoo whether it’s, visual art, photography or music etc. Creative is creative! Why art, articles, music for reviews, etc.) I mention it is because I’m tired of people saying “this is real art” or “that’s Please help us make it easier to expose not real art”. It’s all real art, you may not prefer that particular artist, music your art. -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

Sonic Jihadâ•Flmuslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration

FIU Law Review Volume 11 Number 1 Article 15 Fall 2015 Sonic Jihad—Muslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration SpearIt Follow this and additional works at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/lawreview Part of the Other Law Commons Online ISSN: 2643-7759 Recommended Citation SpearIt, Sonic Jihad—Muslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration, 11 FIU L. Rev. 201 (2015). DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.25148/lawrev.11.1.15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by eCollections. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Law Review by an authorized editor of eCollections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 37792-fiu_11-1 Sheet No. 104 Side A 04/28/2016 10:11:02 12 - SPEARIT_FINAL_4.25.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 4/25/16 9:00 PM Sonic Jihad—Muslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration SpearIt* I. PROLOGUE Sidelines of chairs neatly divide the center field and a large stage stands erect. At its center, there is a stately podium flanked by disciplined men wearing the militaristic suits of the Fruit of Islam, a visible security squad. This is Ford Field, usually known for housing the Detroit Lions football team, but on this occasion it plays host to a different gathering and sentiment. The seats are mostly full, both on the floor and in the stands, but if you look closely, you’ll find that this audience isn’t the standard sporting fare: the men are in smart suits, the women dress equally so, in long white dresses, gloves, and headscarves. -

Genres, Stile Und Musikalische Strömungen Populärer Musik in Deutschland

Peter Wicke Genres, Stile und musikalische Strömungen populärer Musik in Deutschland Die populäre Musik hat sich in den letzten Jahrzehnten in eine unüberschaubare Vielfalt an Spielweisen und Stilformen ausdifferenziert. Dabei haben Genre- und Gattungsmodelle ihre normative Bindekraft verloren und einer im Prinzip grenzenlosen Individualisierung musikalischer Kreativität Raum gegeben. Andererseits liefern sie jedoch noch immer einen funktionellen Orientierungsrahmen für den Marketing-Prozess, der das ausufernde Angebot an Produktionen strukturiert und auf das Musikschaffen zurückwirkt. Der musikalische Inhalt der einschlägigen Begrifflichkeit hat sich dabei mit einer Vielzahl von außermusikalischen Aspekten – Nachfragestrukturen, Zielgruppen, Vertriebswegen, Kommunikationsstrategien, Medien- und Programm- formaten – verzahnt, die derartige Kategorien allenfalls noch als Grobraster tauglich machen. Hinter dieser Entwicklung haben sich zudem Musikformen wie etwa das unterhaltende Musiktheater in Form von Operet- te und Musical in ihren tradierten institutionellen Zusammenhängen behauptet, werden wie die Blasmusik und viele Laienmusikformen auf der Grundlage fester Traditionen erhalten oder sind wie die Film-, TV- und Werbemusik in eng definierte und damit relativ stabile Anwendungskontexte eingebunden, die je nach Be- trachtungsperspektive ebenfalls dem weiten Feld der populären Musik zuzuschlagen sind. Die Tatsache, dass es sich bei den einschlägigen Genre-Kategorien um reine Platzhalterbegriffe handelt, die weder stabile Zu- schreibungen -

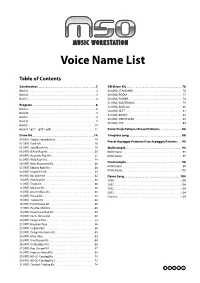

M50 Voice Name List

Voice Name List Table of Contents Combination . .2 GM Drum Kit . 76 Bank A. .2 48 (GM): STANDARD . 76 Bank B. .3 49 (GM): ROOM . 77 Bank C. .4 50 (GM): POWER. 78 51 (GM): ELECTRONIC . 79 Program . .6 52 (GM): ANALOG . 80 Bank A. .6 53 (GM): JAZZ . 81 Bank B. .7 54 (GM): BRUSH . 82 Bank C. .8 55 (GM): ORCHESTRA. 83 Bank D . .9 56 (GM): SFX . 84 Bank E . 10 Bank G / g(1)…g(9) / g(d). 11 Drum Track Patterns/Preset Patterns. 86 Drum Kit . .14 Template song . 88 00 (INT): Studio Standard Kit. 14 Preset Arpeggio Patterns/User Arpeggio Patterns . 90 01 (INT): Funk Kit. 16 02 (INT): Jazz/Brush Kit . 18 Multisample. 94 03 (INT): B.Real Rap Kit . 20 ROM mono . 94 04 (INT): Acoustic Pop Kit. 22 ROM stereo . 97 05 (INT): Wild Rock Kit . 24 Drumsample . 98 06 (INT): New Processed Kit. 26 07 (INT): Electro Rock Kit . 28 ROM mono . 98 08 (INT): Insane FX Kit . 30 ROM stereo . 103 09 (INT): Nu Style Kit . 32 Demo Song. 104 10 (INT): Hip Hop Kit . 34 S000 . 104 11 (INT): Tricki kit. 36 S001 . 104 12 (INT): Mashed Kit. 38 S002 . 104 13 (INT): Drum'n'Bass Kit . 40 S003 . 104 14 (INT): House Kit . 42 Cue List . 104 15 (INT): Trance Kit . 44 16 (INT): Hard House Kit . 46 17 (INT): Psycho-Chill Kit . 48 18 (INT): Down Low Rap Kit. 50 19 (INT): Orch.-Ethnic Kit . 52 20 (INT): Original Perc . 54 21 (INT): Brazilian Perc. 56 22 (INT): Cuban Perc . -

Music Business in Detroit

October 18, 2013 Music Business in Detroit: Estimating the Size of the Music Industry in the Motor City Prepared by: Anderson Economic Group, LLC Colby Spencer Cesaro, Senior Analyst Alex Rosaen, Senior Consultant Lauren Branneman, Senior Analyst Forward by: Patrick L. Anderson, Principal & CEO Anderson Economic Group, LLC 1555 Watertower Place, Suite 100 East Lansing, Michigan 48823 Tel: (517) 333-6984 Fax: (517) 333-7058 www.AndersonEconomicGroup.com © Anderson Economic Group, LLC, 2013 Permission to reproduce in entirety granted with proper citation. All other rights reserved. Foreword I'm pleased to share with readers of Crain's Detroit Business, as well as with others in the Detroit region, this first-of-its-kind study of the business of music in southeast Michigan. Everyone that grew up in this area knows of the "Motown sound," as well as the heritage of jazz, blues, and rock that has steeped into our culture. Many of us are also aware of the more recent innovations of techno and hip-hop, much of which has roots in Detroit. However, until now there has been no systematic analysis of the business of music in our area. Our Anderson Economic Group consultants have combed census and other business records; examined the geographic pattern of nightclubs and perfor- mance venues; scanned demographic patterns for concentrations of heavy enter- tainment consumers; and even conducted primary research into the days/nights of live music available to metro Detroiters at over two hundred specific bars, taverns, and clubs. What we have assembled is a thorough analysis of an indus- try that has always been important to our culture, but can now also be known for its contributions to our employment and earnings. -

Lyricist's Lyrical Lyrics: Widening the Scope of Poetry Studies by Claiming the Obvious

Paper from the Conference “Current Issues in European Cultural Studies”, organised by the Advanced Cultural Studies Institute of Sweden (ACSIS) in Norrköping 15-17 June 2011. Conference Proceedings published by Linköping University Electronic Press: http://www.ep.liu.se/ecp_home/index.en.aspx?issue=062. © The Author. Lyricist’s Lyrical Lyrics: Widening the Scope 1 of Poetry Studies by Claiming the Obvious Geert Buelens Utrecht University/ Stellenbosch University [email protected] Poetry is all but absent from Cultural Studies. Most treatments of the genre tend to focus on canonized poets whose work is wilfully difficult and obscure. Alternative histories should be explored, opening up possibilities to view poetry again as a culturally relevant art form. The demotic and popular strain provides a case in point. From the Romantics onwards modern poetry linked itself with oral or folk traditions like the ballad. Socially the most popular of these forms is the pop lyric. Since the 1950s rock lyrics have been studied in Social Studies, Cultural Studies, Musicology and some English Departments, but rarely within the context of Poetics or Comparative Literature. Rap and canonized singer-songwriters like Dylan and Cohen are the exceptions to the rule. Systematic attention to both lyrics and performance may open up current ideas of what a poem is and how it works. 1 This article is the non copy-edited draft of a paper presented at the 2011 ACSIS conference ‘Current Issues in European Cultural Studies’, Norrköping, 15-17 June 2011 within the session ‘Revisiting the Literary Within Cultural Studies’. 495 LYRICIST’s LYRICAL LYRICS: WIDENING THE SKOPE OF POETRY STUDIES BY CLAIMING THE OBVIOUS Listen – I’m not dissin but there’s something that you’re missin Maybe you should touch reality KRS-One/Boogie Down Productions, ‘Poetry’ (1987) (in Bradley&DuBois 2010, 145) It is a truism of sorts to claim that Cultural Studies tries to understand the world we live in and to explain how cultural artefacts both reflect and construct that world and its inherent political tensions.