Explaining Belgium National Crisis-3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. Foreword by Cleveland Moffett, the Bulletin Magazine the Belgian

2. Foreword by Cleveland Moffett, The Bulletin Magazine The Belgian Revolution of 1830 has never been celebrated with the uproarious firework festivities that the national upheavals of the French, Americans, Mexicans or Russians inspire every year. One reason is that the Belgians never had any such colourful characters as Danton, Washington, Zapata or Lenin. They have their statues of Rogier, Gendebien and Merode, of course, and then there was that riot at the opera house in August – young men stirred by a romantic aria to throw their top hats in the air and cry ‘Liberty!’ – followed by the four days in September of valiant battle and around the Royal Park, all splendid events well worth commemorating. And yet the date chosen as Belgium’s national day is July 21, 1831, when an immigrant German prince agreed to be called Leopold I and to accept the role of the people’s king. Still, it was a peaceful compromise that ended a year of turmoil. A constitutional monarchy was what the upstart new nation’s powerful neighbours insisted upon. The only holdout, the one fierce opponent of this sensible solution, was journalist Louis de Potter (Bruges, 1786-1859). He, strangely enough, has no public statue or acknowledgement for his merits. Nothing more than a blue plate with his name in a short dusty side street in the pink district of Schaerbeek. And yet, without Louis de Potter it is hardly likely that there would have been any revolution at all. It was his eloquence, his pamphlets and proclamations, that led the people of Belgium, then under the thumb of William I of the Netherlands, to believe they could rise up against Dutch tyranny and go it alone. -

D E Staatshervorm

13 Maart 2013 De Staatshervorming Magazine van de Belgische Kamer van volksvertegenwoordigers INHOUD Voorwoord 3 Meer weten over de Kamer? Wat doet de Kamer van volksvertegenwoordigers? 4 Had u altijd al willen weten hoe het er in een parlement aan toe gaat? Hoe Samenstelling van de Kamer 6 een wet tot stand komt? Wat er besproken wordt tijdens de parlementaire vergaderingen? Geen probleem. We zetten de mogelijkheden voor u op De Staatshervorming 8 een rijtje. De Kamer levert in 13 Een rondleiding volgen De nieuwe nationaliteitswet 16 Dagelijks, behalve op zondag, vinden er rondleidingen plaats. Een groeps- bezoek is gratis en duurt anderhalf tot twee uur. Een groep bestaat best uit Europese wetgeving: de nationale parlementen hebben inspraak 18 20 personen. We raden u aan uw bezoek minstens twee maanden vooraf te boeken. We ontvangen immers jaarlijks vele duizenden bezoekers uit De pensioenhervorming 20 binnen- en buitenland. Parlementaire diplomatie: parlementen wisselen ervaring uit 21 Een vergadering bijwonen 11 november 2012 - Herdenking einde Eerste Wereldoorlog 22 De plenaire vergaderingen en de meeste commissievergaderingen zijn openbaar. Iedereen kan ze bijwonen. Vooraf reserveren hoeft niet. U 15 november 2012 - Koningsdag in het Federaal Parlement 23 meldt zich gewoon aan bij het onthaal. Het Paleis der Natie 24 Surf naar www.dekamer.be om te weten welke vergaderingen wanneer plaatsvinden en wat er op de agenda staat. U kan de plenaire vergaderingen ook live volgen op onze website: ga naar ‘Meekijken vergaderingen’. Daar vindt u ook de gearchiveerde beelden van de voorbije vergaderingen. De Kamer volgen op Twitter Via Twitter brengen we geïnteresseerden op de hoogte van de belangrijkste punten op de parlementaire agenda, het resultaat van de stemmingen en andere wetenswaardigheden. -

Sovereignty, Civic Participation, and Constitutional Law: the People Versus the Nation in Belgium

Sovereignty, Civic Participation, and Constitutional Law: The People versus the Nation in Belgium Edited by Brecht Deseure, Raf Geenens, and Stefan Sottiaux First published in 2021 ISBN: 978-0-367-48359-3 (hbk) ISBN: 978-0-367-71228-0 (pbk) ISBN: 978-1-003-03952-5 (ebk) Chapter 15 Sovereignty without sovereignty: The Belgian solution Raf Geenens (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) This OA chapter is funded by KU Leuven. 15 Sovereignty without sovereignty The Belgian solution Raf Geenens “Let us delete the word sovereignty from our vocabulary” Benjamin Constant (1830) At least since 1950, Belgian constitutional law is in the grip of a myth: the myth of national sovereignty.1 Framed as an originalist claim about the meaning of arti- cle 25 at the time of its ratification, scholars and judges alike hold that sovereignty in the Belgian context means ‘national sovereignty’.2 National sovereignty is here understood as the opposite of popular sovereignty, in line with the conceptual dichotomy expounded by, among others, French legal theorist Raymond Carré de Malberg. In recent years, several authors have demonstrated that this inter- pretation of the Constitution is highly anachronistic (De Smaele, 2000; Deseure, 2016; Geenens and Sottiaux, 2015). The Belgian drafters, when working on the Constitution in 1830–1831, did not understand sovereignty in the terms that are now routinely ascribed to them. The national sovereignty myth, it seems, is a product of muddled thinking. In order to stave off the push for more – and more direct – democracy, subsequent generations of legal scholars applied ever thicker conceptual layers to the Constitution, up to the point where it has come to say nearly the opposite of what it said in 1831. -

Heritage Days 15 & 16 Sept

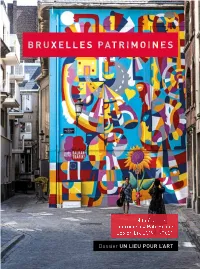

HERITAGE DAYS 15 & 16 SEPT. 2018 HERITAGE IS US! The book market! Halles Saint-Géry will be the venue for a book market organised by the Department of Monuments and Sites of Brussels-Capital Region. On 15 and 16 September, from 10h00 to 19h00, you’ll be able to stock up your library and take advantage of some special “Heritage Days” promotions on many titles! Info Featured pictograms DISCOVER Organisation of Heritage Days in Brussels-Capital Region: Regional Public Service of Brussels/Brussels Urbanism and Heritage Opening hours and dates Department of Monuments and Sites a THE HERITAGE OF BRUSSELS CCN – Rue du Progrès/Vooruitgangsstraat 80 – 1035 Brussels c Place of activity Telephone helpline open on 15 and 16 September from 10h00 to 17h00: Launched in 2011, Bruxelles Patrimoines or starting point 02/204.17.69 – Fax: 02/204.15.22 – www.heritagedays.brussels [email protected] – #jdpomd – Bruxelles Patrimoines – Erfgoed Brussel magazine is aimed at all heritage fans, M Metro lines and stops The times given for buildings are opening and closing times. The organisers whether or not from Brussels, and reserve the right to close doors earlier in case of large crowds in order to finish at the planned time. Specific measures may be taken by those in charge of the sites. T Trams endeavours to showcase the various Smoking is prohibited during tours and the managers of certain sites may also prohibit the taking of photographs. To facilitate entry, you are asked to not B Busses aspects of the monuments and sites in bring rucksacks or large bags. -

Obligation and Self-Interest in the Defence of Belgian Neutrality, 1830-1870

CONTEXTUAL RESEARCH IN LAW CORE VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT BRUSSEL Working Papers No. 2017-2 (August) Permanent Neutrality or Permanent Insecurity? Obligation and Self-Interest in the Defence of Belgian Neutrality, 1830-1870 Frederik Dhondt Please do not cite without prior permission from the author The complete working paper series is available online at http://www.vub.ac.be/CORE/wp Permanent Neutrality or Permanent Insecurity? Obligation and Self-Interest in the Defence of Belgian Neutrality, 1830-1870 Frederik Dhondt1 Introduction ‘we are less complacent than the Swiss, and would not take treaty violations so lightly.’ Baron de Vrière to Sylvain Van de Weyer, Brussels, 28 June 18592 Neutrality is one of the most controversial issues in public international law3 and international relations history.4 Its remoteness from the United Nations system of collective security has rendered its discussion less topical.5 The significance of contemporary self-proclaimed ‘permanent neutrality’ is limited. 6 Recent scholarship has taken up the theme as a general narrative of nineteenth century international relations: between the Congress of Vienna and the Great War, neutrality was the rule, rather than the exception.7 In intellectual history, Belgium’s neutral status is seen as linked to the rise of the ‘Gentle Civilizer of Nations’ at the end of the nineteenth century.8 International lawyers’ and politicians’ activism brought three Noble Peace Prizes (August Beernaert, International Law Institute, Henri La Fontaine). The present contribution focuses on the permanent or compulsory nature of Belgian neutrality in nineteenth century diplomacy, from the country’s inception (1830-1839)9 to the Franco- 1 Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), University of Antwerp, Ghent University/Research Foundation Flanders. -

Redalyc.“Freemasonry As a Patriotic Society? the 1830 Belgian Revolution”

REHMLAC. Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña E-ISSN: 1659-4223 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica Maes, Anaïs “Freemasonry as a Patriotic Society? The 1830 Belgian Revolution” REHMLAC. Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña, vol. 2, núm. 2, -diciembre, 2010, pp. 1-17 Universidad de Costa Rica San José, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=369537359001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative “Freemasonry as a Patriotic Society? The 1830 Belgian Revolution” Anaïs Maes Consejo Científico: José Antonio Ferrer Benimeli (Universidad de Zaragoza), Miguel Guzmán-Stein (Universidad de Costa Rica), Eduardo Torres-Cuevas (Universidad de La Habana), Andreas Önnerfors (University of Leiden), María Eugenia Vázquez Semadeni (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), Roberto Valdés Valle (Universidad Centroamericana “José Simeón Cañas”), Carlos Martínez Moreno (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), Céline Sala (Université de Perpignan) Editor: Yván Pozuelo Andrés (IES Universidad Laboral de Gijón) Director: Ricardo Martínez Esquivel (Universidad de Costa Rica) Dirección web: http://rehmlac.com/main.html Correo electrónico: [email protected] Apartado postal: 243-2300 San José, Costa Rica REHMLAC ISSN 1659-4223 2 Vol. 2, Nº 2, Diciembre 2010-Abril 2011 Fecha de recibido: 12 junio 2010 – Fecha de aceptación: 3 agosto 2010 Palabras clave Masonería, patriotismo, nacionalismo, revolución, Bélgica Keywords Freemasonry, patriotism, nationalism, revolution, Belgium Resumen Al cuestionar la masonería y el patriotismo, tenemos que conceptualizar el análisis de la evolución de la identidad patriótica. -

Demain La Wallonie Avec La France Vers La Réunification Française

Paul-Henry Gendebien Demain la Wallonie avec la France Vers la réunification française Cet ouvrage est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Paternité - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 2.0 Belgique. Editeur responsable : Paul-Henry Gendebien, Jevigné 38 à 4990 Lierneux Illustration de couverture : coq wallon dans l'Hexagone et le drapeau français Texte achevé le 15 décembre 2013 (avant les élections du 25 mai 2014) Remerciements à Joël Goffin pour la relecture et la mise en page Table des matières CHAPITRE PREMIER.........................................................................................1 VERS LE DEMEMBREMENT DE LA BELGIQUE : LA FRANCE INTERPELLEE.................................................................................................1 Un gouvernement assis sur un baril de poudre..............................................4 Inévitable implication de la France...............................................................9 La nécessité et l’honneur.............................................................................10 Légitimité d’une assistance à peuple en danger..........................................16 Donner un objectif ambitieux à une nouvelle génération républicaine.......19 CHAPITRE II......................................................................................................21 COMMENT UNE CONSTRUCTION D’ABORD VOULUE PAR L’EUROPE EST ENSUITE DEVENUE INUTILE........................................21 Menaces contre l’ordre européen issu du -

Dossier UN LIEU POUR L'art

Numéro spécial Journées du Patrimoine Septembre 2019 | N° 031 Dossier UN LIEU POUR L’ART UN LIEU DANS L'ART LA COMMÉMORATION PICTURALE DU DOSSIER CINQUANTENAIRE DE L'INDÉPENDANCE BELGE WERNER ADRIAENSSENS CONSERVATEUR COLLECTIONS XXe SIÈCLE, MUSÉES ROYAUX D'ART ET D'HISTOIRE THOMAS DEPREZ HISTORIEN DE L'ART Détail de la peinture Cinquantième anniversaire de l’indépendance belge par C. Van Camp, 1890, Palais de la Nation (huile sur toile) (© KIK-IRPA, Brussels). Bien qu’à la fin du XIXe siècle, la photographie était déjà parfaitement en mesure de représenter des manifestations de masse, les grandes célébrations étaient encore toujours immortalisées par des artistes peintres. Werner Adriaenssens et Thomas Deprez se sont plongés dans les sources iconographiques de la cérémonie du cinquantième anniversaire de NOTE DE LA RÉDACTION l’indépendance belge et la concurrence que se livrèrent quelques peintres pour s’attirer une commande officielle de l’État pour une représentation monumentale de ce moment hors du commun. Le Palais de la Nation, siège du évoque les célébrations patrio- aménagé pour l’exposition, a attiré Parlement fédéral, abrite une toile tiques du 16 août 1880. À l’époque, les foules en ce jour d’été, dans une monumentale, le Cinquantième une exposition nationale a été orga- chaleur torride. Van Camp s’en est anniversaire de l’indépendance nisée pour fêter les 50 ans de l’in- servi comme décor pour immorta- belge, que nous devons au peintre dépendance de la Belgique. Le parc liser la fête. Camille Van Camp (fig. 1). L’œuvre du Cinquantenaire, spécialement Un lieu pour l’Art N°031 - NUMÉRO SPÉCIAL - SEPTEMBRE 2019 SEPTEMBRE - SPÉCIAL NUMÉRO - N°031 Fig. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

PATHS TO SUCCESS, PATHS TO FAILURE: HISTORICAL TRAJECTORIES TO DEMOCRATIC STABILITY By ADAM BILINSKI A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2015 1 © 2015 Adam Bilinski 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Throughout the work on this project, I received enormous help from a number of people. The indispensable assistance was provided by my advisor Michael Bernhard, who encouraged me to work on the project since I arrived at the University of Florida. He gave me valuable and timely feedback, and his wide knowledge of the European political history and research methods proved irreplaceable in this regard. He is otherwise a warm, humble and an understanding person, a scholar who does not mind and even appreciates when a graduate student is critical toward his own ideas, which is a feature whose value cannot be overestimated. I received also valuable assistance from members of my dissertation committee: Benjamin Smith, Leonardo A. Villalon, Beth Rosenson and Chris Gibson. In particular, Ben Smith taught me in an accessible way about the foundational works in Political Science, which served as an inspiration to write this dissertation, while Chris Gibson offered very useful feedback on quantitative research methods. In addition, I received enormous help from two scholars at the University of Chicago, where this research project passed through an adolescent stage. Dan Slater, my advisor, and Alberto Simpser helped me transform my incoherent hypotheses developed in Poland into a readable master’s thesis, which I completed in 2007. -

Was Basic Income Invented in Belgium in 1848? Exploring the Origins and Continuing Relevance of a Simple Idea

Was Basic Income Invented in Belgium in 1848? Exploring the Origins and Continuing Relevance of a Simple Idea Guido Erreygers and John Cunliffe April 2018 Abstract Basic income proposals have a long and interesting history. Two of the earliest, and nearly forgotten, proposals were formulated in Brussels in 1848. One was short, anonymous and written in Dutch; the other long, authored and written in French. As far as we can tell, the two proposals are unrelated: they originated in different circles. In this paper we explore the roots of each proposal, and try to explain why Brussels proved to be a fertile ground for basic income ideas in 1848. In addition, we show that there are striking similarities between these old proposals and the present-day debate on basic income. The similarities refer both to the diagnosis of the problems to be addressed and to the difficulties which have been thought to beset the proposals. Acknowledgements This paper is to a large extent based on our previous joint work on the history of basic income proposals. We thank Walter Van Trier for many stimulating discussions and Philippe Van Parijs for encouraging us to explore the history of basic income. Maryline Van Parijs has been helpful in collecting genealogical information. The paper was prepared for the HES Sponsored Session “Basic Income: The Past and the Present”, ASSA Annual Meeting 2018, 5-7 January 2018 (Philadelphia, USA), and has also been presented at the Toon Vandevelde Colloquium, 12-13 January 2018 (University of Louvain, Belgium). All errors are our responsibility. Address of the authors: Guido Erreygers, Department of Economics, University of Antwerp, Belgium & Centre for Health Policy, University of Melbourne, Australia: [email protected]; John Cunliffe: [email protected]. -

National Sovereignty in the Belgian Constitution of 1831. on the Meaning(S) of Article 25

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Springer - Publisher Connector National Sovereignty in the Belgian Constitution of 1831. On the Meaning(s) of Article 25 Brecht Deseure Abstract Article 25 of the Belgian Constitution of 1831 specifi es that all powers emanate from the nation, but fails to defi ne who or what the nation is. This chapter aims at reconstructing the underdetermined meaning of national sovereignty by looking into a wide array of sources concerning the genesis and reception of the Belgian Constitution. It argues, fi rstly, that ‘nation’ and ‘King’ were conceptually differentiated notions, revealing a concern on the part of the Belgian National Congress to substitute the popular principle for the monarchical one. By vesting the origin of sovereignty exclusively in the nation, it relegated the monarch to the posi- tion of a constituted power. Secondly, it refutes the widely accepted defi nition of national sovereignty as the counterpart of popular sovereignty. The debates of the constituent assembly prove that the antithesis between the concepts ‘nation’ and ‘people’, supposedly originating in two rivalling political-theoretical traditions, is a false one. Not only were both terms used as synonyms, the Congress delegates themselves plainly proclaimed the sovereignty of the people. However, this did not imply the establishment of universal suffrage, since political participation was lim- ited to the propertied classes. The revolutionary press generally endorsed the popu- lar principle, too, without necessarily agreeing to the form it was given in practice. The legitimacy of the National Congress’s claim to speak in the name of the people was challenged both by the conservative press, which rejected the sovereignty of the people, and by the radical newspapers, which considered popular sovereignty inval- idated by the instatement of census suffrage. -

Les Fondateurs

PAUL HYMANS 1830 LES FONDATEURS Conférence à rUniversité des Annales, à Bruxelles (27 Mars 1914) "Bruxelles Éditions de la Belgique Artistique et Littéraire 26, Hue des Minimes 1830 - LES FONDATEURS CONFÉRENCE DE M. PAUL HYMANS A L'UNIVERSITÉ DES ANNALES, A BRUXELLES (27 MARS 1914) Mesdames, Messieurs, Par une exception dont le Comité des Annales a fait une règle annuelle, cette dernière conférence de l'hiver est une conférence belge. Comment ne serais-je pas flatté de l'honneur qui m'est dévolu d'occuper aujourd'hui cette tribune? Comment aussi, succédant à tant d'orateurs experts en l'art de vous instrure avec agrément, ne sentigais-je pas ma fai• blesse? D'autant que je n'ai point la ressource. Mesdames, pour me concilier votre faveur, de débuter par ce com• pliment traditionnel, et d'un succès assuré, qui est de vous proclamer égales aux plus brillantes Parisiennes. Et puis il n'y aura ni récitations, ni chants, ni pro• jections. Et enfin ce conférencier belge aura la singulière audace d'entretenir ce public belge d'un sujet belge, de choses de ce pays, empruntées à son passé, à «on passé rela• tivement récent. 1830, quelques aspects de l'époque, un profil en rac• courci des événements, quelques figures qui y furent mê• lées, en somme un peu d'histoire avec des illustrations verbales, telle sera la substance de cette causerie que je voudrais familière, sans apprêts d'éloquence, et je l'espère sans pédantisme. 2 LES FONDATEURS I 1830, combien c'est à la fois près et loin de nous.