The NAACP and the Implementation of Brown V. Board of Education in Virginia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The "Virginian-Pilot" Newspaper's Role in Moderating Norfolk, Virginia's 1958 School Desegregation Crisis

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations in Urban Services - College of Education & Professional Studies Urban Education (Darden) Winter 1991 The "Virginian-Pilot" Newspaper's Role in Moderating Norfolk, Virginia's 1958 School Desegregation Crisis Alexander Stewart Leidholdt Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/urbanservices_education_etds Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Education Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Leidholdt, Alexander S.. "The "Virginian-Pilot" Newspaper's Role in Moderating Norfolk, Virginia's 1958 School Desegregation Crisis" (1991). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), dissertation, , Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/tb1v-f795 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/urbanservices_education_etds/119 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Education & Professional Studies (Darden) at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations in Urban Services - Urban Education by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 THE VIRGINIAN-PILOT NEWSPAPER'S ROLE IN MODERATING NORFOLK, VIRGINIA'S 1958 SCHOOL DESEGREGATION CRISIS by Alexander Stewart Leidholdt B.A. May 1978, Virginia Wesleyan College M.S. May 1980, Clarion University Ed.S. December 1984, Indiana University A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion Unversity in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY URBAN SERVICES OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY December, 1991 Approved By: Maurice R. Berube, Dissertation Chair Concentration Area^TFlrector ember Dean of the College of Education Member Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

William F. Winter and the Politics of Racial Moderation in Mississippi

WILLIAM WINTER AND THE POLITICS OF RACIAL MODERATION 335 William F. Winter and the Politics of Racial Moderation in Mississippi by Charles C. Bolton On May 12, 2008, William F. Winter received the Profile in Courage Award from the John F. Kennedy Foundation, which honored the former Mississippi governor for “championing public education and racial equality.” The award was certainly well deserved and highlighted two important legacies of one of Mississippi’s most important public servants in the post–World War II era. During Senator Edward M. Kennedy’s presentation of the award, he noted that Winter had been criticized “for his integrationist stances” that led to his defeat in the gubernatorial campaign of 1967. Although Winter’s opponents that year certainly tried to paint him as a moderate (or worse yet, a liberal) and as less than a true believer in racial segregation, he would be the first to admit that he did not advocate racial integration in 1967; indeed, much to his regret later, Winter actually pandered to white segregationists in a vain attempt to win the election. Because Winter, over the course of his long career, has increasingly become identified as a champion of racial justice, it is easy, as Senator Kennedy’s remarks illustrate, to flatten the complexity of Winter’s evolution on the issue CHARLES C. BOLTON is the guest editor of this special edition of the Journal of Mississippi History focusing on the career of William F. Winter. He is profes- sor and head of the history department at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

![Miranda, 5 | 2011, « South and Race / Staging Mobility in the United States » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Décembre 2011, Consulté Le 16 Février 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8829/miranda-5-2011-%C2%AB-south-and-race-staging-mobility-in-the-united-states-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-01-d%C3%A9cembre-2011-consult%C3%A9-le-16-f%C3%A9vrier-2021-138829.webp)

Miranda, 5 | 2011, « South and Race / Staging Mobility in the United States » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Décembre 2011, Consulté Le 16 Février 2021

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 5 | 2011 South and Race / Staging Mobility in the United States Sud et race / Mise en scène et mobilité aux États-Unis Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/83 DOI : 10.4000/miranda.83 ISSN : 2108-6559 Éditeur Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Référence électronique Miranda, 5 | 2011, « South and Race / Staging Mobility in the United States » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 décembre 2011, consulté le 16 février 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/83 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.83 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 16 février 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. 1 SOMMAIRE South and Race Introduction Anne Stefani Forgetting the South and the Southern Strategy Michelle Brattain Image, Discourse, Facts: Southern White Women in the Fight for Desegregation, 1954-1965 Anne Stefani Re-Writing Race in Early American New Orleans Nathalie Dessens Integrating the Narrative: Ellen Douglas's Can't Quit You Baby and the Sub-Genre of the Kitchen Drama Jacques Pothier Representing the Dark Other: Walker Percy's Shadowy Figure in Lancelot Gérald Preher Burning Mississippi: Race, Fatherhood and the South in A Time to Kill (1996) Hélène Charlery Laughing at the United States Eve Bantman-Masum Staging American Mobility Introduction Emeline Jouve Acte I. La Route de l'ouest : Politique(s) des représentations / Act I. The Way West: Representations and Politics The Road West, Revised Editions Audrey Goodman Le héros de la Frontière, un mythe de la fondation en mouvement Daniel Agacinski Acte II. -

Movement 1954-1968

CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT 1954-1968 Tuesday, November 27, 12 NEW MEXICO OFFICE OF AFRICAN AMERICAN AFFAIRS Curated by Ben Hazard Tuesday, November 27, 12 Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, The initial phase of the black protest activity in the post-Brown period began on December 1, 1955. Rosa Parks of Montgomery, Alabama, refused to give up her seat to a white bus rider, thereby defying a southern custom that required blacks to give seats toward the front of buses to whites. When she was jailed, a black community boycott of the city's buses began. The boycott lasted more than a year, demonstrating the unity and determination of black residents and inspiring blacks elsewhere. Martin Luther King, Jr., who emerged as the boycott movement's most effective leader, possessed unique conciliatory and oratorical skills. He understood the larger significance of the boycott and quickly realized that the nonviolent tactics used by the Indian nationalist Mahatma Gandhi could be used by southern blacks. "I had come to see early that the Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available to the Negro in his struggle for freedom," he explained. Although Parks and King were members of the NAACP, the Montgomery movement led to the creation in 1957 of a new regional organization, the clergy-led Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) with King as its president. King remained the major spokesperson for black aspirations, but, as in Montgomery, little-known individuals initiated most subsequent black movements. On February 1, 1960, four freshmen at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College began a wave of student sit-ins designed to end segregation at southern lunch counters. -

Black Women As Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools During the 1950S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Hostos Community College 2019 Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools during the 1950s Kristopher B. Burrell CUNY Hostos Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ho_pubs/93 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] £,\.PYoo~ ~ L ~oto' l'l CILOM ~t~ ~~:t '!Nll\O lit.ti t~ THESTRANGE CAREERS OfTHE JIMCROW NORTH Segregation and Struggle outside of the South EDITEDBY Brian Purnell ANOJeanne Theoharis, WITHKomozi Woodard CONTENTS '• ~I') Introduction. Histories of Racism and Resistance, Seen and Unseen: How and Why to Think about the Jim Crow North 1 Brian Purnelland Jeanne Theoharis 1. A Murder in Central Park: Racial Violence and the Crime NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS Wave in New York during the 1930s and 1940s ~ 43 New York www.nyupress.org Shannon King © 2019 by New York University 2. In the "Fabled Land of Make-Believe": Charlotta Bass and All rights reserved Jim Crow Los Angeles 67 References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or John S. Portlock changed since the manuscript was prepared. 3. Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in Names: Purnell, Brian, 1978- editor. -

Final Report and Working Papers of the Twenty-Second Seminar On

H. , . BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY PROVO. UTAH 8S 12- 11 THE MULTIFACETED ROLE OF THE LATIN AMERICAN SUBJECT SPECIALIST Final Report and Working Papers of the Twenty -second Seminar on the Acquisition of Latin American Library Materials University of Florida Gainesville, Florida June 12-17, 1977 Anne H. Jordan Editor SALALM Secretariat Austin, Texas 1979 Copyright Q by SALAIM Inc. 1979 HAROLD B. LEE LIBRARY BRIGHAM YOUNG UK SITY PROvn iitau — — iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vii PROGRAM AND RESOLUTIONS Program and Schedule of Activities 3 Resolutions 8 SUMMARY REPORTS OF THE SESSIONS Latin American Area Centers and Library Research Resources: A Challenge for Survival—Laurence Hallewell 13 User Education Programs : The Texas Experience —Mary Ferris Burns . 17 Archives and Data Banks —Richard Puhek 19 Politics and Publishing: The Cases of Argentina, Brazil, and Chile—Sammy Alzofon Kinard 20 The Latin American Specialist and the Collection: In-House Bibliography Models for a Guide to the Resources on Latin America in the Library—Dan C. Hazen 22 Problems in the Acquisition of Central American and Caribbean Material—Lesbia Varona U2 The Latin American Subject Specialist and Reference Service Karen A. Schmidt **3 Final General Session—Mina Jane Grothey 51 ANNUAL REPORTS TO SALALM A Bibliography of Latin American Bibliographies Daniel Raposo Cordeiro 59 Microfilming Projects Newsletter No. 19—Suzanne Hodgman 9o Report of the Bibliographical Activities of the Latin American, Portuguese and Spanish Division—Mary Ellis Kahler 108 Latin American Books: Average Costs for Fiscal Years 1973, 197 1*, 1975, and 1976—Robert C. Sullivan Ill Latin American Activities in the United Kingdom Laurence Hallewell 11^ — — — —— 1V Page Resources for Latin American Studies in Australia—National Library of Australia 119 Library Activities in the Caribbean Area 1976/77: Report to SALALM XXII—Alma T. -

Unwise and Untimely? (Publication of "Letter from a Birmingham Jail"), 1963

,, te!\1 ~~\\ ~ '"'l r'' ') • A Letter from Eight Alabama Clergymen ~ to Martin Luther J(ing Jr. and his reply to them on order and common sense, the law and ~.. · .. ,..., .. nonviolence • The following is the public statement directed to Martin My dear Fellow Clergymen, Luther King, Jr., by eight Alabama clergymen. While confined h ere in the Birmingham City Jail, I "We the ~ders igned clergymen are among those who, in January, 1ssued 'An Appeal for Law and Order and Com· came across your r ecent statement calling our present mon !)ense,' in dealing with racial problems in Alabama. activities "unwise and untimely." Seldom, if ever, do We expressed understanding that honest convictions in I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas. If racial matters could properly be pursued in the courts I sought to answer all of the criticisms that cross my but urged that decisions ot those courts should in the mean~ desk, my secretaries would he engaged in little else in time be peacefully obeyed. the course of the day, and I would have no time for "Since that time there had been some evidence of in constructive work. But since I feel that you are men of creased forbearance and a willingness to face facts. Re genuine goodwill and your criticisms are sincerely set sponsible citizens have undertaken to work on various forth, I would like to answer your statement in what problems which cause racial friction and unrest. In Bir I hope will he patient and reasonable terms. mingham, recent public events have given indication that we all have opportunity for a new constructive and real I think I should give the reason for my being in Bir· istic approach to racial problems. -

African-American Parents' Experiences in a Predominantly White School

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE June 2017 Opportunity, but at what cost? African-American parents' experiences in a predominantly white school Peter Smith Smith Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Peter Smith, "Opportunity, but at what cost? African-American parents' experiences in a predominantly white school" (2017). Dissertations - ALL. 667. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/667 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract National measures of student achievement, such as the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), provide evidence of the gap in success between African- American and white students. Despite national calls for increased school accountability and focus on achievement gaps, many African-American children continue to struggle in school academically, as compared to their white peers. Ladson-Billings (2006) argues that a deeper understanding of the legacy of disparity in funding for schools serving primarily African- American students, shutting out African-American parents from civic participation, and unfair treatment of African-Americans despite their contributions to the United States is necessary to complicate the discourse about African-American student performance. The deficit model that uses student snapshots of achievement such as the NAEP and other national assessments to explain the achievement gap suggests that there is something wrong with African-American children. As Cowen Pitre (2104) explains, however, “the deficit model theory blames the victim without acknowledging the unequal educational and social structures that deny African- American students access to a quality education (2014, pg. -

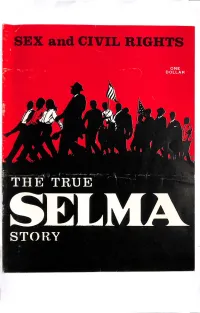

Martin Luther King and Communism Page 20 the Complete Files of a Communist Front Organization Were Taken in a Raid in New Orleans

Several hundred demonstrators were forced to stand on Dexter Ave1me in front of the State Capitol at Montgomery. On the night of March 10, 1965, these demonstrators, who knew that once they left the area they would not be able to return, urinated en masse in the street on the signal of James Forman, SNCC ExecJJtiVe Director. "All right," Forman shoute<)l, "Everyone stand up and relieve yourself." Almost everyone did. Some arrests were made of men who went to obscene extremes in expos ing themselves to local police officers. The True SELMA Story Albert C. (Buck) Persons has lived in Birmingham, Alabama for 15 years. As a stringer for LIFE and managing editor of a metropolitan weekly newspaper he covered the Birmingham demonstrations in 1963. On a special assignment for Con gressman William L. Dickinson of Ala bama he investigated the Selma-Mont gomery demonstrations in March, 1965. In 1961 Persons was one of a handful of pilots hired to support the invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. His story on this two years later led to the admission by President Kennedy that four Ameri can flyers had died in combat over the beaches of Southern Cuba in an effort to drive Fidel Castro from the armed Soviet garrison that had been set up 90 miles off the coast of the United States. After interviewing scores of people who were eye-witnesses to the Selma-Montgomery march, Mr. Persons has written the articles published here. In summation he says, "The greatest obstacle in the Negro's search for "freedom" is the Negro himself and the leaders he has chosen to follow. -

Nominees and Bios

Nominees for the Virginia Emancipation Memorial Pre‐Emancipation Period 1. Emanuel Driggus, fl. 1645–1685 Northampton Co. Enslaved man who secured his freedom and that of his family members Derived from DVB entry: http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.asp?b=Driggus_Emanuel Emanuel Driggus (fl. 1645–1685), an enslaved man who secured freedom for himself and several members of his family exemplified the possibilities and the limitations that free blacks encountered in seventeenth‐century Virginia. His name appears in the records of Northampton County between 1645 and 1685. He might have been the Emanuel mentioned in 1640 as a runaway. The date and place of his birth are not known, nor are the date and circumstances of his arrival in Virginia. His name, possibly a corruption of a Portuguese surname occasionally spelled Rodriggus or Roddriggues, suggests that he was either from Africa (perhaps Angola) or from one of the Caribbean islands served by Portuguese slave traders. His first name was also sometimes spelled Manuell. Driggus's Iberian name and the aptitude that he displayed maneuvering within the Virginia legal system suggest that he grew up in the ebb and flow of people, goods, and cultures around the Atlantic littoral and that he learned to navigate to his own advantage. 2. James Lafayette, ca. 1748–1830 New Kent County Revolutionary War spy emancipated by the House of Delegates Derived from DVB/ EV entry: http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Lafayette_James_ca_1748‐1830 James Lafayette was a spy during the American Revolution (1775–1783). Born a slave about 1748, he was a body servant for his owner, William Armistead, of New Kent County, in the spring of 1781. -

1 After Slavery & Reconstruction: the Black Struggle in the U.S. for Freedom, Equality, and Self-Realization* —A Bibliogr

After Slavery & Reconstruction: The Black Struggle in the U.S. for Freedom, Equality, and Self-Realization* —A Bibliography Patrick S. O’Donnell (2020) Jacob Lawrence, Library, 1966 Apologia— Several exceptions notwithstanding (e.g., some titles treating the Reconstruction Era), this bibliography begins, roughly, with the twentieth century. I have not attempted to comprehensively cover works of nonfiction or the arts generally but, once more, I have made— and this time, a fair number of—exceptions by way of providing a taste of the requisite material. So, apart from the constraints of most of my other bibliographies: books, in English, these particular constraints are intended to keep the bibliography to a fairly modest length (around one hundred pages). This compilation is far from exhaustive, although it endeavors to be representative of the available literature, whatever the influence of my idiosyncratic beliefs and 1 preferences. I trust the diligent researcher will find titles on particular topics or subject areas by browsing carefully through the list. I welcome notice of titles by way of remedying any deficiencies. Finally, I have a separate bibliography on slavery, although its scope is well beyond U.S. history. * Or, if you prefer, “self-fulfillment and human flourishing (eudaimonia).” I’m not here interested in the question of philosophical and psychological differences between these concepts (i.e., self- realization and eudaimonia) and the existing and possible conceptions thereof, but more simply and broadly in their indispensable significance in reference to human nature and the pivotal metaphysical and moral purposes they serve in our critical and evaluative exercises (e.g., and after Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum, in employing criteria derived from the notion of ‘human capabilities and functionings’) as part of our individual and collective historical quest for “the Good.” However, I might note that all of these concepts assume a capacity for self- determination. -

PAPERS of the NAACP Part Segregation and Discrimination, 15 Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier PAPERS OF THE NAACP Part Segregation and Discrimination, 15 Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955 Series B: Administrative Files UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA PAPERS OF THE NAACP Part 15. Segregation and Discrimination, Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955 Series B: Administrative Files A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier PAPERS OF THE NAACP Part 15. Segregation and Discrimination, Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955 Series B: Administrative Files Edited by John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier Project Coordinator Randolph Boehm Guide compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway * Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloglng-ln-Publication Data National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Papers of the NAACP. [microform] Accompanied by printed reel guides. Contents: pt. 1. Meetings of the Board of Directors, records of annual conferences, major speeches, and special reports, 1909-1950 / editorial adviser, August Meier; edited by Mark Fox--pt. 2. Personal correspondence of selected NAACP officials, 1919-1939 / editorial--[etc.]--pt. 15. Segregation and discrimination, complaints and responses, 1940-1955. 1. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People-Archives. 2. Afro-Americans--Civil Rights--History--20th century-Sources. 3. Afro- Americans--History--1877-1964--Sources. 4. United States--Race relations-Sources. I. Meier, August, 1923- .