Mary Mason Williams, "The Civil War Centennial and Public Memory In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The "Virginian-Pilot" Newspaper's Role in Moderating Norfolk, Virginia's 1958 School Desegregation Crisis

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations in Urban Services - College of Education & Professional Studies Urban Education (Darden) Winter 1991 The "Virginian-Pilot" Newspaper's Role in Moderating Norfolk, Virginia's 1958 School Desegregation Crisis Alexander Stewart Leidholdt Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/urbanservices_education_etds Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Education Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Leidholdt, Alexander S.. "The "Virginian-Pilot" Newspaper's Role in Moderating Norfolk, Virginia's 1958 School Desegregation Crisis" (1991). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), dissertation, , Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/tb1v-f795 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/urbanservices_education_etds/119 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Education & Professional Studies (Darden) at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations in Urban Services - Urban Education by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 THE VIRGINIAN-PILOT NEWSPAPER'S ROLE IN MODERATING NORFOLK, VIRGINIA'S 1958 SCHOOL DESEGREGATION CRISIS by Alexander Stewart Leidholdt B.A. May 1978, Virginia Wesleyan College M.S. May 1980, Clarion University Ed.S. December 1984, Indiana University A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion Unversity in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY URBAN SERVICES OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY December, 1991 Approved By: Maurice R. Berube, Dissertation Chair Concentration Area^TFlrector ember Dean of the College of Education Member Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

George Allen?

George Allen's 1~ 000 Days Have Changed Virginia .......................... By Frank B. Atkinson .......................... Mr. Atkinson served in Governor George ALIens economy and society, the fall ofrigid and divisive cabinet as Counselor to the Governor and Direc racial codes, the emergence of the federallevia tor ofPolicy untilSeptembe0 when he returned to than and modern social welfare state, the rise of his lawpractice in Richmond. He is the author of the Cold War defense establishment, the politi "The Dynamic Dominion) )) a recent book about cal ascendancy of suburbia, and the advent of Virginia Politics. competitive two-party politics. Virginia's chief executives typically have not championed change. Historians usually 1keeping with tradition, the portraits ofthe identify only two major reform governors dur sixteen most recent Virginia governors adorn ing this century. Harry Byrd (1926-30) the walls out ide the offices of the current gov reorganized state government and re tructured ernor, George Allen, in Richmond. It is a short the state-local tax system, promoted "pay-as stroll around the third-floor balcony that over you-go" road construction, and pushed through looks the Capitol rotunda, but as one moves a constitutional limit on bonded indebtedne . past the likenesses of Virginia chief executives And Mills Godwin (1966-70,1974-78) imposed spanning from Governor Harry F. Byrd to L. a statewide sales tax, created the community Douglas Wilder, history casts a long shadow. college system, and committed significant new The Virginia saga from Byrd to Wilder is a public resources to education, mental health, Frank B. Atkinson story of profound social and economic change. -

Massive Resistance and the Origins of the Virginia Technical College System

Inquiry: The Journal of the Virginia Community Colleges Volume 22 | Issue 2 Article 6 10-10-2019 Massive Resistance and the Origins of the Virginia Technical College System Richard A. Hodges Ed.D., Thomas Nelson Community College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.vccs.edu/inquiry Part of the Higher Education Commons, History Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Hodges, R. A. (2019). Massive Resistance and the Origins of the Virginia Technical College System. Inquiry: The Journal of the Virginia Community Colleges, 22 (2). Retrieved from https://commons.vccs.edu/inquiry/vol22/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ VCCS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inquiry: The ourJ nal of the Virginia Community Colleges by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ VCCS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hodges: Massive Resistance and the Origins of the VTCS MASSIVE RESISTANCE AND THE ORIGINS OF THE VIRGINIA TECHNICAL COLLEGE SYSTEM RICHARD A. HODGES INTRODUCTION In the summer of 1964, Dr. Dana B. Hamel, Director of the Roanoke Technical Institute in Roanoke, Virginia received a phone call that would change the course of Virginia higher education. The call was from Virginia Governor Albertis Harrison requesting Hamel serve as the Director of the soon to be established Department of Technical Education. The department, along with its governing board, would quickly establish a system of technical colleges located regionally throughout Virginia, with the first of those colleges opening their doors for classes in the fall of 1965. -

Bill Bolling Contemporary Virginia Politics

6/29/21 A DISCUSSION OF CONTEM PORARY VIRGINIA POLITICS —FROM BLUE TO RED AND BACK AGAIN” - THE RISE AND FALL OF THE GOP IN VIRGINIA 1 For the first 200 years of Virginia's existence, state politics was dominated by the Democratic Party ◦ From 1791-1970 there were: Decades Of ◦ 50 Democrats who served as Governor (including Democratic-Republicans) Democratic ◦ 9 Republicans who served as Governor Dominance (including Federalists and Whigs) ◦ During this same period: ◦ 35 Democrats represented Virginia in the United States Senate ◦ 3 Republicans represented Virginia in the United States Senate 2 1 6/29/21 ◦ Likewise, this first Republican majority in the Virginia General Democratic Assembly did not occur until Dominance – 1998. General ◦ Democrats had controlled the Assembly General Assembly every year before that time. 3 ◦ These were not your “modern” Democrats ◦ They were a very conservative group of Democrats in the southern tradition What Was A ◦ A great deal of their focus was on fiscal Democrat? conservativism – Pay As You Go ◦ They were also the ones who advocated for Jim Crow and Massive resistance up until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of in 1965 4 2 6/29/21 Byrd Democrats ◦ These were the followers of Senator Harry F. Byrd, a former Virginia Governor and U.S. Senator ◦ Senator Byrd’s “Byrd Machine” dominated and controlled Virginia politics for this entire period 5 ◦ Virginia didn‘t really become a competitive two-party state until Ơͥ ͣ ǝ, and the first real From Blue To competition emerged at the statewide level Red œ -

Virginia's Massive Folly

Undergraduate Research Journal at UCCS Volume 2.1, Spring 2009 Virginia’s “Massive Folly”: Harry Byrd, Prince Edward County, and the Front Line Laura Grant Dept. of History, University of Colorado at Colorado Springs Abstract This paper examines the closure of public schools in Prince Edward County, Virginia from 1959- 1964 in an effort to avoid desegregation. Specifically, the paper traces the roots of the political actions which led to the closure and then-Governor Harry Byrd's role in Virginia's political machine at the time. The paper argues that it was Byrd's influence which led to the conditions that not only made the closure possible in Virginia, but encouraged the white citizens of Prince Edward County to make their stand. In September, 1959, the public schools in Prince Edward County, Virginia closed their doors to all students. While most white students were educated in makeshift private schools, the doors of public education remained closed until the Supreme Court ordered the schools to reopen in 1964. This drastic episode in Virginia’s history was a response to the public school integration mandated by the Brown vs. Board of Education decision in 1954. Prince Edward County was not the only district in Virginia to take this action; it was merely the most extreme case of resistance after state laws banning integration were struck down as unconstitutional. Schools all over the state closed, most only temporarily, and the white community rallied to offer white students assistance to attend segregated private schools rather than face integration in a movement termed “Massive Resistance.” While this “Brown backlash” occurred all over the South, it was most prevalent in the Deep South. -

A History of the Virginia Democratic Party, 1965-2015

A History of the Virginia Democratic Party, 1965-2015 A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation “with Honors Distinction in History” in the undergraduate colleges at The Ohio State University by Margaret Echols The Ohio State University May 2015 Project Advisor: Professor David L. Stebenne, Department of History 2 3 Table of Contents I. Introduction II. Mills Godwin, Linwood Holton, and the Rise of Two-Party Competition, 1965-1981 III. Democratic Resurgence in the Reagan Era, 1981-1993 IV. A Return to the Right, 1993-2001 V. Warner, Kaine, Bipartisanship, and Progressive Politics, 2001-2015 VI. Conclusions 4 I. Introduction Of all the American states, Virginia can lay claim to the most thorough control by an oligarchy. Political power has been closely held by a small group of leaders who, themselves and their predecessors, have subverted democratic institutions and deprived most Virginians of a voice in their government. The Commonwealth possesses the characteristics more akin to those of England at about the time of the Reform Bill of 1832 than to those of any other state of the present-day South. It is a political museum piece. Yet the little oligarchy that rules Virginia demonstrates a sense of honor, an aversion to open venality, a degree of sensitivity to public opinion, a concern for efficiency in administration, and, so long as it does not cost much, a feeling of social responsibility. - Southern Politics in State and Nation, V. O. Key, Jr., 19491 Thus did V. O. Key, Jr. so famously describe Virginia’s political landscape in 1949 in his revolutionary book Southern Politics in State and Nation. -

The Evelyn T. Butts Story Kenneth Cooper Alexa

Developing and Sustaining Political Citizenship for Poor and Marginalized People: The Evelyn T. Butts Story Kenneth Cooper Alexander ORCID Scholar ID# 0000-0001-5601-9497 A Dissertation Submitted to the PhD in Leadership and Change Program of Antioch University in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2019 This dissertation has been approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in Leadership and Change, Graduate School of Leadership and Change, Antioch University. Dissertation Committee • Dr. Philomena Essed, Committee Chair • Dr. Elizabeth L. Holloway, Committee Member • Dr. Tommy L. Bogger, Committee Member Copyright 2019 Kenneth Cooper Alexander All rights reserved Acknowledgements When I embarked on my doctoral work at Antioch University’s Graduate School of Leadership and Change in 2015, I knew I would eventually share the fruits of my studies with my hometown of Norfolk, Virginia, which has given so much to me. I did not know at the time, though, how much the history of Norfolk would help me choose my dissertation topic, sharpen my insights about what my forebears endured, and strengthen my resolve to pass these lessons forward to future generations. Delving into the life and activism of voting-rights champion Evelyn T. Butts was challenging, stimulating, and rewarding; yet my journey was never a lonely one. Throughout my quest, I was blessed with the support, patience, and enduring love of my wife, Donna, and our two sons, Kenneth II and David, young men who will soon begin their own pursuits in higher education. Their embrace of my studies constantly reminded me of how important family and community have been throughout my life. -

The First Labor History of the College of William and Mary

1 Integration at Work: The First Labor History of The College of William and Mary Williamsburg has always been a quietly conservative town. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century to the time of the Civil Rights Act, change happened slowly. Opportunities for African American residents had changed little after the Civil War. The black community was largely regulated to separate schools, segregated residential districts, and menial labor and unskilled jobs in town. Even as the town experienced economic success following the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg in the early 1930s, African Americans did not receive a proportional share of that prosperity. As the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation bought up land in the center of town, the displaced community dispersed to racially segregated neighborhoods. Black residents were relegated to the physical and figurative margins of the town. More than ever, there was a social disconnect between the city, the African American community, and Williamsburg institutions including Colonial Williamsburg and the College of William and Mary. As one of the town’s largest employers, the College of William and Mary served both to create and reinforce this divide. While many African Americans found employment at the College, supervisory roles were without exception held by white workers, a trend that continued into the 1970s. While reinforcing notions of servility in its hiring practices, the College generally embodied traditional southern racial boundaries in its admissions policy as well. As in Williamsburg, change at the College was a gradual and halting process. This resistance to change was characteristic of southern ideology of the time, but the gentle paternalism of Virginians in particular shaped the College’s actions. -

Political Factors Affecting the Establishment and Growth of Richard Bland College of the College of William and Mary in Virginia 1958-1972

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1981 Political factors affecting the establishment and growth of Richard Bland College of the College of William and Mary in Virginia 1958-1972 James B. McNeer College of William & Mary - School of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation McNeer, James B., "Political factors affecting the establishment and growth of Richard Bland College of the College of William and Mary in Virginia 1958-1972" (1981). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539618656. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.25774/w4-k8e1-wf63 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. -

EOB #392: December 18, 1972-January 1, 1973 [Complete

-1- NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM Tape Subject Log (rev. Aug.-08) Conversation No. 392-1 Date: December 18, 1972 Time: Unknown between 4:13 pm and 5:50 pm Location: Executive Office Building The President met with H. R. (“Bob”) Haldeman and John D. Ehrlichman. [This recording began while the meeting was in progress.] Press relations -Ronald L. Ziegler’s briefings -Mistakes -Henry A. Kissinger -Herbert G. Klein -Kissinger’s briefings -Preparation -Ziegler -Memoranda -Points -Ziegler’s briefing -Vietnam negotiations -Saigon and Hanoi -Prolonging talks and war -Kissinger’s briefing Second term reorganization -Julie Nixon Eisenhower Press relations -Unknown woman reporter -Life -Conversation with Ziegler [?] -Washington Post -Interviews -Helen Smith -Washington Post -2- NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM Tape Subject Log (rev. Aug.-08) Conversation No 392-1 (cont’d) -The President’s conversation with Julie Nixon Eisenhower -Philadelphia Bulletin -Press pool -Washington Star -White House social events -Cabinet -Timing -Helen Thomas -Press room -Washington Star -Ziegler Second term reorganization -Julie Nixon Eisenhower -Job duties -Thomas Kissinger’s press relations -James B. (“Scotty”) Reston -Vietnam negotiations -Denial of conversation -Telephone -John F. Osborne -Nicholas P. Thimmesch -Executive -Kissinger’s sensitivity -Kissinger’s conversation with Ehrlichman -The President’s conversation with Kissinger -Enemies -Respect -Kissinger’s sensitivity -Foreign policy -The President’s trips to the People’s Republic of China [PRC] -

An Analysis of the Prince Edward County, Virginia, Free School Association Lisa A

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 8-1993 Open the doors : an analysis of the Prince Edward County, Virginia, Free School Association Lisa A. Hohl Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Recommended Citation Hohl, Lisa A., "Open the doors : an analysis of the Prince Edward County, Virginia, Free School Association" (1993). Master's Theses. Paper 577. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Open the Doors: An Analysis of the Prince Edward County, Virginia, Free School Association by Lisa A. Hohl Thesis for Master's Degree I University of Richmond I 1993 f' ,\ Thesis director Dr. R. Barry Westin j1ii l When the Supreme Court ordered integration of public l' l : schools in 1954 following Brown vs. Board of Education, ' Virginia responded with a policy of "massive resistance." Public schools were closed in Prince Edward County between 1959 and 1964. This thesis examines the school closings themselves, but concentrates primarily on the creation, implementation, and effect of the Prince Edward County Free School Association, a privately funded school system that operated during the 1963-1964 school year. Initiated by the Kennedy Administration as a one-year, emergency program, the Free Schools were designed to reestablish formal education for the county's black children. This thesis relied primarily upon the uncataloged Free School papers, personal interviews and documents from the John F. -

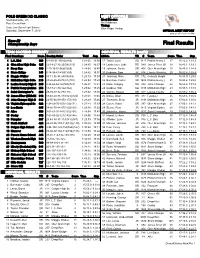

Final Results

POLE GREEN XC CLASSIC MEET OFFICIALS Mechanicsville, VA Meet Director: Pole Green Park Neil Mathews Timing: Host: Lee Davis High School Blue Ridge Timing Saturday, September 7, 2019 OFFICIAL MEET REPORT printed: 9/7/2019 2:19 PM Race #2 Championship Boys Final Results TEAM SCORING SUMMARY INDIVIDUAL RESULTS (cont'd) Final Standings Score Scoring Order Total Avg. Athlete YR # Team Score Time Gap 1 L.C. Bird 108 6-8-30-31-33(82)(166) 1:24:06 16:50 17 Taylor, Luke SO 1417 Patrick Henry ( 17 16:42.2 1:18.2 2 Glen Allen High Scho 125 12-19-27-32-35(59)(115) 1:24:45 16:57 18 Lamberson, Luke SR 589 James River (M 18 16:43.1 1:19.1 3 Deep Run 139 2-13-16-52-56(63)(65) 1:24:04 16:49 19 Johnson, Devin SR 408 Glen Allen High 19 16:48.9 1:24.9 4 Stone Bridge 141 5-14-38-41-43(57)(85) 1:24:42 16:57 20 Rodman, Sam JR 814 Liberty (Bealeto 20 16:52.4 1:28.4 5 Maggie Walker 169 10-11-36-44-68(74)(89) 1:25:13 17:03 21 Jennings, Nate SR 172 Colonial Height - 16:53.0 1:29.0 6 Midlothian High Scho 216 23-26-45-49-73(81)(101) 1:26:53 17:23 22 Burcham, Carter SR 1404 Patrick Henry ( 21 16:53.6 1:29.6 7 Louisa County High S 230 4-24-62-64-76(108)(127) 1:26:41 17:21 23 Dalla, Gregory SR 702 John Champe 22 16:55.4 1:31.4 8 Patrick Henry (Ashlan 254 15-17-21-79-122(162) 1:27:02 17:25 24 Gardner, Will SO 1185 Midlothian High 23 16:55.5 1:31.5 9 Saint Christopher`s 264 29-39-47-72-77(149) 1:27:52 17:35 25 Varney, Bowen SR 917 Louisa County 24 16:59.2 1:35.2 10 James River (Midlothi 316 18-40-58-86-114(123)(124) 1:28:41 17:45 26 Bolles, Brian SR 317 Fauquier 25 16:59.6