Untold Terror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

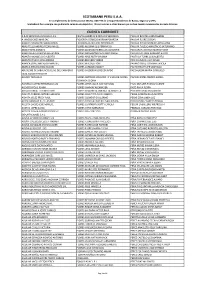

Scotiabank Peru S.A.A. Cuenta Corriente

SCOTIABANK PERU S.A.A. En cumplimiento de la Resolucion SBS No. 0657-99 de la Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y AFPs, Scotiabank Peru cumple con publicar la relación de depósitos, títulos valores u otros bienes que no han tenido movimientos durante 10 años: CUENTA CORRIENTE A & M SERVICIOS AVICOLAS S.R.L. FIESTAS HUERTAS BINDAURA VERONICA PAUCAR BENITES HERMOGENES A. INVERSIONES MAR SAC FIGUEROA CORNEJO NORMA POMPEYA PAUCAR FLORES EDGAR ABAD CUNYARACHE MARIA DORIS FIGUEROA RUBIO JOSE HONORATO PAUCAR PIO DE MENESES ROSALVINA ABAD TELLO ANDRES PEDRO ANGEL FLORES ALEGRIA LUIS FERNANDO PAUCAR TOLEDO ANASTACIO SATURNINO ABAD TROYA DONATO FLORES AMANQUI SERBILLAN AUGUSTIN PAUCARCHUCO RIOS MARGOT JENY ABAD VILLALTA KARINA ALEJANDRA FLORES ANGELDONIS SEGUNDO DANIEL PAULINI ESTRADA ARNALDO ALICIO ABANTO MONGE LUIS ALBERTO FLORES ARCE RUTH VIRGINIA PAUTA LA TORRE LUIS ALBERTO ABANTO PINEDO JOSE ANDRES FLORES BENDEZU YMBER PAXI CALISAYA JULIO CESAR ABARCA LOPEZ ANGELICA MARIBEL FLORES BENDEZU YONI PAYANO ORTIZ GIOVANA TARCILA ABARCA MEDINA EXALTACION FLORES CAHUANA NANCY PAZ RIVERA FELIPE SANTIAGO ABUSLEME DE SABA JACQUELINE DEL CARMEN O FLORES CALDERON JOSE EDUARDO PAZ SALAZAR MARIA CONSUELO SABA DAGACH RICARDO ACENJO TAPIA ELIO FLORES CENTENO EDUARDO O VILCA DE FLORES PAZ SIFUENTES FREDDY ASRAEL DOMINGA GLORIA ACEVEDO CORTEZ FERNANDO LUIS FLORES CHAFLOQUE JOSE ANTONIO PAZO NUNURA RAMOS VICENTE ACEVEDO POLO JUANA FLORES CHAMAY ALEXANDER PAZO PAIVA FLORA ACHAHUI INCATTITO MELCHOR FLORES CHAMBILLA ENRIQUETA GRACIELA PECEROS LOVATON MARCOS ACHATA PAREDES ARTURO GERMAN FLORES CHUCTAYA ALICIA REBECA PECHE DAMIAN JESUS MARTIN ACHATA VELEZ FREDY RAUL FLORES CLEMENT GUILLERMO PECHE ZEÑA LINDA LUZ ACOSHUANCA PEREZ LEANDRO FLORES CONCHA LIVIO BUENAVENTURA PECHO PUÑEZ SANTOS TOMAS ACOSTA CHOZO JOSE MANUEL FLORES CONTRERAS KATTY CAROLA PECORI CABALLERO WILFREDO A ACOSTA LOPEZ ALICIA FLORES CORO ELIBRANDO PEDRAZA CARAZAS TRINIDAD ACOSTA Y DAZA IMPORTACIONES Y FLORES CRUZ ORESTES PEDRAZA CAYCAY JULIO EXPORTACIONES S.A.C. -

N° N° De Dni Apellidos Y Nombres Región De Estudio Ies Sede Carrera Puntaje Final Condición 15356 72694168 Qqueccaño Garay

RESULTADOS DEL CONCURSO DE BECA PERMANENCIA DE ESTUDIOS NACIONAL - CONVOCATORIA 2020 ANEXO N° 02: RELACIÓN DE POSTULANTES NO SELECCIONADOS N° DE REGIÓN DE PUNTAJE N° APELLIDOS Y NOMBRES IES SEDE CARRERA CONDICIÓN DNI ESTUDIO FINAL UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL SAN ANTONIO ABAD DEL 15356 72694168 QQUECCAÑO GARAY, MILAGROS CUSCO SEDE CUSCO CONTABILIDAD 10 NO SELECCIONADO CUSCO UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL SAN ANTONIO ABAD DEL 15357 70454437 QQUECCAÑO HUAMAN, ROSSEL LUCIO CUSCO SEDE CUSCO FISICA 35 NO SELECCIONADO CUSCO UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL SAN ANTONIO ABAD DEL 15358 71091312 QQUECCAÑO QUISPE, ELODIA CUSCO SEDE SAN JERONIMO AGRONOMIA 35 NO SELECCIONADO CUSCO UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AMAZONICA DE MADRE DE EDUCACION: ESPECIALIDAD 15359 44722582 QQUEHUARUCHO CONDORI, LIZBETH MADRE DE DIOS SEDE TAMBOPATA 40 NO SELECCIONADO DIOS PRIMARIA E INFORMATICA UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL SAN ANTONIO ABAD DEL 15360 72215966 QQUELLCCA CARRASCO, DANNY JAYO CUSCO SEDE CUSCO INGENIERIA DE MINAS 30 NO SELECCIONADO CUSCO UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL SAN ANTONIO ABAD DEL 15361 74140891 QQUELLHUA SARCCA, MARITZA CUSCO SEDE YANAOCA EDUCACION INICIAL 40 NO SELECCIONADO CUSCO UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL SAN ANTONIO ABAD DEL 15362 74562202 QQUENAYA APAZA, GABY IVON CUSCO SEDE CUSCO CONTABILIDAD 30 NO SELECCIONADO CUSCO 15363 71558510 QQUENTA MEZA, ROSA INES PUNO UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO SEDE PUNO EDUCACION INICIAL 25 NO SELECCIONADO UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AMAZONICA DE MADRE DE INGENIERIA FORESTAL Y MEDIO 15364 72727352 QQUESO JANCCO, DEISY FLOR MADRE DE DIOS SEDE TAMBOPATA 45 NO SELECCIONADO DIOS AMBIENTE -

El Verdadero Poder De Los Alcaldes

El verdadero poder * Texto elaborado por la redacción de Quehacer con el apoyo del historiador Eduardo Toche y del sociólogo Mario Zolezzi. Fotos: Manuel Méndez 10 de los alcaldes* 11 PODER Y SOCIEDAD n el Perú existe la idea de que las alcaldías representan un escalón Enecesario para llegar a cargos más importantes, como la Presi- dencia de la República. Sin embargo, la historia refuta esta visión ya que, con la excepción de Guillermo Billinghurst, ningún otro alcalde ha llegado a ser presidente. El político del pan grande, sin duda populista, fue derrocado por el mariscal Óscar R. Benavides. Lima siempre ha sido una ciudad conservadora, tanto en sus cos- tumbres como en sus opciones políticas. Durante el gobierno revolucio- nario de Juan Velasco Alvarado, de tinte reformista, la designación “a dedo” de los alcaldes tuvo un perfil más bien empresarial, desvinculado políticamente de las organizaciones populares. Y eso que al gobierno militar le faltaba a gritos contacto con el mundo popular. SINAMOS, una creación estrictamente política del velasquismo, habría podido de lo más bien proponer alcaldes con llegada al universo barrial. Desde su fundación española, Lima ha tenido más de trescientos alcaldes, muchos de ellos nombrados por el gobierno central. El pri- mero fue Nicolás de Ribera, el Viejo, en 1535, y desde esa fecha hasta 1839 se sucedieron más de 170 gestiones municipales. La Constitución de 1839 no consideró la instancia municipal. Recién en 1857 renace la Municipalidad de Lima y fue gobernada por un solo alcalde. El último en tentar el sillón presidencial fue Luis Castañeda Lossio y su participación en la campaña del año 2011 fue bastante pobre, demostrando que una cosa es con guitarra y otra con cajón. -

476 the AMERICAN ALPINE JOURNAL Glaciers That Our Access Was Finally Made Through the Mountain Rampart

476 THE AMERICAN ALPINE JOURNAL glaciers that our access was finally made through the mountain rampart. One group operated there and climbed some of the high-grade towers by stylish and demanding routes, while the other group climbed from a hid- den loch, ringed by attractive peaks, north of the valley and intermingled with the mountains visited by the 1971 St. Andrews expedition (A.A.J., 1972. 18: 1, p. 156). At the halfway stage we regrouped for new objec- tives in the side valleys close to Base Camp, while for the final efforts we placed another party by canoe amongst the most easterly of the smooth and sheer pinnacles of the “Land of the Towers,” while another canoe party voyaged east to climb on the islands of Pamiagdluk and Quvernit. Weather conditions were excellent throughout the summer: most climbs were done on windless and sunny days and bivouacs were seldom contem- plated by the parties abseiling down in the night gloom. Two mountains may illustrate the nature of the routes: Angiartarfik (1845 meters or 6053 feet; Grade III), a complex massive peak above Base Camp, was ascended by front-pointing in crampons up 2300 feet of frozen high-angled snow and then descended on the same slope in soft thawing slush: this, the easiest route on the peak, became impracticable by mid-July when the snow melted off to expose a crevassed slope of green ice; Twin Pillars of Pamiagdluk (1373 meters or 4505 feet; Grade V), a welded pair of abrupt pinnacles comprising the highest peak on this island, was climbed in a three-day sortie by traversing on to its steep slabby east wall and following a thin 300-metre line to the summit crest. -

Análisis De Actitudes De Universitarios Sobre Líderes Políticos, Instituciones, Autoridades, Valores, El Perú Y Personajes Históricos

Revista de Investigación en Psicología ISSN L: 1560 - 909X Vol. 22 - N.º 1 - 2019, pp. 3 - 28 Facultad de Psicología UNMSM DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rinvp.v22i1.16578 Análisis de actitudes de universitarios sobre líderes políticos, instituciones, autoridades, valores, el Perú y personajes históricos Analysis of university attitudes about political leaders, institutions, authorities, values, Peru and historical characters Víctor Montero López 1 Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Recibido: 30 – 04 – 19 Aceptado: 10 – 07 – 19 Resumen A través de una encuesta aplicada a jóvenes de una Universidad Nacional, ellos asociaron diversas palabras para detectar sus actitudes sobre líderes políticos, instituciones, medios de comunicación, autoridades, valores, el Perú y personajes históricos. Priman las valoraciones negativas sobre cada uno de ellos, salvo pocas excepciones. En general, las respuestas per- miten detectar que sus actitudes relacionan las problemáticas a una crisis de partidos políti- cos, de líderes políticos, de gobierno y de régimen político. Los personajes más asociados a la lucha contra la corrupción son más valorados. Se detectaron también cuáles son los peruanos más admirados en la historia y en la actualidad, indicando aspectos positivos y negativos del Perú y los valores diversos de los peruanos. Palabras clave: Líderes políticos; instituciones; valores; psicohistoria; percepciones. Abstract Through a survey applied to young people from a national university, they associated dif- ferent words to detect their attitudes about political leaders, institutions, media, authorities, values, Peru and historical figures, negative valuations prevail over each of them , with few exceptions. In general, the answers allow us to detect that their attitudes relate the problems to a crisis of political parties, political leaders, government and political regime. -

Los Desafíos Del Policymaking En El Perú: Actores, Instituciones Y Reglas De Juego Eduardo Morón Y Cynthia Sanborn

Documento de Trabajo 77 Eduardo Morón y Cynthia Sanborn LOS DESAFÍOS DEL POLICYMAKING EN EL PERÚ: ACTORES, INSTITUCIONES Y REGLAS DE JUEGO Los desafíos del policymaking en el Perú: actores, instituciones y reglas de juego © Universidad del Pacífico Centro de Investigación Avenida Salaverry 2020 Lima 11, Perú Los desafíos del policymaking en el Perú: actores, instituciones y reglas de juego Eduardo Morón y Cynthia Sanborn 1a. edición: febrero 2007 Diseño: Ícono Comunicadores I.S.B.N.: 978-9972-57-108-4 Hecho el depósito legal en la Biblioteca Nacional del Perú: 2007-01039 BUP-CENDI Morón Pastor, Eduardo Los desafíos del policymaking en el Perú: actores, instituciones y reglas de juego / Eduardo Morón y Cynthia Sanborn. -- Lima : Centro de Investigación de la Universidad del Pacífico, 2007. -- (Documento de Trabajo ; 77). /ELABORACIÓN DE POLÍTICAS/POLÍTICA ECONÓMICA/ESTABILIZACIÓN ECONÓMICA/ INSTITUCIONES POLÍTICAS/ESTADO/PARTIDOS POLÍTICOS/ PERÚ/ 35(85) (CDU) Miembro de la Asociación Peruana de Editoriales Universitarias y de Escuelas Superiores (Apesu) y miembro de la Asociación de Editoriales Universitarias de América Latina y el Caribe (Eulac). El Centro de Investigación de la Universidad del Pacífico no se solidariza necesariamente con el contenido de los trabajos que publica. Prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de este documento por cualquier medio sin permiso de la Universidad del Pacífico. Derechos reservados conforme a Ley. 4 Eduardo Morón y Cynthia Sanborn Índice Introducción .................................................................................................... -

Diseño De Programa En Gestión Turística Para Los Pobladores Del Área Natural Protegida Nor Yauyos Cochas, Para Generar Una Adecuada Cultura De Recepción Al Turista

FACULTAD DE HUMANIDADES Arte y Diseño Empresarial DISEÑO DE PROGRAMA EN GESTIÓN TURÍSTICA PARA LOS POBLADORES DEL ÁREA NATURAL PROTEGIDA NOR YAUYOS COCHAS, PARA GENERAR UNA ADECUADA CULTURA DE RECEPCIÓN AL TURISTA Tesis para optar el Título Profesional de Licenciado en Arte y Diseño Empresarial ANTONELLA MAGAGNA LAZARTE Asesor(es): Mtro. Rafael Ernesto Vivanco Álvarez Lima – Perú 2018 ÍNDICE 1. Resumen (Abstract)……………………………………………………………1 2. Introducción……………………………………………………………………..3 3. CAPÍTULO I………………………………………………………………………4 1.1 Descripción del problema encontrado…………………………………...4 1.2 Problema principal…………………………………………………………5 1.3 Problemas secundarios…………………………………………………...6 4. CAPÍTULO II…………………………………………………………….………..6 2.1 Justificación de la investigación...........................................................6 2.2 Objetivo principal…………………………………………………………..7 2.3 Objetivos secundarios………………………………………………….….7 5. CAPÍTULO III…………………………………………………………..…………8 a. Marco teórico……………………………………………………..…………..8 3.1 Áreas Naturales Protegidas………………………………………..…………8 3.1.1 Clasificación en el Perú…………………………………..…………..10 Desarrollo sostenido de la comunidad………………………………..……….12 3.2 Reserva paisajística (RP)…………………………………………..………..12 3.3 Reserva Paisajística de Nor Yauyos Cochas (RPNYC)………………..…13 3.4 Huancaya……………………………………………………………………....14 3.4.1 Población y demografía……………………………………………....14 a) Indicadores culturales de la comunidad……………………..…..16 b) Actividades económicas de las comunidades locales………....18 3.4.2 Antecedentes e historia……………………………………………....19 -

Siguiendo La Coyuntura 1990-1992: “Y La Violencia Y El Desorden Crearon a Fujimori…”

Discursos Del Sur / ISSN: 2617-2283 | 117 Siguiendo la coyuntura 1990-1992: “y la violencia y el desorden crearon a Fujimori…” Recibido: 06/09/2018 SANTIAGO PEDRAGLIO1 Aprobado: 02/11/2018 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú [email protected] RESUMEN Este artículo se centra en las elecciones de 1990, en el contexto de una aguda crisis económica y política que permitió la victoria, sobre Mario Vargas Llosa, de un desconocido: Alberto Fujimori. Finalizado el periodo electoral, la situación de excepción —configurada gradualmente durante la década de 1980 por el accionar de Sendero Luminoso, la constitución de comandos político-militares y la gran crisis política y económica— ingresó en una nueva coyuntura. Fujimori cambió su discurso político e inició la organización de una amplia coalición conservadora en torno a un proyecto neoliberal Palabras clave: Perú, Alberto Fujimori, Sendero Luminoso, situación de excepción, coyuntura. Following the moment 1990-1992: “and violence and disorder created Fujimori...” ABSTRACT This article focuses on the 1990 elections, in the context of an acute economical and political crisis that allowed an unknown, Alberto Fujimori, the victory over Mario Vargas Llosa. After this electoral period, the state of exception —configured gradually during the decade of 1980 by the actions of the Shining Path, the constitution of paramilitary commandos and the generalized economic and political crisis— entered into a new context. Fujimori changed his political discourse and initiated the organization of a broad conservative coalition around a neoliberal project. Keywords: Peru, Alberto Fujimori, Shining Path, state of exception. 1 Adaptación de los capítulos I y II de la tesis Cómo se llegó a la dictadura consentida. -

PDF Agrupado

2 En portada V~ernes. 22 de julio~’*’° del 2016 195 anosde La izquierda peruana a lo largo de los procesos electorales presidenciales 0 1928-~ 1930 ,-0 1958 ~O 1963 En octubre es fundado el Siendo Eudocio Gana Manuel Prado Hugo Blanco La izquierda no Partido Socialista Peruano Ravines secretario Ugart~he del impulsa la Federación tuvo participación por Jos¿" Carlos Mari~tegui, general se cambia frente de de Trabajadol~s institucional teniendo como una de sus de nombre al Partido ConoE~rtación Campesinos. cuando Fernando líneas de acción la unión Socialista por Nacicnal. Belaunde llega a obrero-campesina. Partido Comunista En esa alianza se la presidencia en Este partido y el Apra Peruano. indul], entre otros las nuevas fueron prohibidos durante ~UlXtS pollticos, el elecciones. el "Oncenio" de Augusto B. 1936 FartkJo Comunlsla En esta etapa se Legula. Peruano, que había inicia la radical- Luis Antonio Eguiguren recib do la orden ización en el creó el Partido Social inteo~acional de discurso de la Demócrata, concentrarse en la izquierda. e intenta conquistar el lucha contra la Luis de la Puente voto de tendencia amenaza fascista. Uceda conforma el izquierdista Movimiento de (que había sido Izquierda descalificado por el Revolucionaria gobierno). Tras a II Guerra (MIR). El candidato habría Mur~tial, en medio obtenido un alto de una atmósfera respaldo, pero el JNE democrática se anuló las elecciones crea el Frente Hugo Blanco bajo el pretexto de que Demoo’áflco el candidato habla Nadonal (FDN), recibido votos apristas una gran coalición y de izquierda. de la que formaba ~rte el Partido En estas elecciones Com Jnista y per primera vez grupos indepen- participan dientes. -

Diversidad Y Fragmentación De Una Metrópoli Emergente

www.flacsoandes.edu.ec CIUDADES Volumen 3 Pablo Vega Centeno, editor Lima, diversidad y fragmentación de una metrópoli emergente OLACCHI Organización Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Centros Históricos Editor general Fernando Carrión Coordinador editorial Manuel Dammert G. Comité editorial Fernando Carrión Michael Cohén Pedro Pírez Alfredo Rodríguez Manuel Dammert G. Diseño y diagramación Antonio Mena Edición de estilo Andrea Pequeño Impresión Crearimagen ISBN: 978-9978-370-06-3 © OLACCHI El Quinde N45-72 yDe Las Golondrinas Tel.: (593-2) 2462 739 [email protected] www.olacchi.org Quito, Ecuador Primera edición: noviembre de 2009 Contenido Presentación................................................................................ 7 Introducción............................................................. 9 Pablo Vega Centeno I. Geografía urbana y globalización La ciudad latinoamericana: la construcción de un modelo. Vigencia y perspectivas ............ ............................. 27 Jürgen Bdhr y Axel Borsdorf Lima de los noventas: neoliberalismo, arquitectura y urbanismo.................................. 47 Wiley Ludeña Dimensión metropolitana de la globalización: lima a fines del siglo X X ............................................................ 71 Miriam Chion La formación de enclaves residenciales en Lima en el contexto de la inseguridad ........................... 97 Jorg Plóger II. Cultura urbana Urbanización temprana en Lima, 1535-1900 ........................... 143 Aldo Panfichi Los rostros cambiantes de la ciudad: cultura -

Apogeo Y Crisis De La Izquierda Peruana

APOGEO Y CRISIS DE LA IZQUIERDA PERUANA HABLAN SUS PROTAGONISTAS Alberto Adrianzén (Editor) Apogeo y crisis de la izquierda peruana. Hablan sus protagonistas. © Instituto para la Democracia y la Asistencia Electoral (IDEA Internacional) © Universidad Antonio Ruiz de Montoya (UARM) IDEA Internacional IDEA Internacional Universidad Antonio Ruiz de Montoya Strömsborg Oficina Región Andina Av. Paso de los Andes 970 – Pueblo Libre SE-103 34 Estocolmo Av. San Borja Norte 1123 Lima 21 / Perú Suecia San Borja, Lima 41-Perú Teléfono: (51 1) 719-5990 Tel.: +46 8 698 37 00 Tel.: +51 1 203 7960 www.uarm.edu.pe Fax: +46 8 20 24 22 Fax: +51 1 437 7227 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] librosuarm.blogspot.com www.idea.int Las opiniones expresadas en esta publicación no representan necesariamente los puntos de vista de IDEA Internacional ni de la Universidad Antonio Ruiz de Montoya, de sus juntas directivas ni de los miembros de sus consejos y/o Estados miembros. Esta publicación es independiente de ningún interés específico nacional o político. Toda solicitud de permisos para usar o traducir todo o alguna parte de esta publicación debe hacerse a: IDEA Internacional Universidad Antonio Ruiz de Montoya Strömsborg Av. Paso de los Andes 970 – Pueblo Libre SE-103 34 Estocolmo Lima 21 Perú Suecia Primera edición: diciembre de 2011 Tiraje: 1,000 ejemplares ISBN: 978-91-86565-47-3 Hecho el Depósito Legal en la Biblioteca Nacional del Perú Nº: 2011-16120 Foto de carátula: cortesía revista Caretas Impreso en el Perú por: MAD CORP. SAC Jr. -

REPUBLIC of PERU BIDDING TERMS Special

REPUBLIC OF PERU PRIVATE INVESTMENT PROMOTION AGENCY BIDDING TERMS Special Public Bidding for the execution of the process: Single Concession for the provision of Public Telecommunication Services and Assignment at the national level of the frequency range 1,750 - 1,780 MHz and 2,150 - 2,180 MHz and 2,300 - 2,330 MHz PROJECT PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT May 2021 Important: This is an unofficial translation. In the case of divergence between the English and Spanish text, the version in Spanish shall prevail. Special Public Bidding for the execution of the process: Single Concession for the provision of Public Telecommunication Services and Assignment at the national level of the frequency range 1,750 - 1,780 MHz and 2,150 - 2,180 MHz and 2,300 - 2,330 MHz 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Background ........................................................................................................................................ 6 2. Purpose and Characteristics of the Bidding .................................................................................... 7 2.1. Call ............................................................................................................................................ 7 2.2. Characteristics of the Bidding ................................................................................................... 8 2.2.1. Modality of the Special Public Bidding .............................................................................. 8 2.2.2. Modality of Projects in Assets ..........................................................................................