Uncovering the Source of Alchemy's Association With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alchemical Culture and Poetry in Early Modern England

Alchemical culture and poetry in early modern England PHILIP BALL Nature, 4–6 Crinan Street, London N1 9XW, UK There is a longstanding tradition of using alchemical imagery in poetry. It first flourished at the end of the sixteenth century, when the status of alchemy itself was revitalised in European society. Here I explain the reasons for this resurgence of the Hermetic arts, and explore how it was manifested in English culture and in particular in the literary and poetic works of the time. In 1652 the English scholar Elias Ashmole published a collection of alchemical texts called Theatrum Chymicum Britannicum, comprising ‘Several Poeticall Pieces of Our Most Famous English Philosophers’. Among the ‘chemical philosophers’ represented in the volume were the fifteenth-century alchemists Sir George Ripley and Thomas Norton – savants who, Ashmole complained, were renowned on the European continent but unduly neglected in their native country. Ashmole trained in law, but through his (second) marriage to a rich widow twenty years his senior he acquired the private means to indulge at his leisure a scholarly passion for alchemy and astrology. A Royalist by inclination, he had been forced to leave his London home during the English Civil War and had taken refuge in Oxford, the stronghold of Charles I’s forces. In 1677 he donated his impressive collection of antiquities to the University of Oxford, and the building constructed to house them became the Ashmolean, the first public museum in England. Ashmole returned to London after the civil war and began to compile the Theatrum, which was intended initially as a two-volume work. -

Book Reviews

Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 35, Number 2 (2010) 125 BOOK REVIEWS Rediscovery of the Elements. James I. and Virginia Here you can find mini-biographies of scientists, R. Marshall. JMC Services, Denton TX. DVD, Web detailed geographic routes to each of the element discov- Page Format, accessible by web browsers and current ery sites, cities connected to discoveries, maps (354 of programs on PC and Macintosh, 2010, ISBN 978-0- them) and photos (6,500 from a base of 25,000), a time 615-30793-0. [email protected] $60.00 line of discoveries, 33 background articles published by ($50.00 for nonprofit organizations {schools}, $40.00 the authors in The Hexagon, and finally a link to “Tables at workshops.) and Text Files,” a compilation probably containing more information than all the rest of the DVD. I will discuss this later, except for one file in it: “Background Before the launching of this review it needs to be and Scope.” Here the authors point out that the whole stated that DVDs are not viewable unless your computer project of visiting the sources, mines, quarries, museums, is equipped with a DVD reader. I own a 2002 Microsoft laboratories connected with each element, only became Word XP computer, but it failed. I learned that I needed possible very recently. Four recent developments opened a piece of hardware, a DVD reader. It can be installed the door: first, the fall of the Iron Curtain allowing easy inside the computer or attached externally. The former is access to Eastern Europe including Russia; second, the cheaper, in fact quite inexpensive, unless you have to pay universality of email and internet communication; third, for the installation. -

Newton's Dark Secrets

Original broadcast: November 15, 2005 BEFORE WATCHING Newton’s Dark Secrets 1 Ask students what they know about Sir Isaac Newton. List student answers on the board. Where and when did he live? What did he do? PROGRAM CONTENTS What is he most known for? NOVA presents the life and science of 2 Organize students into three Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1727), one of groups. As they watch, have each the greatest scientists who ever lived. group take notes on one of the following topics: Newton’s key scientific and mathematical discov- The program: eries, his religious journey, and his • chronicles Newton’s upbringing in the early part of the work in alchemy. Scientific Revolution. • recounts Newton’s attendance at Trinity College at Cambridge University in England, where he studied the latest scientific ideas, AFTER WATCHING and his return to his hometown of Woolsthorpe four years later when the plague struck Cambridge. 1 Have students who took notes on • reviews the advances Newton made in gravity, calculus, and the the same topic meet and present their notes. Ask the following composition of light while he was at Woolsthorpe. questions as different teams • relates Newton’s return to Cambridge, where he was appointed the share their notes: What were some Lucasian Professor of Mathematics, a chair currently held by physicist of Newton’s mathematical and Stephen Hawking. scientific contributions? Which are • reports how Newton solved the problem of chromatic aberration in important in the world today? What role did religion play in his life? refracting telescopes by designing and building a reflecting telescope Why was he interested in alchemy? based on mirrors rather than lenses. -

Tensions Between Scientia and Ars in Medieval Natural Philosophy and Magic Isabelle Draelants

The notion of ‘Properties’ : Tensions between Scientia and Ars in medieval natural philosophy and magic Isabelle Draelants To cite this version: Isabelle Draelants. The notion of ‘Properties’ : Tensions between Scientia and Ars in medieval natural philosophy and magic. Sophie PAGE – Catherine RIDER, eds., The Routledge History of Medieval Magic, p. 169-186, 2019. halshs-03092184 HAL Id: halshs-03092184 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03092184 Submitted on 16 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. This article was downloaded by: University College London On: 27 Nov 2019 Access details: subscription number 11237 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Routledge History of Medieval Magic Sophie Page, Catherine Rider The notion of properties Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613192-14 Isabelle Draelants Published online on: 20 Feb 2019 How to cite :- Isabelle Draelants. 20 Feb 2019, The notion of properties from: The Routledge History of Medieval Magic Routledge Accessed on: 27 Nov 2019 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613192-14 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. -

A Lexicon of Alchemy

A Lexicon of Alchemy by Martin Rulandus the Elder Translated by Arthur E. Waite John M. Watkins London 1893 / 1964 (250 Copies) A Lexicon of Alchemy or Alchemical Dictionary Containing a full and plain explanation of all obscure words, Hermetic subjects, and arcane phrases of Paracelsus. by Martin Rulandus Philosopher, Doctor, and Private Physician to the August Person of the Emperor. [With the Privilege of His majesty the Emperor for the space of ten years] By the care and expense of Zachariah Palthenus, Bookseller, in the Free Republic of Frankfurt. 1612 PREFACE To the Most Reverend and Most Serene Prince and Lord, The Lord Henry JULIUS, Bishop of Halberstadt, Duke of Brunswick, and Burgrave of Luna; His Lordship’s mos devout and humble servant wishes Health and Peace. In the deep considerations of the Hermetic and Paracelsian writings, that has well-nigh come to pass which of old overtook the Sons of Shem at the building of the Tower of Babel. For these, carried away by vainglory, with audacious foolhardiness to rear up a vast pile into heaven, so to secure unto themselves an immortal name, but, disordered by a confusion and multiplicity of barbarous tongues, were ingloriously forced. In like manner, the searchers of Hermetic works, deterred by the obscurity of the terms which are met with in so many places, and by the difficulty of interpreting the hieroglyphs, hold the most noble art in contempt; while others, desiring to penetrate by main force into the mysteries of the terms and subjects, endeavour to tear away the concealed truth from the folds of its coverings, but bestow all their trouble in vain, and have only the reward of the children of Shem for their incredible pain and labour. -

Alchemy Rediscovered and Restored

ALCHEMY REDISCOVERED AND RESTORED BY ARCHIBALD COCKREN WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE EXTRACTION OF THE SEED OF METALS AND THE PREPARATION OF THE MEDICINAL ELIXIR ACCORDING TO THE PRACTICE OF THE HERMETIC ART AND OF THE ALKAHEST OF THE PHILOSOPHER TO MRS. MEYER SASSOON PHILADELPHIA, DAVID MCKAY ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN 1941 Alchemy Rediscovered And Restored By Archibald Cockren. This web edition created and published by Global Grey 2013. GLOBAL GREY NOTHING BUT E-BOOKS TABLE OF CONTENTS THE SMARAGDINE TABLES OF HERMES TRISMEGISTUS FOREWORD PART I. HISTORICAL CHAPTER I. BEGINNINGS OF ALCHEMY CHAPTER II. EARLY EUROPEAN ALCHEMISTS CHAPTER III. THE STORY OF NICHOLAS FLAMEL CHAPTER IV. BASIL VALENTINE CHAPTER V. PARACELSUS CHAPTER VI. ALCHEMY IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES CHAPTER VII. ENGLISH ALCHEMISTS CHAPTER VIII. THE COMTE DE ST. GERMAIN PART II. THEORETICAL CHAPTER I. THE SEED OF METALS CHAPTER II. THE SPIRIT OF MERCURY CHAPTER III. THE QUINTESSENCE (I) THE QUINTESSENCE. (II) CHAPTER IV. THE QUINTESSENCE IN DAILY LIFE PART III CHAPTER I. THE MEDICINE FROM METALS CHAPTER II. PRACTICAL CONCLUSION 'AUREUS,' OR THE GOLDEN TRACTATE SECTION I SECTION II SECTION III SECTION IV SECTION V SECTION VI SECTION VII THE BOOK OF THE REVELATION OF HERMES 1 Alchemy Rediscovered And Restored By Archibald Cockren THE SMARAGDINE TABLES OF HERMES TRISMEGISTUS said to be found in the Valley of Ebron, after the Flood. 1. I speak not fiction, but what is certain and most true. 2. What is below is like that which is above, and what is above is like that which is below for performing the miracle of one thing. -

The Importance of Translation Mathematics Old Script ABSTRACT

Malaysian Journal of Mathematical Sciences 3(1): 55-66 (2009) The Importance of Translation Mathematics Old Script 1Shahrul Nizam Ishak, 2Noor Hayati Marzuki, 3Jamaludin Md. Ali School of Mathematical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT In this paper, a concise discussion of the text study will be carried out by focusing on the significant of Malay mathematics old script translation. We also discuss the importance of the translation work that need to emphasize. Stages of the translation period based on history knowledge also been highlighted. An example of the translation from Rau ḍat al-Ḥuss āb f ī ‘Ilm al-Ḥis āb that was written by Malay ‘Ulama 1 in 1307H/1893M is also shown here. The book was printed in Egypt and has been used in teaching and learning among the student at the Holy Mosque ( Masjid al- Har ām). Therefore, from this work hope that the introduction of the book presented here is sufficient to stimulate interest in readers and researchers to embark and investigate the beauty and the power of script translation in providing more knowledge especially in the mathematics education area. Keywords: Mathematics Translation, Old Script, Rau ḍat al-Ḥuss āb. INTRODUCTION The amount of translation into Arabic from Greek, Syrian, Persian and Sanskrit was at its peak during the ninth and tenth century. ‘Ulama of Islam, Christianity, Judaism and even Zoroastrianism were employed in the translation and writing new scientific masterpieces. In the course of time the works of Euclid, Ptolemy, Aristotle, Apollonius, Archimedes, Heron, Diophantus and the Hindus were accessible in Arabic. -

Alchemy Archive Reference

Alchemy Archive Reference 080 (MARC-21) 001 856 245 100 264a 264b 264c 337 008 520 561 037/541 500 700 506 506/357 005 082/084 521/526 (RDA) 2.3.2 19.2 2.8.2 2.8.4 2.8.6 3.19.2 6.11 7.10 5.6.1 22.3/5.6.2 4.3 7.3 5.4 5.4 4.5 Ownership and Date of Alternative Target UDC Nr Filename Title Author Place Publisher Date File Lang. Summary of the content Custodial Source Rev. Description Note Contributor Access Notes on Access Entry UDC-IG Audience History 000 SCIENCE AND KNOWLEDGE. ORGANIZATION. INFORMATION. DOCUMENTATION. LIBRARIANSHIP. INSTITUTIONS. PUBLICATIONS 000.000 Prolegomena. Fundamentals of knowledge and culture. Propaedeutics 001.000 Science and knowledge in general. Organization of intellectual work 001.100 Concepts of science Alchemyand knowledge 001.101 Knowledge 001.102 Information 001102000_UniversalDecimalClassification1961 Universal Decimal Classification 1961 pdf en A complete outline of the Universal Decimal Classification 1961, third edition 1 This third edition of the UDC is the last version (as far as I know) that still includes alchemy in Moreh 2018-06-04 R 1961 its index. It is a useful reference documents when it comes to the folder structure of the 001102000_UniversalDecimalClassification2017 Universal Decimal Classification 2017 pdf en The English version of the UDC Online is a complete standard edition of the scheme on the Web http://www.udcc.org 1 ThisArchive. is not an official document but something that was compiled from the UDC online. Moreh 2018-06-04 R 2017 with over 70,000 classes extended with more than 11,000 records of historical UDC data (cancelled numbers). -

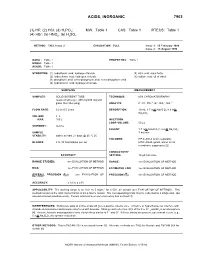

NIOSH Method 7903: Acids, Inorganic

ACIDS, INORGANIC 7903 (1) HF; (2) HCl; (3) H3PO4; MW: Table 1 CAS: Table 1 RTECS: Table 1 (4) HBr; (5) HNO3; (6) H2SO4 METHOD: 7903, Issue 2 EVALUATION: FULL Issue 1: 15 February 1984 Issue 2: 15 August 1994 OSHA : Table 1 PROPERTIES: Table 1 NIOSH: Table 1 ACGIH: Table 1 SYNONYMS: (1) hydrofluoric acid; hydrogen fluoride (5) nitric acid; aqua fortis (2) hydrochloric acid; hydrogen chloride (6) sulfuric acid; oil of vitriol (3) phosphoric acid; ortho-phosphoric acid; meta-phosphoric acid (4) hydrobromic acid; hydrogen bromide SAMPLING MEASUREMENT SAMPLER: SOLID SORBENT TUBE TECHNIQUE: ION CHROMATOGRAPHY (washed silica gel, 400 mg/200 mg with 3 2 glass fiber filter plug) ANALYTE: F , Cl , PO4 , Br , NO3 , SO4 FLOW RATE: 0.2 to 0.5 L/min DESORPTION: 10 mL 1.7 mM NaHCO3/1.8 mM Na2CO3 VOL-MIN: 3 L -MAX: 100 L INJECTION LOOP VOLUME: 50 µL SHIPMENT: routine ELUENT: 1.7 mM NaHCO3/1.8 mM Na2CO3; SAMPLE 3 mL/min STABILITY: stable at least 21 days @ 25 °C [1] COLUMNS: HPIC-AS4A anion separator, BLANKS: 2 to 10 field blanks per set HPIC-AG4A guard, anion micro membrane suppressor [2] CONDUCTIVITY ACCURACY SETTING: 10 µS full scale RANGE STUDIED: see EVALUATION OF METHOD RANGE: see EVALUATION OF METHOD BIAS: see EVALUATION OF METHOD ESTIMATED LOD: see EVALUATION OF METHOD OVERALL PRECISION (S ˆ ): see EVALUATION OF PRECISION (S ): see EVALUATION OF METHOD METHOD rT r ACCURACY: ± 12 to ± 23% APPLICABILITY: The working range is ca. 0.01 to 5 mg/m 3 for a 50-L air sample (see EVALUATION OF METHOD). -

Manly Palmer Hall Collection of Alchemical Manuscripts, 1500-1825

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf838nb2kp Online items available Finding aid for the Manly Palmer Hall collection of alchemical manuscripts, 1500-1825 Finding aid prepared by Trevor Bond. Finding aid for the Manly Palmer 950053 1 Hall collection of alchemical manuscripts, 1500-1825 ... Descriptive Summary Title: Manly Palmer Hall collection of alchemical manuscripts Date (inclusive): 1500-1825 Number: 950053 Creator/Collector: Hall, Manly P. (Manly Palmer), 1901-1990 Physical Description: 7.5 linear feet(243 vols.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California, 90049-1688 (310) 440-7390 Abstract: A collection of 243 manuscripts detailing the arts of Alchemy, Hermeticism, Rosicrucianism, and Masonry, gathered by Manly Palmer Hall, author and researcher in the realms of mysticism and the occult. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy. Language: Collection material is in Latin Biographical/Historical Note Manley Hall was born in 1901,in Peterborough, Canada, to William S. and Louise Palmer Hall. The Hall family moved to the United States in 1904 and lived for a time in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Manly Hall settled in Los Angeles in 1919. As a young man he became interested in occult matters. He subsequently joined a number of societies, among them the Theosophical Society, the Freemasons, the Societas Rosecruciana in Civitatibus Foederatis, and the American Federation of Astrologers. In 1922 Manly Hall wrote his first book on philosophy/religion, Initiates of the Flame. According to Hall, he began collecting works on mysticism and the esoteric sciences: "late in the fall of 1922, the plan for a comprehensive work on the symbolism of western mystical societies began to take shape in my mind. -

Académie Des Sciences Et Belles Lettres (Nancy) 83 Académie

INDEX Académie des Sciences et Belles Lettres atomism 180 (Nancy) 83 Austin, William 169 Académie Royale des Sciences 7–13, 77, 84, 93, 125, 126, 129, 178, 181–82, 183 Bacon, Francis 68 academies, scientific 82, 189 Baconianism 91, 149 Achard, Franz Carl 126 Baglivi, Giorgio 67–68 acid-alkali theory 5, 49, 50, 57, 71 Baldinger, E. G. 102 active principles 7, 69 Banks, Joseph 159, 160 aerial niter 55 Baumé, Antoine 23, 78, 84, 86, 87, 91 affinity 16, 45, 92, 93, 142, 117, 157, 180 Becher, Johann Joachim 8, 9, 23, 28–30, Agricola, Georg 140 35–36, 90 agriculture 145–47 Becoeur, Jean Baptiste (fils) 79 Agrippa von Nettesheim, Cornelius 189 Beddoes, Thomas 157–76, 187 air 57–58 Beguin, Jean 101 fixed 58, 139, 142, 144, 161 Bensaude-Vincent, Bernadette 14, 188 Albertus Magnus 35 Bergman, Torbern 20n20, 161 alchemy 3, 23–43, 101, 102, 106, 115, 180, Berlin Society of Sciences/Academy of 183, 185, 189 (see also transmutation Sciences 100, 116, 124, 125, 126, 128 and chrysopoeia) Bernoulli, Johann 6 alcohol 51–52 Bindheim, Johann Jacob 110, 133 alkahest 9, 11, 12 Black, Joseph 23, 139, 141–45, 161, 165, 187 Alpers, Svetlana 66 Bloch, Marcus Elieser 125 Alston, Charles 142 Boas Hall, Marie 4 analysis 15, 52, 54, 91, 142, 181 Boecler, Johann 80 by fire 47 Boerhaave, Herman 13–14, 45–61, 63–76, Anderson, James 139–56, 187 85, 90, 117, 157, 183, 184 anesthesia 170 Bohn, Johannes 54–55 antimony 16 Bollmann, Viktor Friedrich 106 apothecaries 81–90, 97–130, 188–89 book market 24–43, 102, 117 Apothecary’s Hall (London) 116 Borrichius, Olaus 35 apparatus 107, 164–65 botanical gardens 82 apprenticeship 99–114 Böttger, Johann Friedrich 29–30, 38 Apreece, Jane 171 Boulduc, Simon 117 Arnald of Villanova 35 Boulton, Matthew 116 assaying 97, 116, 124, 145–46 Boulton, Matthew Robinson 103, 159, 167 195 196 INDEX Bourdelin, Hilaire-Marin 88 Cullen, William 139, 141–43, 187 Boyle, Robert 13, 46–48, 50–51, 54, 179, 184 Cunningham, Andrew 65 Brande, August Hermann 125 Cyprian, A. -

The Emerald Tablet of Hermes

The Emerald Tablet of Hermes Multiple Translations The Emerald Tablet of Hermes Table of Contents The Emerald Tablet of Hermes.........................................................................................................................1 Multiple Translations...............................................................................................................................1 History of the Tablet................................................................................................................................1 Translations From Jabir ibn Hayyan.......................................................................................................2 Another Arabic Version (from the German of Ruska, translated by 'Anonymous')...............................3 Twelfth Century Latin..............................................................................................................................3 Translation from Aurelium Occultae Philosophorum..Georgio Beato...................................................4 Translation of Issac Newton c. 1680........................................................................................................5 Translation from Kriegsmann (?) alledgedly from the Phoenician........................................................6 From Sigismund Bacstrom (allegedly translated from Chaldean)..........................................................7 From Madame Blavatsky.........................................................................................................................8