Photointerpretation of the Lunar Surface* (With Fold-In Maf) Supplementt)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

88 PAJ 116 Anne Carson Reading Text in STACKS © Michael Hart, 2008

Anne Carson reading text in STACKS © Michael Hart, 2008. Courtesy Jonah Bokaer Choreography. 88 PAJ 116 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/PAJJ_a_00369 by guest on 01 October 2021 Stacks Anne Carson STACK OF THE SEAS OF THE MOON IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER Mare Aliorum Sea of Others Mare Ambulationis Sea of Walking Mare Anguis Snake Sea Mare Australe Sea to the South Mare Crisium Sea of Crises Mare Dormiendi Nuditer Sea of Sleeping Naked Mare Frigoris Sea of Cold Mare Humboldtianum Humboldt’s Sea Mare Humorum Sea of Moistures Mare Imbrium Sea of Rains Mare Lunae Quaestionum Sea of the Problems of the Moon Mare Marginis Border Sea Mare Moscoviense Moscow Sea Mare Nectaris Sea of Nectar Mare Nocte Ambulationis Sea of Walking at Night Mare Nubium Sea of Clouds Mare Orientale Sea to the East Mare Personarum Sea of Masks Mare Phoenici Phoenician Sea Mare Phoenicopterorum Sea of Flamingos Mare Pudoris Sea of Shame Mare Relictum Sea of Detroit Mare Ridens Laughing Sea Mare Smythii Sea of Smyth Mare Spumans Foaming Sea Mare Tempestivitatis Sea of What Frank O’Hara Calls “Cantankerous Filaments of a Larger Faintheartedness Like Loving Summer” Mare Vituperationis Sea of Blaming © 2017 Anne Carson PAJ 116 (2017), pp. 89–108. 89 doi:10.1162/PAJJ _a_00369 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/PAJJ_a_00369 by guest on 01 October 2021 THUNDERSTORM STACK A bird flashed by as if mistaken then it starts. We do not think speed of life. We do not think why hate Jezebel? We think who’s that throwing trees against the house? Jezebel was a Phoenician. -

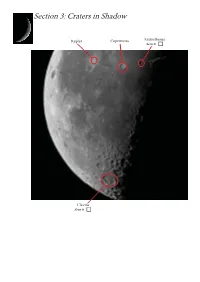

Craters in Shadow

Section 3: Craters in Shadow Kepler Copernicus Eratosthenes Seen it Clavius Seen it Section 3: Craters in Shadow Visibility: A pair of binoculars is the minimum requirement to see these features. When: Look for them when the terminator’s close by, typically a day before last quarter. Not all craters are best seen when the Sun is high in the lunar sky - in fact most aren’t! If craters aren’t par- ticularly bright or dark, they tend to disappear into the background when the Moon’s phase is close to full. These craters are best seen when the ‘terminator’ is nearby, or when the Sun is low in the lunar sky as seen from the crater. This causes oblique lighting to fall on the crater and create exaggerated shadows. Ultimately, this makes the crater look more dramatic and easier to see. We’ll use this effect for the next section on lunar mountains, but before we do, there are a couple of craters that we’d like to bring to your attention. Actually, the Moon is covered with a whole host of wonderful craters that look amazing when the lighting is oblique. During the summer and into the early autumn, it’s the later phases of the Moon are best positioned in the sky - the phases following full Moon. Unfortunately, this means viewing in the early hours but don’t worry as we’ve kept things simple. We just want to give you a taste of what a shadowed crater looks like for this marathon, so the going here is really pretty easy! First, locate the two craters Kepler and Copernicus which were marathon targets pointed out in Section 2. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

Sky and Telescope

SkyandTelescope.com The Lunar 100 By Charles A. Wood Just about every telescope user is familiar with French comet hunter Charles Messier's catalog of fuzzy objects. Messier's 18th-century listing of 109 galaxies, clusters, and nebulae contains some of the largest, brightest, and most visually interesting deep-sky treasures visible from the Northern Hemisphere. Little wonder that observing all the M objects is regarded as a virtual rite of passage for amateur astronomers. But the night sky offers an object that is larger, brighter, and more visually captivating than anything on Messier's list: the Moon. Yet many backyard astronomers never go beyond the astro-tourist stage to acquire the knowledge and understanding necessary to really appreciate what they're looking at, and how magnificent and amazing it truly is. Perhaps this is because after they identify a few of the Moon's most conspicuous features, many amateurs don't know where Many Lunar 100 selections are plainly visible in this image of the full Moon, while others require to look next. a more detailed view, different illumination, or favorable libration. North is up. S&T: Gary The Lunar 100 list is an attempt to provide Moon lovers with Seronik something akin to what deep-sky observers enjoy with the Messier catalog: a selection of telescopic sights to ignite interest and enhance understanding. Presented here is a selection of the Moon's 100 most interesting regions, craters, basins, mountains, rilles, and domes. I challenge observers to find and observe them all and, more important, to consider what each feature tells us about lunar and Earth history. -

Pete Aldridge Well, Good Afternoon, Ladies and Gentlemen, and Welcome to the Fifth and Final Public Hearing of the President’S Commission on Moon, Mars, and Beyond

The President’s Commission on Implementation of United States Space Exploration Policy PUBLIC HEARING Asia Society 725 Park Avenue New York, NY Monday, May 3, and Tuesday, May 4, 2004 Pete Aldridge Well, good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the fifth and final public hearing of the President’s Commission on Moon, Mars, and Beyond. I think I can speak for everyone here when I say that the time period since this Commission was appointed and asked to produce a report has elapsed at the speed of light. At least it seems that way. Since February, we’ve heard testimonies from a broad range of space experts, the Mars rovers have won an expanded audience of space enthusiasts, and a renewed interest in space science has surfaced, calling for a new generation of space educators. In less than a month, we will present our findings to the White House. The Commission is here to explore ways to achieve the President’s vision of going back to the Moon and on to Mars and beyond. We have listened and talked to experts at four previous hearings—in Washington, D.C.; Dayton, Ohio; Atlanta, Georgia; and San Francisco, California—and talked among ourselves and we realize that this vision produces a focus not just for NASA but a focus that can revitalize US space capability and have a significant impact on our nation’s industrial base, and academia, and the quality of life for all Americans. As you can see from our agenda, we’re talking with those experts from many, many disciplines, including those outside the traditional aerospace arena. -

Planetary Science : a Lunar Perspective

APPENDICES APPENDIX I Reference Abbreviations AJS: American Journal of Science Ancient Sun: The Ancient Sun: Fossil Record in the Earth, Moon and Meteorites (Eds. R. 0.Pepin, et al.), Pergamon Press (1980) Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta Suppl. 13 Ap. J.: Astrophysical Journal Apollo 15: The Apollo 1.5 Lunar Samples, Lunar Science Insti- tute, Houston, Texas (1972) Apollo 16 Workshop: Workshop on Apollo 16, LPI Technical Report 81- 01, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston (1981) Basaltic Volcanism: Basaltic Volcanism on the Terrestrial Planets, Per- gamon Press (1981) Bull. GSA: Bulletin of the Geological Society of America EOS: EOS, Transactions of the American Geophysical Union EPSL: Earth and Planetary Science Letters GCA: Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta GRL: Geophysical Research Letters Impact Cratering: Impact and Explosion Cratering (Eds. D. J. Roddy, et al.), 1301 pp., Pergamon Press (1977) JGR: Journal of Geophysical Research LS 111: Lunar Science III (Lunar Science Institute) see extended abstract of Lunar Science Conferences Appendix I1 LS IV: Lunar Science IV (Lunar Science Institute) LS V: Lunar Science V (Lunar Science Institute) LS VI: Lunar Science VI (Lunar Science Institute) LS VII: Lunar Science VII (Lunar Science Institute) LS VIII: Lunar Science VIII (Lunar Science Institute LPS IX: Lunar and Planetary Science IX (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute LPS X: Lunar and Planetary Science X (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute) LPS XI: Lunar and Planetary Science XI (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute) LPS XII: Lunar and Planetary Science XII (Lunar and Planetary Institute) 444 Appendix I Lunar Highlands Crust: Proceedings of the Conference in the Lunar High- lands Crust, 505 pp., Pergamon Press (1980) Geo- chim. -

Explore 12 Great Lunar Targets Sharpen Your Observing Skills on the Moon’S Craters, Lava Flows, and an Elusive Letter X

Small-scope wonders 11 7 Explore 12 great lunar targets Sharpen your observing skills on the Moon’s craters, lava flows, and an elusive letter X. 2 1 by Michael E. Bakich he Moon offers something for every observer. It has a face that’s always changing. Following it telescopically T through a lunar month can be fascinating. Ironically, when the Moon is brightest (Full Moon) is the worst time to view it. From our perspective, the Sun is shining on the Moon from a point directly behind us, minimizing shad- ows and thus revealing scant detail. 4 The best lunar viewing times are from when the thin cres- 5 cent becomes visible after New Moon until about 2 days after First Quarter (evening sky) and from about 2 days before Last Quarter to almost New Moon (morning sky). Shadows are lon- ger then, and features stand out in sharp relief. 8 This is especially true along the Moon’s shadow line — called the terminator — which divides the light and dark portions. Before Full Moon, the terminator shows where sunrise is occur- 12 ring; after Full Moon, it marks the sunset line. 6 10 Along the terminator, you’ll see mountaintops protruding high enough to catch sunlight while the dark lower terrain sur- rounds them. On large crater floors, you can follow “wall shad- ows” cast by sides of craters hundreds of feet high. All these 1 Archimedes Crater lies at 30° north latitude centered between the features seem to change in real time, and the differences you eastern and western limbs. -

List of Targets for the Lunar II Observing Program (PDF File)

Task or Task Description or Target Name Wood's Rükl Target LUNAR # 100 Atlas Catalog (chart) Create a sketch/map of the visible lunar surface: 1 Observe a Full Moon and sketch a large-scale (prominent features) L-1 map depicting the nearside; disk of visible surface should be drawn 2 at L-1 3 least 5-inches in diameter. Sketch itself should be created only by L-1 observing the Moon, but maps or guidebooks may be used when labeling sketched features. Label all maria, prominent craters, and major rays by the crater name they originated from. (Counts as 3 observations (OBSV): #1, #2 & #3) Observe these targets; provide brief descriptions: 4 Alpetragius 55 5 Arago 35 6 Arago Alpha & Arago Beta L-32 35 7 Aristarchus Plateau L-18 18 8 Baco L-55 74 9 Bailly L-37 71 10 Beer, Beer Catena & Feuillée 21 11 Bullialdus, Bullialdus A & Bullialdus B 53 12 Cassini, Cassini A & Cassini B 12 13 Cauchy, Cauchy Omega & Cauchy Tau L-48 36 14 Censorinus 47 15 Crüger 50 16 Dorsae Lister & Smirnov (A.K.A. Serpentine Ridge) L-33 24 17 Grimaldi Basin outer and inner rings L-36 39, etc. 18 Hainzel, Hainzel A & Hainzel C 63 19 Hercules, Hercules G, Hercules E 14 20 Hesiodus A L-81 54, 64 21 Hortensius dome field L-65 30 22 Julius Caesar 34 23 Kies 53 24 Kies Pi L-60 53 25 Lacus Mortis 14 26 Linne 23 27 Lamont L-53 35 28 Mairan 9 29 Mare Australe L-56 76 30 Mare Cognitum 42, etc. -

Glossary of Lunar Terminology

Glossary of Lunar Terminology albedo A measure of the reflectivity of the Moon's gabbro A coarse crystalline rock, often found in the visible surface. The Moon's albedo averages 0.07, which lunar highlands, containing plagioclase and pyroxene. means that its surface reflects, on average, 7% of the Anorthositic gabbros contain 65-78% calcium feldspar. light falling on it. gardening The process by which the Moon's surface is anorthosite A coarse-grained rock, largely composed of mixed with deeper layers, mainly as a result of meteor calcium feldspar, common on the Moon. itic bombardment. basalt A type of fine-grained volcanic rock containing ghost crater (ruined crater) The faint outline that remains the minerals pyroxene and plagioclase (calcium of a lunar crater that has been largely erased by some feldspar). Mare basalts are rich in iron and titanium, later action, usually lava flooding. while highland basalts are high in aluminum. glacis A gently sloping bank; an old term for the outer breccia A rock composed of a matrix oflarger, angular slope of a crater's walls. stony fragments and a finer, binding component. graben A sunken area between faults. caldera A type of volcanic crater formed primarily by a highlands The Moon's lighter-colored regions, which sinking of its floor rather than by the ejection of lava. are higher than their surroundings and thus not central peak A mountainous landform at or near the covered by dark lavas. Most highland features are the center of certain lunar craters, possibly formed by an rims or central peaks of impact sites. -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

Forest and Rangeland Soils of the United

Richard V. Pouyat Deborah S. Page-Dumroese Toral Patel-Weynand Linda H. Geiser Editors Forest and Rangeland Soils of the United States Under Changing Conditions A Comprehensive Science Synthesis Forest and Rangeland Soils of the United States Under Changing Conditions Richard V. Pouyat • Deborah S. Page-Dumroese Toral Patel-Weynand • Linda H. Geiser Editors Forest and Rangeland Soils of the United States Under Changing Conditions A Comprehensive Science Synthesis Editors Richard V. Pouyat Deborah S. Page-Dumroese Northern Research Station Rocky Mountain Research Station USDA Forest Service USDA Forest Service Newark, DE, USA Moscow, ID, USA Toral Patel-Weynand Linda H. Geiser Washington Office Washington Office USDA Forest Service USDA Forest Service Washington, DC, USA Washington, DC, USA ISBN 978-3-030-45215-5 ISBN 978-3-030-45216-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45216-2 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020 . This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. -

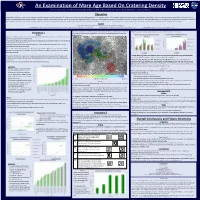

An Examination of Mare Age Based On

An Examination of Mare Age Based On Cratering Density The Chenango Forks Lunar Research Team: Sharon Hartzell, Jackson Haskell, Benjamin Daniels, Sarah Maximowicz, and Sarah Andrus Objective Cooled basaltic lava flows, known as maria, cover approximately sixteen percent of the lunar surface. The determination of absolute and relative ages of maria is an important question in lunar research, because it provides insight into the geologic history of the lunar environment. Many samples returned from the Apollo and Luna missions have been absolutely dated using radiogenic techniques. However, not all samples returned from the moon have been radiogenically dated. Furthermore, returned samples represent only a small portion of each visited mare. One of the major challenges facing lunar researches is the fact that most maria are still unvisited. The lack of complete data from visited maria in combination with the absence of data from unvisited maria has compelled lunar researchers to rely on remote techniques for relative dating. The overriding goal of our research was to develop and utilize a method for analyzing the ages of the twenty‐three lunar maria. Approach •Areas of the twenty‐three lunar maria were analyzed in three distinct investigations. Investigation 1: Total crater count to determine cratering densities, and comparison of densities to absolute age Investigation 2: Analysis of crater weathering in relation to age Investigation 3: Analysis of crater size in relation to age •A relative age map was created to display the distribution of the maria on the moon’s surface. The •Analysis of age dist ributions within individual mari a revealed several interesting trends: Investigation 1 map itself was obtained from Google Moon, and the maria were highlighted based on the scale Method displayed below.