Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian History Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Existing Challenges of Heritage

ACCESS Freely available online rism & OPEN ou H f T o o s l p a i t n a r l i u t y o J Journal of ISSN: 2167-0269 Tourism & Hospitality Research Article The Existing Challenges of Heritage Management in Gondar World Heritage Sites: A Case Study on Fasil Ghebbi and the Baths Shegalem Fekadu Mengstie* Department of History and Heritage Management, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia ABSTRACT Heritage management is an administrative means by which heritage resources are protected from natural and manmade cause of deterioration. The town of Gondar is located in Northwestern Ethiopia and it has outstanding and outstay world cultural heritage resources situated at its hub. However, these stunning properties are threatened with multidimensional heritage management problems. So, the main aim of this paper is to identify the main and existing challenges and show the severity of the problems in comparison with different case studies in the world. It compiled through qualitative research method with descriptive research design. And data were collected through survey, participant observation and photographic documentation and interpretation. The collected data also compiled by qualitative method of data analysis. The main and the existing challenges of Gondar’s world heritage sites, specifically of the Fasil Ghebbi and the baths are plant overgrowth, human activities on the immediate vicinity of the sites (that leads to vibration of the structures and noise disturbance), negligence, visitors pressure, improper conservation, nonexistence or inapplicability of heritage management plan, Lack of tourist follow-up system as a means for deliberate graffiti of heritages, lack of cooperation among the concerned bodies and unavailability of directions and instructions. -

Ethiopian Cultural Center in Belgium የኢትዮጵያ ባህል ማእከል በቤልጅየም

Ethiopian Cultural Center in Belgium የኢትዮጵያ ባህል ማእከል በቤልጅየም NEWSLETTERS ቁጥር –20 May 23, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS BRIEF HISTORY OF ETHIOPIA ¨/The Decline of Gondar and Zemene Mesafint PAGE 1-5 አጭር ግጥም ከሎሬት ጸጋዬ ገ/መድህን ገጽ 6 ሳምንታዊ የኮቪድ 19 መረጃ ገጽ 6-7 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Brief History of Ethiopia Part 10: The Decline of Gondar and The Zemene Mesafint (The Era of the Princes; 1769 – 1855) For about 200 years, Ethiopia passed through turmoil caused by the aggressiveness of the Muslim states, the far-reaching migrations of the Oromo and the disruptive influence of the Portuguese. These episodes left the empire much weakened andfragmented by the mid-seventeenth century. One result was the emergence of regional lords who are essentially independent of the throne, although in principle subject to it. In this issue of the newsletter, we will briefly describe the major events and decisive characters that shaped the course of Ethiopian history until the rise of Tewodros II in 1855. The Gondar period produced a flowering Indian textile and European furniture. of architecture and art that lasted for more Gondar enjoyed the veritable status of a than a century. For the 18 th century fashion capital to the extent that it was Ethiopian royal chroniclers, Gondar, as a described in the 1840s by two French city, was the first among the cities that captains as the “Paris de l’Abyssinie” fulfilled all desires. Imperial Gondar where ladies and gentlemen wore dresses thrived on war chests, trade and revenue of dazzling whiteness, had good taste, from feudal taxation. -

A Survey of Representative Land

1 A SURVEY OF REPRESENTATIVE LAND CHARTERS OF THE ETHIOPIAN EMPIRE (1314-1868) AND RELATED MARGINAL NOTES IN MANUSCRIPTS IN THE BRITISH LIBRARY, THE ROYAL LIBRARY AND THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES OF CAMBRIDGE AND MANCHESTER by Haddis Gehre-Meskel Thesis submitted to the University of London (School of Oriental and African Studies) for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 1992 ProQuest Number: 10672615 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672615 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 This work is humbly dedicated to the memory of His Grace Abune Yohannes, Archbishop of Aksum. ( 1897 - 1991 ) May his lifelong work in the service of the Ethiopian Church and people continue to bear fruit and multiply. 3 ABSTRACT The aim of this study is to compile and analyse information about ownership, sales and disputes of land in Ethiopia helween 1314 and 1868 on the basis of documents which are preserved in the marginalia of Ethiopia manuscripts in the Collections of the British Library, the Royal Library at Windsor Castle and the University Libraries of Cambridge and Manchester. -

The QUEST for the ARK of the COVENANT As This Book Was Going to Press the Publishers Received the Sad News of the Death of the Author, Stuart Munro- Hay

The QUEST for the ARK OF THE COVENANT As this book was going to press the Publishers received the sad news of the death of the author, Stuart Munro- Hay. It is their hope and expectation that this book will serve as a fitting tribute to his lifelong dedication to the study of Ethiopia and its people. The QUEST for the ARK OF THE COVENANT THE TRUE HISTORY OF THE TABLETS OF MOSES STUART MUNRO-HAY Published in 2005 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Website: http://www.ibtauris.com In the United States and Canada distributed by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © Dr Stuart Munro-Hay, 2005 The right of Stuart Munro-Hay to be identified as the author of this work has been assert- ed by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN 1-85043-668-1 EAN 978-185043-668-3 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress catalog card: available Typeset in Ehrhardt by Dexter Haven Associates Ltd, London Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin Contents Preface and Acknowledgements . -

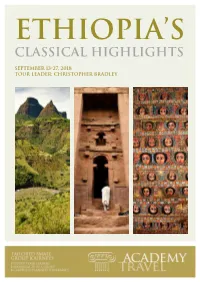

Classical Highlights

E THIOPIA ’S CLASSICAL HIGHLIGHTS SEPTEMBER 13-27, 2018 TOUR LEADER: CHRISTOPHER BRADLEY ETHIOPIA’S CLASSICAL Overview HIGHLIGHTS From the Queen of Sheba to the rule of Emperor Haile Selassie in the Tour dates: September 13-27, 2018 20th century, Ethiopia has carved out for itself a unique identity among African nations. It was one of the first Christian countries in the world and Tour leader: Christopher Bradley still has a Christian majority. This classic itinerary has been devised for travellers to witness the remarkable legacy of Ethiopia's unique history. Tour Price: $8,435 per person, twin share Our tour moves in a circle from the capital, Addis Ababa. Our first stop is Single Supplement: $1,180 for sole use of Bahar Dar, close to the source of the Blue Nile, where we visit Lake Tana double room and the Tississat Falls. At Gondar, the 18th and 19th-century capital, we visit an amazing series of castles and palaces. Continuing towards Axum, Booking deposit: $500 per person we spend a night in the spectacular Simien Mountains and bushwalk in the national park. We visit archaeological sites in the ancient capital of Recommended airlines: Emirates Axum that was home to the Queen of Sheba and, reputedly, the Ark of the Covenant. Our final stop is the spectacular rock-cut churches of Lalibela, Maximum places: 20 one thousand years old and truly world-class sites, before our return to Addis Ababa. Itinerary: Addis Ababa (3 nights), Bahar Dar (2 nights), Gondar (2 nights), Simien Mountains (1 Ethiopia is not a well-developed travel destination. -

City Profile Gondar

SES Social Inclusion and Energy Managment for Informal Urban Settlements CITY PROFILE GONDAR Atsede D. Tegegne, Mikyas A. Negewo, Meseret K. Desta, Kumela G. Nedessa, Hone M. Belaye CITY PROFILE GONDAR Atsede D. Tegegne, Mikyas A. Negewo, Meseret K. Desta, Kumela G. Nedessa, Hone M. Belaye Funded by the Erasmus+ program of the European Union The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. The views expressed in this work and the accuracy of its findings is matters for the author and do not necessarily represent the views of or confer liability on the Center of Urban Equity. © University of Gondar. This work is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 2 CITY PROFILE GONDAR CONTENTS PART 1 Introduction 4 PART 2 History and Physical Environment of Gondar 6 2.1 Historical Development 7 2.2 Physical Environment 9 PART 3 Economy and labor markets 12 PART 4 Demographic growth and migration 15 4.1 Population size and growth 15 4.2 Fertility and Mortality levels 15 4.3 Migration 15 4.4 Age-Sex composition 16 PART 5 Spatial distribution of informal settlements PART 6 Future development plan 19 6.1 An Overview of the Gondar City Plan 19 6.2 Proposed interventions 21 6.3 Structural Elements of the Land use 23 6.4 City-region, long-term boundary and development frame of Gondar city 23 6.5 Synthesis of the plan 25 References 28 3 CITY PROFILE GONDAR PART 1 INTRODUCTION The city of Gondar is situated in North-western the least to its GDP (only 7%) but also generates a parts of Ethiopia, Amhara Regional State. -

Land Tenure and Agrarian Social Structure in Ethiopia, 1636-1900

LAND TENURE AND AGRARIAN SOCIAL STRUCTURE IN ETHIOPIA, 1636-1900 BY HABTAMU MENGISTIE TEGEGNE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2011 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Emeritus Donald Crummey, Chair Associate Professor Carol Symes Professor Emeritus Charles Stewart Assistant Professor James Brennan Associate Professor Kenneth Cuno Abstract Most scholars have viewed property in pre-modern Ethiopia in ―feudal‖ terms analogous to medieval Europe. According to them, Ethiopia‘s past property arrangement had been in every respect archaic implying less than complete property rights, for, unlike in modern liberal societies, it vested no ownership or ―absolute‖ rights in a single individual over a material object. By draining any notions of ownership right, historians therefore characterized the forms of property through which the Ethiopian elites supported themselves as ―fief-holding‖ or rights of lordship, which merely entitled them to collect tribute from the subject peasantry. By using land registers, surveys, charters, and private property transactions, which I collected from Ethiopian churches and monasteries, this dissertation challenges this conception of property in premodern Ethiopia by arguing that Ethiopian elites did exercise ownership rights over the land, thus providing them a means by which to control the peasantry. Through the concepts of rim (a form of private property in land exclusively held by social elites) and zéga (a hitherto unrecognized serf-like laborers), I explore the economic and social relationship between rulers and ruled that defined political culture in premodern Ethiopia. -

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 2012 E.C (2019/20) Academic Year Third Quarter History Handout 4 for Grade 11 Students

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 2012 E.C (2019/20) Academic year Third Quarter History Handout 4 for Grade 11 Students Dear students! This handout is prepared to acquaint you with the history of Ethiopia from the seventeenth century until the middle of the nineteenth century. It can be said that it is a sequel of the previous chapter that deals with the major events of the sixteenth century. As such, this handout treats such events as the Catholics encounter, the Gondar period and the momentous period of the Zemene Mesafint or the Era of Princes. My beloved Students! Take caution and keep yourself and your family from the Coronavirus. Since you are the sons and daughters of the country and of course, heirs of the current generation, your motherland, above all things, needs your health and survival. I have a great hope that we will reunite as soon as the existing situation reversed and things return to normal. Unit 9 The Ethiopian Christian Highland Kingdom (1543-1855) 9.1. Catholicization and Civil wars The Portuguese soldiers, who helped the Christian kingdom to gain victory over the Adal Muslim Sultanate, remained in Ethiopia. Other Portuguese Catholic missionaries who know under the name Jesuits or the Society of Jesus came to preach Catholicism in Ethiopia in 1557. The aim of the Jesuits was to convert the people into Catholicism. As a preliminary to this, they strove to convert the Christian kings into Catholicism. It was at first emperor Gelawdewos whom the Jesuits tried to convert but they failed to do so due to the emperor’s unwillingness. -

Local History of Ethiopia : Naader

Local History of Ethiopia Naader - Neguz © Bernhard Lindahl (2005) HFE24 Naader, see Nadir HEL27 Naakuto Laab (Na'akuto La'ab, Na'akweto L.) 12/39 [+ x Pa] (Nakutalapa, Nekutoleab) 2263 m 12/39 [Br n] (cave church), see under Lalibela HFF21 Naalet (Na'alet) 13°44'/39°25' 1867 m 13/39 [Gu Gz] north-west of Mekele Coordinates would give map code HFF10 HEK21 Nabaga, see Nabega H.... Nabara sub-district (centre in 1964 = Limzameg) 10/37? [Ad] HEK21 Nabega (Nabaga, Navaga) 11°59'/37°37' 1786 m 11/37 [Gz WO Gu Ch] (Navaga Ghiorghis, Nabaga Giyorgis) at the east shore of lake Tana HDH09 Nacamte, see Nekemte JCN14 Nacchie 07°23'/40°10' 2079 m 07/40 [WO Gz 20] HDD10 Nacha 08°18'/37°33' 1523 m, north of Abelti 08/37 [Gz] HDM.. Nachage (district in Tegulet) 09/39 [n] JEA24 Nachir (Naccir) (area) 11/40 [+ WO] HDL63 Nachire 09°41'/38°46' 2581 m, south of Fiche 09/38 [AA Gz] HDL28 Nachiri 09°18'/39°09' 2810 m 09/39 [Gz] between Sendafa and Sheno HCC17 Nacille, see Mashile HBP62 Nacua, see Nakua HCR47 Nada (Nadda) 07°36'/37°13' 1975 m, east of Jimma 07/37 [Gz Mi WO Gu] 500 m beyond the crossing of the Gibie river on the main road to Jimma, a trail to the right of the road for 10 km traverses the entire plain of Nada up to the edge of the mountainous May Gudo massif. [Mineral 1966] HCF01 Nadara, see Nuara HED06 Nadatra, see Nedratra nadda: nadde (O) woman; wife; nedda (nädda) (A) drive /herd to pasture/; nada (A) landslide; nade (nadä) (A) make to collapse HCR47 Nadda, see Nada HCR48 Nadda (area) 07/37 [WO] HCD13 Naddale, see Maddale HER48 Nadir (Nader, Amba Nadir) 13°03'/37°19' 1286 m 13/38 [WO Gu Ad Gz] (mountain), in Aksum awraja HFE24 Nadir (Naader, Nader) 13°49'/38°49' 1330 m 13/38 [Gz] north-west of Abiy Adi HFE38 Nadir 13°55'/39°14' 1670 m, north-east of Abiy Adi 13/38 [Gz] /which Nadir (Nader)?:/ May Tringay primary school (in Aksum awraja) in 1968 had 56 boys and 18 girls in grades 1-5, with 2 teachers. -

Power, Church and the Gult System in Gojjam, Ethiopia

Power, Church and the Gult System in Gojjam, Ethiopia POWER, CHURCH AND THE GULT SYSTEM IN GOJJAM, ETHIOPIA Temesgen Gebeyehu BAYE Bahir Dar University, Faculty of Social Sciences Department of History POB: 2190, Ethiopia [email protected] Since the introduction of Christianity to Ethiopia, there had been an interdependence between the state and the church. Both parties benefited from this state of affairs. The Orthodox Church played as the ideological arm of the state. The king became head not only of the state, but also of the church. The church enjoyed royal protection and patronage, ranging in concrete terms like the granting of land, called the gult system. The gult system was an important economic institution and connection between the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and the state. The system was essentially a political and economic relations between the state, the church and the cultivators. It not only included tribute and administrative rights, but also entailed direct control over land. In the Ethiopian academics, the issue of the gult system has been treated and examined in its totality. There is an evident gap in our knowledge of the dynamics of the gult system and its ideological, administrative, political and economic implications. This paper, based on published and unpublished materials, examines the dynamics of gult, state and church relations intersectionally. It attempts to identify changes and continuities in the basic pattern of relations and a variety of institutional linkages. To this end, a great deal of archive collections on Gojjam Governorate General from the Ethiopian National Archives and Library Agency has been consulted and reviewed to add new and useful insights and understandings on relations and interests between the cultivators, the church and state. -

Etiopia Storica 2018 Appunti Di Viaggio

Inverno 2018 1 - 94 Etiopia Storica 2872 Etiopia Storica 2018 Appunti di viaggio Non tutti i luoghi riportati saranno visitati - Proprietà Avventure nel Mondo Etiopia Storica 2872 2 - 94 Inverno 201 In Xanadu did Kubla Khan A stately pleasure-dome decree : Where Alph, the sacred river, ran Through caverns measureless to man Down to a sunless sea. Samuel Taylor Coleridge: Kubla Khan, or, A Vision in i Dream. Ultimo salvataggio: 02/12/2018 19.24.00 Stampato in proprio: 02/12/2018 19.24.00 Autore: Marco Vasta File: C:\CONDIVISA\Marco\Viaggi\2018\Ethiopia\Qdv Estratto Ethiopia LP 5.Doc Revisione n° 54 Le strade avanzano, le montagne si muovono. Curatore, autore ed editore non si assu- mono alcuna responsabilità per le informazioni presentate a solo scopo di crescita cultu- rale. Le informazioni sono fornite “così come sono” ed in nessun caso autore ed editore sa- ranno responsabili per qualsiasi tipo di danno da frustrazione, incluso, senza limitazioni, danni risultanti dalla perdita di beni, profitti e redditi, valore biologico, dal costo di ripri- stino, di sostituzione, od altri costi similari o qualsiasi speciale, incidentale o consequen- ziale danno anche solo ipoteticamente collegabile all'uso delle presenti informazioni. Le presenti informazioni sono state redatte con la massima perizia possibile in ragione dello stato dell'arte delle conoscenze e delle tecnologie; la loro accuratezza e la loro affi- dabilità non è comunque garantita in alcun modo e forma da parte del curatore, né di alcuno. Proprietà Avventure nel Mondo Inverno 2018 -

Tour Name Historic Ethiopia Cultural Expedition Arrival P/U Bole Airport, Addis Ababa Departure D/O Bole Airport, Addis Ababa

Tour Name Historic Ethiopia Cultural Expedition Arrival P/U Bole Airport, Addis Ababa Departure D/O Bole Airport, Addis Ababa Itinerary at a glance Day Location Accommodation MealPlan 1 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Sheraton Hotel LDBB 2 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Sheraton Hotel LDBB 3 Lalibela Tukul Village LDBB 4 Lalibela Tukul Village LDBB 5 Simien Mountains NPark Simien Lodge L-DBBL 6 Simien Mountains NPark Simien Lodge DBBL 7 Bahir Dar / Lake Tana Kuriftu Resort & Spa DBBL 8 Bahir Dar / Lake Tana Kuriftu Resort & Spa DBBL 9 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia L-Lunch, D-Dinner, BB-Bed and breakfast, LDBB-Lunch, dinner, bed and breakfast. Game drives & activities at the discretion of guide. Day by Day Itinerary Day 1 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Met at Bole airport and transferred by private vehicle Sheraton Hotel-Executive room LDBB Day 2 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Full day in Addis. Sightseeing is available should time permit. The rich culture of Ethiopia, and it's international links, has endowed the city with many fine restaurants and street side cafe's. Nightlife, including many cinemas, traditional dancing houses, casino's and bars provide entertainment until the early hours. We start out day by driving north up to Mount Entoto. In 1881 Emperor Menelik II made his permanent camp there, after remains of an old town (believed to have been the capital of 16th century monarch Lebna Dengel) were discovered, which Menelik took was a divine and auspicious sign. Addis Ababa at between 2300 - 2500 meters is the third highest capital in the world and Entoto is a few hundred meters higher - as we drive up the hill there is an appreciable drop in temperature and the air is filled with the scent of the Eucalyptus trees which line the road.