Inspiring Elite Action for a More Just Society?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Namibia Voter Education Proj Ect October 15 - December 15, 1992

Final Report: The Namibia Voter Education Proj ect October 15 - December 15, 1992 ..... The National Democratic. Institute for International Affairs in cooperation with the Namibian Broadcasting Corporation NATIONAL DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS • FAX (202) 939·3166 Suite 503,1717 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C 20036 (202) 328'3136 • Telex 5106015068 NDlIA This report was drafted by Sean Kelly, the representative of the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI) in Namibia. Mr. Kelly served as an advisor to the Namibian J3roadcasting Corporation during the voter education project that began October 15 and continued until December 15, 1992. conducting nonpartisan international programs to help maintain and str81lgth81l democratic institutions ~" TABLE OF CONTENTS I. SUlVIMARY . .. 1 ll. BACKGROUND . .. 1 The 1992 Regional and Local Elections'in Namibia . .. 1 The Official U. S. View .,. .. 2 m. THE NDI-NBC VOTER EDUCATION PROJECT. .. 3 NDl's Functional Expertise . .. 3 NDl's Program in Namibia . .. 3 NBC as a Channel to the Namibian Voter . .. 4 Guidelines for 'NDI-NBC Cooperation ........................... 4 How the Project Worked .............. " . .. 5 Election Programming . .. 7 The Role of the Political Parties . .. 8 IV. CONCLUSION........................................ 9 APPENDICES I. Sampling of Advertisements in Namibian press for NBC programs II. NBC Voter Education Program Final Report ill. NDI-NBC Radio Drama "We Are Going to the Polls" I. SUMMARY From October 15 to December 15, 1992, the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NO!) conducted a voter education project in Namibia through a cooperative agreement with the Namibian Broadcasting Corporation (NBC). The project's goal was both educational and motivational -- to inform Namibians about the process and purpose of the 1992 Regional and Local Elections and to motivate them to participate by registering to vote and, ultimately, to cast their ballots. -

OOLWORTHS Yesterday It Emerged That the Public Service ADDING QUALITY to Commission Has Yet to LIFE

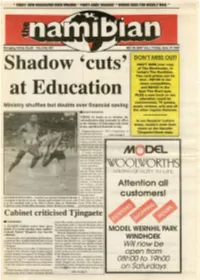

* ,TODAY: NEW MASSACRES ROCK RWANDA ft PARR-GOER 'BRAAIED' *'· MODISE GOES FOR WEEKLY MAIL * Bringing Africa South Vol.3 No.427 N$1.50 (GST Inc.) Friday Jun_e 10 1994 DON'T MISS OUT! DON'T MISS your copy Shadow 'cuts' of The Weekender, in today's The Namlblan. Two cash prizes can be won· N$100 in our chess competition, and N$150 In the Spot The Word quiz. at Education PLUS a new book on sex education could be controversial, TV guides, Ministry shuffles but doubts over financial saving music reviews, arts and all _ the other regular features • • STAFF REPORTER THERE IS doubt as to whether the **************** rationalisation plan currently in effect In our Readers' Letters in the Ministry of Education will result today, readers state their in any significant financial saving. views on the Garoebl It appears that most of PSC's Department of Tjingaele/Unam saga. the affected staff are be- cont. on page 2 ingtransferredintolower .----.:=:.:::.:..!:~:...:.._-L:::::::==============~ posts while keeping their existing benefits. Most of the posts are also said to be vacant and not budgeted for this year. A weekly newspaper M f~I..... )~CL claimed this week that the restructuring will re sult in a 30 per cent re duction in the Ministry's annual expenditure. OOLWORTHS Yesterday it emerged that the Public Service ADDING QUALITY TO Commission has yet to LIFE. approve the rationalisa- tion proposal for the Ministry of Education and Culture, despite Attention all scores of officials receiv ing letters informing them of their new posi tions this week. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42685-5 — Media, Conflict, and the State in Africa Nicole Stremlau Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42685-5 — Media, Conflict, and the State in Africa Nicole Stremlau Index More Information Index Addis Reporter, 27 print media culture, 23–25 Addis Zemen newspaper, 26, 28, 64, 71, 81, 142 Uganda, 19–21 Afeworki, Isaias, 5 autocratic government, 1, 63 African Development Bank, 42 autonomy, defined, 63 African National Congress (ANC), 8, 101 African Pilot, 31 Ba’ath party, 114 African Power and Politics Programme, 8 baitos (people’s councils), 49, 56 Afrobarometer, 4, 20 Bantu group, 22 Agena, Sissay, 82–83 Barifa newspaper, 71 Ahmara National Democratic Movement Berhana Salem printing press, 25 (ANDM), 57 Berhe, Aregawi, 48–49, 53 Al Alam newspaper, 71 Berlin Wall, 52, 65 Albania, 52 Besigye, Kizza, 19–20, 137, 143 Albright, Madeline, 5 Bezabih, Mairegu, 82 Ali, Moses, 114 Bharti Airtel, 126 All Amhara Peoples’ Organization (AAPO), 58 Biafran War in Nigeria, 32 American Civil Rights Movement, 9 Bitek, James Oketch, 137 American Embassy, 27 blogs/blogging Amhara group, 22, 46, 57 blocking of, 17 Amhara-Tigre supremacy, 43 criticism of EPRDF, 92 Amin, Idi, 5, 33–36, 101 political information from, 63 Amnesty International Special Award for Human professionalisation and, 123 Rights Journalism under Threat, 151 Zone 9 blogging collective, 16, 69–70, 95 anti-establishment coverage, 131–132 Blumler, Jay, 37 anti-peace groups, 16, 77 Buganda Government, 30–31 anti-terrorism legislation, 88 Bukedde newspaper, 21 Anti-Terrorism Proclamation (2009), 94 Business Process Re-Engineering (BPR), 64 Aregawi, Amare, -

Conflict Management in Anticipation of Them Acting As Facilitators of the Peace Process in Sudan

CCORD SEMI-ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE PERIOD 01 APRIL TO 30 SEPTEMBER 99 SUBMITTED TO USAID , ~ '~ ,',< CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 1 EDUCATION AND TRAINING UNIT ....................................................................................................... 3 COMMUNICATION AND INFORM ATION .......................................................................................... 11 PUBLIC SECTOR UNIT ............................................................................................................................ 16 PEACEKEEPING UNIT ............................................................................................................................ 22 RESEARCH UNIT ...................................................................................................................................... 56 ACCORD RURAL OFFICE ...................................................................................................................... 60 ACTIVITIES IN THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR'S OFFICE: ............................................................. 65 FINANCIAL STATEMENT ...................................................................................................................... 71 I I I 1. EXECUTIIIE SUMMARY I I This semi-annual report comes at a time when we at ACCORD have completed our first phase in the consolidation process, which commenced in 1997. We are happy to report that the systems -

REPORT UNITED NATIONS COUNCIL for Nal\1IBIA

""'~'~'-_ -.--.~.~._--_.~._-~,-~ ~ ~_.~-.",-,~-~,",,-,_.~_ ~ ,-~ -"""-~'--'~~"~:-'~'~-~-::~:::;-~.:,,~="_~~~~::-=-'::"::==::-:::",:':-~--'-':.- ~~ ~~._-~.>~--~----~--==.:.:-.::~~~::.~:;--T:~;:~"~.::~~=,:::""~:-:.:~':,.,._:'7:-:::::',::J=:~~:.~::~=::':;'¡f:.~~~~;~~i";¡~~- -.-~...".....,-•..• _ _~ ,.~ _.•~~..•.,,_ •. , ,,__~~ " ••••'.·•._,T,~....• _""•• __,_.•,._ _. ~~ _._ .... ... .< W-'" .. .. ',_" , REPORT OF THE UNITED NATIONS COUNCIL FOR NAl\1IBIA VOLUME 1 GENERAL ASSEMBLV 'OFFIGIAL RECORDS: TWENTY-NINTH SESSION SUPPLEMENT No. 24 IA/96'241) ¡ :1 ,í í" \ UNITED NATIONS p. ) REPORT OF THE I UNITED NATIONS COUNCIL \ ¡ , FOR NAMIBIA, VOLUME 1 '1 ¡, GENERAL ASSEMBLV OFFICIAL RECORDS: TWENTY-NINTH SESSION SUPPLEMENT No. 24 (A/9624) UNITED NATIONS New York, 1974 I 'J I' LETTER O) INTRODUC~ PART ONE NOTE l. POL: Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capitalletters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations documento A. The present volume contains the report of the United Nations Council for Namibia I'j B. covering the period from 2S September 1973 to 16 August 1974. Annexes 1to VII to the i! report appear in volume 11. An addendum to the report, covering the period from 17 August to 11 October 1974, appears inSupplement No. 24A (A/9624/Add.l). C. 11. ACT: CON: A. B. c. 111. LEG A. B. PART TWO l. EXPI PRE A. B. C. D. LOrigin~l: Eng1ish7 A~ I :'; II. 11 l.! t CONTENTS I ~{ A. "1 I Pr.rarrephs Pare f 1 B. vi LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL • • • • •• •• ••• • •• •• • • · . ... • • • C. INTRODUCTION . ...... ... ~ . • • • • 1 - 6 1 III. AC PART ONE: SITUATION IN NAMIBIA '1 A. 1. POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS •• • • •• •• • • •• 7 98 2 · . · .. 1 B. A. General political situation •.•.•.••.•• o 7 - 16 2 B. -

General Assembly

UNITED NATIONS Distr. GENERAL GENERAL A/9725-r ~' \ . ASSEMBLY 12 September 1974 · • ORIGINAL: ENGLISH Twenty-ninth session Item 66 (d) of the provisionel agenda* QUESTION OF NAMIBIA United Nations Fund for Namibia Report of the Secretary-General CONTENTS Paragraphs Page I. INTROLUCTION • . l - 12 2 II. OPERATION OF THE FUND. 13 - 26 4 Ill. CO-OPERATION WITH OTHER PROGRAMMES 27 - 28 6 IV. ADVISORY BODY. -. 29 - 33 7 v. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS. 34 - 40 8 ANNEX VOLUNTARY CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE UNITED NATIONS FUND FOR NAMIBIA RECEIVED UP TO l SEPTEMBER 1974 * A/9700. 74-24070 I . .. A/9725 English Page 2 I. INTRODUCTION 1. By resolution 2679 (XXV) of 9 December 1970, the General Assembly decided to establish a United Nations Fund for Namibia. The decision was premised on the consideration that the United Nations, having terminated South Africa's mandate to administer Namibia and having itself assumed direct responsibility for Namibia until independence, had incurred a solemn obligation to assist and prepare the people of Namibia for independence and that to this end the United Nations should provide them with comprehensive assistance. 2. The Assembly's decision was taken after consideration of a request by the Security· Council, contained in its resolution 283 (1970) of 29 July 1970, that a fund should be created to provide assistance to Namibians who had' suffered from p~rsecution and to finance a comprehensive educational training programme for Namibians, with particular regard to their future administrative responsibilities in the Territory. 3. Having taken a decision of principle upon the establishment of the Fund, the Assembly, in paragraph 5 of resolution 2679 (XXV), deferred the decision on the extent of the financial implications pending receipt at its twenty-sixth session of a report to be prepared by the Secretary-General. -

Onetouch 4.0 Sanned Documents

Confidential NAMIBIAN REVIEW: MARCH 2005 Confidential A BRIEF POLITICAL OVERVIEW AND CURRENT ASSESSMENT OF DIAMOND DEVELOPMENTS IN NAMIBIA 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The recent elections in Namibia saw the ruling South West African Peoples Organisation (Swapo) swept back into power with the same number of seats as the previous election in 1999. With the new presidential candidate Hifikepunye Lukas Pohamba only being inaugurated on 24 March, continuity of policy on all levels is more or less expected, given the fact that Pohamba was hand-chosen by outgoing president Sam Nujoma to replace him. Potential rivals for the Swapo presidency were dealt with in the months leading up to the elections. This included specifically Hidipo Hamutenya, once one of Swapo's favourite sons, who was unceremoniously dumped as foreign minister by Nujoma in May 2004 just days before the Swapo Congress to choose Nujoma's successor. Though defeated, Hamutenya's background and support base in amongst people _ who were part of Swapo's Peoples Uberation Army of Namibia (Plan), will ensure that he emerges once again as Pohamba's chief challenger for the position in five years time. The opposition remains weak and in general disarray with the once powerful Democratic Turnhalle Alliance (DTA) , having lost nearly half the parliamentary seats it had prior to the last elections. As far as developments on the diamond front are concerned the report makes the following broad points: • Continuity in the government's diamond policy can be expected under Pohamba. • Lev Leviev has been the driving force behind changes in Namibia's mining legislation in 1999 and further changes being contemplated for the near future. -

REGISTRATUR AA. 3 (Enlarged and Revised Edition)

REGISTRATUR AA. 3 (Enlarged and Revised Edition) 2 REGISTRATUR AA. 3 (Enlarged and Revised Edition) GUIDE TO THE SWAPO COLLECTION IN THE BASLER AFRIKA BIBLIOGRAPHIEN Compiled by Giorgio Miescher Published by Basler Afrika Bibliographien Namibia Resource Centre & Southern Africa Library 2006 3 © 2006 Basler Afrika Bibliographien Publisher: Basler Afrika Bibliographien P.O.Box 2037 CH 4001 Basel Switzerland http://www.baslerafrika.ch All rights reserved Printed by Typoprint (Pty) Ltd, Windhoek, Republic of Namibia ISBN 3-905141-89-2 4 List of Contents I The General Archives of the Basler Afrika Bibliographien 7 II Introduction to the enlarged and revised edition 9 Changing archiving pattern since 1994 10 Collections of SWAPO material scattered around the world 12 The BAB SWAPO collection and its institutional context 14 Researching the history of SWAPO (and the liberation struggle) 16 Sources to write the history of SWAPO and the liberation struggle 20 III How to work with this Archival Guide 22 Structure of organisation 22 Classification system of the SWAPO collection 22 List of abbreviations 24 IV Inventory AA. 3 25 before 1966 from SWAPO 27 1966 about SWAPO 28 1968 from SWAPO 29 1969 from/about SWAPO 30 1970 from/about SWAPO 32 1971 from/about SWAPO 34 1972 from/about SWAPO 37 1973 from/about SWAPO 42 1974 from/about SWAPO 45 1975 from/about SWAPO 50 1976 from/about SWAPO 56 1977 from/about SWAPO 64 1978 from/about SWAPO 72 1979 from/about SWAPO 82 1980 from/about SWAPO 88 1981 from/about SWAPO 100 1982 from/about SWAPO 113 1983 from/about -

1965-1988 Prof Peter Hitjitevi Katjavivi: 1941

Katjavivi, PH PA 1 THE KATJAVIVI COLLECTION: 1965-1988 PROF PETER HITJITEVI KATJAVIVI: 1941 - Historical Background Professor Peter Katjavivi was born on 12 May 1941 in Okahandja, Namibia. He travelled into exile in 1966 and was part of the Dar es Salaam exiles that helped transform SWAPO into an international force in the struggle for the liberation of Namibia. Until 1979 he was a fulltime SWAPO activist running the London office and holding the movement’s Information and Publicity post. From the 1980s, he pursued his academic career which saw him gaining a Master’s degree in 1980 from the University of Warwick, UK and a Doctor of Philosophy in1986 from St Anthony’s College, University of Oxford. In 1989, he was elected to the Constituent Assembly and served as National Assembly member until 1991. In 1992 he was named the first Vice-Chancellor of the University of Namibia, a post he held for eleven years. He was appointed as Professor in History by the UNAM Academic Council Staff Appointments Committee in 1994. He was given a diplomatic posting in 2003. Peter Katjavivi has also been very active as SWAPO’s documenter of the liberation struggle. His book, ‘A History of Resistance in Namibia’ (James Currey, 1988) is still widely referred to in academic works on recent Namibian history. Currently, he is the Director-General of the National Planning Commission. THE COLLECTION Summary The collection, covering the period 1965 to 1988 (but also holding some documents from as far back as 1915) consists mainly of SWAPO documents on activities in and outside Namibia during the time for the struggle for the liberation of Namibia (See summary of classes below). -

Boo19870300.043.027.Pdf

LIST OF CONTENTS Editorial 1 New Year Message to the Namibian People 2 Tribute to Olof Palme a Friend in Need and in Deed 7 Cde. Enerst Kadungure calls for Solidarity in fight against Apartheid 9 Liberation Struggle will continue in Namibia 11 The Lutherans Re-affirm commitment to the Namibians 12 International Women's Day 14 SWAPO denounces S .A. Killer Squad in Namibia 15 SWAPO studies white Namibians' proposals to break Impasse 16 Workers must demand May Day to be a Public Holiday 17 Isolate Pretoria Finnish People's Assembly 18 Book donation to SWAPO 19 Home N ews: Racist South Africa Koevoet Police harass SWAPO President's Mother 20 Escalation of Detentions in Namibia 21 News from the Battlefield 23 POEM 27 SWAPO National Anthem 28 Published by SWAPO Foreign Mission in Zimbabwe P .O . Box CR 2 Telephone 795342 Cranborne Telex 2625 ZW Typeset and printed by Jongwe Printing and Publishing Company (Pvt .) Ltd SWAPO News and Views, January-March 1987 1 EDITORIAL UDI FOR NAMIBIA IS A DEAD-END STREET The South African appointed "interim Thus, the only thing that the puppets will government" in Namibia announced on succeed to achieve by this absurd preten- February 13, 1987 that it intends to move tion is to assume even more the burden of towards a greater degree of formal sharing with Pretoria the unenviable autonomy from South Africa by creating responsibility for the countless atrocities two additional "ministries," one for inter- which the South African army of occupa- nal security and the other for international tion is daily committing in its desperate ef- co-operation, and by adopting a range of fort to cow the Namibian people into sovereign state paraphernalia . -

South West Africa (Namibia)

---------------------------------------Country profile South West Africa (Namibia) South West Africa (SWA) or Namibia has been adminis by the International Court of Justice in 1950, 1955, 1956 and tered by South Africa since South African forces occupied 1966 was that the mandate continued to exist and although the territory in 1915 at the request of the Allied Powers in the South African government was under no obligation to World War I. Prior to the invasion, SWA had been under enter into a trusteeship agreement with the UN, South Africa German rule for more than three decades. was not competent to alter the international status of the The German presence dated from 1883 when Heinrich territory unilaterally. Since 1966 the UN has adopted various Vogelsang, acting on behalf of the merchant LOderitz, resolutions declaring the mandate terminated and requesting bought some land bordering on the historic bay of Angra member states to refrain from actions that would imply recog Pequena from the Oorlams Nama at Bethanien. It was later nition of South Africa's authority over l\Jamibia. A reconsti renamed LOderitzbucht. This was followed by the declaration tuted International Court of Justice in 1971 ruled in favour of of a German protectorate over the interior in 1884. German the UN view that South Africa's presence in Namibia was SWA, however, did not include Walvis Bay and the Penguin illegal. Islands which had been annexed by Britain for the period The UN also established a UN Council for l\Jamibia as well 1861 to 1878 and incorporated into the Cape Colony in 1884. -

Question of Namibia - UN Organs and Sponsored Activities - United Nations Commissioner for Namibia

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 187 Date 06/06/2006 Time 11:29:30 AM S-0902-0009-01 -00001 Expanded Number S-0902-0009-01 -00001 Title items-in-Africa - Question of Namibia - UN organs and sponsored activities - United Nations Commissioner for Namibia Date Created 28/01/1976 Record Type Archival Item Container s-0902-0009: Peacekeeping - Africa 1963-1981 Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit w UN/TED NAT/ONS Distr. G tF_ IN N LF_ IRX /A^ l1_ ./S&^P^V GENERAL C C C M Q 8 V WCW^/M A/31A65 A b b t M D L Y W^^f 21 December 1976 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH Thirty-first session Agenda item 85 (d) QUESTION OF NAMIBIA Appointment of the United Nations Commissioner for Namibia Note by the Secretary-General 1. At its 2205th plenary meeting, on 18 December 1973, the General Assembly, on the proposal of the Secretary-General (A/9^65), appointed Mr. Sean MacBride as United Nations Commissioner for Namibia for a period of one year, with effect from 1 January 197^. At its 23l8th and 2Ul9th plenary meetings, on 13 December 197^ and 26 November 1975 3 the General Assembly, on the proposal of the Secretary-General (A/9863 and A/10382), approved the extension of the appointment of Mr. MacBride for two one-year terms until 31 December 1975 and 31 December 1976, respectively. I 2. Having completed the necessary consultations, the Secretary-General wishes to propose to the General Assembly, for its approval, the appointment of Mr,.