Rakhine State Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015 This document is published by the Center for Diversity and National Harmony with the support of the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund. Publisher : Center for Diversity and National Harmony No. 11, Shweli Street, Kamayut Township, Yangon. Offset : Public ation Date : September 2015 © All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Rakhine State, one of the poorest regions in Myanmar, has been plagued by communal problems since the turn of the 20th century which, coupled with protracted underdevelopment, have kept residents in a state of dire need. This regrettable situation was compounded from 2012 to 2014, when violent communal riots between members of the Muslim and Rakhine communities erupted in various parts of the state. Since the middle of 2012, the Myanmar government, international organisations and non-governmen- tal organisations (NGOs) have been involved in providing humanitarian assistance to internally dis- placed and conflict-affected persons, undertaking development projects and conflict prevention activ- ities. Despite these efforts, tensions between the two communities remain a source of great concern, and many in the international community continue to view the Rakhine issue as the biggest stumbling block in Myanmar’s reform process. The persistence of communal tensions signaled a need to address one of the root causes of conflict: crushing poverty. However, even as various stakeholders have attempted to restore normalcy in the state, they have done so without a comprehensive needs assessment to guide them. In an attempt to fill this gap, the Center for Diversity and National Harmony (CDNH) undertook the task of developing a source of baseline information on Rakhine State, which all stakeholders can draw on when providing humanitarian and development assistance as well as when working on conflict prevention in the state. -

Remaking Rakhine State

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

Malteser MCH-PHC-WASH Activities in Maungdaw Township Rakhine State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Malteser MCH-PHC-WASH Activities in Maungdaw Township Rakhine State 92°10'E 92°20'E 92°30'E Chin Mandalay PALETWA BANGLADESH Ü Rakhine Magway Baw Tu Lar In Tu Lar Bago Tat Chaung Myo Naw Yar Hpar Zay Dar A®vung Tha Pyay San Su Ri Ayeyarwady Kar Lar Day Hpet N N ' ' 0 0 2 !< Myo (Ye Aung Chaung) 2 ° ° 1 Kyaung Toe Mar Zay 1 2 !< !< 2 Bwin (Baung)!< Aung Zan !< Gu Mi Yar Shee Dar !< Ye Aung San Ya Bway V# !< Kyaung Na Hpay (Myo) Kaung Na Phay Ah Nauk Tan Chaung Gaw Yan Ywa Tone Chaung !< !< #0 Ah Shey Htan Chaung (Htan Kar Li) Taing Bin Gar !< !< Ye Bauk Kyar Taung Pyo Sin Thay Pyin #0 !< #0 C! Ah Shey Kha Maung Seik Sin Shey Myo Kha Mg Seick (Nord) !< Mi Kyaung Chaung Ah Htet Bo Ka Lay Baw Taw Lar !< !< Ah San Kyaw !< Hlaing Thi !< Nga Yant Chaung Nan Yar Kaing (M) Auk Bo Ka Lay Min Zi Li !< !< Kyee Hnoke Thee V# Thit Tone Nar Gwa Son BANGLADESH #0 Let Yar Chaung Kyaung Zar Hpyu XY Ta Man Thar Ah Shey (Ku Lar) Pan Zi Ta Man Thar (Thet) Ta Man Thar (Ku Lar) Middle !< C! XY Ta Man Thar Thea Kone Tan C! Ta Man Thar Ah Nauk Rakhine Nga/Myin Baw Kha Mway Ta Man Thar TaunXYg Ta Man Thar Zay Nar/ Tan Tta MXYan Thar (Bo Hmu Gyi Thet) Yae Nauk Ngar Thar (Daing Nat) C! Nga/Myin Baw Ku Lar Taungpyoletwea XY Yae Nauk Ngar Thar (!v® Hpaung Seik Taung Pyo Let Yar Mee Taik Ba Da Kar That Kaing Nyar (Thet) BUTHIDAUNG Tha Ra Zaing !< Ah Yaing Kwet Chay C! !<Laung Boke Long Boat Hpon Thi #0 Aung Zay Ya (Nyein Chan Yay) Thin Baw Hla (Ku Lar) That Chaung Pu Zun Chaung !< Gara Pyin Ye Aung Chaung Thin Baw Hla (Rakhine) (Thar -

China, India, and Myanmar: Playing Rohingya Roulette?

CHAPTER 4 China, India, and Myanmar: Playing Rohingya Roulette? Hossain Ahmed Taufiq INTRODUCTION It is no secret that both China and India compete for superpower standing in the Asian continent and beyond. Both consider South Asia and Southeast Asia as their power-play pivots. Myanmar, which lies between these two Asian giants, displays the same strategic importance for China and India, geopolitically and geoeconomically. Interestingly, however, both countries can be found on the same page when it comes to the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar’s Rakhine state. As the Myanmar army (the Tatmadaw) crackdown pushed more than 600,000 Rohingya refugees into Bangladesh, Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi’s government was vociferously denounced by the Western and Islamic countries.1 By contrast, China and India strongly sup- ported her beleaguered military-backed government, even as Bangladesh, a country both invest in heavily, particularly on a competitive basis, has sought each to soften Myanmar’s Rohingya crackdown and ease a medi- ated refugee solution. H. A. Taufiq (*) Global Studies & Governance Program, Independent University of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh e-mail: [email protected] © The Author(s) 2019 81 I. Hussain (ed.), South Asia in Global Power Rivalry, Global Political Transitions, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7240-7_4 82 H. A. TAUFIQ China’s and India’s support for Myanmar is nothing new. Since the Myanmar military seized power in September 1988, both the Asian pow- ers endeavoured to expand their influence in the reconfigured Myanmar to protect their national interests, including heavy investments in Myanmar, particularly in the Rakhine state. -

Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project

Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project A preliminary report from the Arakan Rivers Network (ARN) Preliminary Report on the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project November 2009 Copies - 500 Written & Published by Arakan Rivers Network (ARN) P.O Box - 135 Mae Sot Tak - 63110 Thailand Phone: + 66(0)55506618 Emails: [email protected] or [email protected] www.arakanrivers.net Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary …………………………………......................... 1 2. Technical Specifications ………………………………...................... 1 2.1. Development Overview…………………….............................. 1 2.2. Construction Stages…………………….................................... 2 3. Companies and Authorities Involved …………………....................... 3 4. Finance ………………………………………………......................... 3 4.1. Projected Costs........................................................................... 3 4.2. Who will pay? ........................................................................... 4 5. Who will use it? ………………………………………....................... 4 6. Concerns ………………………………………………...................... 4 6.1. Devastation of Local Livelihoods.............................................. 4 6.2. Human rights.............................................................................. 7 6.3. Environmental Damage............................................................. 10 7. India- Burma (Myanmar) Relations...................................................... 19 8. Our Aims and Recommendations to the media................................... -

Rakhine Operational Brief WFP Myanmar

Rakhine Operational Brief WFP Myanmar OVERVIEW Rakhine State is located in the western part of Myanmar, bordering with Chin State in the north, Magway, Bago and Ayeyarwaddy Regions in the east, Bay of Bengal to the west and Chittagong Division of Bangladesh to the northwest. It is one of the most remote and second poorest state in Myanmar, geographically separated from the rest of the country by mountains. The estimated population of Rakhine State is 3.2 million. Chronic poverty and high vulnerability to shocks are widespread throughout the State. Acute malnutrition remains a concern in Rakhine. The food security situation is particularly critical in Buthidaung and Maungdaw townships with 15.1 percent and 19 percent prevalence of global acute malnutrition (GAM) among children 6-59 months respectively. Meanwhile the prevalence of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) is 2 percent and 3.9 percent - above WHO critical emergency thresholds. The prevalence of GAM in Sittwe rural and urban IDP camps is 8.6 percent and 8.5 percent whereas the SAM prevalence is 1.3 percent and 0.6 percent. The existing malnutrition has been exacerbated by the 2015 nationwide floods as a Multi-sector Initial Rapid Assessment (MIRA) reported that 22 percent of assessed villages in Rakhine having nutrition problems with feeding children under 2. Moreover, WFP and FAO’s joint Crops and Food Security Assessment Mission in December 2015 predicted the likelihood of severe food shortage particularly in hardest hit areas of Rakhine. WFP is the main humanitarian organization providing uninterrupted food assistance in Rakhine. Its first PARTNERSHIPS operation in Myanmar commenced in 1978 in northern Rakhine, following the return of 200,000 refugees from Government Counterpart Bangladesh. -

Base Paper for the Committee on Development of Hill States

Base paper for the Committee to Study Development in Hill States arising from Management of Forest Lands Rita Pandey April 2012 National Institute of Public Finance and Policy New Delhi Contents 1. Introduction and Issues 1.1.1 General Issues 1.1.2 Persistent Poverty and Marginalization of Hill States 1.1.3 Lack of mountain specific development perspective and policies, and sound governance 1.1.4 Unclear Property Rights, Emerging Market for Ecosystem Services 1.1.5 Challenges in valuation of and lack of compensation for Ecosystem Goods and Services 1.2 Issues Related to Infrastructure in Hill States 1.2.1 North East Region (NER) States 1.2.2 Western Region Himalayan States 2. Status of Forests in Hill States 2.1 Estimates of Wasteland in India and Hill States 3. Forest Management Policies and Laws 3.1 Forest Management in Special Areas 3.2 Cross-Sectoral Linkages 3.3 Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest degradation (REDD) 3.4 Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority 4. The FCA, 1980 4.1 Basic Features 4.2 Organizational Set Up For Implementation of FCA 4.3 Functions of Regional Offices 4.4 Procedure for Grant of Approval under FCA, 1980 4.5 Earlier Recommendations/Observations/Proposals to speed up the approvals in this context 4.6 Approvals under FCA, 1980: Assessing the Performance 5. Views, Demands and Proposals of State Governments 5.1 Responses received from the hill states by this Committee 5.2 Based on the responses of the hill states to THFC 6. Strategy for Infrastructure Development References Tables Chart Annexure Base paper for the Committee to Study Development in Hill States arising from Management of Forest Lands 1. -

MYANMAR Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung Townships / Rakhine State

I Complex MYANMAR Æ Emergency Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung Townships / Rakhine State Imagery analysis: 31 August - 11 October 2017 | Published 17 November 2017 | Version 1.1 CE20130326MMR N 92°11'0"E 92°18'0"E 92°25'0"E 92°32'0"E 92°39'0"E 92°46'0"E 92°53'0"E N " " 0 ' 0 ' 5 5 Thimphu 2 2 ° ° 1 1 ¥¦¬ 2 Number of affected 2 C H I N A Township I N D I A settlements ¥¦¬Dhaka Buthidaung 34 Hano¥¦¬i Kyaung Toe Maungdaw 225 N Gu Mi Yar N " M YA N M A R " 0 ' 0 ' Naypyidaw 8 8 ¥¦¬ 1 Rathedaung 16 1 ° ° 1 Vientiane 1 2 Map location 2 ¥¦¬ Taing Bin Gar T H A I L A N D Baw Taw Lar Mi Kyaung Chaung Thit Tone Nar Gwa Son Bangkok ¥¦¬ Ta Man Thar Ah Nauk Rakhine Phnom Penh Ta Man Thar Thea Kone Tan Yae Nauk Ngar Thar N N " ¥¦¬ " 0 ' 0 Tat Chaung ' 1 Ye Aung Chaung 1 1 1 ° ° 1 Than Hpa Yar 1 2 Pa Da Kar Taung Mu Hti 2 Kyaw U Let Hpweit Kya Done Ku Lar Kyun Taung Destroyed areas in Buthidaung, Kyet Kyein See inset for close-up view of Maungdaw, and Rathedaung Kyun Pauk Sin Oe San Kar Pin Yin destroyed structures Kyun Pauk Pyu Su Goke Pi Townships of Rakhine State in Hpaw Ti Kaung N Thaung Khu Lar N " " 0 ' 0 ' 4 Gyit Chaung 4 Myanmar ° Sa Bai Kone ° 1 1 2 Lin Bar Gone Nar 2 This map illustrates areas of satellite- Pyaung Pyit detected destroyed or otherwise damaged Yin Ma Kyaung Taung Tha Dut Taung settlements in Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Yin Ma Zay Kone Taung Rathedaung Townships in the Maungdaw and Sittwe Districts of Rakhine State in Myanmar. -

Myanmar: the Key Link Between

ADBI Working Paper Series Myanmar: The Key Link between South Asia and Southeast Asia Hector Florento and Maria Isabela Corpuz No. 506 December 2014 Asian Development Bank Institute Hector Florento and Maria Isabela Corpuz are consultants at the Office of Regional Economic Integration, Asian Development Bank. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. In this paper, “$” refers to US dollars. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. ADBI encourages readers to post their comments on the main page for each working paper (given in the citation below). Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Florento, H., and M. I. Corpuz. 2014. Myanmar: The Key Link between South Asia and Southeast Asia. ADBI Working Paper 506. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: http://www.adbi.org/working- paper/2014/12/12/6517.myanmar.key.link.south.southeast.asia/ Please contact the authors for information about this paper. -

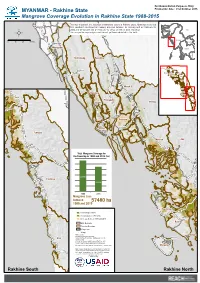

Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015

For Humanitarian Purposes Only MYANMAR - Rakhine State Production date : 21st October 2015 Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015 This map illustrates the evolution of mangrove extent in Rakhine State, Myanmar as derived Bhutan from Landsat-5 multispectral imagery acquired between 13 January and 23 February for Nepal Mindat 1988 and 30 January and 24 February for 2015 at 30m of pixel resolution. India China Town Bangladesh Bangladesh This is a preliminary analysis and has not yet been validated in the field. Paletwa Town Viet Nam Myanmar 0 10 20 30 Kms Laos Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Town Town Maungdaw Thailand Buthidaung Kyauktaw Cambodia Taungpyoletwea Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Town Buthidaung Kyauktaw Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Mrauk-U Town Maungdaw Rathedaung Mrauk-U Ponnagyun Town Minbya Rathedaung Ponnagyun Pauktaw Minbya Sittwe Pauktaw Myebon Sittwe Myebon Ann Ann Mrauk-U Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Kyaukpyu Ramree Ramree Toungup Rathedaung Mrauk-U Munaung Munaung Toungup Town Ann Thandwe Ponnagyun Thandwe Rathedaung Minbya Kyeintali Mindon Ma-Ei Town Town Town Gwa Gwa Ramree Minbya Town Ponnagyun Town Pauktaw Sittwe Pauktaw Town Sittwe Toungup Town Myebon Town Myebon Ann Toungup Town Total Mangrove Coverage for the Township in 1988 and 2015 (ha) Ann Town Thandwe Town 280986 Thandwe 223506 Kyaukpyu 1988 2015 Town Mangrove Loss between 57480 ha 1988 and 2015 Kyaukpyu New Mangrove area Kyeintali Town Remaining area 1988-2015 Ramree Decrease between 1988 and 2015 Town Ramree State Boundary Township Boundary Village-Tract Village Data sources: Toungup Landcover Analysis: UNOSAT Administrative Boundaries, Settlements: OCHA Munaung Gwa Town Roads: OSM Coordinate System: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 46N Contact: [email protected] File: REACH_MMR_Map_Rakhine_HVA_Mangrove_21OCT2015_A1 Munaung Note: Data, designations and boundaries contained Gwa Town on this map are not warranted to be error-free and do not imply acceptance by the REACH partners, associated, donors mentioned on this map. -

139416 Rakhine State

Rakhine State (Myanmar) as of 22 May 2013 Total Estimated IDP Population 139,416 Total Number of Households 22,773 Rakhine Situation Overview Inter-community conflict in Rakhine State, which erupted in early June 2012 and resurfaced in October 2012, has resulted in displacement and loss of lives and livelihoods. As of beginning of April 2013, the number of people displaced in Rakhine State has surpassed 139,000, of whom about 75,000 displaced since June 2012 and the remaining following Kyauktaw October. Many others continue living in tents close to their places of origin while their houses are being rebuilt, or with Maungdaw 6418 host families. The IDP population is currently hosted in 76 camps and camp-like settings. The Shelter/NFI/CCCM Cluster 3569 was activated in December 2012 in Yangon. Only more recently (middle March 2013) did the CCCM Cluster become Mrauk-U operational in Rakhine State. Therefore the sectoral response is still at a very early stage at field level. Rathedaung 4135 4008 Minbya Number of IDP sites by township IDP population by township 5152 as of 22 May 2013 as of 22 May 2013 Sittwe Pauktaw Minbya 8 Minbya 5,152 19976 Meybon Mrauk-U 4 Mrauk-U 4,135 89880 4169 Meybon 2 Meybon 4,169 Pauktaw 6 Pauktaw 19,976 Kyauktaw 11 Kyauktaw 6,418 Rathedaung 4 Rathedaung 4,008 Kyauk Phyu 2 Kyauk Phyu 1,849 Kyauk Phyu Ramree 2 Rakhine Ramree 260 1849 Sittwe 23 Sittwe 89,880 Maungdaw 14 Maungdaw 3,569 Type of accomodation at IDP sites Ramree Number of IDP sites IDP population by type of 260 'Planned / Managed Camp' purpose-built sites by type of accommodation accommodation where services and infrastructure is provided 139,416IDPs including water supply, food distribution, non- food item, education, and health care, usually targeted by humanitarian partners exclusively for the population of the site. -

Languages in the Rohingya Response

Languages in the Rohingya response This overview relates to a Translators without Borders (TWB) study of the role of language in humanitarian service access and community relations in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh and Sittwe, Myanmar. Language use and word choice has implications for culture, identity and politics in the Myanmar context. Six languages play a role in the Rohingya response in Myanmar and Bangladesh. Each brings its own challenges for translation, interpretation, and general communication. These languages are Bangla, Chittagonian, Myanmar, Rakhine, Rohingya, and English. Bangla Bangla’s near-sacred status in Bangladeshi society derives from the language’s tie to the birth of the nation. Bangladesh is perhaps the only country in the world which was founded on the back of a language movement. Bangladeshi gained independence from Pakistan in 1971, among other things claiming their right to use Bangla and not Urdu. Bangladeshis gave their lives for the cause of preserving their linguistic heritage and the people retain a patriotic attachment to the language. The trauma of the Liberation War is still fresh in the collective memory. Pride in Bangla as the language of national unity is unique in South Asia - a region known for its cultural, religious, and linguistic diversity. Despite the elevated status of Bangla, the country is home to over 40 languages and dialects. This diversity is not obvious because Bangladeshis themselves do not see it as particularly important. People across the country have a local language or dialect apart from Bangla that is spoken at home and with neighbors and friends. But Bangla is the language of collective, national identity - it is the language of government, commerce, literature, music and film.