Enter the Void

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enter the Void: Raumaufsichten Und Wegweisende Perspektiven in Subkulturen“

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Gaspar Noés Enter the Void: Raumaufsichten und wegweisende Perspektiven in Subkulturen“ Verfasser Amelio August Nicotera angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 317 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Theater-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft Betreuerin: ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Brigitte Marschall i „Jed e K u n st gelan gte dab ei zu dem dialek tisch en U m sch lagsp u n k t, w o die M ittel den Zweck und die Formen den Inhalt zu bestimm en begonnen haben. Jed e gelan gte au ch bis zu r letzten logisch en K on seq u en z: zur Form , die sich selber In h alt ist. Also zum Nichts.“1 1 B a lá z s , B é la , Der Geist des Films, F r a n k fu r t a m M a in : S u h r k a m p 2 0 0 1 , S .7 0 ii iii Danksagung Mein Dank gilt Barbara Hum m el Gudrun und Ruben Nicotera iv v In h altsverzeich n is 1. Einleitung.......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Vorw ort................................................................................................................. 1 1.2. Forschungsfragen und Aufbau der Arbeit......................................................... 3 2. Perspektiven...................................................................................................................... 5 2.1. Gaspar Noé: Einflüsse, W erke und zeitliche Einbettung.................................5 2.2. Der Rezipient......................................................................................................14 -

1997 Sundance Film Festival Awards Jurors

1997 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL The 1997 Sundance Film Festival continued to attract crowds, international attention and an appreciative group of alumni fi lmmakers. Many of the Premiere fi lmmakers were returning directors (Errol Morris, Tom DiCillo, Victor Nunez, Gregg Araki, Kevin Smith), whose earlier, sometimes unknown, work had received a warm reception at Sundance. The Piper-Heidsieck tribute to independent vision went to actor/director Tim Robbins, and a major retrospective of the works of German New-Wave giant Rainer Werner Fassbinder was staged, with many of his original actors fl own in for forums. It was a fi tting tribute to both Fassbinder and the Festival and the ways that American independent cinema was indeed becoming international. AWARDS GRAND JURY PRIZE JURY PRIZE IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Documentary—GIRLS LIKE US, directed by Jane C. Wagner and LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY (O SERTÃO DAS MEMÓRIAS), directed by José Araújo Tina DiFeliciantonio SPECIAL JURY AWARD IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Dramatic—SUNDAY, directed by Jonathan Nossiter DEEP CRIMSON, directed by Arturo Ripstein AUDIENCE AWARD JURY PRIZE IN SHORT FILMMAKING Documentary—Paul Monette: THE BRINK OF SUMMER’S END, directed by MAN ABOUT TOWN, directed by Kris Isacsson Monte Bramer Dramatic—HURRICANE, directed by Morgan J. Freeman; and LOVE JONES, HONORABLE MENTIONS IN SHORT FILMMAKING directed by Theodore Witcher (shared) BIRDHOUSE, directed by Richard C. Zimmerman; and SYPHON-GUN, directed by KC Amos FILMMAKERS TROPHY Documentary—LICENSED TO KILL, directed by Arthur Dong Dramatic—IN THE COMPANY OF MEN, directed by Neil LaBute DIRECTING AWARD Documentary—ARTHUR DONG, director of Licensed To Kill Dramatic—MORGAN J. -

Voiding Cinema: Subjectivity Beside Itself, Or Unbecoming Cinema in Enter the Void - William Brown, University of Roehampton ([email protected])

Film-Philosophy 19 (2015) Voiding Cinema: Subjectivity Beside Itself, or Unbecoming Cinema in Enter the Void - William Brown, University of Roehampton ([email protected]) David H. Fleming, University of Nottingham Ningbo China ([email protected]) The whole thing is about getting into holes. Putting the camera into any hole. (Gasper Noé, quoted in Adams 2010) In this essay, we provide a close textual analysis of Enter the Void (Gaspar Noé, France/Germany/Italy, 2009). Using concepts from the work of Gilles Deleuze, we argue that the film’s form reflects the narrative’s preoccupation with the liminal space between life and death, between subject and object, between inside and outside –which we characterise here as the void. Indeed, Enter the Void not only tells the story of a man suspended between life and death, but formally it also tries to depict this liminal state, to show us the void itself – or to bring what normally exceeds vision into view (to turn excess into ‘incess’). Through its creative synthesis of form and content, the film attempts to force viewers to think or conceptualise the notoriously complex notion of void. Looking first at how film theory can help us to understand the film, we then investigate ways in which Enter the Void can enrich film theory and our understanding of cinema more generally, in particular our understanding of what film can do in the digital era. Incorporating ideas from neuroscience, from physics, and from somewhat esoteric research into hallucinogens, we propose that Enter the Void suggests a cinema that emphasises the related nature of all things, a related nature that we can see by being ‘beside oneself’, a process that cinema itself helps us to achieve. -

Deviant Phenomenal Models in Gaspar Noé's Enter the Void

The Cognitive Import of Contemporary Cinema: Deviant Phenomenal Models in Gaspar Noé’s Enter the Void Jon Lindblom In his brief but illuminating essay ‘Genre is Obsolete’, Ray Brassier criticizes the commitment of much contemporary critical theory to the transformative potency of so-called ‘lived’, or ‘aesthetic’, experience. (Brassier 2007) For Brassier, the latter is merely a cultural residue of early bourgeoisie modernity whose supposedly critical injunction has been vitiated by recent advancements in modern neuroscience which harbors a decisive cognitive and socio-cultural import: the objectification of lived experience. Indeed, rather than being a mere abstract exercise played out exclusively at the level of theoretical science, the techno-scientific mapping of the neural correlates underlying global information-processing (qua lived experience) will surely have both practical and concrete consequences in the domain of subjective and intersubjective experience; most immediately, perhaps, through their inevitable commercialization (in the form of cosmetic neuropharmacology, neuromarketing, cognitive enhancers, etc.) which undoubtedly will find their place within the capitalist economy. Yet rather than recoil in horror over these developments, such as by affirming the so-called ‘unobjectifiable’ condition of human existence (whether characterized as ‘experience’ or anything else), what is necessary for any form of theory that intends to deem itself critical in the current context is a major update of its cognitive commitments, which only will be achieved through a thorough reconsideration of the intricate relationship between the social, the cultural, the personal, and the neurobiological. 1 The current essay aims to present the rudiments for such a cognitive reconsideration viewed through a cultural lens, through the medium of film – or, more specifically, through Gaspar Noé’s psychedelic melodrama Enter the Void (2010). -

Pristup Cjelovitom Tekstu Rada

Plakat za film Ljubav, 2015. A poster for the film Želim samo da Love, 2015 me (ne) volite (wbd) napisao written by I Just Want You Željko Luketić (Not) to Love Me portret portrait Rick Loomis, fotografije photography by Arhiva / Archive Canal+ (cp); Arhiva / Archive Les Cinémas de la Zone (cz); Los Angeles Times Arhiva / Archive Wild Bunch Distribution (wbd) autor ¶ In the 1930s, film audiences were frightened by Dracula’s and author Frankenstein’s, in the 1940s, Abbott and Costello used the pair to keep their audiences in stitches, whereas in the 1950s, there were giant tarantulas and the fear of nuclear war. Zombies were born a decade later, but the horror genre flourished anew in the freedom-loving 1970s. It is in this sequence that the Canadian documentary Why Horror? (2014), through a story about the social acceptability of a movie fan, tries to speak about what is at the same time the universal question of that part of film history: why we are afraid and why we like to be frightened even more. The aforementioned film offers a warm American story about how confronting our primordial and unconscious demons is precisely the way to counter those fears bravely and directly. What it lacks, however, is something that, in the art of filmmaking, has been maturing for a long time and in detail, something for which the origin of the horror genre is just the inspiration, and which manifests itself even more potently in Gaspar Noé 198 oris, broj 96, godina 2015. oris, number 96, year 2015 gaspar noé, Film gaspar noé, Film 199 Kadrovi iz filma Ulaz u prazninu, 2009. -

“You'll Get Your Big Trip”: Acousmatic Music, the Voice, and the Mirror

www.thecine-files.com FEATURED SCHOLARSHIP “You’ll Get Your Big Trip”: Acousmatic Music, The Voice, and the Mirror Stage in Enter the Void Mark Balderston “Am I hearing voices in the voice? But is it not the truth of the voice to be hallucinated? Is not the entire space of the voice an infinite space?” – Roland Barthes1 Gaspar Noé’s Enter the Void (2009) recounts the psychedelic experienc- es and afterlife of its protagonist Oscar from an unconventional first-person 2 perspective. Over the course of the film, the audience will observe a DMT (dimethyltryptamine) trip in Oscar’s mind, experience his death and the tragic aftermath for his loved ones, and finally observe his re-birth—seeing and hearing through Oscar’s perceptions, and experiencing his hallucinations, dreams, and 3 memories. Even after his death, the audience assumes the viewpoint of his dis- embodied ghost. In order to convey its disjointed and subjective narrative, Enter the Void eschews continuity editing techniques such as shot/reverse-shot and match-on-action in favor of hidden edits, jump cuts, and extended visual effects 4 transitions. Though critical response to the film was largely divided, critics con- sistently lauded the film’s visual style, remarking upon its effective use of mise- en-scène and cinematography to accomplish its unique sensory perspective. Often overlooked, however, is the role of sound in constructing the spatio-tem- poral displacements that help establish Enter the Void’s hallucinatory universe. The film’s use of sound is as unorthodox as its visual style, using an abstract electronic score that blurs the distinctions between score and sound effects, and a highly subjective treatment of the voice, rather than “realistic” Hollywood-style conventions. -

Pleasurev.1 Final

Pornography & The Law Namita Malhotra Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 3 The Knowing yet Blindfolded ‘Gaze’ of Law upon the Profane ........................................ 6 Pornography the Trials and Tribulations of the Indian Courts ......................................... 19 Family Jewels and Public Secrets ..................................................................................... 33 Film, Video and Body ....................................................................................................... 47 Amateur Video Pornography ............................................................................................ 60 Downloading the State —Porn, Tech, Law ...................................................................... 76 The Technology Beast ...................................................................................................... 88 Vignettes for the ‘Next’ .................................................................................................. 102 Page | 2 Introduction “If you really want to be amazed at the total sightlessness of your blind spot, do a test outside at night when there is a full moon. Cover your left eye, looking at the full moon with your right eye. Gradually move your right eye to the left (and maybe slightly up or down). Before long, all you will be able to see is the large halo around the full moon; the entire moon itself will seem to have disappeared.” -

329 Sterbak F

art press 333 interview Larry Clark l’œil du cyclone Interview par Raphaël Cuir Il y a presque un an, était présenté au Festival de Cannes, Destricted, programme de sept courts métrages signés par Marina Abramovic, Matthew Barney, Gaspar Noé, Richard Prince, Marco Brambilla, Sam Taylor- Wood et Larry Clark. Il s’agissait de répondre à l’incitation des producteurs, Mel Agace et Neville Wakefield : aborder la sexualité «de facon explicite», autrement dit, brouiller la frontière entre art et pornographie. Ce programme sort maintenant en salles en France (le 25 avril) et bientôt en DVD (en octobre). Bonne occasion pour réaliser notre vieux rêve de rencontrer Larry Clark, il faut dire, le plus explicite de tous (1). Les images de la série Tulsa (1963-1971) ne sont peut-être plus aussi subversives qu’il y a une quarantaine d’années. Pour autant, elles n’ont rien perdu de leur intensité. Cette violence, Larry Clark dit qu’il faut en payer le prix, c’est-à-dire le prix émotionnel. C’était autrefois le retour du refoulé, l’autre face du rêve américain dont certains, certaines, ne sont pas revenus. C’est encore, aujourd’hui, ouvrir «en entier la nature humaine à la conscience de soi !» (G. Bataille). «On ne peut pas savoir ce que peut le corps» (B. Spinoza), il faut chercher, et nous n’avons pas fini d’être étonnés (F. Nietzsche : «L’étonnant c’est le corps.»). L’adolescence est un des moments privilégiés de cette quête avec la découverte des nouvelles possibilités qu’offre la maturité corporelle. -

Amazonian Visions: Animating Ghosts by Gustavo Cerquera Benjumea a Thesis Supporting Paper Presented to the Ontario College of A

Amazonian Visions: Animating Ghosts by Gustavo Cerquera Benjumea A thesis supporting paper presented to the Ontario College of Art & Design University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Interdisciplinary Master’s in Art, Media and Design Program 100 McCaul St. Toronto, Ontario, M5T 1W1, Canada, May 9th, 2013 © Gustavo Cerquera Benjumea 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize the Ontario College of Art & Design to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. I further authorize the Ontario College of Art & Design to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Signature __________________________________________________ ii Amazonian Visions: Animating Ghosts Master of Fine Art, 2013 Gustavo Cerquera Benjumea Interdisciplinary Master’s in Art, Media and Design OCAD University Abstract Amazonian Visions is a practice-based research project that finds associations between the concepts of expanded cinema and animation, and the myriad worlds of the Amazonian psychedelic brew, ayahuasca. I argue that expanded animation is a medium not unlike cultural practices of expanded vision and psychedelic experiences inspired by ayahuasca. By juxtaposing these two concepts, tracing their genealogies, and examining unexpected links between the two, I propose that both are techniques that allow the fantastical to enter the ordinary. -

7 Days / 7 Directors ©Full House – Morena Films

FULL HOUSE AND MORENA FILMS IN COLLABORATION WITH HAVANA CLUB INTERNATIONAL SA PRESENT A FILM BY BENICIO DEL TORO PABLO TRAPERO JULIO MEDEM ELIA SULEIMAN GASPAR NOÉ JUAN CARLOS TABÍO LAURENT CANTET 7 DAYS / 7 DIRECTORS ©FULL HOUSE – MORENA FILMS. CREDITS NOT CONTRACTUAL CONTRACTUAL ©FULL HOUSE – MORENA FILMS. CREDITS NOT Full House & Morena Films In collaboration with Havana Club International S.A present A fi lm by BENICIO DEL TORO PABLO TRAPERO JULIO MEDEM ELIA SULEIMAN GASPAR NOÉ JUAN CARLOS TABÍO LAURENT CANTET Running time: 2h09 – Visa 128.944 – 1.85 – Dolby Digital Download press kit and photos from www.wildbunch.biz/fi lms/7_days_in_havana INTERNATIONAL SALES INTERNATIONAL PRESS: RENDEZ VOUS 4 La Croisette – 1st fl oor (In front of the Palais) Viviana ANDRIANI: [email protected] Phone: +33 (0) 4 93 30 17 46 +33 6 80 16 81 39 Carole BARATON: [email protected] Aurélie DARD: [email protected] Gary FARKAS: [email protected] +33 6 77 04 52 20 Vincent MARAVAL: [email protected] Gaël NOUAILLE: [email protected] Silvia SIMONUTTI: [email protected] 7 DAYS IN HAVANA is a snapshot of Havana in 2011: a contemporary portrait of this eclectic city, vital and forward-looking, told through a single feature- length movie made up of 7 chapters, directed by Benicio del Toro, Pablo Trapero, Julio Medem, Elia Suleiman, Gaspar Noé, Juan Carlos Tabío and Laurent Cantet. Each director, through his own sensibility, origins, and cinematographic style, has caught the energy and the vitality that makes this city unique. Some have chosen to meet cuban reality in tune with its everyday life, through the eyes of the foreigner far from his familiar points of reference. -

84B03f4e2a7eef9b2fe0fbb7715b

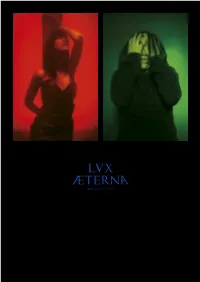

LUX ÆTERNA GASPAR NOE CANNES FILM FESTIVAL 2019 OFFICIAL SELECTION - MIDNIGHT SCREENING PRESENTED BY SAINT LAURENT SELF 04 Cannes Film Festival selected “Lux Æterna”, a 50 minute “film within the film” directed by Gaspar Noé, in Official Selection, as part of the midnight session projected on the 18th of May at Théâtre Lumière. A vibrant essay on respect for beliefs, the actor’s craft and the art of filmmaking that stages Béatrice Dalle, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Abbey Lee, Anatole Devoucoux du Buysson, Clara 3000, Claude-Emmanuelle Gajan-Maull, Felix Maritaud, Fred Cambier,Karl Glusman, Lola Pillu Perier, Loup “Vuk” Brankovic, Luka Isaac, Maxime Ruiz, Mica Arganaraz, Paul Hameline, Philippe Mensah, Stefania Cristian, Tom Kan, Victor Sekularac and Yannick Bono. “Last February Anthony proposed to support me if I had any idea for a short film. Two weeks later, in five days, with Béatrice and Charlotte we improvised this modest essay about beliefs and the art of filmmaking. Now the 51 minute baby is ready to scream… Thank God, cinema is light flashing 24 frames-per-second”. Gaspar “Lux Æterna” is the fourth incarnation of the international art project, SELF - curated by Saint Laurent’s creative director, Anthony Vaccarello. This project is an artistic commentary on society while emphasizing the complexity of various individuals through the eyes of artists who evoke the Saint Laurent attitude of confidence, individuality and self-expression. To this end, Vaccarello commissioned Gaspar Noé, who is instinctively aligned with the spirit of the brand, to direct SELF04 with Béatrice Dalle and Charlotte Gainsbourg. “Gaspard is one of the most talented artist nowadays. -

THE DIGITAL IMAGE and REALITY Affect, Metaphysics and Post-Cinema Daniel Strutt

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION THE DIGITAL IMAGE AND REALITY Affect, Metaphysics and Post-Cinema daniel strutt FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS The Digital Image and Reality FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS The Digital Image and Reality Affect, Metaphysics, and Post-Cinema Dan Strutt Amsterdam University Press FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Cover illustration: Studio Aszyk, London. Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 713 5 e-isbn 978 90 4853 865 2 doi 10.5117/9789462987135 nur 670 © D. Strutt / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2019 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Contents Acknowledgements 7 1. Cinema’s Foundational Frissons 9 The Arrival of the Digital Image at the Station 9 A Futurist Cinema of Attractions 13 What is Post about Post-Cinema? 21 But is it Art? 26 From Cine-thinking to Digi-thinking 30 Technology and Reality 34 2. The Affective Synthesis of Reality by Digital Images 41 A Great Evolution 42 A Question of Cause and Responsibility 44 Cinema and Affection 48 Passive Synthesis and the Spiritual Automaton 51 Do We Need a New ‘Digital’ Image Type – A ‘Cinema 3’? 58 The Digital Revealing of Reality 60 Interstellar’s Ontological Revealing 64 The Digital Pharmakon 67 Plasticity and Politics 72 3.