Deviant Phenomenal Models in Gaspar Noé's Enter the Void

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enter the Void: Raumaufsichten Und Wegweisende Perspektiven in Subkulturen“

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Gaspar Noés Enter the Void: Raumaufsichten und wegweisende Perspektiven in Subkulturen“ Verfasser Amelio August Nicotera angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 317 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Theater-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft Betreuerin: ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Brigitte Marschall i „Jed e K u n st gelan gte dab ei zu dem dialek tisch en U m sch lagsp u n k t, w o die M ittel den Zweck und die Formen den Inhalt zu bestimm en begonnen haben. Jed e gelan gte au ch bis zu r letzten logisch en K on seq u en z: zur Form , die sich selber In h alt ist. Also zum Nichts.“1 1 B a lá z s , B é la , Der Geist des Films, F r a n k fu r t a m M a in : S u h r k a m p 2 0 0 1 , S .7 0 ii iii Danksagung Mein Dank gilt Barbara Hum m el Gudrun und Ruben Nicotera iv v In h altsverzeich n is 1. Einleitung.......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Vorw ort................................................................................................................. 1 1.2. Forschungsfragen und Aufbau der Arbeit......................................................... 3 2. Perspektiven...................................................................................................................... 5 2.1. Gaspar Noé: Einflüsse, W erke und zeitliche Einbettung.................................5 2.2. Der Rezipient......................................................................................................14 -

Voiding Cinema: Subjectivity Beside Itself, Or Unbecoming Cinema in Enter the Void - William Brown, University of Roehampton ([email protected])

Film-Philosophy 19 (2015) Voiding Cinema: Subjectivity Beside Itself, or Unbecoming Cinema in Enter the Void - William Brown, University of Roehampton ([email protected]) David H. Fleming, University of Nottingham Ningbo China ([email protected]) The whole thing is about getting into holes. Putting the camera into any hole. (Gasper Noé, quoted in Adams 2010) In this essay, we provide a close textual analysis of Enter the Void (Gaspar Noé, France/Germany/Italy, 2009). Using concepts from the work of Gilles Deleuze, we argue that the film’s form reflects the narrative’s preoccupation with the liminal space between life and death, between subject and object, between inside and outside –which we characterise here as the void. Indeed, Enter the Void not only tells the story of a man suspended between life and death, but formally it also tries to depict this liminal state, to show us the void itself – or to bring what normally exceeds vision into view (to turn excess into ‘incess’). Through its creative synthesis of form and content, the film attempts to force viewers to think or conceptualise the notoriously complex notion of void. Looking first at how film theory can help us to understand the film, we then investigate ways in which Enter the Void can enrich film theory and our understanding of cinema more generally, in particular our understanding of what film can do in the digital era. Incorporating ideas from neuroscience, from physics, and from somewhat esoteric research into hallucinogens, we propose that Enter the Void suggests a cinema that emphasises the related nature of all things, a related nature that we can see by being ‘beside oneself’, a process that cinema itself helps us to achieve. -

Pristup Cjelovitom Tekstu Rada

Plakat za film Ljubav, 2015. A poster for the film Želim samo da Love, 2015 me (ne) volite (wbd) napisao written by I Just Want You Željko Luketić (Not) to Love Me portret portrait Rick Loomis, fotografije photography by Arhiva / Archive Canal+ (cp); Arhiva / Archive Les Cinémas de la Zone (cz); Los Angeles Times Arhiva / Archive Wild Bunch Distribution (wbd) autor ¶ In the 1930s, film audiences were frightened by Dracula’s and author Frankenstein’s, in the 1940s, Abbott and Costello used the pair to keep their audiences in stitches, whereas in the 1950s, there were giant tarantulas and the fear of nuclear war. Zombies were born a decade later, but the horror genre flourished anew in the freedom-loving 1970s. It is in this sequence that the Canadian documentary Why Horror? (2014), through a story about the social acceptability of a movie fan, tries to speak about what is at the same time the universal question of that part of film history: why we are afraid and why we like to be frightened even more. The aforementioned film offers a warm American story about how confronting our primordial and unconscious demons is precisely the way to counter those fears bravely and directly. What it lacks, however, is something that, in the art of filmmaking, has been maturing for a long time and in detail, something for which the origin of the horror genre is just the inspiration, and which manifests itself even more potently in Gaspar Noé 198 oris, broj 96, godina 2015. oris, number 96, year 2015 gaspar noé, Film gaspar noé, Film 199 Kadrovi iz filma Ulaz u prazninu, 2009. -

“You'll Get Your Big Trip”: Acousmatic Music, the Voice, and the Mirror

www.thecine-files.com FEATURED SCHOLARSHIP “You’ll Get Your Big Trip”: Acousmatic Music, The Voice, and the Mirror Stage in Enter the Void Mark Balderston “Am I hearing voices in the voice? But is it not the truth of the voice to be hallucinated? Is not the entire space of the voice an infinite space?” – Roland Barthes1 Gaspar Noé’s Enter the Void (2009) recounts the psychedelic experienc- es and afterlife of its protagonist Oscar from an unconventional first-person 2 perspective. Over the course of the film, the audience will observe a DMT (dimethyltryptamine) trip in Oscar’s mind, experience his death and the tragic aftermath for his loved ones, and finally observe his re-birth—seeing and hearing through Oscar’s perceptions, and experiencing his hallucinations, dreams, and 3 memories. Even after his death, the audience assumes the viewpoint of his dis- embodied ghost. In order to convey its disjointed and subjective narrative, Enter the Void eschews continuity editing techniques such as shot/reverse-shot and match-on-action in favor of hidden edits, jump cuts, and extended visual effects 4 transitions. Though critical response to the film was largely divided, critics con- sistently lauded the film’s visual style, remarking upon its effective use of mise- en-scène and cinematography to accomplish its unique sensory perspective. Often overlooked, however, is the role of sound in constructing the spatio-tem- poral displacements that help establish Enter the Void’s hallucinatory universe. The film’s use of sound is as unorthodox as its visual style, using an abstract electronic score that blurs the distinctions between score and sound effects, and a highly subjective treatment of the voice, rather than “realistic” Hollywood-style conventions. -

Amazonian Visions: Animating Ghosts by Gustavo Cerquera Benjumea a Thesis Supporting Paper Presented to the Ontario College of A

Amazonian Visions: Animating Ghosts by Gustavo Cerquera Benjumea A thesis supporting paper presented to the Ontario College of Art & Design University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Interdisciplinary Master’s in Art, Media and Design Program 100 McCaul St. Toronto, Ontario, M5T 1W1, Canada, May 9th, 2013 © Gustavo Cerquera Benjumea 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize the Ontario College of Art & Design to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. I further authorize the Ontario College of Art & Design to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Signature __________________________________________________ ii Amazonian Visions: Animating Ghosts Master of Fine Art, 2013 Gustavo Cerquera Benjumea Interdisciplinary Master’s in Art, Media and Design OCAD University Abstract Amazonian Visions is a practice-based research project that finds associations between the concepts of expanded cinema and animation, and the myriad worlds of the Amazonian psychedelic brew, ayahuasca. I argue that expanded animation is a medium not unlike cultural practices of expanded vision and psychedelic experiences inspired by ayahuasca. By juxtaposing these two concepts, tracing their genealogies, and examining unexpected links between the two, I propose that both are techniques that allow the fantastical to enter the ordinary. -

7 Days / 7 Directors ©Full House – Morena Films

FULL HOUSE AND MORENA FILMS IN COLLABORATION WITH HAVANA CLUB INTERNATIONAL SA PRESENT A FILM BY BENICIO DEL TORO PABLO TRAPERO JULIO MEDEM ELIA SULEIMAN GASPAR NOÉ JUAN CARLOS TABÍO LAURENT CANTET 7 DAYS / 7 DIRECTORS ©FULL HOUSE – MORENA FILMS. CREDITS NOT CONTRACTUAL CONTRACTUAL ©FULL HOUSE – MORENA FILMS. CREDITS NOT Full House & Morena Films In collaboration with Havana Club International S.A present A fi lm by BENICIO DEL TORO PABLO TRAPERO JULIO MEDEM ELIA SULEIMAN GASPAR NOÉ JUAN CARLOS TABÍO LAURENT CANTET Running time: 2h09 – Visa 128.944 – 1.85 – Dolby Digital Download press kit and photos from www.wildbunch.biz/fi lms/7_days_in_havana INTERNATIONAL SALES INTERNATIONAL PRESS: RENDEZ VOUS 4 La Croisette – 1st fl oor (In front of the Palais) Viviana ANDRIANI: [email protected] Phone: +33 (0) 4 93 30 17 46 +33 6 80 16 81 39 Carole BARATON: [email protected] Aurélie DARD: [email protected] Gary FARKAS: [email protected] +33 6 77 04 52 20 Vincent MARAVAL: [email protected] Gaël NOUAILLE: [email protected] Silvia SIMONUTTI: [email protected] 7 DAYS IN HAVANA is a snapshot of Havana in 2011: a contemporary portrait of this eclectic city, vital and forward-looking, told through a single feature- length movie made up of 7 chapters, directed by Benicio del Toro, Pablo Trapero, Julio Medem, Elia Suleiman, Gaspar Noé, Juan Carlos Tabío and Laurent Cantet. Each director, through his own sensibility, origins, and cinematographic style, has caught the energy and the vitality that makes this city unique. Some have chosen to meet cuban reality in tune with its everyday life, through the eyes of the foreigner far from his familiar points of reference. -

84B03f4e2a7eef9b2fe0fbb7715b

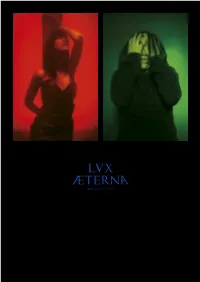

LUX ÆTERNA GASPAR NOE CANNES FILM FESTIVAL 2019 OFFICIAL SELECTION - MIDNIGHT SCREENING PRESENTED BY SAINT LAURENT SELF 04 Cannes Film Festival selected “Lux Æterna”, a 50 minute “film within the film” directed by Gaspar Noé, in Official Selection, as part of the midnight session projected on the 18th of May at Théâtre Lumière. A vibrant essay on respect for beliefs, the actor’s craft and the art of filmmaking that stages Béatrice Dalle, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Abbey Lee, Anatole Devoucoux du Buysson, Clara 3000, Claude-Emmanuelle Gajan-Maull, Felix Maritaud, Fred Cambier,Karl Glusman, Lola Pillu Perier, Loup “Vuk” Brankovic, Luka Isaac, Maxime Ruiz, Mica Arganaraz, Paul Hameline, Philippe Mensah, Stefania Cristian, Tom Kan, Victor Sekularac and Yannick Bono. “Last February Anthony proposed to support me if I had any idea for a short film. Two weeks later, in five days, with Béatrice and Charlotte we improvised this modest essay about beliefs and the art of filmmaking. Now the 51 minute baby is ready to scream… Thank God, cinema is light flashing 24 frames-per-second”. Gaspar “Lux Æterna” is the fourth incarnation of the international art project, SELF - curated by Saint Laurent’s creative director, Anthony Vaccarello. This project is an artistic commentary on society while emphasizing the complexity of various individuals through the eyes of artists who evoke the Saint Laurent attitude of confidence, individuality and self-expression. To this end, Vaccarello commissioned Gaspar Noé, who is instinctively aligned with the spirit of the brand, to direct SELF04 with Béatrice Dalle and Charlotte Gainsbourg. “Gaspard is one of the most talented artist nowadays. -

THE DIGITAL IMAGE and REALITY Affect, Metaphysics and Post-Cinema Daniel Strutt

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION THE DIGITAL IMAGE AND REALITY Affect, Metaphysics and Post-Cinema daniel strutt FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS The Digital Image and Reality FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS The Digital Image and Reality Affect, Metaphysics, and Post-Cinema Dan Strutt Amsterdam University Press FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Cover illustration: Studio Aszyk, London. Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 713 5 e-isbn 978 90 4853 865 2 doi 10.5117/9789462987135 nur 670 © D. Strutt / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2019 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Contents Acknowledgements 7 1. Cinema’s Foundational Frissons 9 The Arrival of the Digital Image at the Station 9 A Futurist Cinema of Attractions 13 What is Post about Post-Cinema? 21 But is it Art? 26 From Cine-thinking to Digi-thinking 30 Technology and Reality 34 2. The Affective Synthesis of Reality by Digital Images 41 A Great Evolution 42 A Question of Cause and Responsibility 44 Cinema and Affection 48 Passive Synthesis and the Spiritual Automaton 51 Do We Need a New ‘Digital’ Image Type – A ‘Cinema 3’? 58 The Digital Revealing of Reality 60 Interstellar’s Ontological Revealing 64 The Digital Pharmakon 67 Plasticity and Politics 72 3. -

Plant Medicines, Healing and Psychedelic Science Cultural Perspectives Plant Medicines, Healing and Psychedelic Science Beatriz Caiuby Labate • Clancy Cavnar Editors

Beatriz Caiuby Labate · Clancy Cavnar Editors Plant Medicines, Healing and Psychedelic Science Cultural Perspectives Plant Medicines, Healing and Psychedelic Science Beatriz Caiuby Labate • Clancy Cavnar Editors Plant Medicines, Healing and Psychedelic Science Cultural Perspectives Editors Beatriz Caiuby Labate Clancy Cavnar East-West Psychology Program Psychiatric Alternatives California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS) San Francisco, California, USA San Francisco, CA, USA Center for Research and Post Graduate Studies in Social Anthropology (CIESAS) Guadalajara, Mexico ISBN 978-3-319-76719-2 ISBN 978-3-319-76720-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76720-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018935154 © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Irreversible É

IRREVERSIBLEé regia Gaspar Noé con Monica Bellucci, Vincent Cassel, Albert Dupontel, Jo Prestia, Philippe Nahon, Stéphane Drouot sceneggiatura Gaspar Noé fotografia Benoit Debie, Gaspar Noé montaggio Gaspar Noé scenografia Alain Juteau costumi Laure Culkovic musica Thomas Bangalter produzione Christophe Rossignon distribuzione Bim durata 1h30m Francia 2002 La trama: Alex e Marcus sono una bella coppia parigina che vive intensamente la loro giovane relazione. Sono rimasti in amicizia con Pierre, ex della donna, con cui amano incontrarsi spesso. All'uscita da una festa a casa di amici, Alex viene brutalmente aggredita e violentata da uno sconosciuto in un sotto- passaggio pedonale. Marcus e Pierre, accecati dalla rabbia e dalla sete di vendetta, decidono di mettersi sulle tracce dell'aggressore in cerca di giustizia sommaria. Il regista: Figlio del celebre pittore argentino Luis Felipe Noé, Gaspar Noé nasce a Buenos Aires nel 1963. E' attivo in Francia come montatore, fotografo, sceneggiatore e regista. Il suo primo corto è Tintarella di luna ('85), mentre debutta nel lungometraggio con Carne ('91). Nel 1998 segue Seul contre tous. Dopo Irréversible, dirige nel 2006 una parte del film collettivo Destricted, seguito nel 2008 da un altro film collettivo 8. Con il suo ultimo lungometraggio Enter the void ('09), è di nuovo in concorso a Cannes. Il film: Irréversible perchè il tempo distrugge tutto, perchè certe azioni sono irreparabili, perchè l'uomo è un animale, perchè il desiderio di vendetta è una pulsione naturale, perchè la maggior parte dei crimini resta impunita, perchè la perdita della persona amata distrugge come un fulmine, perchè l'amore è una fonte di vita, perchè la storia è tutta scritta con lo sperma e con il sangue, perchè le premonizioni non cambiano il corso delle cose, perchè il tempo rivela tutto il peggio e il meglio. -

READING the RAZOR BLADE the Problematic Reception of Contemporary French Extreme Cinema

READING THE RAZOR BLADE The Problematic Reception of Contemporary French Extreme Cinema MARTIN JOHN ANTHONY PARSONS Dissertation submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Masters by Research in French September 2013 CONTENTS Abstract...................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements.................................................................................................... 3 Introduction................................................................................................................ 4 Chapter 1: Friction...................................................................................................... 24 A Required Viewing Mode....................................................................................... 24 Friction..................................................................................................................... 28 A Statement of Intent: Carne................................................................................... 29 Whose Irresponsibility?: Seul contre tous................................................................ 36 Forwards, Backwards and Outwards: Irréversible……………………………………………… 40 Critical Mass……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 44 Chapter 2: Collision..................................................................................................... 47 Subversion.............................................................................................................. -

Lumière Festival2016

LUMIÈRE FESTIVAL2016 WELCOME CATHERINE DENEUVE LUMIÈRE AWARD 2016 The program! From Saturday 8 to Sunday 16 October © Patrick Swirc - Modds Swirc © Patrick WELCOME to the Lumière festival! AM R G PRO E H Invitations to actresses and T actors, filmmakers, film music composers. RETROSPECTIVES Restored prints on the big screen in the theater: See films Catherine Deneuve: Lumière Award 2016 Buster Keaton, Part 1 in optimal conditions. An iconic incarnation of the accomplished actress and movie Inventive, a daredevil, touching, hilarious, Buster Keaton was star, this extraordinary actress shook up the art of the actor, all of these things at once, and revolutionized burlesque Huge film screenings at inspired filmmakers for five decades, through her amazing, comedy ofthe early 20th century, during the same era as the Halle Tony Garnier, the daring filmography, exploring all genres and forms. Films« carte Charlie Chaplin. His introverted but reckless character, forever Auditorium of Lyon and the Lyon blanche» (personal picks), a master class and presentation impassible and searching for love, would bring him great of the Lumière Award. notoriety. The Keaton Project, led by the Bologna Film Library Conference Center. and Cohen Films, allows us to dive into his work, currently Marcel Carné under restoration. Silent films accompanied by music to A discovery of silent films with Marcel Carné contributed some of his most successful films to discover with the whole family. cinema concerts. the cinema and invented poetic realism with Jacques Prévert. In his body of work, we come across Jean Gabin, Michèle Quentin Tarantino: 1970 Morgan, Louis Jouvet, Arletty, Simone Signoret, then rediscover Three years after receiving the Lumière Award, the cinephile Buster Keaton in The Cameraman Master classes and the opportunity to attend special Jacques Brel, Annie Girardot or Maurice Ronet.