Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corrupting Photography Kerry Brougher

Corrupting Photography Kerry Brougher Joel Sternfeld’s 1979 photograph made in Woodland ,Washington seems at first to be merely a country road sweeping through a rather nondescript landscape. Then you're pulled further in through the images of a parked sheriffs car and bystanders in the road, staring at some kind of activity; there, at the point where the road stripes and telephone lines converge in a demonstration of renaissance perspective, lies a wet grey-brown mass—an elephant that has collapsed on the highway. Seen at a distance, the runaway beast, which could seems so incongruous or even surreal in this context, becomes merely one elements of the overall scene a prospect among many. The landscape, spotted with sheds, weeds, and rather ragged pine trees, seems as drained of energy and miserable as the elephant, it's Edenic beauty spoiled by encroaching development. “Exhausted Renegade Elephant, Woodland, Washington June 1979” first appeared in Joel Sternfeld's landmark photographic book American Prospects. Revealing much about the contemporary landscape in the American psyche both then and now, the 1987 publication depicts an exhausted garden ruins by unchecked growth, where troubling situations are camouflaged as the norm—a place unable to escape the phone circus-like behavior. Throughout the book, America lies collapsed in the middle of the road it cannot stop building. However, as an American photography from Carlton Watkins to Ansel Adams is inextricably bound with the landscape, American Prospects it's a book not just about the countries complex and troubled relationship to nature, but about photography itself. Its publication wasn't part a response to a dilemma facing many photographers in the 1970s who found themselves, like Sternfeld’s elephant, exhausted on a highway looking for a way forward. -

We Went to No Man's Land: Women Artists from the Rubell Family Collection

We Went to No Man’s Land: Women Artists from The Rubell Family Collection 12/22/15, 11:06 AM About Features AFC Editions Donate Sound of Art Search Art F City We Went to No Man’s Land: Women Artists from The Rubell Family Collection by Paddy Johnson and Michael Anthony Farley on December 21, 2015 We Went To... Like 6 Tweet Mai-Thu Perret with Ligia Dias, “Apocalypse Ballet (Pink Ring) and “Apocalypse Ballet (3 White Rings,” steel, wire, papier-mâché, emulsion paint, varnish, gouache, wig, flourescent tubes, viscose dress and leather belt, 2006. No Man’s Land: Women Artists from The Rubell Family Collection 95 NW 29 ST, Miami, FL 33127, U.S.A. through May 28, 2016 Participating artists: Michele Abeles, Nina Chanel Abney, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Kathryn Andrews, Janine Antoni, Tauba Auerbach, Alisa Baremboym, Katherine Bernhardt, Amy Bessone, Kerstin Bratsch, Cecily Brown, Iona Rozeal Brown, Miriam Cahn, Patty Chang, Natalie Czech, Mira Dancy, DAS INSTITUT, Karin Davie, Cara Despain, Charlotte Develter, Rineke Dijkstra, Thea Djordjadze, Nathalie Djurberg, Lucy Dodd, Moira Dryer, Marlene Dumas, Ida Ekblad, Loretta Fahrenholz, Naomi Fisher, Dara Friedman, Pia Fries, Katharina Fritsch, Isa Genzken, Sonia Gomes, Hannah Greely, Renée Green, Aneta Grzeszykowska, Jennifer Guidi, Rachel Harrison, Candida Höfer, Jenny Holzer, Cristina Iglesias, Hayv Kahraman, Deborah Kass, Natasja Kensmil, Anya Kielar, Karen Kilimnik, Jutta Koether, Klara Kristalova, Barbara Kruger, Yayoi Kusama, Sigalit Landau, Louise Lawler, Margaret Lee, Annette Lemieux, Sherrie Levine, Li Shurui, Sarah Lucas, Helen Marten, Marlene McCarty, Suzanne McClelland, Josephine Meckseper, Marilyn Minter, Dianna Molzan, Kristen Morgin, Wangechi Mutu, Maria Nepomuceno, Ruby Neri, Cady Noland, Katja Novitskoval Catherine Opie, Silke Otto-Knapp, Laura Owens, Celia Paul, Mai-Thu Perret, Solange Pessoa, Elizabeth Peyton, R.H. -

1997 Sundance Film Festival Awards Jurors

1997 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL The 1997 Sundance Film Festival continued to attract crowds, international attention and an appreciative group of alumni fi lmmakers. Many of the Premiere fi lmmakers were returning directors (Errol Morris, Tom DiCillo, Victor Nunez, Gregg Araki, Kevin Smith), whose earlier, sometimes unknown, work had received a warm reception at Sundance. The Piper-Heidsieck tribute to independent vision went to actor/director Tim Robbins, and a major retrospective of the works of German New-Wave giant Rainer Werner Fassbinder was staged, with many of his original actors fl own in for forums. It was a fi tting tribute to both Fassbinder and the Festival and the ways that American independent cinema was indeed becoming international. AWARDS GRAND JURY PRIZE JURY PRIZE IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Documentary—GIRLS LIKE US, directed by Jane C. Wagner and LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY (O SERTÃO DAS MEMÓRIAS), directed by José Araújo Tina DiFeliciantonio SPECIAL JURY AWARD IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Dramatic—SUNDAY, directed by Jonathan Nossiter DEEP CRIMSON, directed by Arturo Ripstein AUDIENCE AWARD JURY PRIZE IN SHORT FILMMAKING Documentary—Paul Monette: THE BRINK OF SUMMER’S END, directed by MAN ABOUT TOWN, directed by Kris Isacsson Monte Bramer Dramatic—HURRICANE, directed by Morgan J. Freeman; and LOVE JONES, HONORABLE MENTIONS IN SHORT FILMMAKING directed by Theodore Witcher (shared) BIRDHOUSE, directed by Richard C. Zimmerman; and SYPHON-GUN, directed by KC Amos FILMMAKERS TROPHY Documentary—LICENSED TO KILL, directed by Arthur Dong Dramatic—IN THE COMPANY OF MEN, directed by Neil LaBute DIRECTING AWARD Documentary—ARTHUR DONG, director of Licensed To Kill Dramatic—MORGAN J. -

Books Keeping for Auction

Books Keeping for Auction - Sorted by Artist Box # Item within Box Title Artist/Author Quantity Location Notes 1478 D The Nude Ideal and Reality Photography 1 3410-F wrapped 1012 P ? ? 1 3410-E Postcard sized item with photo on both sides 1282 K ? Asian - Pictures of Bruce Lee ? 1 3410-A unsealed 1198 H Iran a Winter Journey ? 3 3410-C3 2 sealed and 1 wrapped Sealed collection of photographs in a sealed - unable to 1197 B MORE ? 2 3410-C3 determine artist or content 1197 C Untitled (Cover has dirty snowman) ? 38 3410-C3 no title or artist present - unsealed 1220 B Orchard Volume One / Crime Victims Chronicle ??? 1 3410-L wrapped and signed 1510 E Paris ??? 1 3410-F Boxed and wrapped - Asian language 1210 E Sputnick ??? 2 3410-B3 One Russian and One Asian - both are wrapped 1213 M Sputnick ??? 1 3410-L wrapped 1213 P The Banquet ??? 2 3410-L wrapped - in Asian language 1194 E ??? - Asian ??? - Asian 1 3410-C4 boxed wrapped and signed 1180 H Landscapes #1 Autumn 1997 298 Scapes Inc 1 3410-D3 wrapped 1271 I 29,000 Brains A J Wright 1 3410-A format is folded paper with staples - signed - wrapped 1175 A Some Photos Aaron Ruell 14 3410-D1 wrapped with blue dot 1350 A Some Photos Aaron Ruell 5 3410-A wrapped and signed 1386 A Ten Years Too Late Aaron Ruell 13 3410-L Ziploc 2 soft cover - one sealed and one wrapped, rest are 1210 B A Village Destroyed - May 14 1999 Abrahams Peress Stover 8 3410-B3 hardcovered and sealed 1055 N A Village Destroyed May 14, 1999 Abrahams Peress Stover 1 3410-G Sealed 1149 C So Blue So Blue - Edges of the Mediterranean -

Notable Photographers Updated 3/12/19

Arthur Fields Photography I Notable Photographers updated 3/12/19 Walker Evans Alec Soth Pieter Hugo Paul Graham Jason Lazarus John Divola Romuald Hazoume Julia Margaret Cameron Bas Jan Ader Diane Arbus Manuel Alvarez Bravo Miroslav Tichy Richard Prince Ansel Adams John Gossage Roger Ballen Lee Friedlander Naoya Hatakeyama Alejandra Laviada Roy deCarava William Greiner Torbjorn Rodland Sally Mann Bertrand Fleuret Roe Etheridge Mitch Epstein Tim Barber David Meisel JH Engstrom Kevin Bewersdorf Cindy Sherman Eikoh Hosoe Les Krims August Sander Richard Billingham Jan Banning Eve Arnold Zoe Strauss Berenice Abbot Eugene Atget James Welling Henri Cartier-Bresson Wolfgang Tillmans Bill Sullivan Weegee Carrie Mae Weems Geoff Winningham Man Ray Daido Moriyama Andre Kertesz Robert Mapplethorpe Dawoud Bey Dorothea Lange uergen Teller Jason Fulford Lorna Simpson Jorg Sasse Hee Jin Kang Doug Dubois Frank Stewart Anna Krachey Collier Schorr Jill Freedman William Christenberry David La Spina Eli Reed Robert Frank Yto Barrada Thomas Roma Thomas Struth Karl Blossfeldt Michael Schmelling Lee Miller Roger Fenton Brent Phelps Ralph Gibson Garry Winnogrand Jerry Uelsmann Luigi Ghirri Todd Hido Robert Doisneau Martin Parr Stephen Shore Jacques Henri Lartigue Simon Norfolk Lewis Baltz Edward Steichen Steven Meisel Candida Hofer Alexander Rodchenko Viviane Sassen Danny Lyon William Klein Dash Snow Stephen Gill Nathan Lyons Afred Stieglitz Brassaï Awol Erizku Robert Adams Taryn Simon Boris Mikhailov Lewis Baltz Susan Meiselas Harry Callahan Katy Grannan Demetrius -

New York Times July 15, 2003 'Critic's Notebook: for London, a Summer

New York Times July 15, 2003 ‘Critic's Notebook: For London, a Summer of Photographic Memory; Around the City, Images From Around the World’ Michael Kimmelman This city is immersed in photography exhibitions, a coincidence of scheduling, perhaps, that the museums here decided made a catchy marketing scheme. Posters and flyers advertise the “Summer of Photography.” Why not? I stopped here on the way home from the Venice Biennale, after which any exhibition that did not involve watching hours of videos in plywood sweatboxes seemed like a joy. The London shows leave you with no specific definition of what photography is now, except that it is, fruitfully, many things at once, which is a functionally vague description of the medium. You can nevertheless get a fairly clear idea of the differences between a good photograph and a bad one. In the first category are two unlike Americans: Philip-Lorca diCorcia, with a show at Whitechapel, and Cindy Sherman, at Serpentine. Into the second category falls Wolfgang Tillmans, the chic German-born, London-based photographer, who has an exhibition at Tate Britain that cheerfully disregards the idea that there might even be a difference between Categories 1 and 2. There is also the posthumous retrospective, long overdue, of Guy Bourdin, the high- concept soft-core-pornography fashion photographer for French Vogue and Charles Jourdan shoes in the 1970's and 80's, at the Victoria and Albert. And as the unofficial anchor for it all Tate Modern, which until now had apparently never organized a major photography show, has tried in one fell swoop to make up for lost time with “Cruel and Tender: The Real in the 20th Century Photograph.” The title is from Lincoln Kirstein's apt description of Walker Evans's work as “tender cruelty.” Like Tate Modern in general, “Cruel and Tender” is vast, not particularly logical and blithely skewed. -

Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci, with a Short Story by Jeffrey Eugenides

Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci, with a short story by Jeffrey Eugenides Author Marcoci, Roxana Date 2005 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art ISBN 0870700804 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/116 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art museumof modern art lIOJ^ArxxV^ 9 « Thomas Demand Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci with a short story by Jeffrey Eugenides The Museum of Modern Art, New York Published in conjunction with the exhibition Thomas Demand, organized by Roxana Marcoci, Assistant Curator in the Department of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 4-May 30, 2005 The exhibition is supported by Ninah and Michael Lynne, and The International Council, The Contemporary Arts Council, and The Junior Associates of The Museum of Modern Art. This publication is made possible by Anna Marie and Robert F. Shapiro. Produced by the Department of Publications, The Museum of Modern Art, New York Edited by Joanne Greenspun Designed by Pascale Willi, xheight Production by Marc Sapir Printed and bound by Dr. Cantz'sche Druckerei, Ostfildern, Germany This book is typeset in Univers. The paper is 200 gsm Lumisilk. © 2005 The Museum of Modern Art, New York "Photographic Memory," © 2005 Jeffrey Eugenides Photographs by Thomas Demand, © 2005 Thomas Demand Copyright credits for certain illustrations are cited in the Photograph Credits, page 143. Library of Congress Control Number: 2004115561 ISBN: 0-87070-080-4 Published by The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York, New York 10019-5497 (www.moma.org) Distributed in the United States and Canada by D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, New York Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Thames & Hudson Ltd., London Front and back covers: Window (Fenster). -

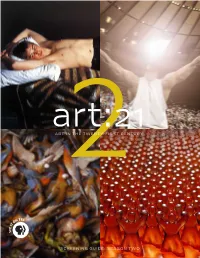

Art in the Twenty-First Century Screening Guide: Season

art:21 ART IN2 THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY SCREENING GUIDE: SEASON TWO SEASON TWO GETTING STARTED ABOUT THIS SCREENING GUIDE ABOUT ART21, INC. This screening guide is designed to help you plan an event Art21, Inc. is a non-profit contemporary art organization serving using Season Two of Art in the Twenty-First Century. This guide students, teachers, and the general public. Art21’s mission is to includes a detailed episode synopsis, artist biographies, discussion increase knowledge of contemporary art, ignite discussion, and inspire questions, group activities, and links to additional resources online. creative thinking by using diverse media to present contemporary artists at work and in their own words. ABOUT ART21 SCREENING EVENTS Public screenings of the Art:21 series engage new audiences and Art21 introduces broad public audiences to a diverse range of deepen their appreciation and understanding of contemporary art contemporary visual artists working in the United States today and and ideas. Organizations and individuals are welcome to host their to the art they are producing now. By making contemporary art more own Art21 events year-round. Some sites plan their programs for accessible, Art21 affords people the opportunity to discover their broad public audiences, while others tailor their events for particular own innate abilities to understand contemporary art and to explore groups such as teachers, museum docents, youth groups, or scholars. possibilities for new viewpoints and self-expression. Art21 strongly encourages partners to incorporate interactive or participatory components into their screenings, such as question- The ongoing goals of Art21 are to enlarge the definitions and and-answer sessions, panel discussions, brown bag lunches, guest comprehension of contemporary art, to offer the public a speakers, or hands-on art-making activities. -

“Highlights of a Trip to Hell” Contextualizing the Initial

“Highlights Of A Trip To Hell” Contextualizing the Initial Reception of Larry Clark’s Tulsa by William T. Green A thesis project presented to Ryerson University and George Eastman House, Intentional Museum of Photography in Film In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the program of Photographic Preservation and Collections Management Rochester, New York, United States and Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © William T. Green 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. William T. Green I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. William T. Green ii Abstract Released in 1971, Tulsa, American artist Larry Clark’s career-launching first photobook, is today remembered as marking a watershed moment in American photography. This paper travels back to the era that Tulsa was first published to examine the book’s initial critical reception and significance within that specific cultural and artistic climate. It presents an abbreviated overview of Tulsa’s gradual creation; illustrates the ways in which the book was both similar to and different from other commonly cited contemporaneous works; and surveys its evolving status and reputation throughout the 1970s and into the early 1980s, when its second edition was published. -

NGA | 2017 Annual Report

N A TIO NAL G ALL E R Y O F A R T 2017 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Board of Trustees COMMITTEE Buffy Cafritz (as of September 30, 2017) Frederick W. Beinecke Calvin Cafritz Chairman Leo A. Daly III Earl A. Powell III Louisa Duemling Mitchell P. Rales Aaron Fleischman Sharon P. Rockefeller Juliet C. Folger David M. Rubenstein Marina Kellen French Andrew M. Saul Whitney Ganz Sarah M. Gewirz FINANCE COMMITTEE Lenore Greenberg Mitchell P. Rales Rose Ellen Greene Chairman Andrew S. Gundlach Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary of the Treasury Jane M. Hamilton Richard C. Hedreen Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Helen Lee Henderson Chairman President David M. Rubenstein Kasper Andrew M. Saul Mark J. Kington Kyle J. Krause David W. Laughlin AUDIT COMMITTEE Reid V. MacDonald Andrew M. Saul Chairman Jacqueline B. Mars Frederick W. Beinecke Robert B. Menschel Mitchell P. Rales Constance J. Milstein Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Pappajohn Sally Engelhard Pingree David M. Rubenstein Mitchell P. Rales David M. Rubenstein Tony Podesta William A. Prezant TRUSTEES EMERITI Diana C. Prince Julian Ganz, Jr. Robert M. Rosenthal Alexander M. Laughlin Hilary Geary Ross David O. Maxwell Roger W. Sant Victoria P. Sant B. Francis Saul II John Wilmerding Thomas A. Saunders III Fern M. Schad EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Leonard L. Silverstein Frederick W. Beinecke Albert H. Small President Andrew M. Saul John G. Roberts Jr. Michelle Smith Chief Justice of the Earl A. Powell III United States Director Benjamin F. Stapleton III Franklin Kelly Luther M. -

Liz Deschenes

MIGUEL ABREU GALLERY LIZ DESCHENES Born in Boston, MA, 1966 Lives and works in New York EDUCATION 1988 Rhode Island School of Design B.F.A. Photography, Providence, RI SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2016 Campoli Presti, Paris, France Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, MA 2015 Gallery 4.1.1, MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA 2014 Gallery 7, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN Stereographs #1-4 (Rise / Fall), Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York 2013 Bracket (Paris), Campoli Presti, Paris, France Bracket (London), Campoli Presti, London, UK 2012 Secession, Vienna, Austria 2010 Shift / Rise, Sutton Lane, Brussels, Belgium 2009 Right / Left, Sutton Lane, Paris, France Chromatic Aberration (Red Screen, Green Screen, Blue Screen - a series of photographs from 2001 - 2008), Sutton Lane, London, UK Tilt / Swing, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York 2007 Photographs, Sutton Lane, London, UK Registration, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York 2001 Blue Screen Process, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York 1999 Below Sea Level, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York 1997 Beppu, Bronwyn Keenan Gallery, New York 88 Eldridge Street / 36 Orchard Street, New York, NY 10002 • 212.995.1774 • fax 646.688.2302 [email protected] • www.miguelabreugallery.com SELECTED GROUP & TWO-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2017 Sol Lewitt & Liz Deschenes, Fraenkel Gallery, San Fransisco, CA PhotoPlay: Lucid Objects, Paris Photo, Grand Palais, Paris, France The Coffins of Paa Joe and the Pursuit of Happiness, The School | Jack Shainman Gallery, Kinderhook, NY Paper as Object, curated by Richard Tinkler, Albert Merola Gallery, -

Larry Clark, Invité D'honneur

Communiqué de presse n°2 – Journées cinématographiques dionysiennes LARRY CLARK, INVITÉ D’HONNEUR DES 18es JOURNÉES CINÉMATOGRAPHIQUES DIONYSIENNES Larry Clark © Javier Ortega 18 ans, et toujours REBEL REBEL ! Les Journées cInématographiques dionysIennes revIennent du 7 au 13 févrIer 2018 au cinéma L’Écran de Saint-Denis (93). Pour cette 18e édition intitulée REBEL REBEL, elles dresseront un grand panorama de la rébellion à l'écran, avec plus de soixante-dix films (inédits, avant-premières, classiques) et de nombreuses rencontres en présence de cinéastes, critiques ou membres de la société civile. Le photographe et réalIsateur amérIcaIn LARRY CLARK sera l’InvIté d’honneur. Il accompagnera une rétrospectIve de ses fIlms (Kids, Bully, Ken Park, Wassup Rockers...), ainsi que ses deux derniers fIlms Inédits tournés en toute indépendance, Marfa Girls 1 & 2, et un long métrage surprIse. Pour clore en musique cette édItIon de la majorIté, les Journées cinématographiques dionysIennes REBEL REBEL accueilleront les musIcIens de Wassup Rockers pour un concert final. www.dIonysIennes.org RelatIon Presse : Géraldine Cance - 06 60 13 11 00 - [email protected] LARRY CLARK, INVITÉ D’HONNEUR « De ses clichés noir et blanc du début des années 1960 aux longs métrages qu’il réalise depuis 1995 tels que Kids (1995), Bully (2001) ou Ken Park (2002), Larry Clark, internationalement reconnu pour son travail, traduit sans concession la perte de repères et les dérives de l’adolescence. » Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, lors de la première rétrospective de ses photographies en France, en 2010. Le photographe et réalisateur Larry Clark est né en 1943 à Tulsa aux États-Unis.