LARGE PRINT the ARCADES Contemporary Art and Walter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” an Intergenerational Exhibition of Works from Thirty-Seven Artists, Conceived by Curator Okwui Enwezor

NEW MUSEUM PRESENTS “GRIEF AND GRIEVANCE: ART AND MOURNING IN AMERICA,” AN INTERGENERATIONAL EXHIBITION OF WORKS FROM THIRTY-SEVEN ARTISTS, CONCEIVED BY CURATOR OKWUI ENWEZOR Exhibition Brings Together Works that Address Black Grief as a National Emergency in the Face of a Politically Orchestrated White Grievance New York, NY...The New Museum is proud to present “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” an exhibition originally conceived by Okwui Enwezor (1963-2019) for the New Museum, and presented with curatorial support from advisors Naomi Beckwith, Massimiliano Gioni, Glenn Ligon, and Mark Nash. On view from February 17 to June 6, 2021, “Grief and Grievance” is an intergenerational exhibition bringing together thirty-seven artists working in a variety of mediums who have addressed the concept of mourning, commemoration, and loss as a direct response to the national emergency of racist violence experienced by Black communities across America. The exhibition further considers the intertwined phenomena of Black grief and a politically orchestrated white grievance, as each structures and defines contemporary American social and political life. Included in “Grief and Grievance” are works encompassing video, painting, sculpture, installation, photography, sound, and performance made in the last decade, along with several key historical works and a series of new commissions created in response to the concept of the exhibition. The artists on view will include: Terry Adkins, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kevin Beasley, Dawoud Bey, Mark -

In Conversation with Adam Pendleton: What Is Black Dada?

In conversation with Adam Pendleton: What is Black Dada? Awa Konaté James Baldwin once said, ‘we used to think of history as the realm of the settled as an inalterable past, as a nightmare. That was the legacy bequeathed us by the past century’s catastrophes. But while we can never redeem what has been lost, versions of the past are forever being reconstructed in our fabrication of the present.’1 Although Baldwin enumerated these words in 1972, today’s volatile political moments and relations reminds us that the past is repeatedly embedded, and evermore so, in our present sphere. Baldwin comments on the interrelations between past and present realities as a continuum of cultural and historical notions that constitute the very materiality of our social fabric as ever persistent, suggesting the past is never past but an ongoing rupture in the present. Adam Pendleton is an artist whose unwinnable and complex layered practice is exceptionally occupied with Baldwin’s declarative statement. With a career spanning nearly two decades, Pendleton has situated the intersections of race, belonging, cultural politics and art history as varying constructions that are rearticulated and imposed in the very centre of our ‘Contemporary’ – not merely in order to inquire ‘how’ and ‘what if’ but to push the very logic that constitutes their historical and social functions. My first encounter with Adam Pendleton was his large ‘Black Lives’ banner at the Venice Biennale’s Belgian pavilion in 2015.2 The context was stupendous, the banner’s dominating and large scaled presence appeared to almost ‘devour’ the white cubed pavilion by forcing the centrality of its race relations. -

We Went to No Man's Land: Women Artists from the Rubell Family Collection

We Went to No Man’s Land: Women Artists from The Rubell Family Collection 12/22/15, 11:06 AM About Features AFC Editions Donate Sound of Art Search Art F City We Went to No Man’s Land: Women Artists from The Rubell Family Collection by Paddy Johnson and Michael Anthony Farley on December 21, 2015 We Went To... Like 6 Tweet Mai-Thu Perret with Ligia Dias, “Apocalypse Ballet (Pink Ring) and “Apocalypse Ballet (3 White Rings,” steel, wire, papier-mâché, emulsion paint, varnish, gouache, wig, flourescent tubes, viscose dress and leather belt, 2006. No Man’s Land: Women Artists from The Rubell Family Collection 95 NW 29 ST, Miami, FL 33127, U.S.A. through May 28, 2016 Participating artists: Michele Abeles, Nina Chanel Abney, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Kathryn Andrews, Janine Antoni, Tauba Auerbach, Alisa Baremboym, Katherine Bernhardt, Amy Bessone, Kerstin Bratsch, Cecily Brown, Iona Rozeal Brown, Miriam Cahn, Patty Chang, Natalie Czech, Mira Dancy, DAS INSTITUT, Karin Davie, Cara Despain, Charlotte Develter, Rineke Dijkstra, Thea Djordjadze, Nathalie Djurberg, Lucy Dodd, Moira Dryer, Marlene Dumas, Ida Ekblad, Loretta Fahrenholz, Naomi Fisher, Dara Friedman, Pia Fries, Katharina Fritsch, Isa Genzken, Sonia Gomes, Hannah Greely, Renée Green, Aneta Grzeszykowska, Jennifer Guidi, Rachel Harrison, Candida Höfer, Jenny Holzer, Cristina Iglesias, Hayv Kahraman, Deborah Kass, Natasja Kensmil, Anya Kielar, Karen Kilimnik, Jutta Koether, Klara Kristalova, Barbara Kruger, Yayoi Kusama, Sigalit Landau, Louise Lawler, Margaret Lee, Annette Lemieux, Sherrie Levine, Li Shurui, Sarah Lucas, Helen Marten, Marlene McCarty, Suzanne McClelland, Josephine Meckseper, Marilyn Minter, Dianna Molzan, Kristen Morgin, Wangechi Mutu, Maria Nepomuceno, Ruby Neri, Cady Noland, Katja Novitskoval Catherine Opie, Silke Otto-Knapp, Laura Owens, Celia Paul, Mai-Thu Perret, Solange Pessoa, Elizabeth Peyton, R.H. -

BEYOND WORDS Incorporating Collage, Cultural Criticism, Poetry and Video, Adam Pendleton’S Work Defies Categorization

the exchange aRt TALK BEYOND WORDS Incorporating collage, cultural criticism, poetry and video, Adam Pendleton’s work defies categorization. That’s only part of what makes it so appealing to collectors and museums alike. BY TED LOOS PHOTOGRAPHY BY CARLOS CHAVARRÍA HEN AN ARTIST captures a cultural he writes. Pendleton doesn’t think he invented the Being gay and black gave him a useful outsider’s moment just so, it’s like a lightning conversation that he’s a part of. “It is a continuum,” he perspective. “When you’re sort of off to the side, you bolt—there’s a crackle in the air, a blind- says, “but it doesn’t only move forward; it moves back- supply yourself with something that long term is ing flash, and the clouds part. At just 34, wards and sideways, too.” ultimately more productive,” he says. (Pendleton is WBrooklyn-based artist Adam Pendleton has proved Though he works in many media, much of his now married to a food entrepreneur, and they live in himself capable of generating such phenomena. visual work starts as collage, and he has a canny eye Brooklyn’s Fort Greene.) Over the past decade, Pendleton’s conceptual take for juxtapositions that recalls one of his idols, Jasper In 2002, he completed a two-year independent art- on race in America has drawn attention and stirred Johns. “Already in his incredibly youthful career, he ist’s study program in Pietrasanta, Italy, but he doesn’t discussion across the country. Last year, he had solo has managed to land on a graphic language that is have a bachelor’s degree or an M.F.A. -

Ashley and Mary-Kate Olsen Hosted the 2...Ia Art Foundation's Fall Night

Ashley and Mary-Kate Olsen Hosted the 2019 Dia Art Foundation’s Fall Night BY ZACHARY SCHWARTZ November 18, 2019 Ashley and Mary-Kate Olsen Photo: BFA / Sansho Scott On a nippy November night that felt more like December, the Dia Art Foundation invited gallerists, artists, and fashionable art patrons to their annual Fall Night. Mary- Kate and Ashley Olsen chaired the chic festivity, along with Rashid Johnson, Schmidt Campbell, and Melvin Edwards. The party’s primary goal was to support the Dia Art Foundation and it was particularly exciting to celebrate the evening’s honoree, Sam Gilliam. Gilliam currently has an exhibition at Dia Beacon, a perfect venue for his 1960s operatic painted canvases. Hosted in a Chelsea warehouse and supported by The Row, the Dia Art Foundation’s Fall Night started with a joyous cocktail hour, where black cocktail dresses mingled with sharply tailored suits. An impressive roster of artists arrived at the event, including Lawrence Weiner, Adam Pendleton, Marilyn Minter, Melvin Edwards, and Ursula von Rydingsvard. The dark, raw space was perfect for a night out with friends; the dim lighting offered privacy for clusters of attendees who so desired it. The artists in attendance socialized with guests like Sandra Brant, Thelma Golden, Arne Glimcher, Agnes Gund, Jessica Joffe, and Stefano Tonchi. The guest list was a testament to the crowds that Dia, Gilliam, and the Olsen twins can draw. Cocktails were followed by dinner, laid out with seven gorgeous long tables laden with multi-leveled candles. The seated dinner resembled a family-style Thanksgiving supper with butternut squash, brussels sprouts, and roasted chicken. -

Adam by Pendleton Venus Williams

Interview Magazine Williams, Venus: Adam Pendleton Summer 2021 THIS PAGE: Photographed by Styled by T-shirt (worn ANDY JERMAINE throughout) by JACKSON DALEY CDLP Necklace by TIFFANY & CO. OPPOSITE PAGE: Jacket and Pants by DIOR MEN Necklace by BVLGARI Adam Pendleton by “Always try something different, always do something new.” Venus112 Williams Coat, Jacket, Pants, and Shoes by 5 MONCLER CRAIG GREEN ADAM PENDLETON No contemporary artist embodies the spirit of Walt Whitman’s declaration “I contain multitudes” more potently than Adam Pendleton. Across his bold, compressed, densely piled surfaces spill words, fragments, rally cries, commands, defiant chants, civic demands, graffiti, broken poetic syllables, and blown-apart letters, all competing in a visual-linguistic cacophony that feels like a snapshot of our loud nation in the present tense. The 37-year-old, New York– based artist is a prodigious talent whose multidisciplinary corpus ranges from performance to photography, but he is particularly celebrated for his graphic, black-and-white screen-print paintings, sometimes covering entire walls, collaged and layered with so much visual complexity that they often take on the dimensionality of sculpture. In the past two decades, Pendleton has built a career that bridges so many seemingly incompatible realms—formalism with political activism, the visceral energy of abstract painting with hyper-tuned socio-historic concerns, the living messages of grassroots movements such as Black Lives Matter inside the institutional structure of galleries and museums. The artist seems almost single-handedly to be redefining the role of the artist for our current age. This past spring, Pendleton’s alchemy filled the lobby of New York’s New Museum with paintings of protest language and images of masks stamped directly on the walls. -

Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci, with a Short Story by Jeffrey Eugenides

Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci, with a short story by Jeffrey Eugenides Author Marcoci, Roxana Date 2005 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art ISBN 0870700804 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/116 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art museumof modern art lIOJ^ArxxV^ 9 « Thomas Demand Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci with a short story by Jeffrey Eugenides The Museum of Modern Art, New York Published in conjunction with the exhibition Thomas Demand, organized by Roxana Marcoci, Assistant Curator in the Department of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 4-May 30, 2005 The exhibition is supported by Ninah and Michael Lynne, and The International Council, The Contemporary Arts Council, and The Junior Associates of The Museum of Modern Art. This publication is made possible by Anna Marie and Robert F. Shapiro. Produced by the Department of Publications, The Museum of Modern Art, New York Edited by Joanne Greenspun Designed by Pascale Willi, xheight Production by Marc Sapir Printed and bound by Dr. Cantz'sche Druckerei, Ostfildern, Germany This book is typeset in Univers. The paper is 200 gsm Lumisilk. © 2005 The Museum of Modern Art, New York "Photographic Memory," © 2005 Jeffrey Eugenides Photographs by Thomas Demand, © 2005 Thomas Demand Copyright credits for certain illustrations are cited in the Photograph Credits, page 143. Library of Congress Control Number: 2004115561 ISBN: 0-87070-080-4 Published by The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York, New York 10019-5497 (www.moma.org) Distributed in the United States and Canada by D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, New York Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Thames & Hudson Ltd., London Front and back covers: Window (Fenster). -

Art in the Twenty-First Century Screening Guide: Season

art:21 ART IN2 THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY SCREENING GUIDE: SEASON TWO SEASON TWO GETTING STARTED ABOUT THIS SCREENING GUIDE ABOUT ART21, INC. This screening guide is designed to help you plan an event Art21, Inc. is a non-profit contemporary art organization serving using Season Two of Art in the Twenty-First Century. This guide students, teachers, and the general public. Art21’s mission is to includes a detailed episode synopsis, artist biographies, discussion increase knowledge of contemporary art, ignite discussion, and inspire questions, group activities, and links to additional resources online. creative thinking by using diverse media to present contemporary artists at work and in their own words. ABOUT ART21 SCREENING EVENTS Public screenings of the Art:21 series engage new audiences and Art21 introduces broad public audiences to a diverse range of deepen their appreciation and understanding of contemporary art contemporary visual artists working in the United States today and and ideas. Organizations and individuals are welcome to host their to the art they are producing now. By making contemporary art more own Art21 events year-round. Some sites plan their programs for accessible, Art21 affords people the opportunity to discover their broad public audiences, while others tailor their events for particular own innate abilities to understand contemporary art and to explore groups such as teachers, museum docents, youth groups, or scholars. possibilities for new viewpoints and self-expression. Art21 strongly encourages partners to incorporate interactive or participatory components into their screenings, such as question- The ongoing goals of Art21 are to enlarge the definitions and and-answer sessions, panel discussions, brown bag lunches, guest comprehension of contemporary art, to offer the public a speakers, or hands-on art-making activities. -

Hauser & Wirth Announces Major Initiative to Raise Funds for Key

Press Release Hauser & Wirth Announces Major Initiative to Raise Funds for Key Visual Arts Organizations in New York City Impacted by the COVID-19 Pandemic Beginning early October, works by scores of artists will be sold to benefit 16 non-profit institutions and charitable partners New York…Hauser & Wirth co-presidents Iwan Wirth, Manuela Wirth, and Marc Payot, announced today that the gallery has organized ‘Artists for New York,’ a major initiative to raise funds in support of a group of pioneering non-profit visual arts organizations across New York City that have been profoundly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The project brings together dozens of works committed by foremost artists across generations, from both within and outside of the gallery’s program, that will be sold to benefit these institutions that have played a significant role in shaping the city’s rich cultural history and will play a critical role in its future recovery. The coronavirus pandemic has taken an unprecedented toll upon the arts in New York. Facing dire budget shortfalls for the 2020 fiscal year caused by necessary and prolonged closures during the pandemic, and expecting further impact upon earned income and contributed revenue in the year ahead, the city’s small and mid-scale institutions are extremely vulnerable at this moment. ‘Artists for New York’ will raise funds to support the recovery needs of fourteen of these organizations: Artists Space, The Bronx Museum of the Arts, Dia Art Foundation, The Drawing Center, El Museo del Barrio, High Line Art, MoMA PS1, New Museum, Public Art Fund, Queens Museum, SculptureCenter, The Studio Museum in Harlem, Swiss Institute, and White Columns. -

Liz Deschenes

MIGUEL ABREU GALLERY LIZ DESCHENES Born in Boston, MA, 1966 Lives and works in New York EDUCATION 1988 Rhode Island School of Design B.F.A. Photography, Providence, RI SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2016 Campoli Presti, Paris, France Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, MA 2015 Gallery 4.1.1, MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA 2014 Gallery 7, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN Stereographs #1-4 (Rise / Fall), Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York 2013 Bracket (Paris), Campoli Presti, Paris, France Bracket (London), Campoli Presti, London, UK 2012 Secession, Vienna, Austria 2010 Shift / Rise, Sutton Lane, Brussels, Belgium 2009 Right / Left, Sutton Lane, Paris, France Chromatic Aberration (Red Screen, Green Screen, Blue Screen - a series of photographs from 2001 - 2008), Sutton Lane, London, UK Tilt / Swing, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York 2007 Photographs, Sutton Lane, London, UK Registration, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York 2001 Blue Screen Process, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York 1999 Below Sea Level, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York 1997 Beppu, Bronwyn Keenan Gallery, New York 88 Eldridge Street / 36 Orchard Street, New York, NY 10002 • 212.995.1774 • fax 646.688.2302 [email protected] • www.miguelabreugallery.com SELECTED GROUP & TWO-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2017 Sol Lewitt & Liz Deschenes, Fraenkel Gallery, San Fransisco, CA PhotoPlay: Lucid Objects, Paris Photo, Grand Palais, Paris, France The Coffins of Paa Joe and the Pursuit of Happiness, The School | Jack Shainman Gallery, Kinderhook, NY Paper as Object, curated by Richard Tinkler, Albert Merola Gallery, -

Paris | London

Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin | Paris | London The Brooklyn Rail Biswas, Allie: in conversation: Adam Pendleton September 2016 maxhetzler.com Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin | Paris | London The Brooklyn Rail Biswas, Allie: in conversation: Adam Pendleton September 2016 Adam Pendleton with Allie Biswas Words are essential in Adam Pendleton’s art. The artist’s engagement with experimental prose and poetry over the past ten years, along with his cross-referencing of visual and social histories, has made space for new types of language within conceptual art. Pendleton’s largest U.S. museum show to date, Adam Pendleton: Becoming Imperceptible, opened at Contemporary Arts Center New Orleans in April, before traveling to the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, where it is on view through September 25. Allie Biswas (Rail): You made an instrumental move in getting your career off the ground by taking your art to galleries and making them look at it. There’s a story that your work was included in a show in New York at Installation view: Becoming Imperceptible, Contemporary Arts Center New Orleans, April 1 – June 1, 2016. Courtesy the artist. Gallery Onetwentyeight, the director of which assisted Sol LeWitt, and that’s how LeWitt saw your work. the religious aspect, but you leave the gospel music, the Adam Pendleton: Yes, that’s true. Those earlier works (al- musical component? What happens if you take out the most) always incorporated language, for one. Otherwise, religious language and put in language that’s related to there was a system to how the thing was composed. So queer activism or contemporary poetics? It was about I was convinced that, even though visually they looked creating a capacious space, breaking down one form and like abstract painting, they were very much conceptual. -

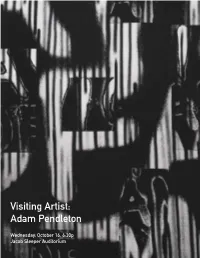

Visiting Artist: Adam Pendleton

Visiting Artist: Adam Pendleton Wednesday, October 16, 6:30p Jacob Sleeper Auditorium About the artist Adam Pendleton is an interdisciplinary artist whose work mines the histories of art and of social movements to create densely layered, conceptual works. Combining painting, silkscreen, collage, video, installation and performance, his broad output is united by a monochrome aesthetic and an engagement with the limits of meaning in both language and images. In his work, historical avant- garde strategies are recontextualized to address the black experience in America. Pendleton’s Black Dada, an ongoing interdisciplinary project in publishing, painting, installation and more, addresses the possibility of a new avant-garde language for African American experience. Pendleton poses urgent yet open-ended questions about the ownership of cultural history and the legacy of Modernism in the present. Pendleton has been the subject of solo exhibitions at the MIT List Visual Art Center in Cambridge; the Baltimore Museum of Art; the Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin; Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans; among many others. He studied at the Artspace Independent Study Program in Peitrasanta, Italy. He is represented by Pace Gallery. Works Writings “A Young Artist and Disrupter Plants His Flag for Black Lives” by Robin Pogrebin, New York Times, 2018 “Adam Pendleton Examines the Multiplicity of Blackness” by Diana Sette, Hyperallergic, 2017 “Black Dada Reader” by Adam Pendleton, 2017 Adam Pendleton in Conversation with Allie Biswas, Brooklyn Rail, 2016 “The Parallax View: The Art of Adam Pendleton” by Tom McDonough, Artforum, 2013 6/6/2019 A Young Artist and Disrupter Plants His Flag for Black Lives - The New York Times A Young Artist and Disrupter Plants His Flag for Black Lives By Robin Pogrebin May 3, 2018 When the unarmed teenager Trayvon Martin was killed in 2012, Florida’s self‑defense law known as Stand Your Ground became the subject of much public discussion, though it was ultimately not used in court to defend the shooter, George Zimmerman.