Kenosha Maroons: Never a Winning Game

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valuation of NFL Franchises

Valuation of NFL Franchises Author: Sam Hill Advisor: Connel Fullenkamp Acknowledgement: Samuel Veraldi Honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation with Distinction in Economics in Trinity College of Duke University Duke University Durham, North Carolina April 2010 1 Abstract This thesis will focus on the valuation of American professional sports teams, specifically teams in the National Football League (NFL). Its first goal is to analyze the growth rates in the prices paid for NFL teams throughout the history of the league. Second, it will analyze the determinants of franchise value, as represented by transactions involving NFL teams, using a simple ordinary-least-squares regression. It also creates a substantial data set that can provide a basis for future research. 2 Introduction This thesis will focus on the valuation of American professional sports teams, specifically teams in the National Football League (NFL). The finances of the NFL are unparalleled in all of professional sports. According to popular annual rankings published by Forbes Magazine (http://www.Forbes.com/2009/01/13/nfl-cowboys-yankees-biz-media- cx_tvr_0113values.html), NFL teams account for six of the world’s ten most valuable sports franchises, and the NFL is the only league in the world with an average team enterprise value of over $1 billion. In 2008, the combined revenue of the league’s 32 teams was approximately $7.6 billion, the majority of which came from the league’s television deals. Its other primary revenue sources include ticket sales, merchandise sales, and corporate sponsorships. The NFL is also known as the most popular professional sports league in the United States, and it has been at the forefront of innovation in the business of sports. -

Present Julius Hilltop Track Squad Competing General Staff Caesar Next Week in Penn Relay Carnival Reviews Unit

VOL. Ill GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, D. C, APRIL 27, 1922 No. 24 PRESENT JULIUS HILLTOP TRACK SQUAD COMPETING GENERAL STAFF CAESAR NEXT WEEK IN PENN RELAY CARNIVAL REVIEWS UNIT Mask and Bauble Club Will Give Georgetown Represented By a Score of Men In Track Classic—Bob Georgetown R. O. T. C. Makes Shakespearean Play On ' LeGendre To Defend Pentathlon Title Against Strong Good Showing In Rigid Test May 4 and 5. Field—Eight Relay Teams Entered. For College Rating. The Mask and Bauble Club, which was Following in excellent military fashion Georgetown's delegation to the Univer- blue and gray track followers expect behind the Third Cavalry Band from reorganized at Georgetown during the sity of Pennsylvania Relay Carnival, their favorite to experience no great Fort Myer the Georgetown University first part of the present school year, will which is to be held at Franklin Field, difficulty in winning. Reserve Officers Training Corps march- Philadelphia on Friday and Saturday of Georgetown will be represented In present their first production on Thurs- ed last Tuesday afternoon on the Var- this week, left Washington Thursday eight relay races at the classic. The com- day, May 4th, in Gonzaga College sity Field, where the unit was given the night at 7 p. m. for Quakertown. The petition will be the keenest the country first part of its three-day inspection. hall when Shakespeare's "Julius Caesar" squad which is the largest to represent can offer in the collegiate world, but will be given. The performance will be The General Staff Committee, appoint- repeated on the next evening at 8 o'clock. -

Statistical Leaders of the ‘20S

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 14, No. 2 (1992) Statistical Leaders of the ‘20s By Bob GIll Probably the most ambitious undertaking in football research was David Neft’s effort to re-create statistics from contemporary newspaper accounts for 1920-31, the years before the NFL started to keep its own records. Though in a sense the attempt had to fail, since complete and official stats are impossible, the results of his tireless work provide the best picture yet of the NFL’s formative years. Since the stats Neft obtained are far from complete, except for scoring records, he refrained from printing yearly leaders for 1920-31. But it seems a shame not to have such a list, incomplete though it may be. Of course, it’s tough to pinpoint a single leader each year; so what follows is my tabulation of the top five, or thereabouts, in passing, rushing and receiving for each season, based on the best information available – the stats printed in Pro Football: The Early Years and Neft’s new hardback edition, The Football Encyclopedia. These stats can be misleading, because one man’s yardage total will be based on, say, five complete games and four incomplete, while another’s might cover just 10 incomplete games (i.e., games for which no play-by-play accounts were found). And then some teams, like Rock Island, Green Bay, Pottsville and Staten Island, often have complete stats, based on play-by-plays for every game of a season. I’ll try to mention variations like that in discussing each year’s leaders – for one thing, “complete” totals will be printed in boldface. -

1920 Akron Pros Ken Crippen

Building a Champion: 1920 Akron Pros Ken Crippen BUILDING A CHAMPION: 1920 AKRON PROS By Ken Crippen It’s time to dig deep into the archives to talk about the first National Football League (NFL) champion. In fact, the 1920 Akron Pros were champions before the NFL was called the NFL. In 1920, the American Professional Football Association was formed and started play. Currently, fourteen teams are included in the league standings, but it is unclear as to how many were official members of the Association. Different from today’s game, the champion was not determined on the field, but during a vote at a league meeting. Championship games did not start until 1932. Also, there were no set schedules. Teams could extend their season in order to try and gain wins to influence voting the following spring. These late-season games were usually against lesser opponents in order to pad their win totals. To discuss the Akron Pros, we must first travel back to the century’s first decade. Starting in 1908 as the semi-pro Akron Indians, the team immediately took the city championship and stayed as consistently one of the best teams in the area. In 1912, “Peggy” Parratt was brought in to coach the team. George Watson “Peggy” Parratt was a three-time All-Ohio football player for Case Western University. While in college, he played professionally for the 1905 Shelby Blues under the name “Jimmy Murphy,” in order to preserve his amateur status. It only lasted a few weeks until local reporters discovered that it was Parratt on the field for the Blues. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

The Last Stand of the DULUTH ESKIMOS Y R a R B I L

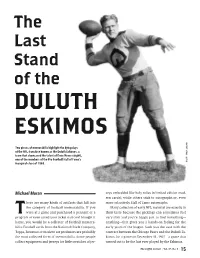

The Last Stand of the DULUTH ESKIMOS Y R A R B I L Two pieces of memorabilia highlight the dying days C I L B of the NFL franchise known as the Duluth Eskimos, a U P H team that showcased the talent of Ernie Nevers (right), T U L U one of the members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s D inaugural class of 1963. Michael Moran seys embedded like holy relics in limited edition mod - ern cards), while others stick to autographs or, even here are many kinds of artifacts that fall into more selectively, Hall of Fame autographs. the category of football memorabilia. If you Many collectors of early NFL material are eclectic in T were at a game and purchased a pennant or a their taste because the pickings can sometimes feel program or even saved your ticket stub and brought it very slim and you’re happy just to find something— home, you would be a collector of football memora - anything—that gives you a hands-on feeling for the bilia. Football cards from the National Chicle Company, early years of the league. Such was the case with the Topps, Bowman or modern set producers are probably contract between the Chicago Bears and the Duluth Es - the most collected form of memorabilia. Some people kimos for a game on December 11, 1927—a game that collect equipment and jerseys (or little swatches of jer - turned out to be the last ever played by the Eskimos. The Coffin Corner | Vol. 37, No. 3 | 15 16 | Vol. -

Afc South Battle Highlights Week 15 Slate

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 12/10/19 http://twitter.com/nfl345 AFC SOUTH BATTLE HIGHLIGHTS WEEK 15 SLATE To help celebrate the NFL’s 100th season, each week will feature an NFL 100 Game of the Week. Each game is a nod to a momentous game played, a fierce rivalry that spans decades, a matchup of original teams and/or a game in which history was made. The NFL has designated the INDIANAPOLIS COLTS-NEW ORLEANS SAINTS matchup as the NFL100 Game of the Week because the contest features the teams from Super Bowl XLIV. On Feb. 7, 2010, in Miami, Fla., the Saints dedicated their 31-17 victory to the New Orleans community, ravaged four years earlier by Hurricane Katrina. Trailing 10-6, Saints head coach SEAN PAYTON surprised everyone by calling for an onside kick to open the second half, and the Saints recovered to set up a go-ahead, 16-yard touchdown pass from DREW BREES to PIERRE THOMAS. The Colts went back on top, 17- 13, with a 4-yard touchdown run by JOSEPH ADDAI, but the Saints shut out Indy’s high-powered offense over the game’s final 21 minutes. Brees guided New Orleans on a nine-play touchdown drive to take a fourth-quarter lead, hitting JEREMY SHOCKEY from 2 yards out, and TRACY PORTER returned an interception 74 yards for a touchdown, the final points in the Saints’ first world championship. AFC SOUTH FIGURES TO GO DOWN TO WIRE: The TENNESSEE TITANS (8-5), who’ve vaulted into the heart of the AFC playoff race with four straight wins, host the HOUSTON TEXANS (8-5) on Sunday (1:00 PM ET, CBS). -

The Rock Island Independents

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 5, No. 3 (1983) THE ROCK ISLAND INDEPENDENTS By Bob Braunwart & Bob Carroll On an October Sunday afternoon in 1921, the Chicago Cardinals held a 7-0 lead after the first quarter at Normal Park on the strength of Paddy Driscoll's 75-year punt return for a touchdown and his subsequent extra point. If there was a downside for the 4,000 assembled Cardinal fans, it was the lackluster performance of the visitors from across state--The Rock Island Independents. But the Independents were not dead. As a matter of fact, their second quarter was to be quite exciting--and certainly one of the most important sessions in the life of their young halfback, Jim Conzelman. It would be nice if we only knew in what order the three crucial events of that second quarter occurred, but newspaper accounts are unclear and personal recollections are vague. Certain it is that the Islanders ruched the ball down the field to the Chicago five. At that point, Quarterback Sid Nichols lofted a short pass to Conzelman in the end zone. After Jim tied the score with a nice kick, the teams lined up to start all over. At the kickoff, Conzelman was down the field like a shot--the Cardinals were to insist he was offsides. Before any Chicagoan could lay hand on the ball, Jim grasped it and zipped unmolested across the goal line. Another kick brought the score to 14-7, as it was to remain through the second half. The third event of that fateful second quarter was the most unusual, but whether it happened before Conzelman's heroics to inspire him or after them to reward him is something we'll probably never know. -

Fighting Illini Football History

HISTORY FIGHTING ILLINI HISTORY ILLINOIS NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP TEAMS 1914 Possibly the most dominant team in Illinois football history was the 1914 squad. The squad was only coach Robert Zuppke’s second at Illinois and would be the first of four national championship teams he would lead in his 29 years at Illinois. The Fighting Illini defense shut out four of its seven opponents, yielding only 22 points the entire 1914 season, and the averaged up an incredible 32 points per game, in cluding a 51-0 shellacking of Indiana on Oct. 10. This team was so good that no one scored a point against them until Oct. 31, the fifth game of the seven-game season. The closest game of the year, two weeks later, wasn’t very close at all, a 21-7 home decision over Chicago. Leading the way for Zuppke’s troops was right halfback Bart Macomber. He led the team in scoring. Left guard Ralph Chapman was named to Walter Camp’s first-team All-America squad, while left halfback Harold Pogue, the team’s second-leading scorer, was named to Camp’s second team. 1919 The 1919 team was the only one of Zuppke’s national cham pi on ship squads to lose a game. Wisconsin managed to de feat the Fighting Illini in Urbana in the third game of the season, 14-10, to tem porarily knock Illinois out of the conference lead. However, Zuppke’s men came back from the Wisconsin defeat with three consecutive wins to set up a showdown with the Buckeyes at Ohio Stadium on Nov. -

HISTORY FIGHTING ILLINI HISTORY ILLINOIS NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP TEAMS 1914 Possibly the Most Dominant Team in Illinois Football History Was the 1914 Squad

HISTORY FIGHTING ILLINI HISTORY ILLINOIS NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP TEAMS 1914 Possibly the most dominant team in Illinois football history was the 1914 squad. The squad was only coach Robert Zuppke’s second at Illinois and would be the first of four national championship teams he would lead in his 29 years at Illinois. The Fighting Illini defense shut out four of its seven opponents, yielding only 22 points the entire 1914 season, and the averaged up an incredible 32 points per game, in cluding a 51-0 shellacking of Indiana on Oct. 10. This team was so good that no one scored a point against them until Oct. 31, the fifth game of the seven-game season. The closest game of the year, two weeks later, wasn’t very close at all, a 21-7 home decision over Chicago. Leading the way for Zuppke’s troops was right halfback Bart Macomber. He led the team in scoring. Left guard Ralph Chapman was named to Walter Camp’s first-team All-America squad, while left halfback Harold Pogue, the team’s second-leading scorer, was named to Camp’s second team. 1919 The 1919 team was the only one of Zuppke’s national cham pi on ship squads to lose a game. Wisconsin managed to de feat the Fighting Illini in Urbana in the third game of the season, 14-10, to tem porarily knock Illinois out of the conference lead. However, Zuppke’s men came back from the Wisconsin defeat with three consecutive wins to set up a showdown with the Buckeyes at Ohio Stadium on Nov. -

108843 FB MG Text 1-110.Indd

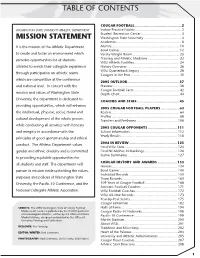

TABLE OF CONTENTS COUGAR FOOTBALL ...........................................2 WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY ATHLETIC DEPARTMENT Indoor Practice Facility ............................................... 2 Student Recreation Center ......................................... 3 MISSION STATEMENT Washington State University ...................................... 4 Academics ................................................................. 8 It is the mission of the Athletic Department Alumni ..................................................................... 10 Bowl Games ............................................................ 12 to create and foster an environment which Varsity Weight Room ................................................ 20 provides opportunities for all student- Training and Athletic Medicine ................................ 22 WSU Athletic Facilities .............................................. 24 athletes to enrich their collegiate experience History Overview ..................................................... 26 WSU Quarterback Legacy ........................................ 28 through participation on athletic teams Cougars in the Pros ................................................. 30 which are competitive at the conference 2005 OUTLOOK ................................................37 and national level. In concert with the Preview .................................................................... 38 Cougar Football Facts .............................................. 42 mission and values of Washington -

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 15, No. 3 (1993)

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 15, No. 3 (1993) IN THE BEGINNING Famous (or forgotten) firsts for every NFL franchise By Tod Maher The following is a comprehensive listing of various first games played by every member, past and present, of the National Football League; its predecessor, the American Professional Football Association; and the American Football League, which merged with the NFL in 1970. Each team's first game ever, first league game, first home league game, first league win and first playoff game are listed. In some cases, one game fills more than one category. A few historical notes are also included. When first ever is in italics, that means it's the earliest known game for that team, but there are earlier games that aren't documented yet. The years of a team's APFA / NFL membership are given in parenthesis, as are the scores of the games involved. AKRON PROS / INDIANS (1920-25 / 26) First ever, Oct. 3, 1920, vs Wheeling Stogies (43-0; first league, home, and win, Oct. 10, 1920, vs Columbus Panhandles (37-0). ATLANTA FALCONS (1966-) First ever, Aug. 1, 1966, vs Philadelphia Eagles (7-9); first league, home, Sept. 11, 1966, vs Los Angeles Rams (14-19); first win, Nov. 20, 1966, at New York Giants (27-16); first playoff, Dec. 24, 1978, vs Philadelphia Eagles (14-13). BALTIMORE COLTS (1950) The Colts were members of the rival All-America Football Conference, 1947-49. First ever, Aug. 22, 1947, vs Buffalo Bisons at Hershey, Pa. (29-20); first league, home, Sept. 17, 1950, vs Washington Redskins (14-38); first win, Nov.