The Racine Legion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nagurski's Debut and Rockne's Lesson

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 20, No. 3 (1998) NAGURSKI’S DEBUT AND ROCKNE’S LESSON Pro Football in 1930 By Bob Carroll For years it was said that George Halas and Dutch Sternaman, the Chicago Bears’ co-owners and co- coaches, always took opposite sides in every minor argument at league meetings but presented a united front whenever anything major was on the table. But, by 1929, their bickering had spread from league politics to how their own team was to be directed. The absence of a united front between its leaders split the team. The result was the worst year in the Bears’ short history -- 4-9-2, underscored by a humiliating 40-6 loss to the crosstown Cardinals. A change was necessary. Neither Halas nor Sternaman was willing to let the other take charge, and so, in the best tradition of Solomon, they resolved their differences by agreeing that neither would coach the team. In effect, they fired themselves, vowing to attend to their front office knitting. A few years later, Sternaman would sell his interest to Halas and leave pro football for good. Halas would go on and on. Halas and Sternaman chose Ralph Jones, the head man at Lake Forest (IL) Academy, as the Bears’ new coach. Jones had faith in the T-formation, the attack mode the Bears had used since they began as the Decatur Staleys. While other pro teams lined up in more modern formations like the single wing, double wing, or Notre Dame box, the Bears under Jones continued to use their basic T. -

1920 Akron Pros Ken Crippen

Building a Champion: 1920 Akron Pros Ken Crippen BUILDING A CHAMPION: 1920 AKRON PROS By Ken Crippen It’s time to dig deep into the archives to talk about the first National Football League (NFL) champion. In fact, the 1920 Akron Pros were champions before the NFL was called the NFL. In 1920, the American Professional Football Association was formed and started play. Currently, fourteen teams are included in the league standings, but it is unclear as to how many were official members of the Association. Different from today’s game, the champion was not determined on the field, but during a vote at a league meeting. Championship games did not start until 1932. Also, there were no set schedules. Teams could extend their season in order to try and gain wins to influence voting the following spring. These late-season games were usually against lesser opponents in order to pad their win totals. To discuss the Akron Pros, we must first travel back to the century’s first decade. Starting in 1908 as the semi-pro Akron Indians, the team immediately took the city championship and stayed as consistently one of the best teams in the area. In 1912, “Peggy” Parratt was brought in to coach the team. George Watson “Peggy” Parratt was a three-time All-Ohio football player for Case Western University. While in college, he played professionally for the 1905 Shelby Blues under the name “Jimmy Murphy,” in order to preserve his amateur status. It only lasted a few weeks until local reporters discovered that it was Parratt on the field for the Blues. -

NFL 1926 in Theory & Practice

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 24, No. 3 (2002) One division, no playoffs, no championship game. Was there ANY organization to pro football before 1933? Forget the official history for a moment, put on your leather thinking cap, and consider the possibilities of NFL 1926 in Theory and Practice By Mark L. Ford 1926 and 2001 The year 1926 makes an interesting study. For one thing, it was 75 years earlier than the just completed season. More importantly, 1926, like 2001, saw thirty-one pro football teams in competition. The NFL had a record 22 clubs, and Red Grange’s manager had organized the new 9 team American Football League. Besides the Chicago Bears, Green Bay Packers and New York Giants, and the Cardinals (who would not move from Chicago until 1959), there were other team names that would be familiar today – Buccaneers (Los Angeles), Lions (Brooklyn), Cowboys (Kansas City) and Panthers (Detroit). The AFL created rivals in major cities, with American League Yankees to match the National League Giants, a pre-NBA Chicago Bulls to match the Bears, Philadelphia Quakers against the Philly-suburb Frankford Yellowjackets, a Brooklyn rival formed around the two of the Four Horsemen turned pro, and another “Los Angeles” team. The official summary of 1926 might look chaotic and unorganized – 22 teams grouped in one division in a hodgepodge of large cities and small towns, and is summarized as “Frankford, Chicago Bears, Pottsville, Kansas City, Green Bay, Los Angeles, New York, Duluth, Buffalo, Chicago Cardinals, Providence, Detroit, Hartford, Brooklyn, Milwaukee, Akron, Dayton, Racine, Columbus, Canton, Hammond, Louisville”. -

Five Modern-Era Players Elected to Pro Football Hall of Fame Selection Committee Selects Five Players Who Join 15-Person Centennial Slate for Special Class of 2020

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 02/01/2020 FIVE MODERN-ERA PLAYERS ELECTED TO PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME SELECTION COMMITTEE SELECTS FIVE PLAYERS WHO JOIN 15-PERSON CENTENNIAL SLATE FOR SPECIAL CLASS OF 2020 CANTON, OHIO – “Selection Saturday” resulted in five “Heroes of the Game” earning election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The Hall’s 48-person Selection Committee held its annual meeting today in Miami Beach to elect five Modern-Era Players for the Class of 2020. The special class also includes the Centennial Slate of 15 Hall of Famers who were picked by a special Blue-Ribbon Panel in January. The Modern-Era players for the Class of 2020 were just announced on stage during taping of NFL Honors, a two-hour primetime awards special that will air nationally tonight at 8 p.m. (ET and PT) on FOX. They include safety STEVE ATWATER, wide receiver ISAAC BRUCE, guard STEVE HUTCHINSON, running back EDGERRIN JAMES, and safety TROY POLAMALU. The five newest Hall of Famers were joined on stage by the living members from the Centennial Slate. Today’s annual selection meeting capped a year-round selection process. The newly elected Hall of Famers were chosen from a list of 15 Finalists who had been determined earlier by the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s Selection Committee. Representatives of the accounting firm Ernst & Young tabulated all votes during Saturday’s meeting. STEVE ATWATER HOF Finalist: 3 | Year of Eligibility: 16 Position: Safety Ht: 6-3, Wt: 218 NFL Career: 1989-1998 Denver Broncos, 1999 New York Jets Seasons: 11, Games: 167 College: Arkansas Drafted: 1st Round (20th overall), 1989 Born: Oct. -

The Rock Island Independents

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 5, No. 3 (1983) THE ROCK ISLAND INDEPENDENTS By Bob Braunwart & Bob Carroll On an October Sunday afternoon in 1921, the Chicago Cardinals held a 7-0 lead after the first quarter at Normal Park on the strength of Paddy Driscoll's 75-year punt return for a touchdown and his subsequent extra point. If there was a downside for the 4,000 assembled Cardinal fans, it was the lackluster performance of the visitors from across state--The Rock Island Independents. But the Independents were not dead. As a matter of fact, their second quarter was to be quite exciting--and certainly one of the most important sessions in the life of their young halfback, Jim Conzelman. It would be nice if we only knew in what order the three crucial events of that second quarter occurred, but newspaper accounts are unclear and personal recollections are vague. Certain it is that the Islanders ruched the ball down the field to the Chicago five. At that point, Quarterback Sid Nichols lofted a short pass to Conzelman in the end zone. After Jim tied the score with a nice kick, the teams lined up to start all over. At the kickoff, Conzelman was down the field like a shot--the Cardinals were to insist he was offsides. Before any Chicagoan could lay hand on the ball, Jim grasped it and zipped unmolested across the goal line. Another kick brought the score to 14-7, as it was to remain through the second half. The third event of that fateful second quarter was the most unusual, but whether it happened before Conzelman's heroics to inspire him or after them to reward him is something we'll probably never know. -

Fighting Illini Football History

HISTORY FIGHTING ILLINI HISTORY ILLINOIS NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP TEAMS 1914 Possibly the most dominant team in Illinois football history was the 1914 squad. The squad was only coach Robert Zuppke’s second at Illinois and would be the first of four national championship teams he would lead in his 29 years at Illinois. The Fighting Illini defense shut out four of its seven opponents, yielding only 22 points the entire 1914 season, and the averaged up an incredible 32 points per game, in cluding a 51-0 shellacking of Indiana on Oct. 10. This team was so good that no one scored a point against them until Oct. 31, the fifth game of the seven-game season. The closest game of the year, two weeks later, wasn’t very close at all, a 21-7 home decision over Chicago. Leading the way for Zuppke’s troops was right halfback Bart Macomber. He led the team in scoring. Left guard Ralph Chapman was named to Walter Camp’s first-team All-America squad, while left halfback Harold Pogue, the team’s second-leading scorer, was named to Camp’s second team. 1919 The 1919 team was the only one of Zuppke’s national cham pi on ship squads to lose a game. Wisconsin managed to de feat the Fighting Illini in Urbana in the third game of the season, 14-10, to tem porarily knock Illinois out of the conference lead. However, Zuppke’s men came back from the Wisconsin defeat with three consecutive wins to set up a showdown with the Buckeyes at Ohio Stadium on Nov. -

HISTORY FIGHTING ILLINI HISTORY ILLINOIS NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP TEAMS 1914 Possibly the Most Dominant Team in Illinois Football History Was the 1914 Squad

HISTORY FIGHTING ILLINI HISTORY ILLINOIS NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP TEAMS 1914 Possibly the most dominant team in Illinois football history was the 1914 squad. The squad was only coach Robert Zuppke’s second at Illinois and would be the first of four national championship teams he would lead in his 29 years at Illinois. The Fighting Illini defense shut out four of its seven opponents, yielding only 22 points the entire 1914 season, and the averaged up an incredible 32 points per game, in cluding a 51-0 shellacking of Indiana on Oct. 10. This team was so good that no one scored a point against them until Oct. 31, the fifth game of the seven-game season. The closest game of the year, two weeks later, wasn’t very close at all, a 21-7 home decision over Chicago. Leading the way for Zuppke’s troops was right halfback Bart Macomber. He led the team in scoring. Left guard Ralph Chapman was named to Walter Camp’s first-team All-America squad, while left halfback Harold Pogue, the team’s second-leading scorer, was named to Camp’s second team. 1919 The 1919 team was the only one of Zuppke’s national cham pi on ship squads to lose a game. Wisconsin managed to de feat the Fighting Illini in Urbana in the third game of the season, 14-10, to tem porarily knock Illinois out of the conference lead. However, Zuppke’s men came back from the Wisconsin defeat with three consecutive wins to set up a showdown with the Buckeyes at Ohio Stadium on Nov. -

Wisarch News 18(2)

WisArch News FALL 2018 Volume 18 Number 2 WisArch News The Newsletter of the Wisconsin Archeological Society Late Woodland Community Plan: A View from the Air In this Issue WAS Officers, Affiliates, Chairs...........2 A Message from the President.…….…3 Affiliated Organizations……………....4 The Fall Society Meeting………........5-7 Aerial Perspective……………….…..8-9 Regional Research……………......10-12 Archaeology News and Notes........13-15 Back Dirt: 100 Years Ago in The Wisconsin Archeologist………...16 WisArch Digital Backissues..…… ......17 Merchandise and Contributing to the Newsletter…………..………….18 Membership in the Wisconsin Archeological Society………......…….19 Aerial View of the Statz Site, Dane County, Wisconsin. Highlights of the Aerial Perspective Digging Fall Society on a Late Woodland Dugouts..……...11 Meeting…….....5-7 Community......8-9 WISARCH NEWS VOLUME 18 NUMBER 2 Wisconsin Archeological Society www.wiarcheologicalsociety.org5TU UU5T5T 2018 Officers, At-Large Directors, Affiliated Organizations & Committee Chairs Elected Officers PresidentU :U Seth A. Schneider, [email protected] (term 2016-2018) PresidentU Elect:UU Rob Nurre, v5TU5TU [email protected] UU5T5T (term 2016-18) SecretaryU :U Katherine M. Sterner, [email protected] UU5T5T (term 2016-2019) TreasurerU :U Jake Rieb, [email protected] UU5T5T (term 2016-2019) Directors at Large George Christiansen (2016-2018), [email protected] Kurt Sampson (2016-2018), [email protected] UU5T5T -

108843 FB MG Text 1-110.Indd

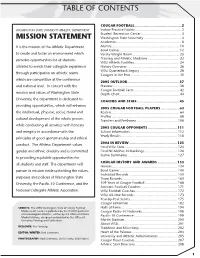

TABLE OF CONTENTS COUGAR FOOTBALL ...........................................2 WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY ATHLETIC DEPARTMENT Indoor Practice Facility ............................................... 2 Student Recreation Center ......................................... 3 MISSION STATEMENT Washington State University ...................................... 4 Academics ................................................................. 8 It is the mission of the Athletic Department Alumni ..................................................................... 10 Bowl Games ............................................................ 12 to create and foster an environment which Varsity Weight Room ................................................ 20 provides opportunities for all student- Training and Athletic Medicine ................................ 22 WSU Athletic Facilities .............................................. 24 athletes to enrich their collegiate experience History Overview ..................................................... 26 WSU Quarterback Legacy ........................................ 28 through participation on athletic teams Cougars in the Pros ................................................. 30 which are competitive at the conference 2005 OUTLOOK ................................................37 and national level. In concert with the Preview .................................................................... 38 Cougar Football Facts .............................................. 42 mission and values of Washington -

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 15, No. 3 (1993)

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 15, No. 3 (1993) IN THE BEGINNING Famous (or forgotten) firsts for every NFL franchise By Tod Maher The following is a comprehensive listing of various first games played by every member, past and present, of the National Football League; its predecessor, the American Professional Football Association; and the American Football League, which merged with the NFL in 1970. Each team's first game ever, first league game, first home league game, first league win and first playoff game are listed. In some cases, one game fills more than one category. A few historical notes are also included. When first ever is in italics, that means it's the earliest known game for that team, but there are earlier games that aren't documented yet. The years of a team's APFA / NFL membership are given in parenthesis, as are the scores of the games involved. AKRON PROS / INDIANS (1920-25 / 26) First ever, Oct. 3, 1920, vs Wheeling Stogies (43-0; first league, home, and win, Oct. 10, 1920, vs Columbus Panhandles (37-0). ATLANTA FALCONS (1966-) First ever, Aug. 1, 1966, vs Philadelphia Eagles (7-9); first league, home, Sept. 11, 1966, vs Los Angeles Rams (14-19); first win, Nov. 20, 1966, at New York Giants (27-16); first playoff, Dec. 24, 1978, vs Philadelphia Eagles (14-13). BALTIMORE COLTS (1950) The Colts were members of the rival All-America Football Conference, 1947-49. First ever, Aug. 22, 1947, vs Buffalo Bisons at Hershey, Pa. (29-20); first league, home, Sept. 17, 1950, vs Washington Redskins (14-38); first win, Nov. -

373 399 Past Standings.Qxd:Past Standings.Qxd

PAST STANDINGS 2011 2010 AMERICAN CONFERENCE NATIONAL CONFERENCE AMERICAN CONFERENCE NATIONAL CONFERENCE East Division East Division East Division East Division W L T Pct. Pts. OP W L T Pct. Pts. OP W L T Pct. Pts. OP W L T Pct. Pts. OP New England# 13 3 0 .813 513 342 New York Giants 9 7 0 .563 394 400 New England# 14 2 0 .875 518 313 Philadelphia 10 6 0 .625 439 377 New York Jets 8 8 0 .500 377 363 Philadelphia 8 8 0 .500 396 328 New York Jets* 11 5 0 .688 367 304 New York Giants 10 6 0 .625 394 347 Miami 6 10 0 .375 329 313 Dallas 8 8 0 .500 369 347 Miami 7 9 0 .438 273 333 Dallas 6 10 0 .375 394 436 Buffalo 6 10 0 .375 372 434 Washington 5 11 0 .313 288 367 Buffalo 4 12 0 .250 283 425 Washington 6 10 0 .375 302 377 North Division North Division North Division North Division W L T Pct. Pts. OP W L T Pct. Pts. OP W L T Pct. Pts. OP W L T Pct. Pts. OP Baltimore 12 4 0 .750 378 266 Green Bay# 15 1 0 .938 560 359 Pittsburgh 12 4 0 .750 375 232 Chicago 11 5 0 .688 334 286 Pittsburgh* 12 4 0 .750 325 227 Detroit* 10 6 0 .625 474 387 Baltimore* 12 4 0 .750 357 270 Green Bay* 10 6 0 .625 388 240 Cincinnati* 9 7 0 .563 344 323 Chicago 8 8 0 .500 353 341 Cleveland 5 11 0 .313 271 332 Detroit 6 10 0 .375 362 369 Cleveland 4 12 0 .250 218 307 Minnesota 3 13 0 .188 340 449 Cincinnati 4 12 0 .250 322 395 Minnesota 6 10 0 .375 281 348 South Division South Division South Division South Division W L T Pct. -

The Pioneers

Gridiron Glory: Footballs Greatest Legends and Moments is the most extensive and comprehensive exhibit featuring America’smost popular sport ever to tour. Many of the objects included in the exhibition have never been outside the walls of their home, the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The artifacts are representative of the great moments, great players and coaches and milestone moments of the sport over the last 100-plus years. Below is a partial list of the rare and historically significant artifacts that will be presented in Gridiron Glory: Footballs Greatest Legends and Moments. The Pioneers This section looks at the early days of the sport when a very unorganized, rough and tumble game was played in empty lots and other makeshift venues. It captures the moment when the NFL was born, when the rules of the game were created anew on every field and when one player of staggering ability, Red Grange, “barnstormed” across America to drum up fan support for a sport in its infancy. Artifacts featured include: 1892 Allegany Athletic Association accounting ledger – Pro Football’sBirth Certificate This accounting ledger sheet from the 1892 Allegheny Athletic Association documents football’s first case of professionalism. “Pro Football’sBirth Certificate” has never before been displayed outside the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Jim Thorpe’sCanton bulldogs Sideline Blanket In 1915 the Canton Bulldogs signed Jim Thorpe to a $250 per game contract. Thorpe, the first big-name athlete to play pro football, was an exceptional talent and major gate attraction. His outstanding talent enabled Canton to lay claim to unofficial world championships in 1916, 1917 and 1919.