Comparative Genomic Analyses Illuminate the Distinct Evolution Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Predicted the Impacts of Climate Change and Extreme-Weather Events on the Future

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.13.443960; this version posted May 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Predicted the impacts of climate change and extreme-weather events on the future distribution of fruit bats in Australia Vishesh L. Diengdoh1, e: [email protected], ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000- 0002-0797-9261 Stefania Ondei1 - e: [email protected] Mark Hunt1, 3 - e: [email protected] Barry W. Brook1, 2 - e: [email protected] 1School of Natural Sciences, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart TAS 7005 Australia 2ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Australia 3National Centre for Future Forest Industries, Australia Corresponding Author: Vishesh L. Diengdoh Acknowledgements We thank John Clarke and Vanessa Round from Climate Change in Australia (https://www.climatechangeinaustralia.gov.au/)/ Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) for providing the data on extreme weather events. This work was supported by the Australian Research Council [grant number FL160100101]. Conflict of Interest None. Author Contributions bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.13.443960; this version posted May 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. -

The World at the Time of Messel: Conference Volume

T. Lehmann & S.F.K. Schaal (eds) The World at the Time of Messel - Conference Volume Time at the The World The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 2011 Frankfurt am Main, 15th - 19th November 2011 ISBN 978-3-929907-86-5 Conference Volume SENCKENBERG Gesellschaft für Naturforschung THOMAS LEHMANN & STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL (eds) The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference Frankfurt am Main, 15th – 19th November 2011 Conference Volume Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung IMPRINT The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main, Germany Conference Volume Publisher PROF. DR. DR. H.C. VOLKER MOSBRUGGER Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany Editors DR. THOMAS LEHMANN & DR. STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected]; [email protected] Language editors JOSEPH E.B. HOGAN & DR. KRISTER T. SMITH Layout JULIANE EBERHARDT & ANIKA VOGEL Cover Illustration EVELINE JUNQUEIRA Print Rhein-Main-Geschäftsdrucke, Hofheim-Wallau, Germany Citation LEHMANN, T. & SCHAAL, S.F.K. (eds) (2011). The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates. 22nd International Senckenberg Conference. 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main. Conference Volume. Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, Frankfurt am Main. pp. 203. -

Cynopterus Minutus, Minute Fruit Bat

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2019: T136423A21985433 Scope: Global Language: English Cynopterus minutus, Minute Fruit Bat Assessment by: Ruedas, L. & Suyanto, A. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Ruedas, L. & Suyanto, A. 2019. Cynopterus minutus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T136423A21985433. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019- 3.RLTS.T136423A21985433.en Copyright: © 2019 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: Arizona State University; BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Mammalia Chiroptera Pteropodidae Taxon Name: Cynopterus minutus Miller, 1906 Common Name(s): • English: Minute Fruit Bat Taxonomic Notes: This may be a species complex. -

Four Species in One: Multigene Analyses Reveal Phylogenetic

Published by Associazione Teriologica Italiana Volume 29 (1): 111–121, 2018 Hystrix, the Italian Journal of Mammalogy Available online at: http://www.italian-journal-of-mammalogy.it doi:10.4404/hystrix–00017-2017 Research Article Four species in one: multigene analyses reveal phylogenetic patterns within Hardwicke’s woolly bat, Kerivoula hardwickii-complex (Chiroptera, Vespertilionidae) in Asia Vuong Tan Tu1,2,3,4,∗, Alexandre Hassanin1,2,∗, Neil M. Furey5, Nguyen Truong Son3,4, Gábor Csorba6 1Institut de Systématique, Evolution, Biodiversité (ISYEB), UMR 7205 MNHN CNRS UPMC, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Case postale N°51–55, rue Buffon, 75005 Paris, France 2Service de Systématique Moléculaire, UMS 2700, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Case postale N°26–43, rue Cuvier, 75005 Paris, France 3Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, 18 Hoang Quoc Viet road, Cau Giay district, Hanoi, Vietnam 4Graduate University of Science and Technology, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, 18 Hoang Quoc Viet road, Cau Giay district, Hanoi, Vietnam 5Fauna & Flora International, Cambodia Programme, 19 Street 360, Boeng Keng Kang 1, Chamkarmorn, Phnom Penh, Cambodia 6Department of Zoology, Hungarian Natural History Museum, Baross u. 13., H-1088, Budapest, Hungary Keywords: Abstract Kerivoulinae Asia We undertook a comparative phylogeographic study using molecular, morphological and morpho- phylogeography metric approaches to address systematic issues in bats of the Kerivoula hardwickii complex in Asia. taxonomy Our phylogenetic reconstructions using DNA sequences of two mitochondrial and seven nuclear cryptic species genes reveal a distinct clade containing four small-sized species (K. hardwickii sensu stricto, K. depressa, K. furva and Kerivoula sp. -

Bat Distribution Size Or Shape As Determinant of Viral Richness in African Bats

Bat Distribution Size or Shape as Determinant of Viral Richness in African Bats Gae¨l D. Maganga1,2., Mathieu Bourgarel1,3,4*., Peter Vallo5,6, Thierno D. Dallo7, Carine Ngoagouni8, Jan Felix Drexler7, Christian Drosten7, Emmanuel R. Nakoune´ 8, Eric M. Leroy1,9, Serge Morand3,10,11. 1 Centre International de Recherches Me´dicales de Franceville, Franceville, Gabon, 2 Institut National Supe´rieur d’Agronomie et de Biotechnologies (INSAB), Franceville, Gabon, 3 CIRAD, UPR AGIRs, Montpellier, France, 4 CIRAD, UPR AGIRs, Harare, Zimbabwe, 5 Institute of Vertebrate Biology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Brno, Czech Republic, 6 Institute of Experimental Ecology, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany, 7 Institute of Virology, University of Bonn Medical Centre, Bonn, Germany, 8 Institut Pasteur de Bangui, Bangui, Re´publique Centrafricaine, 9 Institut de Recherche pour le De´veloppement, UMR 224 (MIVEGEC), IRD/CNRS/UM1, Montpellier, France, 10 Institut des Sciences de l’Evolution, CNRS-UM2, CC065, Universite´ de Montpellier 2, Montpellier, France, 11 Centre d’Infectiologie Christophe Me´rieux du Laos, Vientiane, Lao PDR Abstract The rising incidence of emerging infectious diseases (EID) is mostly linked to biodiversity loss, changes in habitat use and increasing habitat fragmentation. Bats are linked to a growing number of EID but few studies have explored the factors of viral richness in bats. These may have implications for role of bats as potential reservoirs. We investigated the determinants of viral richness in 15 species of African bats (8 Pteropodidae and 7 microchiroptera) in Central and West Africa for which we provide new information on virus infection and bat phylogeny. -

Inferring Echolocation in Ancient Bats Arising From: N

NATURE | Vol 466 | 19 August 2010 BRIEF COMMUNICATIONS ARISING Inferring echolocation in ancient bats Arising from: N. Veselka et al. Nature 463, 939–942 (2010) Laryngeal echolocation, used by most living bats to form images of O. finneyi falls outside the size range seen in living echolocating bats their surroundings and to detect and capture flying prey1,2, is con- and is similar to the proportionally smaller cochleae of bats that lack sidered to be a key innovation for the evolutionary success of bats2,3, laryngeal echolocation4,8, suggesting that it did not echolocate. and palaeontologists have long sought osteological correlates of echolocation that can be used to infer the behaviour of fossil bats4–7. Veselka et al.8 argued that the most reliable trait indicating echoloca- tion capabilities in bats is an articulation between the stylohyal bone (part of the hyoid apparatus that supports the throat and larynx) and a the tympanic bone, which forms the floor of the middle ear. They examined the oldest and most primitive known bat, Onychonycteris finneyi (early Eocene, USA4), and argued that it showed evidence of this stylohyal–tympanic articulation, from which they concluded that O. finneyi may have been capable of echolocation. We disagree with their interpretation of key fossil data and instead argue that O. finneyi was probably not an echolocating bat. The holotype of O. finneyi shows the cranial end of the left stylohyal resting on the tympanic bone (Fig. 1c–e). However, the stylohyal on the right side is in a different position, the tip of the stylohyal extends beyond the tympanic on both sides of the skull, and both tympanics are crushed. -

A Recent Bat Survey Reveals Bukit Barisan Selatan Landscape As A

A Recent Bat Survey Reveals Bukit Barisan Selatan Landscape as a Chiropteran Diversity Hotspot in Sumatra Author(s): Joe Chun-Chia Huang, Elly Lestari Jazdzyk, Meyner Nusalawo, Ibnu Maryanto, Maharadatunkamsi, Sigit Wiantoro, and Tigga Kingston Source: Acta Chiropterologica, 16(2):413-449. Published By: Museum and Institute of Zoology, Polish Academy of Sciences DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3161/150811014X687369 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3161/150811014X687369 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Acta Chiropterologica, 16(2): 413–449, 2014 PL ISSN 1508-1109 © Museum and Institute of Zoology PAS doi: 10.3161/150811014X687369 A recent -

Mammals of Jordan

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mammals of Jordan Z. AMR, M. ABU BAKER & L. RIFAI Abstract: A total of 78 species of mammals belonging to seven orders (Insectivora, Chiroptera, Carni- vora, Hyracoidea, Artiodactyla, Lagomorpha and Rodentia) have been recorded from Jordan. Bats and rodents represent the highest diversity of recorded species. Notes on systematics and ecology for the re- corded species were given. Key words: Mammals, Jordan, ecology, systematics, zoogeography, arid environment. Introduction In this account we list the surviving mammals of Jordan, including some reintro- The mammalian diversity of Jordan is duced species. remarkable considering its location at the meeting point of three different faunal ele- Table 1: Summary to the mammalian taxa occurring ments; the African, Oriental and Palaearc- in Jordan tic. This diversity is a combination of these Order No. of Families No. of Species elements in addition to the occurrence of Insectivora 2 5 few endemic forms. Jordan's location result- Chiroptera 8 24 ed in a huge faunal diversity compared to Carnivora 5 16 the surrounding countries. It shelters a huge Hyracoidea >1 1 assembly of mammals of different zoogeo- Artiodactyla 2 5 graphical affinities. Most remarkably, Jordan Lagomorpha 1 1 represents biogeographic boundaries for the Rodentia 7 26 extreme distribution limit of several African Total 26 78 (e.g. Procavia capensis and Rousettus aegypti- acus) and Palaearctic mammals (e. g. Eri- Order Insectivora naceus concolor, Sciurus anomalus, Apodemus Order Insectivora contains the most mystacinus, Lutra lutra and Meles meles). primitive placental mammals. A pointed snout and a small brain case characterises Our knowledge on the diversity and members of this order. -

Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)

Chapter 6 Phylogenetic Relationships of Harpyionycterine Megabats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) NORBERTO P. GIANNINI1,2, FRANCISCA CUNHA ALMEIDA1,3, AND NANCY B. SIMMONS1 ABSTRACT After almost 70 years of stability following publication of Andersen’s (1912) monograph on the group, the systematics of megachiropteran bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) was thrown into flux with the advent of molecular phylogenetics in the 1980s—a state where it has remained ever since. One particularly problematic group has been the Austromalayan Harpyionycterinae, currently thought to include Dobsonia and Harpyionycteris, and probably also Aproteles.Inthis contribution we revisit the systematics of harpyionycterines. We examine historical hypotheses of relationships including the suggestion by O. Thomas (1896) that the rousettine Boneia bidens may be related to Harpyionycteris, and report the results of a series of phylogenetic analyses based on new as well as previously published sequence data from the genes RAG1, RAG2, vWF, c-mos, cytb, 12S, tVal, 16S,andND2. Despite a striking lack of morphological synapomorphies, results of our combined analyses indicate that Boneia groups with Aproteles, Dobsonia, and Harpyionycteris in a well-supported, expanded Harpyionycterinae. While monophyly of this group is well supported, topological changes within this clade across analyses of different data partitions indicate conflicting phylogenetic signals in the mitochondrial partition. The position of the harpyionycterine clade within the megachiropteran tree remains somewhat uncertain. Nevertheless, biogeographic patterns (vicariance-dispersal events) within Harpyionycterinae appear clear and can be directly linked to major biogeographic boundaries of the Austromalayan region. The new phylogeny of Harpionycterinae also provides a new framework for interpreting aspects of dental evolution in pteropodids (e.g., reduction in the incisor dentition) and allows prediction of roosting habits for Harpyionycteris, whose habits are unknown. -

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

2020 Special Issue

Journal Home page : www.jeb.co.in « E-mail : [email protected] Original Research Journal of Environmental Biology TM p-ISSN: 0254-8704 e-ISSN: 2394-0379 JEB CODEN: JEBIDP DOI : http://doi.org/10.22438/jeb/4(SI)/MS_1904 Plagiarism Detector Grammarly New records and present status of bat fauna in Mizoram, North-Eastern India C. Vanlalnghaka Department of Zoology, Govt. Serchhip College, Mizoram–796 181, India *Corresponding Author Email : [email protected] Paper received: 08.12.2019 Revised received: 24.06.2020 Accepted: 10.07.2020 Abstract Aim: The present study aimed to investigate the diversity of bat fauna in Mizoram and prepare a checklist for future references. This study also investigated threats and suggested recommendations for implementing conservation measures for bat fauna in Mizoram. Methodology: The present study was carried out in different parts of Mizoram between January 2012 - October 2019. Bats were trapped by using mist nets and hoop nets. Diagnostic morphological characters of bat were used for species identification. Digital camera and video camera were also used for further identification and documentation of bats. Results: During January 2012 – December 2016, eighteen bat species were identified. Recently, from January 2017 - October 2019 insectivorous bat species, Scotomanes ornatus was first time documented in Serchhip District (23.3 ºN 92.83 ºE), Mizoram. In total nineteen bat species were identified in this study, out of which ten species were first time recorded and nine species were rediscovered from the previous documentation. From the previous and present data, total of thirty-six bat Study the diversity of bat fauna and prepared checklist in species were recorded in Mizoram- nine Mizoram. -

Inferring the Ecological Niche of Bat Viruses Closely Related to SARS-Cov-2 Using Phylogeographic Analyses of Rhinolophus Specie

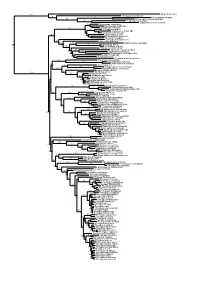

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Inferring the ecological niche of bat viruses closely related to SARS‑CoV‑2 using phylogeographic analyses of Rhinolophus species Alexandre Hassanin1,4*, Vuong Tan Tu2,4, Manon Curaudeau1 & Gabor Csorba3 The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) is the causal agent of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) pandemic. To date, viruses closely related to SARS‑CoV‑2 have been reported in four bat species: Rhinolophus acuminatus, Rhinolophus afnis, Rhinolophus malayanus, and Rhinolophus shameli. Here, we analysed 343 sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene (CO1) from georeferenced bats of the four Rhinolophus species identifed as reservoirs of viruses closely related to SARS‑CoV‑2. Haplotype networks were constructed in order to investigate patterns of genetic diversity among bat populations of Southeast Asia and China. No strong geographic structure was found for the four Rhinolophus species, suggesting high dispersal capacity. The ecological niche of bat viruses closely related to SARS‑CoV‑2 was predicted using the four localities in which bat viruses were recently discovered and the localities where bats showed the same CO1 haplotypes than virus‑positive bats. The ecological niche of bat viruses related to SARS‑CoV was deduced from the localities where bat viruses were previously detected. The results show that the ecological niche of bat viruses related to SARS‑CoV2 includes several regions of mainland Southeast Asia whereas the ecological niche of bat viruses related to SARS‑CoV is mainly restricted to China. In agreement with these results, human populations in Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand appear to be much less afected by the COVID‑19 pandemic than other countries of Southeast Asia.