Faith for an Ideological Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Anonymous Groups

The Enduring Legacy: the anonymous groups The apology that launched a million amends By Jay Stinnett, Los Angeles July 27th, 2008, marked the 100th anniversary of Frank Buchman’s Spiritual Awakening – one that directly linked him to the cofounders of AA. As a young man Buchman gave everything he had to establishing a shelter for homeless boys in the slums of Philadelphia. The shelters success surpassed his budget and the six-member board of directors insisted that he cut the amount of food being given to his charges. He quit instead of cutting back. Resentment consumed him. His family despaired that he might not come to his senses. His work was destroyed by what he saw as the short-sightedness of others. His health was well past the breaking point. “Everywhere I went, I took me with me,” he later said. During a trip to recuperate in Europe, he exhausted the funds his father gave him and existed on the kindness of his family and the generosity of acquaintances. Tired and dejected he went to an Evangelical Conference in Keswick, England, hoping to connect with F.B. Meyer, a famous minister he knew, for spiritual help. Meyer was not in attendance; another plan gone awry. July 27, 1908, thirty year-old Frank Buchman, a Pennsylvanian Lutheran Minister, walked into an afternoon service with 17 other people to hear Jessie Penn Lewis preach on the cross of Christ. And then it happened. As Buchman sat in that Chapel, “There was a moment of spiritual peak of what God could do for me. -

View of the Essentials of Group Cohesion

ABSTRACT THE SPIRITUAL DYNAMIC IN ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS AND THE FACTORS PRECIPITATING A.A.’S SEPARATION FROM THE OXFORD GROUP by Andrew D. Feldheim Alcoholics Anonymous has grown since the mid-1930’s from a loose cohesion of individuals seeking recovery to iconic status as a paradigmatic self-help organization. Few people among the many familiar with A.A. are aware of its genesis from a popular Christian evangelical organization called the Oxford Group. This paper charts the course of A.A. from its Oxford Group roots, both in terms of historical development and the evolution of the spiritual dynamic that served as the functional nexus for both organizations. This paper also addresses key differences in the agendas of both groups that eventually necessitated their separation, as well as the questionable assumption that Alcoholics Anonymous is the more “secular” of the two. THE SPIRITUAL DYNAMIC IN ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS AND THE FACTORS PRECIPITATING A.A.’S SEPARATION FROM THE OXFORD GROUP A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Comparative Religion By Andrew Feldheim Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2013 Advisor ________________ Elizabeth Wilson Reader _________________ Peter Williams Reader ___________________ SCott Kenworthy TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter 1: History of the Oxford Group………………………………………………………3 Chapter 2: The Development of Alcoholics Anonymous……………………………...13 Chapter 3: The Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions……………………………………32 Chapter 4: Response to an Anticipated Objection and Closing Remarks……..45 ii Introduction Most people have heard of Alcoholics Anonymous, as well as many of the “spin offs” from this group, like Narcotics Anonymous and Overeaters Anonymous. -

Dr. Frank Buchman Founder of the Oxford Group Dr

Dr. Frank Buchman Founder of the Oxford Group Dr. Frank Buchman & Conrad Adenauer First page “What Is The Oxford Group” description Assorted Oxford Group books. Oxford Group Book 2 Oxford Group Books: A.J. Russell For Sinners Only and V.C. Kitchen I Was A Pagan Rowland H. (left), wife and son. Rowland carried the Oxford Group message to Ebby. Cebra Graves Ebby was released from court to Rowland H. and Cebra’s care Dr. Carl Jung Carl Jung’s Modern Man in Search of a Soul William James Father of American Psychiatry William James Book Varieties of Religious Experience Ebby carried this book to Bill at Townes Hospital The Common Sense of Drinking by Richard Peabody Once an alcoholic, always an alcoholic Half measures availed us nothing 1932 Akron newspaper article on the Oxford Group. Frank Buchman is in the picture. Frank Buchman and 60 members of the Oxford Group invited to Akron by Harvey Firestone Reverend Sam Shoemaker With the Calvary Church, and head of the Oxford Group in U.S. Calvary Episcopal Church – 21st Street and Park Avenue South. Headquarters of the Oxford Group. Bill W. went to Oxford meetings before the founding of A.A. Calvary House adjacent to the Calvary Episcopal Church Entrance to the street mission Bill and Ebby Ebby carried “The Message” to Bill Bill and Lois’s house, 182 Clinton Street, Brooklyn A note from Bill to Ebby “Wishes for a Merry Christmas and thanks.” Dr. Leonard Strong – A.A. trustee and brother-in-law of Bill Wilson. Townes Hospital located at Central Park West and 89th Street NYC. -

Paul Tournier's Philosophy of Counseling As Developed from His Concept of Person Laurence H

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Western Evangelical Seminary Theses Western Evangelical Seminary 5-1-1974 Paul Tournier's Philosophy of Counseling as Developed from His Concept of Person Laurence H. Wood PAUL TOURNIER 'S PHILOSOPHY OF COUNSELING AS DEVELOPED FROM HIS CONCEPT OF PERSON A Graduate Research Project Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Western Evangelical Seminary In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Divinity by Laurence H. Wood Jr. May 1974 APPROVED BY Major Professor: •.--t Lei{)~~~ 17::L .4"~p / TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. INTRODUCTION. 1 THE PROBLEM • 1 Statement of the Problem 1 Justification of the Problem 2 Limitation of the Study • 3 Definition of Key Terms • 4 SOURCES OF DATA • 5 STATEMENT OF ORGANIZATION • 5 2. THE LIFE AND WORK OF PAUL TOURNIER 7 Paul Tournier 1 s Parents • 8 The Early Years • 9 The Impersonal Years 10 The Years of Change and Growth 13 Doctor of Medicine of the Whole Person 17 The Productive Years. 21 Retirement Years 26 SUMMARY • 27 3 • THE MEANING OF PERSONS . 29 Personage and Person 29 The Failure of Science 33 Obstacles in the Search • 33 iii iv Chapter Page PROBLEMS IN FINDING THE PERSON 35 Utopia 35 The Example of Biology 37 Psychology and Spirit • 39 FINDING THE PERSON 41 The Dialogue 41 The Obstacle 43 The Living God 45 COMMITMENT TO THE PERSON 47 The World of Things and the World of Persons 47 To Live is to Choose 49 New Life 50 SUMMARY • 51 4 • THE PERSON REBORN 53 TECHNOLOGY AND FAITH 54 Technology or Faith • 55 Psychoanalysis and Soul-healing • 56 The Two Aspects of Man 57 Grace • . -

WAB: the Oxford Group/Moral Re-Armament Records, 1931-1961 2

The Burke Library Archives, Columbia University Libraries, Union Theological Seminary, New York William Adams Brown Ecumenical Archives Group Finding Aid for The Oxford Group/Moral Re-Armament Records, 1931-1961 “You Can Defend America” Songbook WAB: OGMRA Records, Box 4, Folder 3, The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary, Columbia University in the City of New York. Finding Aid prepared by: Sarah Davis and Brigette C. Kamsler, March 2014 With financial support from the Henry Luce Foundation Summary Information Creator: The Oxford Group/Moral Re-Armament/Frank Buchman (1878-1961) Title: The Oxford Group/Moral Re-Armament Records Inclusive dates: 1931-1961 Bulk dates: 1944-1959 Abstract: The Oxford Group was the parent company of Moral Re-Armament (MRA), an organization/movement that sought to defend America and the nation’s freedoms through a resurgence of morality. Collection contains pamphlets, newspaper articles, advertisements, and other materials related to spreading the MRA message. Size: 4 boxes, 1.75 linear feet Storage: Onsite storage Repository: The Burke Library Union Theological Seminary 3041 Broadway New York, NY 10027 Email: [email protected] WAB: The Oxford Group/Moral Re-Armament Records, 1931-1961 2 Administrative Information Provenance: The papers are part of the William Adams Brown Ecumenical Library Collection, which was founded in 1945 by the Union Theological Seminary Board of Directors. Access: Archival papers are available to registered readers for consultation by appointment only. Please contact archives staff by email to [email protected], or by postal mail to The Burke Library address on page 1, as far in advance as possible Burke Library staff is available for inquiries or to request a consultation on archival or special collections research. -

The Meaning of Gifts by Paul Tournier Christmas in Japan and Cameroon

The Meaning of Gifts Christmas in Japan Liberating Christ from Christmas December 1969 by Paul Tournier and Cameroon by Richard John Neuhaus by Lucille Wipf/ Peter Fehr Bop istHerold Volume 47 December 1969 No. 20 The Meaning of Gifts, Paul Tournier, 4 Christmas in Japan, Lucille Wipf, 6 Christmas in Cameroon, Peter Fehr, 7 History of the Baptist Herald, M. L. Leuschner, 8 A Post-Christmas Prayer, Charles Waugaman, 12 Valley View Baptist Plans to Organize and Build, Herbert Vetter, 13 Love is a Feeling, Walter Trobisch, 14 Liberating Christ from Christmas, John Neuhaus, 15 Coming World Peace and Evangelism, Mark H atfield, 18 An Agnostic and Christmas, 21 Baptist Herald Index, January to December 1969, 26 Ask the Professor, Gerald Borchert, 10 God's Volunteers, JO Youth Scene, Bruce Rich, 11 Book Reviews, B. C. Schreiber, 12 We the Women, Mrs. Herbert Hiller, 22 Insight Into Christian Education, edited by Dorothy Pritzkan; Children are Natural Believers, Ervin Gerlitz, 23 Bible Study, James Schacher, 24 Our Churches in Acti on, 28 In Memoriam, 31 News & Views, 32 As I See It, Paul Siewert, 32 What's Happening, 32 Editori al: A New Look, Sharing the Christmas Event, 34 Open Dialogue, 34 Mo111hlv Puhlication of the Editor: Joh n Binder o f the · North A 1ll!·rica11 Baptist Editorial Assis/a/I/: Bruno Schreiber /?ager IVilliwm Press G eneral Conference Business M anager: Eldon Janzen HOPE. 7 308 /\fadisnn Street l:."ditMial Co111 111ittee: John Bi11der the promise of Christmas Forest Park. Illinois 60130 G rrhard Panke. Arthur Garling PEACE . the message of Christmas Gl'rald Borchert. -

Introduction to Person-Centred Medicine: from Concepts

Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice ISSN 1365-2753 From the Second Geneva Conference on Person Centered Medicine Person-Centered Medicine: From Concepts to Practice EDITORIAL Introduction to person-centred medicine: from concepts to practicejep_1606 330..332 Juan E. Mezzich MD PhD,1 Jon Snaedal MD,2 Chris van Weel MD PhD,3 Michel Botbol MD4 and Ihsan Salloum MD MPH5 1President, International Network for Person-centered Medicine, President 2005–2008, World Psychiatric Association and Professor of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York University, New York, USA 2President 2007–2008, World Medical Association and Board Member, International Network for Person-centered Medicine, Department of Geriatrics, Landspitali University Hospital, Reykjavik, Iceland 3President 2007–2010, World Organization of Family Doctors, Board Member, International Network for Person-centered Medicine and Professor of General Practice, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands 4Board Member, International Network for Person-centered Medicine and Associate Professor, School of Psychology, Catholic University, Paris, France 5Board Member, International Network for Person-centered Medicine and Professor of Psychiatry, University of Miami, Miami, Florida, USA Keywords Correspondence person-centred medicine, science and Professor Juan E. Mezzich Accepted for publication: 11 October 2010 humanism in medicine Mount Sinai School of Medicine New York University doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01606.x Fifth Ave and 100th St, Box 1093 New York, NY 10029 USA E-mail: [email protected] The early roots of the concept of person-centred medicine can be the International Council of Nurses (ICN), the European Federa- found in the comprehensive notion of health and the personalized tion of Associations of Families of People with Mental Illness approaches to medical care discernible in both Eastern and (EUFAMI), the International Alliance of Patients’ Organizations Western ancient civilizations [1,2]. -

Current Background Theology

A Synopsis of the Theological Systems Behind Current UK Church Streams How to see the wood for the trees in today’s evangelical mess. Paul Fahy 2 A Synopsis of the Theological Systems Behind Current UK Church Streams Contents Why is this important? Amyraldism Arminianism Calvinism / Reformed Theology Cessationism Charismatic Theology / Neo Pentecostalism Deeper Life / Higher Life / Victorious Life / Keswick Teachings Deliverance Theology Dominionism 1: Reconstructionism / Theonomy Dominionism 2: Charismatic Kingdom Theology Dispensationalism [Dispensational Premillennialism] Ecumenical Theology & Movements The Emerging Church Federal Vision Fullerism Hyper-Calvinism Humanism Jewish Roots Liberal Theology Modernism Mysticism / New Age New (or Neo) Evangelicalism Neo Orthodoxy [Dialectical Theology or The New Hermeneutic] The New Perspective on Paul / Justification / Judaism Oberlin Theology (Finneyism) / New Haven Theology / New Divinity Occult Theology / Paganism Open Theism Pentecostalism Perfectionism Psychoheresy Quietism Sacramentalism Seeker-sensitive Practices / Church Growth Movement Strategic Level Spiritual Warfare Theology / Territorial Spirits Universalism - No hell as future punishment Conclusion 3 Appendixes Appendix One: The Progress of Charismatic Error Appendix Two: The Jewish Roots Reaction to Extreme Charismaticism Appendix Three: The Eschatological Key to Current Charismatic Factions Appendix Four: The Diminishing of the authority of God’s Word Appendix Five: The Impact of the Mind Sciences Appendix Six: The Rise of -

Iofc-Uk-Annual-Report-2013.Pdf

Company No 355987 Registered Charity No 226334 THE OXFORD GROUP OPERATING AS INITIATIVES OF CHANGE ANNUAL REPORT 2013 INCLUDING ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2013 Copies of this and previous Annual Reports and Accounts are available for download at www.uk.iofc.org/annual-report CONTENTS CHAIR’S INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 5 Name and Objects ................................................................................................................................... 6 Public Benefit ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Appointment and induction of Trustees ................................................................................................. 7 Organisation ............................................................................................................................................ 7 Articles of Association ............................................................................................................................. 8 Properties ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Archives ................................................................................................................................................... 8 Risk Assessment and Sustainability ........................................................................................................ -

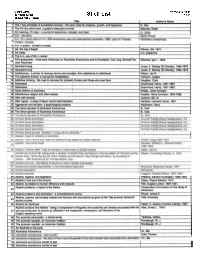

Shelf List 1/18 East Dorset VT 05253 Title Author's Name 1 the 7 Key Principles of Successful Recovery: the Basic Tools for Progress, Growth, and Happiness B., Mel

Griffith Library 07/25/0514:13:40 38 Village Street Shelf List 1/18 East Dorset VT 05253 Title Author's Name 1 The 7 key principles of successful recovery: the basic tools for progress, growth, and happiness B., Mel. 2 The 24 hour drink b~u!de to executive survival. Maloney, Ralph. --- 61 A.A. in prison: inmate to inmate. 71 AA, the way it began I Pittman, Bill, 1947-_1 way of life; a reader 10I AA's godparents: three early influences on Alcoholics Anonymous and its foundation, Carl Jung, Emmet Fox, Sikorsky, Igor I., 1929- I Jack Alexander 11 Abundant living Jones, E. Stanley (Eli Stanley), 1884-1973:l 12 Abundant living Jones, E. Stanley (Eli Stanley), 1884-1973. I 13 Addictionary: a primer of recovery terms and concepts, from abstinence to withdrawal Wilson, Jan R. I 14 The addictive drinker; a manual for rehabilitation. Thimann, Joseph. I 15 Addictive drinking: the road to recovery for problem drinkers and those who love them Vaughan, Clark. I 16 Addresses Drummond, Henry, 1851-1897. 171 Addresses I Drum~o_nd._Henry. 1851-~~97. 181 Adult children of alcohoTi-cs ~ Woititz, Janet Geringer. 191 Adventurous religion and other essays Fosdick, Harry Emerson, 1878-1969. 20 Afire with serenity Jackson, Bill, Dr. 21 After repeal: a study of liquor control administration Harrison, Leonard Vance, 1891- 22 Aggression and altruism, a psychological analysis. Kaufmann, Harry. 23 The Akron genesis of Alcoholics Anonymous B., Dick. 24 The Akron qenesis of Alcoholics Anonymous B. Dick. Alcohol, hygiene, and legislation EdwardHu~ington!~~ 411 Alcohol in and out of the church lOates,_~ayne Edward, 1917- ~IXcohof; Its relation to human efficiency and longevity Fisk, Eugene Lyman, 1867-1931.~ Alcohol problems; a report to the Nation. -

Frank Buchman 1878 – 1961 Founder of the Oxford Group

Frank Buchman 1878 – 1961 Founder of the Oxford Group Franklin Nathaniel Daniel, best known as Dr. or Rev. Frank Buch- "The Oxford Group is a Christian revolution for remaking the man, was a Protestant Christian evangelist who founded the Ox- world. The root problems in the world today are dishonesty, self- ford Group (known as Moral Re-Armament from 1938 until 2001, ishness and fear – in men and, consequently, in nations. These and as Initiatives of Change since then). evils multiplied result in divorce, crime, unemployment, recurrent depression and war. How can we hope for peace within a nation, While still based at Hartford, Buchman spent much of his time or between nations, when we have conflict in countless homes? travelling and forming groups of Christian students at Princeton Spiritual recovery must precede economic recovery. Political or University and Yale University, as well as Oxford. Sam Shoemaker, social solutions that do not deal with these root problems are a Princeton graduate and one-time Secretary of the Philadelphian inadequate." –Frank Buchman, “Remaking the World”, Blandford Society who had met Buchman in China, became one of his leading Press, 1947, (a collection of Frank Buchman’s speeches) American disciples. "We need a power strong enough to change human nature and Buchman designed a strategy of holding “house parties” at various build bridges between man and man, faction and faction. This locations, during which he hoped for Christian commitment starts when everyone admits his own faults instead of spotlighting among those attending. the other fellow's. God alone can change human nature. -

The Sound of Silence How to Find Inspiration in the Age of Information

The sound of silence How to find inspiration in tHe age of information Michael SMith The sound of silence How to find inspiration in tHe age of information caux Books isBn 978-1-56592-479-6 first published 2004 by Caux Books, 6th printing 2016 rue de panorama, Case postale 36, 1824 Caux, switzerland, Copyright © michael smith 2004, designed by Hayden russell, Cover photo by Chloe smith, Cartoons by einar engebretsen printed by impress print services Ltd, 19 Lyon road, Hesham, surrey Kt12 3pU, UK, [email protected] printed on environmentally friendly paper he age of Information has transformed the world, shrinking time and distance. Communication has become virtually instant. t The media bring the traumas and hopes of the world into our homes as they happen. We have access to almost unlimited information at the touch of our keyboards. We are more aware of the great social, moral and ethical issues the world faces than any previous generation, developing in us a strong social conscience. And social media keep us connected. Are we any wiser? We still face gross injustices between the rich and poor worlds, the scourge of deadly diseases, unprecedented environmental and family breakdown, climate change, racial and religious conflict, terrorism and war which fuel mass migration. We all too easily feel ineffective towards the issues the world faces and—unless we have access to the levers of economic and political power—unable to do anything about them. Yet we are more empowered to make a difference—to change the world—than in any previous age.