Introduction to Person-Centred Medicine: from Concepts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Tournier's Philosophy of Counseling As Developed from His Concept of Person Laurence H

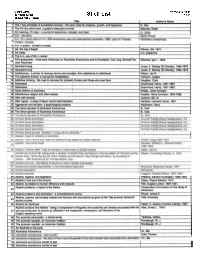

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Western Evangelical Seminary Theses Western Evangelical Seminary 5-1-1974 Paul Tournier's Philosophy of Counseling as Developed from His Concept of Person Laurence H. Wood PAUL TOURNIER 'S PHILOSOPHY OF COUNSELING AS DEVELOPED FROM HIS CONCEPT OF PERSON A Graduate Research Project Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Western Evangelical Seminary In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Divinity by Laurence H. Wood Jr. May 1974 APPROVED BY Major Professor: •.--t Lei{)~~~ 17::L .4"~p / TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. INTRODUCTION. 1 THE PROBLEM • 1 Statement of the Problem 1 Justification of the Problem 2 Limitation of the Study • 3 Definition of Key Terms • 4 SOURCES OF DATA • 5 STATEMENT OF ORGANIZATION • 5 2. THE LIFE AND WORK OF PAUL TOURNIER 7 Paul Tournier 1 s Parents • 8 The Early Years • 9 The Impersonal Years 10 The Years of Change and Growth 13 Doctor of Medicine of the Whole Person 17 The Productive Years. 21 Retirement Years 26 SUMMARY • 27 3 • THE MEANING OF PERSONS . 29 Personage and Person 29 The Failure of Science 33 Obstacles in the Search • 33 iii iv Chapter Page PROBLEMS IN FINDING THE PERSON 35 Utopia 35 The Example of Biology 37 Psychology and Spirit • 39 FINDING THE PERSON 41 The Dialogue 41 The Obstacle 43 The Living God 45 COMMITMENT TO THE PERSON 47 The World of Things and the World of Persons 47 To Live is to Choose 49 New Life 50 SUMMARY • 51 4 • THE PERSON REBORN 53 TECHNOLOGY AND FAITH 54 Technology or Faith • 55 Psychoanalysis and Soul-healing • 56 The Two Aspects of Man 57 Grace • . -

Faith for an Ideological Age

Journal of Eastern Christian Studies 61(3-4), 265-287. doi: 10.2143/JECS.61.3.2046975 © 2009 by Journal of Eastern Christian Studies. All rights reserved. FAITH FOR AN IDEOLOGICAL AGE THE MORAL AND RELIGIOUS IDEAS OF SEMYON FRANK AND FRANK BUCHMAN PHILIP BOOBBYER* INTRODUCTION The challenge of secular ideology in recent centuries has given rise to various forms of religious humanism that have sought to synthesise a Christian per- spective with social and political concerns. In the mid-20th century, religious thinkers sought alternatives to fascism, communism and materialistic capital- ism, as well as calling for reconciliation and reconstruction in a war-torn world. Two contrasting, yet at the same time intriguingly similar figures, the Russian philosopher, Semyon Liudvigovich Frank (1877-1950), and the American spiritual leader, Frank Buchman (1878-1961), are the focus of this study. Although from a Jewish background, Semyon Frank was a convert to Orthodoxy. One of Russia’s so-called “legal Marxists”, he became a promi- nent intellectual opponent of revolutionary socialism, and was amongst the elite group of thinkers exiled from the USSR in 1922 on the so-called “phi- losophy steamer”.1 In exile he warned of the threats to Western democracy from both communism and materialism, and formulated, particularly in the 1940s, a social and political philosophy rooted in religious principles.2 Frank Buchman, the founder of the movement known as the Oxford Group and then Moral Re-Armament, came from a very different background. Born into a Lutheran, Pennsylvania Dutch family, he was shaped by the culture of East Coast American evangelism, as well as the Keswick movement. -

The Meaning of Gifts by Paul Tournier Christmas in Japan and Cameroon

The Meaning of Gifts Christmas in Japan Liberating Christ from Christmas December 1969 by Paul Tournier and Cameroon by Richard John Neuhaus by Lucille Wipf/ Peter Fehr Bop istHerold Volume 47 December 1969 No. 20 The Meaning of Gifts, Paul Tournier, 4 Christmas in Japan, Lucille Wipf, 6 Christmas in Cameroon, Peter Fehr, 7 History of the Baptist Herald, M. L. Leuschner, 8 A Post-Christmas Prayer, Charles Waugaman, 12 Valley View Baptist Plans to Organize and Build, Herbert Vetter, 13 Love is a Feeling, Walter Trobisch, 14 Liberating Christ from Christmas, John Neuhaus, 15 Coming World Peace and Evangelism, Mark H atfield, 18 An Agnostic and Christmas, 21 Baptist Herald Index, January to December 1969, 26 Ask the Professor, Gerald Borchert, 10 God's Volunteers, JO Youth Scene, Bruce Rich, 11 Book Reviews, B. C. Schreiber, 12 We the Women, Mrs. Herbert Hiller, 22 Insight Into Christian Education, edited by Dorothy Pritzkan; Children are Natural Believers, Ervin Gerlitz, 23 Bible Study, James Schacher, 24 Our Churches in Acti on, 28 In Memoriam, 31 News & Views, 32 As I See It, Paul Siewert, 32 What's Happening, 32 Editori al: A New Look, Sharing the Christmas Event, 34 Open Dialogue, 34 Mo111hlv Puhlication of the Editor: Joh n Binder o f the · North A 1ll!·rica11 Baptist Editorial Assis/a/I/: Bruno Schreiber /?ager IVilliwm Press G eneral Conference Business M anager: Eldon Janzen HOPE. 7 308 /\fadisnn Street l:."ditMial Co111 111ittee: John Bi11der the promise of Christmas Forest Park. Illinois 60130 G rrhard Panke. Arthur Garling PEACE . the message of Christmas Gl'rald Borchert. -

Current Background Theology

A Synopsis of the Theological Systems Behind Current UK Church Streams How to see the wood for the trees in today’s evangelical mess. Paul Fahy 2 A Synopsis of the Theological Systems Behind Current UK Church Streams Contents Why is this important? Amyraldism Arminianism Calvinism / Reformed Theology Cessationism Charismatic Theology / Neo Pentecostalism Deeper Life / Higher Life / Victorious Life / Keswick Teachings Deliverance Theology Dominionism 1: Reconstructionism / Theonomy Dominionism 2: Charismatic Kingdom Theology Dispensationalism [Dispensational Premillennialism] Ecumenical Theology & Movements The Emerging Church Federal Vision Fullerism Hyper-Calvinism Humanism Jewish Roots Liberal Theology Modernism Mysticism / New Age New (or Neo) Evangelicalism Neo Orthodoxy [Dialectical Theology or The New Hermeneutic] The New Perspective on Paul / Justification / Judaism Oberlin Theology (Finneyism) / New Haven Theology / New Divinity Occult Theology / Paganism Open Theism Pentecostalism Perfectionism Psychoheresy Quietism Sacramentalism Seeker-sensitive Practices / Church Growth Movement Strategic Level Spiritual Warfare Theology / Territorial Spirits Universalism - No hell as future punishment Conclusion 3 Appendixes Appendix One: The Progress of Charismatic Error Appendix Two: The Jewish Roots Reaction to Extreme Charismaticism Appendix Three: The Eschatological Key to Current Charismatic Factions Appendix Four: The Diminishing of the authority of God’s Word Appendix Five: The Impact of the Mind Sciences Appendix Six: The Rise of -

Shelf List 1/18 East Dorset VT 05253 Title Author's Name 1 the 7 Key Principles of Successful Recovery: the Basic Tools for Progress, Growth, and Happiness B., Mel

Griffith Library 07/25/0514:13:40 38 Village Street Shelf List 1/18 East Dorset VT 05253 Title Author's Name 1 The 7 key principles of successful recovery: the basic tools for progress, growth, and happiness B., Mel. 2 The 24 hour drink b~u!de to executive survival. Maloney, Ralph. --- 61 A.A. in prison: inmate to inmate. 71 AA, the way it began I Pittman, Bill, 1947-_1 way of life; a reader 10I AA's godparents: three early influences on Alcoholics Anonymous and its foundation, Carl Jung, Emmet Fox, Sikorsky, Igor I., 1929- I Jack Alexander 11 Abundant living Jones, E. Stanley (Eli Stanley), 1884-1973:l 12 Abundant living Jones, E. Stanley (Eli Stanley), 1884-1973. I 13 Addictionary: a primer of recovery terms and concepts, from abstinence to withdrawal Wilson, Jan R. I 14 The addictive drinker; a manual for rehabilitation. Thimann, Joseph. I 15 Addictive drinking: the road to recovery for problem drinkers and those who love them Vaughan, Clark. I 16 Addresses Drummond, Henry, 1851-1897. 171 Addresses I Drum~o_nd._Henry. 1851-~~97. 181 Adult children of alcohoTi-cs ~ Woititz, Janet Geringer. 191 Adventurous religion and other essays Fosdick, Harry Emerson, 1878-1969. 20 Afire with serenity Jackson, Bill, Dr. 21 After repeal: a study of liquor control administration Harrison, Leonard Vance, 1891- 22 Aggression and altruism, a psychological analysis. Kaufmann, Harry. 23 The Akron genesis of Alcoholics Anonymous B., Dick. 24 The Akron qenesis of Alcoholics Anonymous B. Dick. Alcohol, hygiene, and legislation EdwardHu~ington!~~ 411 Alcohol in and out of the church lOates,_~ayne Edward, 1917- ~IXcohof; Its relation to human efficiency and longevity Fisk, Eugene Lyman, 1867-1931.~ Alcohol problems; a report to the Nation. -

Comments on the Dutch Edition

Comments on the Dutch edition Paul Nouwen in his foreword to the Dutch edition: ‘In this beautiful description we follow how the search of the movement went. I hope the readers of this book will feel strengthened to promote the changes that are needed and to help people around them.’ Katholiek Nieuwsblad: ‘The ideal to forgive for a better world is still of paramount importance... a near revolutionary thought in the Netherlands of today.’ Friesch Dagblad: ‘This book is honest and it holds a mirror for the reader. It describes the essence of the movement, without being yet another catechism. The principles come together in the Golden Rule: Treat others as you want them to treat you.’ Bert Endedijk, publisher of the book in the Netherlands, director of Kok/ten Have: ‘The author describes an important movement. She places herself in a vulnerable position by looking critically at the movement which is dear to her.’ Father Bert ten Berge, SJ: ‘This book was my spiritual reading for my retreat. It gave me a lot of food for thought.’ Reaching for a new world Initiatives of Change seen through a Dutch window Hennie de Pous-de Jonge CAUX BOOKS First published in 2005 as Reiken naar een nieuwe wereld by Uitgeverij Kok – Kampen The Netherlands This English edition published 2009 by Caux Books Caux Books Rue de Panorama 1824 Caux Switzerland © Hennie de Pous-de Jonge 2009 ISBN 978-2-88037-520-1 Designed and typeset in 10.75pt Sabon by Blair Cummock Printed by Imprimerie Pot, 78 Av. des Communes-Réunies, 1212 Grand-Lancy, Switzerland Contents Preface -

Lived Religion and the Changing Spirituality and Discourse of Christian Globalization: a Canadian Family's Odyssey

Lived Religion and the Changing Spirituality and Discourse of Christian Globalization: A Canadian Family’s Odyssey MARGUERITE VAN DIE Queen’s University Few individuals have presented a greater challenge to a secular society’s understanding of the past than the missionary. “Once almost universally acclaimed as a self-sacrificing benefactor, he or she is now more com- monly dismissed as an interfering busybody and in all probability a misfit at home who could find only among the colonized a captive audience on whom to impose a narrow set of beliefs and moral taboos.”1 Thankfully, in the three decades since this memorable characterization by Canadian church historian John Webster Grant, research into related areas such as gender and theological change has done much to deconstruct these stereotypes. Recent work on Christian globalization has moreover drawn attention to the ways the missionary enterprise changed religion not simply among the indigenous population, but also at home. Mark Noll, for example, has argued that by the early twentieth century as part of a larger global “multi-centering,” Christianity in North America was subtly shifting away from traditional church and imperial norms towards new models. It is now generally accepted that this re-centering was accompa- nied by an enormous release of evangelical energy, and the impact of an emerging global society profoundly reshaped Christianity.2 My essay builds on Noll’s observations, but rather than focusing on missionary institutions and their spokespersons, it examines from below some of the continuities and changes in the spirituality and discourse of Christian globalization. It does this within the context of three generations Historical Papers 2015: Canadian Society of Church History 114 Spirituality and Discourse of Christian Globalization of a well-to-do Toronto family for whom missions and international travel were a compelling way of life. -

Inspire, Equip and Connect for Change

Inspire, equip and connect for change Annual Report 2015 CAUX-INITIATIVES OF CHANGE FOUNDATION TABLE OF CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT 6 ABOUT US 7 THE CAUX-IOFC FOUNDATION 7 THE CAUX CONFERENCES 10 ACTIVITIES OF THE FOUNDATION 11 DIALOGUE, PEACE AND RECONCILIATION: BUILDING TRUST ACROSS THE WORLD’S DIVIDES 11 ETHICAL LEADERSHIP: PUTTING THE ETHICS BACK INTO BUSINESS 19 EXPLORING THE HUMAN FACTOR IN ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY 23 EMPOWERING THE NEXT GENERATION OF CHANGEMAKERS 26 ENGAGING WITH LOCAL AND INTERNATIONAL STAKEHOLDERS 31 INITIATIVES OF CHANGE NETWORK 32 MAINTAINING THE LEGACY: THE CAUX CONFERENCE CENTRE 33 ARCHIVES 34 CAUX BOOKS 34 FOUNDATION NEWS 35 FINANCIAL STATEMENT 37 ORGANIZATION 39 2 The CAUX-Initiatives of Change Foundation Annual Report 2015 The Caux Palace Annual Report 2015 The CAUX-Initiatives of Change Foundation 3 Antoine Jaulmes, President of the CAUX-IofC Foundation MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT n 2015, the international community weathered a storm rise to dialogue not only between Russians and Ukrainians, of concern and emotion. It was so torrential that it almost but also between Armenians and Turks – coinciding with Ioverwhelmed the very notion of peace and dialogue the centenary of the Armenian genocide – on their shared promotion, of global and personal accountability and of history and its impact on their daily lives. The success of ethics in our daily lives and society. The endeavour of these events would not have been possible without the the CAUX-IofC Foundation appeared however even more generosity of the donor community and the enthusiasm of needed than ever before: its Caux Palace offers a unique our staff and volunteers. -

Summary Report

GENEVA CONFERENCE ON PERSON- CENTERED MEDICINE May 29 – 30, 2008 L’ Auditoire Marcel Jenny, University Hospitals of Geneva Organized by the World Psychiatric Association Institutional Program on Psychiatry for the Person (IPPP) in collaboration with the World Medical Association (WMA), the World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA), the World Federation of Neurology (WFN), the World Federation for Medical Education (WFME), the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), the World Federation for Mental Health (WFMH), the International Council of Nurses (ICN), and the International Alliance of Patients’ Organizations (IAPO), with the cooperation of the Paul Tournier Association, and the auspices of the University Hospitals of Geneva (HUG). Conference Summary Report Conference President J.E. Mezzich Conference Coordinator M. Botbol Rapporteurs I. Salloum and T. Sensky Organizational Support IPPP Leadership (J.E. Mezzich, G. Christodoulou, B. Fulford, I. Salloum, R. Montenegro, A. Tasman, T. Sensky, H. Herrman, M. Amering), Geneva Task Force (J. Cox, F. Ferrero, O. Kloiber, B. Ruedi, H-R Pfeifer, A. Engstrom, P. Atiase), WPA President New York Office (E. Millan, M. Han), and unrestricted grants from Johnson & Johnson and the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Geneva Conference on Person-centered Medicine is the latest event in the unfolding WPA Psychiatry for the Person programmatic process, which also includes a London Conference in October 2007 and -

The Worldwide Legacy of FRANK BUCHMAN

The Worldwide Legacy of FRANK BUCHMAN Compiled by Archie Mackenzie & David Young CAUX BOOKS INITIATIVES OF CHANGE First published 2008 by Caux Books rue de Panorama, 1824, Caux, Switzerland; www.caux.ch and Initiatives of Change 24 Greencoat Place, London SW1P 1RD; www.iofc.org © Caux Books ISBN 2-88037-517-7 978-2-88037-517-1 Cover design by John Munro Typesetting and text design in 10.5 Sabon by Blair Cummock Printed by Biddles, King’s Lynn, Norfolk ii Contents Foreword Archie Mackenzie & David Young 7 Introduction Archie Mackenzie 9 1. How Caux began 38 Pierre Spoerri 2. France and the Expansion of Buchman’s Faith 51 Michel Sentis 3. A German Veteran remembers 65 Hansjörg Gareis 4. Hidden ingredients of Japan’s post-war Miracle 81 Fujiko Hara for Yukika Sohma 5. Human Torpedo turns Creative Consultant 87 Hideo Nakajima 6. Seeds of Change for Africa 98 Peter Hannon, Suzan Burrell, Amina Dikedi-Ajakaiye & Ray Purdy 7. Frank Buchman’s legacy in French-speaking Africa 120 Frédéric Chavanne 8. Political Dynamite in Australia 135 Mike Brown & John Bond 9. India’s Journey towards New Governance 148 V C Viswanathan 10. Ordinary Brazilians doing Extraordinary things 167 Luis Puig iii 11. Buchman’s Inspired Ideology for America 174 Jarvis Harriman, Bob Webb & Dick Ruffin 12. Clean Elections – Target for Taiwan 198 Ren-Jou Liu & Brian Lightowler 13. Frank Buchman and the Muslim World 206 Imam Abduljalil Sajid 14. Action emerges from Silence – a Russian view 219 Grigory Pomerants 15. Industry’s Forgotten Factor 229 Alec Porter with Jens Wilhelmsen, Maarten de Pous & Miles Paine 16. -

Paul Tournier

International Journal of Integrated Care – ISSN 1568-4156 Volume 10, 29 January 2010 URL: http://www.ijic.org Publisher: Igitur, Utrecht Publishing & Archiving Services Copyright: Section on Honoring Paul Tournier Paul Tournier and ‘Médecine de la Personne’— The man and his vision Hans-Rudolf Pfeifer, Paul Tournier Association, www.paultournier.org, Zurich, Switzerland Correspondence to: Hans-Rudolf Pfeifer, E-mail: [email protected] Introduction Paul Tournier (1898–1986), physician and writer from Geneva, Switzerland, made an outstanding pioneering con- tribution to the understanding and practice of an integrative approach of medicine, psychology and pastoral coun- selling, which had an impact on many professionals and laymen alike in all continents. He was the founder of ‘Médecine de la Personne’ (‘Medicine of the Person’) [1]. His work and his message is best understood against the background of his biography. His attitude and challenge were derived from his own experiences and insights, yet even today seem equally valid for health care systems across the world that are striving to meet the wish of patients and service users for more person-centered and holistic health care. Early biography Paul Tournier became an orphan after his father, pastor of the Geneva Cathedral, had died shortly after Paul’s birth and his mother had died from breast cancer when Paul was only six years. He described the feeling of painful emp- tiness and vanishing into nothingness, afraid of being totally insignificant to anybody in the future. He grew up with his aunt and uncle, a businessman. Unable to accept affection, he withdrew into himself and had no friends.