Mauritania Vegetable Production Project P,\- -,A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Project: Rosso Bridge Construction Project Country: Multinational Senegal-Mauritania Summary of the Full Resettlement Plan (Frp)

Rosso Bridge Construction Project FRP SUMMARY AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT: ROSSO BRIDGE CONSTRUCTION PROJECT COUNTRY: MULTINATIONAL SENEGAL-MAURITANIA SUMMARY OF THE FULL RESETTLEMENT PLAN (FRP) Project Team A.I. MOHAMED, Principal Transport Economist, OITC.1/SNFO M. A. WADE, Infrastructure Expert, OITC/SNFO P-M. NDONG, Transport Engineer, OITC.2 / MAFO L. EHOUMAN, Principal Socio-Economist, OITC.1 L.C. KINANE, Principal Environmentalist, ONEC.3 Project S. BAIOD, Consultant Environmentalist, ONEC.3 Team Sector Director A. OUMAROU Regional Director: A. BERNOUSSI Resident Representative: M. NDONGO Division Manager: J.K. KABANGUKA 1 Rosso Bridge Construction Project FRP SUMMARY Project Title : ROSSO BRIDGE CONSTRUCTION PROJECT Country : MULTINATIONAL SENEGAL-MAURITANIA Project Number : P-Z1-D00-020 Department : OITC Division: OITC.1 INTRODUCTION This document is a summary of the Full Resettlement Plan (FRP). In accordance with the national procedures of Senegal and Mauritania and those of the Bank, a full resettlement plan was developed. This FRP covers the compensation and resettlement of project-affected persons (PAPs). Its objectives are to: (i) limit involuntary displacement to the extent possible; (ii) reduce property destruction to the extent possible; and (iii) compensate PAPs for the loss of homes, farms, built-up structures and facilities, and income. 1. SUMMARY DESCRIPTION AND PROJECT LOCATION 1.1 Project Description The construction of a bridge over the Senegal River in Rosso and the implementation of transport facilitation measures will provide a permanent crossing facility over the river, and play a decisive role in developing the interconnection of regional road networks. It will be an important link that promotes integration and trade development between the countries of the Arab Maghreb Union, West Africa and probably beyond. -

Evaluation and Assessment of Meteorological Drought by Different Methods in Trarza Region, Mauritania

Water Resour Manage (2017) 31:825–845 DOI 10.1007/s11269-016-1510-8 Evaluation and Assessment of Meteorological Drought by Different Methods in Trarza Region, Mauritania Ely Yacoub1 & Gokmen Tayfur1 Received: 6 June 2016 /Accepted: 20 September 2016 / Published online: 10 October 2016 # Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2016 Abstract Drought Indexes (DIs) are commonly used for assessing the effect of drought such as the duration and severity. In this study, long term precipitation records (monthly recorded for 44 years) in three stations (Boutilimit (station 1), Nouakchott (station 2), and Rosso (station 3)) are employed to investigate the drought characteristics in Trarza region in Mauritania. Six DI methods, namely normal Standardized Precipitation Index (normal-SPI), log normal Standardized Precipitation Index (log-SPI), Standardized Precipitation Index using Gamma distribution (Gamma-SPI), Percent of Normal (PN), the China-Z index (CZI), and Deciles are used for this purpose. The DI methods are based on 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12 month time periods. The results showed that DIs produce almost the same results for the Trarza region. The droughts are detected in the seventies and eighties more than the 1990s. Twelve drought years might be experienced in station 2 and six in stations 1 and 3 in every 44 years, according to reoccurrence probability of the gamma-SPI and log-SPI results. Stations 1 and 3 might experience fewer drought years than station 2, which is located right on the coast. In station 1, which is located inland, when the annual rainfall is less than 123 mm, it is likely that severe drought would occur. -

Wvi Mauritania

MAURITANIA ZRB 510 – TVZ Nouakchott – BP 335 Tel : +222 45 25 3055 Fax : +222 45 25 118 www.wvi.org/mauritania PHOTOS : Bruno Col, Coumba Betty Diallo, Ibrahima Diallo, Moussa Kante, Delphine Rouiller. GRAPHIC DESIGN : Sophie Mann www.facebook.com/WorldVisionMauritania Annual Report 2016 MAURITANIA SUMMARY World Vision MAURITANIA 02 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 World Vision Mauritania in short . .04 A word from the National Director . .05 Strategic Objectives . .06 Education . .08 Health & Nutrition . .12 WASH . .14 Emergencies . .16 Economic Development . .22 Advocacy . .24 Faith and Development . .26 Highlights . .28 Financial Report . .30 Partners . .32 World Vision MAURITANIA 03 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 4 ALGERIA Areas of 14 interventions Programms TIRIS ZEMMOUR WESTERN SAHARA 261 Zouerat Villages 6 Nouadhibou partners PNS ADRAR DAKHLET Atar NOUADHIBOU INCHIRI Akjoujt World Vision Mauritania TAGANT HODH Nouakchott Tidjikdja ECH has a a staff of 139 including CHARGUI ElMira IN SHORT TRARZA 31 women with key positions BRAKNA in almost every department Aleg Ayoun al Atrous Rosso ASSABA Néma Kiffa GORGOL HODH Kaedi EL GHARBI GUDIMAKA Selibaby SENEGAL MALI World Vision MAURITANIA 04 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 A WORD FROM THE NATIONAL DIRECTOR Dear readers, I must hereby pay tribute to the Finally, I can’t forget our projects professional spirit of our program teams that have worked World Vision Mauritania has, by teams that work without respite constantly to raise projects’ my voice, the pleasure to present to mobilize and prepare our local performances to a level that can you its annual report that gives community partners. guarantee a better impact. We an overview on its achievements can’t end without thanking the through the 2016 fiscal year. -

African Development Bank Group Project : Mauritania

Language: English Original: French AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT : MAURITANIA – AGRICULTURAL TRANSFORMATION SUPPORT PROJECT (PATAM) COUNTRY : ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF MAURITANIA PROJECT APPRAISAL REPORT Main Report Date: November 2018 Team Leader: Rafâa MAROUKI, Chief Agro-economist, RDGN.2 Team Members: Driss KHIATI, Agricultural Sector Specialist, COMA Beya BCHIR, Environmentalist, RDGN.3 Sarra ACHEK, Financial Management Specialist, SNFI.2 Saida BENCHOUK, Procurement Specialist, SNFI.1-CODZ Elsa LE GROUMELLEC, Principal Legal Officer, PGCL.1 Amel HAMZA, Gender Specialist, RDGN.3 Ibrahima DIALLO, Disbursements Expert, FIFC.3 Project Selima GHARBI, Disbursements Officer, RDGN/FIFC.3 Team Hamadi LAM, Agronomist (Consultant), AHAI Director General: Mohamed EL AZIZI, RDGN Deputy Director General: Ms Yacine FAL, RDGN Sector Director: Martin FREGENE, AHAI Division Manager: Vincent CASTEL, RDGN.2 Division Manager: Edward MABAYA, AHAI.1 Khaled LAAJILI, Principal Agricultural Economist, RDGC; Aminata SOW, Rural Peer Engineering Specialist, RDGW.2; Laouali GARBA, Chief Climate Change Specialist, Review: AHAI.2; Osama BEN ABDELKARIM, Socio-economist, RDGN.2. TABLE OF CONTENTS Equivalents, Fiscal Year, Weights and Measures, Acronyms and Abbreviations, Project Information Sheet, Executive Summary, Project Matrix ……….…………………...………..……... i - v I – Strategic Thrust and Rationale ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Project Linkage with Country Strategy and -

World Bank Document

Document of THE WORLD BANK Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 17396-MAR, PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A Public Disclosure Authorized PROPOSED INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION CREDIT IN AN AMOUNT OF US$24 MILLION TO THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF MAURITANIA FORA Public Disclosure Authorized HEALTH SECTOR INVESTMENT PROJECT February 24, 1998 Public Disclosure Authorized Human Development II Africa Region CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange rate effective as of December 22, 1997) Currency Unit = UM I UM US$0.006353 US$1 157.41 UM FISCAL YEAR January I to December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AfDB - African Development Bank AIDS - Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome ARI - Acute Respiratory Infections BCI - Budget consolide d'investissements (Public Investment Budget) BHA - Better Health in Africa CAS - Country Assistance Strategy CDC - Center for Disease Control CGP - Comitetde gestion du programme (Program Management Committee) CHN - Centre hospitalier national (National Hospital Center) CPF - Centre de promotion feminine (Center for the Promotion of Women) CPP - Commission de preparation du PASS (Project Preparation Committee) CSA - Centre de sante cate,gorieA (Health center category A) CSB - Centre de sante categorie B (Health center category B) CSPD - Commission chargee du suivi et de la mise en oeui re du Plan Directeur 1998-2002 (Sector Policy Implementation Board) DAAF - Direction des affaires administratives etfinancieres (Directorate of Administrative and Financial Affairs) DALY - Disability Adjusted Life-Year DGI - Direction de -

It. S.A.I.D./O.M.V.S. Integrated Development Project Project No

IT. S.A.I.D./O.M.V.S. INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PROJECT PROJECT NO. 6M-0621 VOLUME III SECTION 3.3. ANALYSIS OF THE IDP TRAINING COMPONENT USAID/RBDO OCTOBER 1982 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 3.3. ANALYSIS OF THE IDP TRAINING COMPONENT 3.3.1. Objectives ............................ 1 3.3.1.1. General Objectives ..... ..................I... 1 3.3.1.2. Specific Objectives ...... .. ................ 2 3.3.1.2.1. Long-term Objectives 2.........2 3.3.1.2.2. Short-term Objectives .... ......... 2 3.3.2. Perceived Problems ...... .... ..................... 3 3.3.2.1. Farmer Training ..... .... ................. 3 3.3.2.2. Common Institutional and Implementation Problems 3 3.3.3. Overview of the Proposed IDP Training Strategies ... ....... 4 3.3.3.1. Introduction ...... ..... .................. 4 3.3.3.2. Strategy at the Village Level ..... ........... 6 3.3.3.2.1. The Farmers' Associations 6.......6 3.3.3.2.2. The Farmers ..... .. .............. 7 3.3.3.3. Strategy at the RDA Level ...... ............. 8 3.3.4. Organization of Training at the RDA's Level: Training 9 and Monitoring Personnel 3.3.4.1. Training Personnel: Role and Functions of the 9 TA Staff 3.3.4.2. Training of the RDA Extension Personnel ......... 10 3.3.4.2.1. Need for Training .......... 10 3.3.4.2.2. Personnel: Categories and Type of 11 Training Needed 3.3.4.2.3. Contents, Methodology and Sources Needed 12 3.3.4.3. The Mobile Training Unit (fTU) .. .......... ... 16 3.3.4.3.1. Organization cf the MTU ........ 16 3.3,4.3.2. Tasks of the fU .......... -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Rapport initial du projet Public Disclosure Authorized Amélioration de la Résilience des Communautés et de leur Sécurité Alimentaire face aux effets néfastes du Changement Climatique en Mauritanie Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable ID Projet 200609 Date de démarrage 15/08/2014 Public Disclosure Authorized Date de fin 14/08/2018 Budget total 7 803 605 USD (Fonds pour l’Adaptation) Modalité de mise en œuvre Entité Multilatérale (PAM) Public Disclosure Authorized Septembre 2014 Rapport initial du projet Table des matières Liste des figures ........................................................................................................................................... 2 Liste des tableaux ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Liste des acronymes ................................................................................................................................... 3 Résumé exécutif ........................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. Historique du projet ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2. Concept du montage du projet .................................................................................................. -

Mauritania Country Portfolio

Mauritania Country Portfolio Overview: Country program established in 2008. USADF currently U.S. African Development Foundation Partner Organization: IDSEPE manages a portfolio of 16 projects. Total commitment is $1.6 million. Country Program Coordinator: Mr. Sadio Diarra Abdoul Dakel Ly, Project Coordinator BMCI/AFARCO building, 6th floor Tel: +222 44 70 27 27 & +222 22 30 35 04 Country Strategy: The program focuses on working with Avenue Gamal Abder Nassar Email: [email protected] agricultural groups and women’s collectives. P.O Box 1980, Nouakchott, Mauritania Tel: +222 525 29 36 Email: [email protected] Grantee Duration Value Summary Lithi Had El Amme / Iguini El Oula 2014-2017 $94,243 Sector: Agriculture (Vegetables) 3023-MRT Town/City: Wilaya Hodhs -El- Gharbi Summary: The project funds will be used to ensure a reliable water supply to the garden by setting up a borehole extraction system. Funds will allow the Union to expand their cultivation plot to 2 hectares by installing a new irrigation system and building a fence around it to protect it from roaming animals.. Coopérative El Emen Berbâré 2014-2017 $85,527 Sector: Agriculture (Vegetables) 3163-MRT Town/City: Wilaya Hodhs -El- Gharbi Summary: The project funds will be used to install a new irrigation system and fence it to protect it from roaming animals. The Cooperative will set up a borehole extraction system to provide a reliable and constant source of water to the production perimeter. These activities will enable Cooperative members to dramatically increase the volume of vegetables sold and the profit earned by group members. -

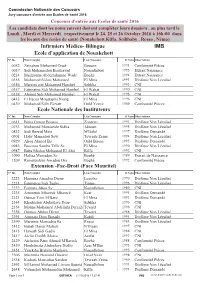

Infirmiers Médico- Bilingue IMB Ecole D'application De Nouakchott Ecole

Commission Nationale des Concours Jury concours d’entrée aux Ecoles de santé 2016 Concours d'entrée aux Ecoles de santé 2016 Les candidats dont les noms suivent doivent compléter leurs dossiers , au plus tard le Lundi , Mardi et Mercredi respectivement le 24, 25 et 26 Octobre 2016 à 16h:00 dans les locaux des écoles de santé (Nouakchott,Kiffa, Seilibaby , Rosso , Néma) Infirmiers Médico- Bilingue IMB Ecole d'application de Nouakchott N° Ins Nom Complet Lieu Naissance D Naiss Observations 0052 Zeinabou Mohamed Cissé Bouanz 1991 Conformité Pièces 0057 Sidi Mohamedou Bouleayad Nouadhibou 1995 Extrait Naissance 0214 Maimouna Abderrahmane Wade Boghé 1994 Extrait Naissance 0355 Mohamed Sidaty Mohamed El Mina 1993 Diplôme Non Légalisé 0356 Mareim sidi Mohamed Hambel Sebkha 1993 CNI 0357 Fatimetou Sidi Mohamed Hambel El Wahat 1990 CNI 0358 Ahmed Sidi Mohamed Hambel El Wahat 1996 CNI 0413 El Hacen Moustapha Niang El Mina 1996 CNI 0439 Mohamed Silly Eleyatt Ould Yengé 1989 Conformité Pièces Ecole Nationale des Instituteurs N° Ins Nom Complet Lieu Naissance D Naiss Observations 0611 Binta Oumar Bousso Zoueratt 1993 Diplôme Non Légalisé 0753 Mohamed Mousseide Sidha Akjoujt 1995 Diplôme Non Légalisé 0832 Sidi Bezeid Mein M'Balal 1997 Diplôme Demandé 0901 Haby Mamadou Sow Tevragh Zeina 1994 Diplôme Non Légalisé 0929 Aliou Ahmed Ba Ould Birom 1995 Diplôme Demandé 0983 Bassirou Samba Tally Sy El Mina 1990 Diplôme Non Légalisé 0987 Baba Medou Mohamed El Abd Kiffa 1992 CNI 1090 Hafssa Mamadou Sy Boghé 1989 Extrait de Naissance 1209 Ramatoulaye Amadou Dia -

147AV4-1.Pdf

بسم هللا إلرمحن إلرحمي إمجلهورية إ لسﻻمية إملوريتانية رشف إخاء عدل إلوزإرة إ ألوىل إلس نة إجلامعية 2019-2018 إللجنة إلوطنية للمسابقات جلنة حتكمي إملسابقة إخلارجية لكتتاب 240 وحدة دلخول إملدرسة إلعليا للتعلمي حمرض مدإولت إلتأأمت جلنة حتكمي إملسابقة إخلارجية لكتتاب 240وحدة دلخول إملدرسة إلعليا للتعلمي، يــــوم إلسبت إملوإفق 08 دمجرب 2018 عند إلساعة إلثانية عرشةزوالا يف قاعة الاجامتعات ابملدرسة إلعليا للتعلمي؛ حتت رئاســـة إلسيـــد/ أبوه ودل محمدن ودل بلبﻻ ،ه انئب رئيس إللجنة - وحبضــور أإلعضاء إملعنيني، وبعد تقدمي إلسكراتراي لنتاجئ إملسابقة أابلرقـــــام إلومهية مرتبة ترتيبا إس تحقاقيا، ذكرت إلسكراتراي جلنة إلتحكمي بعــدد إملقاعد إملطلوبة من لك شعبة، وبعد نقاش مس تفيض لنتاجئ لك بةشع عىل حدة مت إعﻻن إلناحجني حسب إلرتتيب الاس تحقايق يف لك شعبة، فاكنت إلنتاجئ عىل إلنحو إلتايل : أول : أساتذة إ لعدإدية : I- Professeurs de Collège - شعبة : إلعربية وإلرتبية إ لسﻻمية - (Ar+IR) - إلناجحون حسب إلرتتيب إ لس تحقايق Liste des admis par ordre de mérite - إلرتتيب رمق إلندإء إ لمس إلاكمل اترخي وحمل إمليﻻد إملﻻحظات إ لس تحقايق 1 0141 يحظيه النعمة اباه 1993/12/31 تنحماد 2 0001 عبد الرحمن محمدن موسى سعدنا 1991/12/31 تكند 3 0722 امنه محمد عالي ببات 1987/08/10 السبخة 4 0499 عبد الرحمن محمد امبارك القاضين 1993/01/01 السبخه 5 0004 الغالي المنتقى حرمه 1992/12/31 اوليكات 6 0145 محمد سالم محمدو بده 1984/12/04 الميسر 7 1007 محمد عالي محمد مولود الكتاب 1996/09/03 العريه 8 0536 ابد محمد سالم محمد امبارك 1992/12/31 بتلميت 9 0175 محمد محمود ابراهيم الشيخ النعمه 1982/10/29 اﻻك 10 0971 الطالب أحمد جدو سيد إبراهيم حمادي 1995/12/16 اغورط 11 0177 محمد اﻻمين احمد شين 1982/12/31 -

Regionalization of Research in West and Central Africa a Synthesis of Workshop Findings and Recommendations

SD Publication Series Office of Sustainable Development Bureau for Africa Regionalization of Research in West and Central Africa A Synthesis of Workshop Findings and Recommendations Banjul, The Gambia March 14–16, 1994 Technical Paper No.4 November 1994 Regionalization of Research in West and Central Africa A Synthesis of Workshop Findings and Recommendations Banjul, The Gambia March 14–16, 1994 Publication services provided by AMEX International, Inc. pursuant to the following USAID contract: Project Title: Policy, Analysis, Research, and Technical Support Project Project Number: 698-0478 Contract Number: AOT-0478-C-00-3168-00 CORAF Conférence des Responsables Special Program for African U.S. Agency for International de Recherche Agronomique Agricultural Research Development Africaine Bureau for Africa i ii Contents Foreword v Executive Summary vi Glossary of Acronyms and Abbreviations ix 1. Introduction 1 A. The Workshop 1 B. Objectives 1 2. Background 2 A. Regionalization of Research 2 B. The Framework for Action for the Humid and Sub Humid Zones of Central 3 and Western Africa C. Coordination of Regional Research Programs 3 D. Impacts from Agricultural Research 4 E. Future Challenges: Trade and Technology 5 3. Recommendations 6 A. Governance and Coordination 6 B. Institutional Mechanisms to Fund and Implement Programs 6 C. Strategic Planning and Priority Setting 7 D. Technical Forum and Information Exchange 7 4. Follow-up Actions 9 Annexes A. List of Documents/Liste des Documents 10 B. List of Participants/Liste des Participants 13 C. Agenda 24 D. Regional Programs Synopsis 30 iii iv Foreword In Africa and within the international commu- tional, regional, and international activities in nity, a shared vision of an Africa on the path to West and Central Africa. -

Mauritania 20°0'0"N Mali 20°0'0"N

!ho o Õ o !ho !h h !o ! o! o 20°0'0"W 15°0'0"W 10°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 0°0'0" Laayoune / El Aaiun HASSAN I LAAYOUNE !h.!(!o SMARAÕ !(Smara !o ! Cabo Bu Craa Algeria Bojador!( o Western Sahara BIR MOGHREIN 25°0'0"N ! 25°0'0"N Guelta Zemmur Ad Dakhla h (!o DAKHLA Tiris Zemmour DAJLA !(! ZOUERAT o o!( FDERIK AIRPORT Zouerate ! Bir Gandus o Nouadhibou NOUADHIBOU (!!o Adrar ! ( Dakhlet Nouadhibou Uad Guenifa !h NOUADHIBOU ! Atar (!o ! ATAR Chinguetti Inchiri Mauritania 20°0'0"N Mali 20°0'0"N AKJOUJT o ! ATLANTIC OCEAN Akjoujt Tagant TIDJIKJA ! o o o Tidjikja TICHITT Nouakchott Nouakchott Hodh Ech Chargui (!o NOUAKCHOTT Nbeika !h.! Trarza ! ! NOUAKCHOTT MOUDJERIA o Moudjeria o !Boutilimit BOUTILIMIT ! Magta` Lahjar o Mal ! TAMCHAKETT Aleg! ! Brakna AIOUN EL ATROUSS !Guerou Bourem PODOR AIRPORTo NEMA Tombouctou! o ABBAYE 'Ayoun el 'Atrous TOMBOUCTOU Kiffa o! (!o o Rosso ! !( !( ! !( o Assaba o KIFFA Nema !( Tekane Bogue Bababe o ! o Goundam! ! Timbedgha Gao Richard-Toll RICHARD TOLL KAEDI o ! Tintane ! DAHARA GOUNDAM !( SAINT LOUIS o!( Lekseiba Hodh El Gharbi TIMBEDRA (!o Mbout o !( Gorgol ! NIAFUNKE o Kaedi ! Kankossa Bassikounou KOROGOUSSOU Saint-Louis o Bou Gadoum !( ! o Guidimaka !( !Hamoud BASSIKOUNOU ! Bousteile! Louga OURO SOGUI AIRPORT o ! DODJI o Maghama Ould !( Kersani ! Yenje ! o 'Adel Bagrou Tanal o !o NIORO DU SAHEL SELIBABY YELIMANE ! NARA Niminiama! o! o ! Nioro 15°0'0"N Nara ! 15°0'0"N Selibabi Diadji ! DOUTENZA LEOPOLD SEDAR SENGHOR INTL Thies Touba Senegal Gouraye! du Sahel Sandigui (! Douentza Burkina (! !( o ! (!o !( Mbake Sandare!