Scandinavian Descendants of Charlemagne -253

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Erwin Panofsky

Reprinted from DE ARTIBUS OPUSCULA XL ESSAYS IN HONOR OF ERWIN PANOFSKY Edited l!J M I L LA RD M EIS S New York University Press • I90r Saint Bridget of Sweden As Represented in Illuminated Manuscripts CARL NORDENFALK When faced with the task of choosing an appropriate subject for a paper to be published in honor of Erwin Panofsky most contributors must have felt themselves confronted by an embarras de richesse. There are few main problems in the history of Western art, from the age of manuscripts to the age of movies, which have not received the benefit of Pan's learned, pointed, and playful pen. From this point of view, therefore, almost any subject would provide a suitable opportunity for building on foundations already laid by him to whom we all wish to pay homage. The task becomes at once more difficult if, in addition to this, more specific aims are to be considered. A Swede, for instance, wishing to see the art and culture of his own country play apart in this work, the association with which is itself an honor, would first of all have to ask himself if anything within his own national field of vision would have a meaning in this truly international context. From sight-seeing in the company of Erwin Panofsky during his memorable visit to Sweden in 1952 I recall some monuments and works of art in our country in which he took an enthusiastic interest and pleasure.' But considering them as illustrations for this volume, I have to realize that they are not of the international standard appropriate for such a concourse of contributors and readers from two continents. -

The Swedish Approach to Fairness

FACTS ABOUT SWEDEN | GENDER EQUALITY sweden.se PHOTO: MELKER DAHLSTRAND/IMAGEBANK.SWEDEN.SE PHOTO: The Swedish welfare system, which entitles both men and women to paid parental leave, has been central in promoting gender equality in Sweden. GENDER EQUALITY: THE SWEDISH APPROACH TO FAIRNESS Gender equality is one of the cornerstones of Swedish society. The aim of Sweden’s gender equality policies is to ensure that women and men enjoy the same opportunities, rights and obligations in all areas of life. The overarching principle is that every- areas of economics, politics, education school level onwards, with the aim of one, regardless of gender, has the right and health. Since the report’s inception, giving children the same opportunities to work and support themselves, to bal- Sweden has never finished lower than in life, regardless of their gender, by ance career and family life, and to live fourth in the Gender Gap rankings, which using teaching methods that counteract without the fear of abuse or violence. can be found at www.weforum.org. traditional gender patterns and gender Gender equality implies not only equal roles. distribution between men and women Gender equality at school Today, girls generally have better in all domains of society. It is also about Gender equality is strongly emphasised grades in Swedish schools than boys. the qualitative aspects, ensuring that in the Education Act, the law that gov- Girls also perform better in national the knowledge and experience of both erns all education in Sweden. It states tests, and a greater proportion of girls men and women are used to promote that gender equality should reach and complete upper secondary education. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

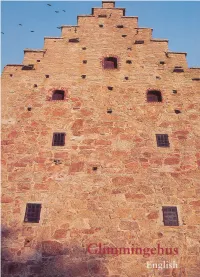

Digitalisering av redan tidigare utgivna vetenskapliga publikationer Dessa fotografier är offentliggjorda vilket innebär att vi använder oss av en undantagsregel i 23 och 49 a §§ lagen (1960:729) om upphovsrätt till litterära och konstnärliga verk (URL). Undantaget innebär att offentliggjorda fotografier får återges digitalt i anslutning till texten i en vetenskaplig framställning som inte framställs i förvärvssyfte. Undantaget gäller fotografier med både kända och okända upphovsmän. Bilderna märks med ©. Det är upp till var och en att beakta eventuella upphovsrätter. SWEDISH NATIONAL HERITAGE BOARD RIKSANTIKVARIEÄMBETET Cultural Monuments in S weden 7 Glimmingehus Anders Ödman National Heritage Board Back cover picture: Reconstruction of the Glimmingehus drawbridge with a narrow “night bridge” and a wide “day bridge”. The re construction is based on the timber details found when the drawbridge was discovered during the excavation of the moat. Drawing: Jan Antreski. Glimmingehus is No. 7 of a series entitled Svenska kulturminnen (“Cultural Monuments in Sweden”), a set of guides to some of the most interesting historic monuments in Sweden. A current list can be ordered from the National Heritage Board (Riksantikvarieämbetet) , Box 5405, SE- 114 84 Stockholm. Tel. 08-5191 8000. Author: Anders Ödman, curator of Lund University Historical Museum Translator: Alan Crozier Photographer: Rolf Salomonsson (colour), unless otherwise stated Drawings: Agneta Hildebrand, National Heritage Board, unless otherwise stated Editing and layout: Agneta Modig © Riksantikvarieämbetet 2000 1:1 ISBN 91-7209-183-5 Printer: Åbergs Tryckeri AB, Tomelilla 2000 View of the plain. Fortresses in Skåne In Skåne, or Scania as it is sometimes called circular ramparts which could hold large in English, there are roughly 150 sites with numbers of warriors, to protect the then a standing fortress or where legends and united Denmark against external enemies written sources say that there once was a and internal division. -

Appendix 1: Monastic and Religious Foundations in Thirteenth-Centur Y

APPENDIX 1: MONASTIC AND RELIGIOUS FOUNDATIONS IN THIRTEENTH-CENTURY FLANDERS AND HAINAUT Affiliation: Arrouaise Name Date of Foundation MenlWomen Eeckhout c. 1060/1146 Arrouaise Men Choques 1120/1138 Arrouaise Men Cysoing 855/1132 Arrouaise Men Phalernpin 1039/1145 Arrouaise Men Saint-Jean Baptiste c. 680/1142 Arrouaise Men Saint-Ni colas des Pres 1125/1140 Arrouaise Men Warneton 1066/1142 Arrouaise Men Zoetendale 1162/1215 re-founded Men Zonnebeke 1072/1142 Arrouaise Men Affiliation: Augustinian Canons Name Date of Foundation MenlWomen Saint-Aubert 963/1066 reforrned Men Saint-Marie, Voormezele 1069/1110 reforrned Men Saint-Martin, Ypres 1012/1102 reformed Men Saint-Pierre de Loo c. 1050/1093 reformed Men Saint-Pierre et Saint-Vaast c. 1091 Men Affiliation: Beguines Name Date cf Foundation MenlWomen Aardenburg 1249 Wornen Audenarde 1272 Wornen Bardonck, Y pres 1271/1273 Wornen Bergues 1259 Wornen 118 WOMEN, POWER, AND RELIGIOUS PATRONAGE Binehe 1248 Wornen Briel, Y pres 1240 Wornen Carnbrai 1233 Wornen Charnpfleury, Douai 1251 Wornen Damme 1259 Wornen Deinze 1273 Wornen Diksrnuide 1273 Wornen Ijzendijke 1276 Wornen Maubeuge 1273 Wornen Cantirnpre, Mons 1245 Wornen Orehies 1267 Wornen Portaaker (Ghent) 1273 Wornen Quesnoy 1246 Wornen Saint-Aubert (Bruges) 1270 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Courtrai) 1242 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Ghent) 1234 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Lilie) 1244/1245 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Valeneiennes) 1239 Wornen Ter Hooie (Ghent) 1262 Wornen Tournai 1241 Wornen Wetz (Douai) 1245 Wornen Wijngaard (Bruges) 1242 Wornen Affiliation: Benedictine Name Date oJ Foundation Men/Women Anehin 1079 Men Notre-Darne d'Avesnes 1028 Wornen Bergues Saint-Winoe 1028 Men Bourbourg c. 1099 Wornen Notre-Darne de Conde e. -

Helene Ingeborg Mortensdatter Hildre Mor Til Min Oldefar Nr. 8

Min tippoldemor Nr. 7; Helene Ingeborg Mortensdatter Hildre Mor til Min oldefar Nr. 8; Ole E. Røvreit Revidert 01.01.2020 1 Helen Ingeborg Mortensdatter Hildre f.11.07.1831 på Hildre og d.1916, 85 år gammel på Hildre. Gift med min tippoldefar Elias Andreas Rasmussen ( Hildre ) f.31.12.1836 og d.17.12. 1914. Helene Ingeborg var mor til min oldefar Ole E. Røvreit ( Nr. 8. Martinus Ole Elias Eliassen Hildre ). Helene Ingeborg var datter til Morten Andreas Ingebrigtsen f.1790 og d.05.09.1836, gift med Olave Olsdatter Hurlereiten f.1795 d.1881 fra Gnr. 23 Hurlen - Bnr. 7 Olagarden på Hurlen, Hildre. Bnr. 7 Olagarden er nabogarden til Gnr. 23 Hurlen – Bnr. 6 Røvreit hvor min mor kommer fra. Helene Ingeborg er som så mange av mine forfedre av de gamle ættene; «Store-Rasmus» Rasmus Myklebust, Tenfjord ætta, Haar ætta m.fl. Jeg vil her fortelle om Helene Ingeborgs ætt, og jeg har inndelt denne ættesoga i 2 deler; Del 1: Fra Tenfjord til Lille-Slyngstad Del 2: Fra Lille-Slyngstad til Hildre Gårder som er nevnt. Tenfjord – Slyngstad: Gnr. 72 Tenfjord Gnr. 77 Slyngstad Gnr. 78 Lille-Slyngstad Gnr. 73 Eidsvik Brattvåg – Årsundet: Gnr. 29 Årsund Hildre: Gnr. 24 Indre Hildre Gnr. 23 Hurlen 2 Haram kommune 3 Vatne og Slyngstad i Haram kommune 4 DEL 1: FRA TENFJORD TIL LILLE-SLYNGSTAD Om Gnr. 72 Tenfjord Tennfjord og Eidsvik «deler plassen» ved enden av Grytafjorden. Tenfjord ved den minste bukta i sør, og Eids- vik ved det nordøstlige hjørnet av fjordenden. Navnet Skrivemåten av gårdsnavnet veksler mye i de ulike kilder; Tænnafyrde ( AB ), Tennffiordh ( NRJ ), Tennefiord ( OE ), Tinfiord 1667, Tennfiord 1723, Tenfjord 1886. -

Towards the Kalmar Union

S P E C I A L I Z E D A G E N C I E S TOWARDS THE KALMAR UNION Dear Delegates, Welcome to the 31st Annual North American Model United Nations 2016 at the University of Toronto! On behalf of all of the staff at NAMUN, we welcome you to the Specialized Agency branch of the conference. I, and the rest of the committee staff are thrilled to have you be a delegate in Scandinavia during the High Middle Ages, taking on this challenging yet fascinating topic on the futures of the three Scandinavian Kingdoms in a time of despair, poverty, dependence and competitiveness. This will truly be a new committee experience, as you must really delve into the history of these Kingdoms and figure out how to cooperate with each other without sending everyone into their demise. To begin, in the Towards the Kalmar Union Specialized Agency, delegates will represent influential characters from Denmark, Norway and Sweden, which include prominent knights, monarchs, nobles, and important religious figures who dominate the political, military and economic scenes of their respective Kingdoms. The impending issues that will be discussed at the meeting in Kalmar, Sweden include the future of the Danish and Norwegian crowns after the death of the sole heir to the thrones, Olaf II. Here, two distant relatives to Valdemar IV have a claim to the throne and delegates will need to decide who will succeed to the throne. The second order of business is to discuss the growing German presence in Sweden, especially in major economic cities. -

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter Utgivna Av Statsvetenskapliga Föreningen I Uppsala 199

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter utgivna av Statsvetenskapliga föreningen i Uppsala 199 Secession och diplomati Unionsupplösningen 1905 speglad i korrespondens mellan UD, beskickningar och konsulat Redaktörer: Evert Vedung, Gustav Jakob Petersson och Tage Vedung 2017 © Statsvetenskapliga föreningen i Uppsala och redaktörerna 2017 Omslagslayout: Martin Högvall Omslagsbild: Tage Vedung, Evert Vedung ISSN 0346-7538 ISBN 978-91-513-0011-5 urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-326821 (http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-326821) Tryckt i Sverige av DanagårdLiTHO AB 2017 Till professor Stig Ekman Till minnet av docent Arne Wåhlstrand Inspiratörer och vägröjare Innehåll Förord ........................................................................................................ ix Secession och diplomati – en kronologi maj 1904 till december 1905 ...... 1 Secession och diplomati 1905 – en inledning .......................................... 29 Åtta bilder och åtta processer: digitalisering av diplomatpost från 1905 ... 49 A Utrikesdepartementet Stockholm – korrespondens med beskickningar och konsulat ............................................................. 77 B Beskickningar i Europa och USA ................................................... 163 Beskickningen i Berlin ...................................................................... 163 Beskickningen i Bryssel/Haag ......................................................... 197 Beskickningen i Konstantinopel ....................................................... 202 Beskickningen -

Wars Between the Danes and Germans, for the Possession Of

DD 491 •S68 K7 Copy 1 WARS BETWKEX THE DANES AND GERMANS. »OR TllR POSSESSION OF SCHLESWIG. BV t>K()F. ADOLPHUS L. KOEPPEN FROM THE "AMERICAN REVIEW" FOR NOVEMBER, U48. — ; WAKS BETWEEN THE DANES AND GERMANS, ^^^^ ' Ay o FOR THE POSSESSION OF SCHLESWIG. > XV / PART FIRST. li>t^^/ On feint d'ignorer que le Slesvig est une ancienne partie integTante de la Monarchie Danoise dont I'union indissoluble avec la couronne de Danemarc est consacree par les garanties solennelles des grandes Puissances de I'Eui'ope, et ou la langue et la nationalite Danoises existent depuis les temps les et entier, J)lus recules. On voudrait se cacher a soi-meme au monde qu'une grande partie de la popu- ation du Slesvig reste attacliee, avec une fidelite incbranlable, aux liens fondamentaux unissant le pays avec le Danemarc, et que cette population a constamment proteste de la maniere la plus ener- gique centre une incorporation dans la confederation Germanique, incorporation qu'on pretend medier moyennant une armee de ciuquante mille hommes ! Semi-official article. The political question with regard to the ic nation blind to the evidences of history, relations of the duchies of Schleswig and faith, and justice. Holstein to the kingdom of Denmark,which The Dano-Germanic contest is still at the present time has excited so great a going on : Denmark cannot yield ; she has movement in the North, and called the already lost so much that she cannot submit Scandinavian nations to arms in self-defence to any more losses for the future. The issue against Germanic aggression, is not one of a of this contest is of vital importance to her recent date. -

Estate Landscapes in Northern Europe: an Introduction

J Estate Landscapes in northern Europe an introduction By Jonathan Finch and Kristine Dyrmann This volume represents the first transnational exploration of the estate Harewood House, West Yorkshire, landscape in northern Europe. It brings together experts from six coun- UK Harewood House was built between tries to explore the character, role and significance of the estate over five /012 and /00/ for Edwin Lascelles, whose family made their fortune in the West hundred years during which the modern landscape took shape. They do Indies. The parkland was laid out over so from a variety of disciplinary backgrounds, to provide the first critical the same period by Lancelot ‘Capability’ study of the estate as a distinct cultural landscape. The northern European Brown and epitomizes the late-eighteenth countries discussed in this volume – Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, century taste for a more informal natural- the Netherlands and Britain – have a fascinating and deep shared history istic landscape. Small enclosed fields from of cultural, economic and social exchange and dialogue. Whilst not always the seventeenth century were replaced by a family at peace, they can lay claim to having forged many key aspects of parkland that could be grazed, just as it is the modern world, including commercial capitalism and industrialization today, although some hedgerow trees were retained to add interest within the park, from an overwhelmingly rural base in the early modern period. United such as those in the foreground. By the around the North Sea, the region was a gateway to the east through the early-nineteenth century all arable culti- Baltic Sea, and across the Atlantic to the New World in the west. -

The Swedish Club News

THE SWEDISH CLUB NEWS The Swedish Club of Houston Preserving Swedish Heritage on the Texas Gulf Coast Since 1986 Club Updates In the News ● Our Christmas Traditions program will ● Swedish tourist officials have started take place at Faith Lutheran Church in a new campaign, “Visit a Swede”. The Bellaire. The event will begin at 3 PM. initiative urges international travelers To volunteer, or sign up your kids for to meet up with a local Swede during the procession, please contact Marie their travels. More info: http://bit.ly/ Teahen at [email protected] VisitASwede ● Club member Evan Wood is this year’s ● Princess Madeleine has announced SCH Lucia. She has been interested her engagement to fiance Chris in all things Sweden for many years. O’Neil, a British-American Read more about her story on page 2. businessman. More info: http://bit.ly/ MadeleineEngagement ● Looking ahead: Our Pea Soup & Pancakes Annual Meeting is in ● Sofia Talvik, who played for us at January at Christ the King Lutheran the Crayfish party last March, is Church in Rice Village. The exact date continuing her US tour. Check out her is not set, so watch your email and video here: http://bit.ly/TalvikTravels swedishclub.org for updates. Nov/Dec 2012 - Page 1 Volume XXV No. 6 Our 2012 Lucia Evan Wood, daughter of Doug & Pam Wood, has been selected by the Board of Directors to be our 2012 Lucia! She is 17 years old, and is currently in her first year of college and holds a part time job at Campioni. She loves animals and flying airplanes. -

Suède Le Centre De Gravité De L'espace Scandinave

Suède Le centre de gravité de l'espace scandinave On s’est accoutumé, depuis le milieu du siècle dernier, à voir en la Suède un pays pacifique et un peu terne, une sorte de « Suisse du nord », vouée à professer depuis la tour d’ivoire de sa neutralité de tranquilles convictions sociales-démocrates. Bien loin d’être infâmante, cette image contient évidemment une part de vérité : appuyée sur une solide identité protestante, berceau de l’une des plus anciennes monarchies parlementaires au monde, préservée depuis 1815 des conflits qui ont affecté ses voisins, la Suède constitue incontestablement un des plus solides pivots de la démocratie et de la stabilité en Europe. Sans même parler de ce « modèle suédois », récemment mis à mal par les contrecoups de la mondialisation mais qui n’a peut-être pas dit son dernier mot… Cette apparence paisible ne doit pas faire oublier que la Suède a aussi et surtout été une grande et énergique puissance continentale, dont l’ambition a longtemps été d’unifier la Scandinavie, de contrôler les côtes de la mer Baltique et de jouer un rôle significatif dans les affaires de l’Allemagne et de la Russie. De ces rêves de grandeur et des quelques souverains exceptionnels qui les ont portés, il ne subsiste malheureusement pas grand-chose dans notre mémoire collective. En leurs temps, l’annonce de la mort de Gustave-Adolphe à la bataille de Lützen ou celle de Charles XII devant Fredriksten ont pourtant sonné comme autant de coups de tonnerre dans le ciel des capitales du vieux continent. -

Transnational Finnish Mobilities: Proceedings of Finnforum XI

Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen This volume is based on a selection of papers presented at Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) the conference FinnForum XI: Transnational Finnish Mobili- ties, held in Turku, Finland, in 2016. The twelve chapters dis- cuss two key issues of our time, mobility and transnational- ism, from the perspective of Finnish migration. The volume is divided into four sections. Part I, Mobile Pasts, Finland and Beyond, brings forth how Finland’s past – often imagined TRANSNATIONAL as more sedentary than today’s mobile world – was molded by various short and long-distance mobilities that occurred FINNISH MOBILITIES: both voluntarily and involuntarily. In Part II, Transnational Influences across the Atlantic, the focus is on sociocultural PROCEEDINGS OF transnationalism of Finnish migrants in the early 20th cen- tury United States. Taken together, Parts I and II show how FINNFORUM XI mobility and transnationalism are not unique features of our FINNISH MOBILITIES TRANSNATIONAL time, as scholars tend to portray them. Even before modern communication technologies and modes of transportation, migrants moved back and forth and nurtured transnational ties in various ways. Part III, Making of Contemporary Finn- ish America, examines how Finnishness is understood and maintained in North America today, focusing on the con- cepts of symbolic ethnicity and virtual villages. Part IV, Con- temporary Finnish Mobilities, centers on Finns’ present-day emigration patterns, repatriation experiences, and citizen- ship practices, illustrating how, globally speaking, Finns are privileged in their ability to be mobile and exercise transna- tionalism. Not only is the ability to move spread very uneven- ly, so is the capability to upkeep transnational connections, be they sociocultural, economic, political, or purely symbol- ic.