'I Who Speak Always Unpremeditately': the Earl of Mulgrave's Speeches Against Corruption and in Defence of His Honour, 16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Fifteenth Century Literary Culture with Particular

FIFTEENTH CENTURY LITERARY CULTURE WITH PARTICULAR* REFERENCE TO THE PATTERNS OF PATRONAGE, **FOCUSSING ON THE PATRONAGE OF THE STAFFORD FAMILY DURING THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY Elizabeth Ann Urquhart Submitted for the Degree of Ph.!)., September, 1985. Department of English Language, University of Sheffield. .1 ''CONTENTS page SUMMARY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ill INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 The Stafford Family 1066-1521 12 CHAPTER 2 How the Staffords could Afford Patronage 34 CHAPTER 3 The PrIce of Patronage 46 CHAPTER 4 The Staffords 1 Ownership of Books: (a) The Nature of the Evidence 56 (b) The Scope of the Survey 64 (c) Survey of the Staffords' Book Ownership, c. 1372-1521 66 (d) Survey of the Bourgchiers' Book Ownership, c. 1420-1523 209 CHAPTER 5 Considerations Arising from the Study of Stafford and Bourgchier Books 235 CHAPTER 6 A Brief Discussion of Book Ownership and Patronage Patterns amongst some of the Staffords' and Bourgchiers' Contemporaries 252 CONCLUSION A Piece in the Jigsaw 293 APPENDIX Duke Edward's Purchases of Printed Books and Manuscripts: Books Mentioned in some Surviving Accounts. 302 NOTES 306 TABLES 367 BIBLIOGRAPHY 379 FIFTEENTR CENTURY LITERARY CULTURE WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE PATTERNS OF PATRONAGE, FOCUSSING ON THE PATRONAGE OF THE STAFFORD FAMILY DURING THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY. Elizabeth Ann Urquhart. Submitted for the Degree of Ph.D., September, 1985. Department of English Language, University of Sheffield. SUMMARY The aim of this study is to investigate the nature of the r61e played by literary patronage in fostering fifteenth century English literature. The topic is approached by means of a detailed exam- ination of the books and patronage of the Stafford family. -

Robert De STAFFORD Born

Robert De STAFFORD Born: 1216, Stafford Castle, Staffordshire, England Died: 4 Jun 1261 / 1282 / AFT 15 Jul 1287Notes: summoned to serve in Wales in 1260. Cokayne's "Complete Peerage" (STAFFORD, p.171-172) Father: Henry De STAFFORD Mother: Pernell De FERRERS Married: Alice CORBET (dau. of Thomas De Corbet and Isabel De Valletort) ABT 1240, Shropshire, England Children: 1. Alice De STAFFORD 2. Nicholas De STAFFORD 3. Isabella De STAFFORD 4. Amabil De STAFFORD Alice De STAFFORD Born: ABT 1240, Stafford, England Father: Robert De STAFFORD Mother: Alice CORBET Married: John De HOTHAM (Sir) Children: 1. John De HOTHAM 2. Peter De HOTHAM Isabella De STAFFORD Born: 1265 Father: Robert De STAFFORD Mother: Alice CORBET Married: William STAFFORD Children: 1. John STAFFORD Amabil De STAFFORD Father: Robert De STAFFORD Mother: Alice CORBET Married: Richard (Robert) RADCLIFFE Nicholas De STAFFORD Born: 1246, Stafford, England Died: 1 Aug 1287, Siege of Droselan Castle Notes: actively engaged against the Welsh, in the reign of King Edward I, and was killed before Droselan Castle. His manors included Offley, Schelbedon and Bradley, Staffordshire Father: Robert De STAFFORD Mother: Alice CORBET Married 1: Anne De LANGLEY Married 2: Eleanor De CLINTON Children: 1. Richard De STAFFORD 2. Edmund STAFFORD (1º B. Stafford) Edmund STAFFORD (1º B. Stafford) Born: 15 Jul 1272/3, Clifton, Staffordshire, England Died: 26 Aug 1308 Father: Nicholas De STAFFORD Mother: Eleanor De CLINTON Married: Margaret BASSETT (B. Stafford) BEF 1298, Drayton, Staffordshire, England Children: 1. Ralph STAFFORD (1º E. Stafford) 2. Richard STAFFORD (Sir Knight) 3. Margaret STAFFORD 4. William STAFFORD 5. -

Shelburne Papers, Name and Geographical Index

William Petty, 1st Marquis of Lansdowne, William L. Clements Library 2nd Earl of Shelburne papers The University of Michigan Volume Index Finding Aid: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/clementsead/umich-wcl-M-66she?view=text Partial Name Index: Page 1 Geographical Subject Index: Page 14 Shelburne Partial Name Index Note: The following index does not include every name or contributor in the Shelburne Papers. Please see the card catalog for more details. "SFL" refers to volumes in the Shelburne family letters subseries and "LS" refers to the Lacaita-Shelburne series. Name: Volume Numbers Abbe’, Terray: 16 Almaine, G. C. d’: 152 Abercromby, James: 47 Alvensleben, Philip Karl, Baron: 136 Aberdeen, George Gordon, 3rd Earl: LS American Merchants: 67, 72 Aberdeen, George Hamilton Gordon, 4th Ancram, Earl of see also Kerr: 37 Earl: LS Anderson, James: 66 Abingdon, Willoughby Bertie, 4th Earl: Anglesey, Henry William Paget, LS Marquis of, 1768-1854: LS Adair, James, Recorder of London: 152 Anson, Lord George: 37, LS Adair, Sir Robert: LS Aranda, Le Comte d’: 71 Adams, John: 70 Arbuthnot, Charles: LS Adlam, John: 80 Archbishop of York: 59 Adolphys, John Leycester: LS Arcot, Nabob of: 92 Albemarle, Earl of (see William Charles Argyll, John Campbell, 5th Duke of: LS Keppel) Arnold, Benedict: 66, 67, 152, LS Aldborough, Edward Stratford, 2nd Earl: Arthur, Charles: 100 LS Ashburton, Alexander Baring, 1st Baron: Aldercon, John: 90 LS Ali Khan, Hyder: 91, 92, 93, 95, 98 Ashburton, John Dunning, 1st Baron: 98, Allan, John: 78: 165, LS Allen, Andrew: 88 Astle, -

Rewarding the Followers

What battle helped William become king? 1 Brain in Gear Name one reason William won this battle. 2 Quick 6! Match the date to the battle: Battle of Hastings 20th Sept 1066 th 3 Battle of Stamford Bridge 14 Oct 1066 Battle of Gate Fulford 25th Sept 1066 Why was William in a strong position after the earls submitted? 4 Why did Edward’s death have an impact on Anglo-Saxon England? 5 Describe two features of the military in Anglo-Saxon England. 6 What battle helped William become king? 1 Brain in Gear Name one reason William won this battle. 2 Quick 6! Match the date to the battle: Battle of Hastings 20th Sept 1066 th 3 Battle of Stamford Bridge 14 Oct 1066 Battle of Gate Fulford 25th Sept 1066 Why was William in a strong position after the earls submitted? 4 Why did Edward’s death have an impact on Anglo-Saxon England? 5 Describe two features of the military in Anglo-Saxon England. 6 Title: How did William reward his followers and establish control in the borderlands? Individual liberty, mutual respect Why is it and tolerance important to be a ‘gracious’ leader? Learning Objectives -Describe the key features of the Marcher Earldoms. -Explain why and how William rewarded his followers. -Assess the effectiveness of Marcher Earldoms. End1011121314151617181920123456789 Think End101112131415161718192021222324252627282930123456789 Pair End101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960123456789 Share Think, Pair, Share How could William, now King of England, get control of England? Who stands in his way? Do you think there are any problems he needs to deal with first and why? Establishing control on the borderlands Look at the map. -

Libeling Painting: Exploring the Gap Between Text and Image in the Critical Discourse on George Villiers, the First Duke of Buckingham

Libeling Painting: Exploring the Gap between Text and Image in the Critical Discourse on George Villiers, the First Duke of Buckingham THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ivana May Rosenblatt Graduate Program in History of Art The Ohio State University 2009 Master's Examination Committee: Barbara Haeger, Advisor Christian Kleinbub Copyright by Ivana May Rosenblatt 2009 Abstract This paper investigates the imagery of George Villiers, the first Duke of Buckingham, by reinserting it into the visual and material culture of the Stuart court and by considering the role that medium and style played in its interpretation. Recent scholarship on Buckingham‘s imagery has highlighted the oppositional figures in both Rubens‘ and Honthorst‘s allegorical paintings of the Duke, and, picking up on the existence of ―Felton Commended,‖ a libel which references these allegories in relation to illusion, argued dually that Buckingham‘s imagery is generally defensive, a result of his unstable position as royal favorite, and that these paintings consciously presented images of the Duke which explicitly and topically responded to verse libels criticizing him. However, in so doing, this scholarship ignores the gap between written libels and pictorial images and creates a direct dialogue between two media that did not speak directly to each other. In this thesis I strive to rectify these errors by examining a range of pictorial images of Buckingham, considering the different audiences of painting and verse libel and addressing the seventeenth-century understanding of the medium of painting, which defended painterly illusionism and positioned painting as a ritualized language. -

The Power of the Edge

The power of the edge Thomas Krijger The power of the edge The influence of the lords of the Welsh Marches on the political changes in England from 1258-1330 Thomas Krijger Master thesis – MA History 2 Contents Introduction 4 Chapter one: The meaning of the March 7 - The origins of the March 7 - Marcher Lords 8 - Parliament 11 Chapter two: Parliamentary revolution 13 - The Provisions of Oxford and the second barons’ war 14 - The role of the Marcher lords 18 - The disinherited 19 Chapter three: The King’s justice 23 - Edward, Llywelyn and the March 23 - The first war in Wales 25 - The war of conquest 26 - Quo warranto? 30 - Rights of the March 32 Chapter four: The tyranny of King Edward II 35 - Piers Gaveston 35 - Scotland and Bannockburn 37 - The rise of new favourites 38 - Hugh Despenser rules 41 - Isabella and Mortimer victorious 44 Conclusion 47 Bibliography 50 Appendix 55 Map of the March of Wales in the thirteenth century 59 3 Introduction The medieval border region of England and Wales was not a clearly defined one. It was unclear were England ended and Wales began, or as historian R. R. Davies put it: ‘Instead of a boundary, there was a March.’1 The March was home to a group of semi-autonomous lordships. These lordships were theoretically held by a lord in a feudal structure, and these lords had to do homage to the King of England for these lands. But the legal structures were different, as the Statutes of the realm proclaim: ‘In the marches, where the King’s writ does not run.’2 It is also mentioned in clause 56 of Magna Carta: ‘If we have deprived or dispossessed any Welshmen of lands, liberties, or anything else in England or in Wales, without the lawful judgement of their equals, these are at once to be returned to them. -

Titles – a Primer

Titles – A Primer The Society of Scottish Armigers, INC. Information Leaflet No. 21 Titles – A Primer The Peerage – There are five grades of the peerage: 1) Duke, 2) Marquess, 3) Earl, 4) Viscount and 5) Baron (England, GB, UK)/Lord of Parliament (Scotland). Over the centuries, certain customs and traditions have been established regarding styles and forms of address; they follow below: a. Duke & Duchess: Formal style: "The Most Noble the Duke of (title); although this is now very rare; the style is more usually, “His Grace the Duke of (Hamilton), and his address is, "Your Grace" or simply, "Duke” or “Duchess.” The eldest son uses one of his father's subsidiary titles as a courtesy. Younger sons use "Lord" followed by their first name (e.g., Lord David Scott); daughters are "Lady" followed by their first name (e.g., Lady Christina Hamilton); in conversation, they would be addressed as Lord David or Lady Christina. The same rules apply to eldest son's sons and daughters. The wife of a younger son uses”Lady” prior to her husbands name, (e.g. Lady David Scot) b. Marquess & Marchioness: Formal style: "The Most Honourable the Marquess/Marchioness (of) (title)" and address is "My Lord" or e.g., "Lord “Bute.” Other rules are the same as dukes. The eldest son, by courtesy, uses one of his father’s subsidiary titles. Wives of younger sons as for Dukes. c. Earl & Countess: Formal style: "The Right Honourable the Earl/Countess (of) (title)” and address style is the same as for a marquess. The eldest son uses one of his father's subsidiary titles as a courtesy. -

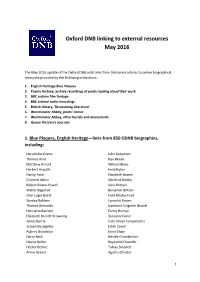

Oxford DNB Linking to External Resources May 2016

Oxford DNB linking to external resources May 2016 The May 2016 update of the Oxford DNB adds links from Dictionary articles to online biographical resources provided by the following institutions: 1. English Heritage Blue Plaques 2. Poetry Archive, archive recordings of poets reading aloud their work 3. BBC archive film footage 4. BBC archive radio recordings 5. British Library, ‘Discovering Literature’ 6. Westminster Abbey, poets’ corner 7. Westminster Abbey, other burials and monuments 8. Queen Victoria’s Journals 1. Blue Plaques, English Heritage—links from 850 ODNB biographies, including: Harold Abrahams John Betjeman Thomas Arne Nye Bevan Matthew Arnold William Blake Herbert Asquith Enid Blyton Nancy Astor Elizabeth Bowen Clement Attlee Winifred Holtby Robert Paden-Powell Vera Brittain Walter Bagehot Benjamin Britten John Logie Baird Ford Madox Ford Stanley Baldwin Lancelot Brown Thomas Barnardo Isambard Kingdom Brunel Henrietta Barnett Fanny Burney Elizabeth Barrett Browning Giovanni Canal James Barrie Cato Street Conspirators Joseph Bazalgette Edith Cavell Aubrey Beardsley Ernst Chain Harry Beck Neville Chamberlain Hilaire Belloc Raymond Chandler Hector Berlioz Tobias Smollett Annie Besant Agatha Christie 1 Winston Churchill Arthur Conan Doyle William Wilberforce John Constable Wells Coates Learie Constantine Wilkie Collins Noel Coward Ivy Compton-Burnett Thomas Daniel Charles Darwin Mohammed Jinnah Francisco de Miranda Amy Johnson Thomas de Quincey Celia Johnson Daniel Defoe Samuel Johnson Frederic Delius James Joyce Charles Dickens -

123 Robert D. Hume and Harold Love, Eds. Plays, Poems, And

REVIEWS 123 Robert D. Hume and Harold Love, eds. Plays, Poems, and Miscellaneous Writings associated with George Villiers, Second Duke of Buckingham. Including Sir Politick Would-be, Wallace Kirsop, ed., and H. Gaston Hall, trans. 2 vols. lxii + 770 pp. & xiii + 586 pp. £215. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. Cheryl Sawyer. The Winter Prince. New York and London: Signet Eclipse, New American Library, Penguin Group and Penguin Group Ltd., 2007. 384 pp. $14.00. Reviews by MAUREEN E. MULVIHILL PRINCETON RESEARCH FORU M , PRINCETON , NJ. In 2007, students of the seventeenth century welcomed two very different titles related to the highly-placed Villiers family: An ambitious two-volume collection of the writings, to date, “associated with,” though not necessarily “by,” George Villiers, second Duke of Buckingham (1628-1687), and a captivating historical novel on the reputed liaison between Buckingham’s intriguing older sister, Mary Vil- liers, later Stuart, Duchess of Richmond & Lennox (1622-1685), and Prince Rupert of the Rhine, that glamorous hero of the English Civil Wars and son of the unfortunate Elizabeth (Stuart) Electress Palatine, Bohemia’s ‘Winter Queen’. Both of these new offerings–one a sober scholarly venture, the other a creative reconstruction–engage with the literary culture of the Stuart court. We begin with that “blest madman,” as Dryden famously wrote of him in 1681: George Villiers. 124 SEVENTEENTH -CENTURY NEWS Image left: Hiding in Plain Sight. George Villiers, Second Duke of Bucking- ham (1628-1687), masquerading as Merry Andrew in the perilous streets of Crom- well’s London, circa 1649, and passing a packet of royalist communiqués, intermixed with anti-Villiers lampoons, to his sister Mary Villiers. -

The Precedence of the Earldom of Devon 1335-1485

Third Series Vol. VIII Part 2 ISSN 0010-003X No. 224 Price £12.00 Autumn 2012 THE COAT OF ARMS an heraldic journal published twice yearly by The Heraldry Society THE COAT OF ARMS The journal of the Heraldry Society Third series Volume VIII 2012 Part 2 Number 224 in the original series started in 1952 The Coat of Arms is published twice a year by The Heraldry Society, whose registered office is 53 Hitchin Street, Baldock, Hertfordshire SG7 6AQ. The Society was registered in England in 1956 as registered charity no. 241456. Founding Editor f John Brooke-Little, C.V.O., M.A., F.H.S. Honorary Editors C. E. A. Cheesman, M.A., PH.D, F.S.A., Richmond Herald M. P. D. O'Donoghue, M.A., York Herald Editorial Committee Adrian Ailes, M.A., D.PHIL., F.S.A., F.H.S. Jackson W. Armstrong, B.A., M.PHIL., PH.D. Noel Cox, LL.M., M.THEOL., PH.D, M.A., F.R.HIST.S. Andrew Hanham, B.A., PH.D, F.R.HIST.S. Advertizing Manager John Tunesi of Liongam www.the-coat-of-arms.co.uk THE PRECEDENCE OF THE EARLDOM OF DEVON 1335-1485 Michael Hicks Titles of honour distinguish those who possess them from those who do not. Dukes outrank marquesses who outrank earls, viscounts, barons and so on.1 Such titles en• able the holders to be ordered in processions, seating plans, and much else. Where individuals are of the same rank, however, precedence has to be established in other ways. The ceremonial context, which covered peers' ladies and even younger sons, was charted by G. -

160 the Fall of Suffolk and Normandy B Y 1445, William De La Pole, Duke

160 The Fall of Suffolk and Normandy B y 1445, William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk was clearly Henry's most trusted adviser. He faced a difficult task - to steer a bankrupt nation into the harbor of peace. Avoiding the ship of France trying to sink her on the way in. Would they make it? Formigny In this episode we are lucky enough to have another Weekly Word from Kevin Stroud, author of the History of English Podcast. If you like it, why not go the whole hog, and visit his website, The History of English Podcast. Also you might want to look at the rather touching letter from William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk to his eight year old son, John. - It's on the website. 161 Captain of Kent 1450 was an eventful year. The fall of Suffolk, and now Kent was once again in flames, just as it had been in 1381. This time the leader that emerged was one Jack Cade. Dramatis Personae This week, a few new names... William Aiscough, Bishop of Salisbury: only a cameo appearance for this episode. Jack Cade: Leader of the rebellion - again only a cameo appearance, leader of the rebellion of 1450. James Fiennes, Lord of Saye and Sele: Treasurer of England, and a nasty piece of work. He came to a sticky end! The Arms of Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham, 1402-1460 The Stafford family that are the holders of the title of the Duke of Buckingham, are of the blood royal; they are descended from Edward III’s youngest son, Thomas of Woodstock.