Three Kinds of Resumption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Clusters

Chapter 2 Feature Clusters 1. Introduction The goal of this Chapter is to address certain issues that pertain to the properties of feature clusters and the rules that govern their co-occurrences. Feature clusters come as fully specified (e.g. [+c+m] associated with people in (1a)) and ‘underspecified’ (e.g. [-c] associated with acquaintances in (1a)). Such partitioning of feature clusters raises the question of the implications of notions such as ‘underspecified’ and ‘fully specified’ in syntactic and semantic terms. The sharp contrast between the grammaticality of the middle derivation in (1b) and ungrammaticality of (1c) takes the investigation into rules that regulate the co-realization of feature clusters of the base-verb (1a). Another issue that is discussed in this Chapter is the status of arguments versus adjuncts in the Theta System. This topic is also of importance for tackling the issue of middles in Chapter 4 since – intriguingly enough – whereas (1c) is not an acceptable middle derivation in English, (1d) is. (1a) People[+c+m] don’t send expensive presents to acquaintances[-c] (1b) Expensive presents send easily. (1c) *Expensive presents send acquaintances easily. (1d) Expensive presents do not send easily to foreign countries. In section 2 of this Chapter, the properties of feature clusters with respect to syntax and semantics are examined. Section 3 sets the background for Section 4 by addressing the issue of conditions on thematic roles that have been assumed in the literature. Section 4 deals with conditions that govern the co-occurrences of feature clusters in the Theta System. The discussion in section 4 will necessitate the discussion of adjunct versus argument status of certain phrases. -

1 the Syntax of Scope Anna Szabolcsi January 1999 Submitted to Baltin—Collins, Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Theory

1 The Syntax of Scope Anna Szabolcsi January 1999 Submitted to Baltin—Collins, Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Theory 1. Introduction This chapter reviews some representative examples of scopal dependency and focuses on the issue of how the scope of quantifiers is determined. In particular, we will ask to what extent independently motivated syntactic considerations decide, delimit, or interact with scope interpretation. Many of the theories to be reviewed postulate a level of representation called Logical Form (LF). Originally, this level was invented for the purpose of determining quantifier scope. In current Minimalist theory, all output conditions (the theta-criterion, the case filter, subjacency, binding theory, etc.) are checked at LF. Thus, the study of LF is enormously broader than the study of the syntax of scope. The present chapter will not attempt to cover this broader topic. 1.1 Scope relations We are going to take the following definition as a point of departure: (1) The scope of an operator is the domain within which it has the ability to affect the interpretation of other expressions. Some uncontroversial examples of an operator having scope over an expression and affecting some aspect of its interpretation are as follows: Quantifier -- quantifier Quantifier -- pronoun Quantifier -- negative polarity item (NPI) Examples (2a,b) each have a reading on which every boy affects the interpretation of a planet by inducing referential variation: the planets can vary with the boys. In (2c), the teachers cannot vary with the boys. (2) a. Every boy named a planet. `for every boy, there is a possibly different planet that he named' b. -

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory Robert J. Kuhns Artificial Intelligence Center Arthur D. Little, Inc. Cambridge, MA 02140 USA Abstrae_~t For the purposes (and space limitations) of A parser which is founded on Chomskyts this paper we only briefly describe the theories Government-Binding Theory and implemented in of X-bar, Theta, Control, and Binding. We also PROLOG is described. By focussing on systems of will present three principles, viz., Theta- constraints as proposed by this theory, the Criterion, Projection Principle, and Binding system is capable of parsing without an Conditions. elaborate rule set and subcategorization features on lexical items. In addition to the 2.1 X-Bar Theory parse, theta, binding, and control relations are determined simultaneously. X-bar theory is one part of GB-theory which captures eross-categorial relations and 1. Introduction specifies the constraints on underlying structures. The two general schemata of X-bar A number of recent research efforts have theory are: explicitly grounded parser design on linguistic theory (e.g., Bayer et al. (1985), Berwick and Weinberg (1984), Marcus (1980), Reyle and Frey (1)a. X~Specifier (1983), and Wehrli (1983)). Although many of these parsers are based on generative grammar, b. X-------~X Complement and transformational grammar in particular, with few exceptions (Wehrli (1983)) the modular The types of categories that may precede or approach as suggested by this theory has been follow a head are similar and Specifier and lagging (Barton (1984)). Moreover, Chomsky Complement represent this commonality of the (1986) has recently suggested that rule-based pre-head and post-head categories, respectively. -

Principles and Parameters Set out from Europe

Principles and Parameters Set Out from Europe Mark Baker MIT Linguistics 50th Anniversary, 9 December 2011 1. The Opportunity Afforded (1980-1995) The conception of universal principles plus finite discrete parameters of variation offered: The hope and challenge of simultaneously doing justice to both the similarities and the differences among languages. The discovery and expectation of patterns in crosslinguistic variation. These were first presented with respect to “medium- sized” differences in European languages: The subjacency parameter (Rizzi, 1982) The pro-drop parameter (Chomsky, 1981; Kayne, 1984; Rizzi, 1982) They were then perhaps extended to the largest differences among languages around the world: The configurationality parameter(s) (Hale, 1983) “The more languages differ, the more they are the same” Example 1: Mohawk (Baker, 1988, 1991, 1996) Mohawk seems nonconfigurational, with no “syntactic” evidence of a VP containing the object and not the subject: (1) a. Sak wa-ha-hninu-’ ne ka-nakt-a’. Sak FACT-3mS-buy-PUNC NE 3n-bed-NSF b. Sak kanakta wahahninu’ c. Kanakta’ wahahninu’ ne Sak d. Kanakta’ Sak wahahninu’ e. Wahahninu’ ne Sak ne kanakta’ f. Wahahninu’ ne kanakta’ ne Sak g. Wahahninu’ ne kanakta’ h. Kanakta’ wahahninu’ i. Sak wahahninu’ j. Wahahninu’ ne Sak k. Wahahninu. All: ‘Sak/he bought a bed/it.’ There are also no differences between subject and object in binding (Condition C, neither c- commands the other) or wh-extraction (both are islands, no “subject condition”) (Baker 1992) Mohawk is polysynthetic (agreement, noun incorporation, applicative, causative, directionals…): (2) a. Sak wa-ha-nakt-a-hninu-’ Sak FACT-3mS-bed-Ø-buy-PUNC ‘Sak bought the bed.’ 1 b. -

I PREPOSITION STRANDING and PIED-PIPING in YORUBA FOCUS CONSTRUCTIONS by © Joseph Ajayi a Thesis Submitted to the School Of

PREPOSITION STRANDING AND PIED-PIPING IN YORUBA FOCUS CONSTRUCTIONS by © Joseph Ajayi A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Department of Linguistics Memorial University of Newfoundland July 2019 St John’s Newfoundland i ABSTRACT The thesis examines P-stranding and pied-piping in focus constructions in Yoruba language, one of the Benue-Congo languages spoken in Western part of Nigeria. This research is unique given the fact that while existing literature and theories on P-stranding and pied-piping have solely hammered cross- linguistic differences, the thesis discovers intra-linguistic features of P-stranding and pied-piping in Yoruba. According to literature, a language is either a P-stranding or pied-piping one. On the contrary, Yoruba exhibits both P-stranding and pied-piping features in similar environments in focus constructions. It is discovered that a number of prepositions can only strand while some others can solely pied-pipe. The thesis further examines another behavioral patterns of prepositions in Yoruba focus constructions. Interestingly and quite strangely, it is discovered that some prepositions drop, or pied-pipe with the occurrence of resumptive pronouns in Yoruba focus. These multifarious behavioral patterns of prepositions in Yoruba focus pose a great challenge as to how to account for these patterns within the existing literature and theories which rather deal with P-stranding as cross-linguistic affairs. The thesis, however, tackles this challenge by extracting two different theories to account for these preposition features in Yoruba focus as each of the theories (Abels 2003 Phase Theory and Law 1998 Incorporation Thoery) cannot, in isolation, capture the features. -

Minimal Pronouns1

1 Minimal Pronouns1 Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Bound Variable Pronouns Angelika Kratzer University of Massachusetts at Amherst June 2006 Abstract The paper challenges the widely accepted belief that the relation between a bound variable pronoun and its antecedent is not necessarily submitted to locality constraints. It argues that the locality constraints for bound variable pronouns that are not explicitly marked as such are often hard to detect because of (a) alternative strategies that produce the illusion of true bound variable interpretations and (b) language specific spell-out noise that obscures the presence of agreement chains. To identify and control for those interfering factors, the paper focuses on ‘fake indexicals’, 1st or 2nd person pronouns with bound variable interpretations. Following up on Kratzer (1998), I argue that (non-logophoric) fake indexicals are born with an incomplete set of features and acquire the remaining features via chains of local agreement relations established in the syntax. If fake indexicals are born with an incomplete set of features, we need a principled account of what those features are. The paper derives such an account from a semantic theory of pronominal features that is in line with contemporary typological work on possible pronominal paradigms. Keywords: agreement, bound variable pronouns, fake indexicals, meaning of pronominal features, pronominal ambiguity, typologogy of pronouns. 1 . I received much appreciated feedback from audiences in Paris (CSSP, September 2005), at UC Santa Cruz (November 2005), the University of Saarbrücken (workshop on DPs and QPs, December 2005), the University of Tokyo (SALT XIII, March 2006), and the University of Tromsø (workshop on decomposition, May 2006). -

Why and How to Distinguish Between Pro and Trace∗

Why and how to distinguish between pro ∗ and trace DALINA KALLULLI University of Vienna [email protected] Starting from a well-known observation, namely that in a language like Hebrew there is no free alternation between traces and (overt) resumptive pronouns, this paper aims to demonstrate that even in languages with seemingly little or no resumption such as English, the distinction between a putatively null resumptive pronoun and trace is equally material. More specifically, I contend that positing a resumptive (i.e. bound variable) pro also in English-like languages is not only theoretically appealing for various reasons (a.o. ideas in Hornstein 1999, 2001, Boeckx & Hornstein 2003, 2004, Kratzer 2009), but also empirically adequate (as conjectured e.g. in Cinque 1990). The central claim of this paper however is that resumption is restricted to (sometimes concealed) relatives. Applying this proposal to languages like English, the distinction drawn between (resumptive or bound variable) pro and trace accounts for phenomena as diverse as lack of superiority effects, lack of weak crossover in appositives, lack of Principle C effects in relative clauses, and so-called ATB movement phenomena. 1. Introduction Doron (1982) observed that in Hebrew, when a trace in a relative clause is c- commanded by a quantified expression, the sentence is ambiguous between a ‘single- individual’ and a ‘multiple-individual’ reading, as shown in (1), but if the trace position is filled by a resumptive pronoun, the multiple-individual interpretation is not available, as shown in (2). (1) ha-iSa Se kol gever hizmin hodeta lo the-woman Op every man invited thanked to-him a. -

RESUMPTIVE PRONOUNS in TUKI* 1. Introduction

Studies in African Linguistics Volume 21, Number 2, August 1990 RESUMPTIVE PRONOUNS IN TUKI* Edmond Biloa University of Southern California and University of Yaounde I, Cameroun This paper argues that in Tuki, gaps construed with WH- or topicalized phrases are null resumptive pronouns rather than WH-traces. Gaps alternate with overt resumptive pronouns. Structures with a gap parallel analogous structures with overt resumptive pronouns with regard to subjacency viola tions and violations of the Condition on Extraction Domains of Huang [1982], coordination tests, and weak crossover phenomena: gaps and overt pronominals fail to produce weak crossover violations, unlike structures with quantified NP's. Moreover, both the gaps and the overt resumptive pronouns license parasitic gaps, further strengthening the analogy. 1. Introduction This paper reveals that gaps in Tuki WH-constructions should be analyzed as null resumptive pronouns which do not involve movement rather than variables left * I am much indebted for providing helpful comments and reviewing drafts of this paper to Joseph Aoun, Carol Georgopoulos, Hajime Hoji, Osvaldo Jaeggli, Kenneth Safir, and Peter Sells. Thanks also go to Maria Luisa Zubizarreta with whom I have discussed in class material included here. Portions of this material were presented at the 20th Conference on African Linguistics at the University of Illinois. Thanks to the participants and to Joan Bresnan in particular for her encouragements. Errors are my responsibility. We have made use of the following symbols in the glosses: f1 = future tense one marker Neg = negation marker OM = object marker pI = past tense one marker p2 = past tense two marker SM = subject marker 212 Studies in African Linguistics 21 (2), 1990 by "Move Alpha". -

Resumptive and Bound Variable Pronouns in Tongan

UCLA Working Papers in Linguistics, no. 12, September 2005 Proceedings of AFLA XII, Heinz & Ntelitheos (eds.) RESUMPTIVE AND BOUND VARIABLE PRONOUNS IN TONGAN Randall Hendrick University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill [email protected] This paper describes the distribution of bound variable pronouns in Tongan and two classes of resump- tive pronouns that appear in the language (apparent and true resumptives). Bound variable pronouns and apparent resumptive pronouns are given a movement analysis, which is able to explain their com- mon behavior with respect to weak crossover and reconstruction effects. It also allows a derivational explanation for why they do not interact with true resumptive pronouns. 1. INTRODUCTION Pronouns are often viewed as shorthand expressions for their antecedents. This intuition stood behind the pronominalization transformations of the 1960s (cf. Stockwell et al. (1973)) in which a grammatical rule replaced the second occurrence of a DP with an appropriate pronoun. Sub- sequent work challenged this simple view of pronouns in two ways. Firstly, classes of structures were identified in which pronouns were not stylistic circumlocutions for a previously mentioned antecedent, and secondly, the hypothesized pronominalization transformation did not fit with well motivated constraints on movement transformations. Bound variable pronouns (pronouns that have quantified DPs as their antecedents) were taken to illustrate the first point (cf. Partee (1987)). The second point was illustrated by resumptive pronouns (pronouns that recapitulate an initial DP ei- ther in relative clauses or topicalized constructions), which are insensitive to island constraints that restricted wh-movement (e.g. Chomsky (1976)). In place of the transformational account, pronouns were taken to be lexical items inserted into syntactic structures like other lexical items. -

Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax 92 (2014) 1–32 ! 2

WORKING PAPERS IN SCANDINAVIAN SYNTAX 92 Elisabet Engdahl & Filippa Lindahl Preposed object pronouns in mainland Scandinavian 1–32 Katarina Lundin An unexpected gap with unexpected restrictions 33–57 Dennis Ott Controlling for movement: Reply to Wood (2012) 58–65 Halldór Ármann Sigur!sson About pronouns 65–98 June 2014 Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax ISSN: 1100-097x Johan Brandtler ed. Centre for Languages and Literature Box 201 S-221 00 Lund, Sweden Preface: Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax is an electronic publication for current articles relating to the study of Scandinavian syntax. The articles appearing herein are previously unpublished reports of ongoing research activities and may subsequently appear, revised or unrevised, in other publications. The WPSS homepage: http://project.sol.lu.se/grimm/working-papers-in-scandinavian-syntax/ The 93rd volume of WPSS will be published in December 2014. Papers intended for publication should be submitted no later than October 15, 2014. Contact: Johan Brandtler, editor [email protected]! Preposed object pronouns in mainland Scandinavian* Elisabet Engdahl & Filippa Lindahl University of Gothenburg Abstract We report on a study of preposed object pronouns using the Scandinavian Dialect Corpus. In other Germanic languages, e.g. Dutch and German, preposing of un- stressed object pronouns is restricted, compared with subject pronouns. In Danish, Norwegian and Swedish, we find several examples of preposed pronouns, ranging from completely unstressed to emphatically stressed pronouns. We have investi- gated the type of relation between the anaphoric pronoun and its antecedent and found that the most common pattern is rheme-topic chaining followed by topic- topic chaining and left dislocation with preposing. -

Handout 1: Basic Notions in Argument Structure

Handout 1: Basic Notions in Argument Structure Seminar The verb phrase and the syntax-semantics interface , Andrew McIntyre 1 Introduction 1.1 Some basic concepts Part of the knowledge we have about certain linguistic expressions is that they must or may appear with certain other expressions (their arguments ) in order to be interpreted semantically and in order to produce a syntactically well-formed phrase/sentence. (1) John put the book near the door put takes John, the book and near the door as arguments near takes the door and arguably the book as arguments (2) Fred’s reliance on Mary reliance takes on Mary and Fred as arguments (3) John is fond of his stamp collection fond takes his stamp collection and John as arguments An expression taking an argument is called a predicate in modern & philosophical terminology (distinguish from old terminology where predicate = verb phrase). An argument can itself be a predicate (4) Gertrude got angry (in some theories, angry is an argument of get , and Gertrude is an argument of both get and angry ) Some linguists say that arguments can be shared by two predicates, e.g. in (1) the book might be taken to be an argument of both put and near . Argument structure (valency) : the (study of) the arguments taken by expressions. In syntax, we say a predicate (e.g. a verb) has, takes, subcategorises for, selects this or that (or so-and-so many) argument(s). You cannot say you know a word unless you know its argument structure. A word’s argument structure must be mentioned in its lexical entry (=the information associated with the word in the mental lexicon , i.e. -

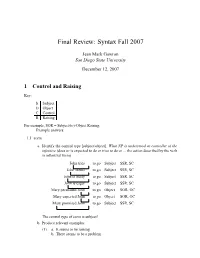

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007 Jean Mark Gawron San Diego State University December 12, 2007 1 Control and Raising Key: S Subject O Object C Control R Raising For example, SOR = Subject(to)-Object Raising. Example answers: 1.1 seem a. Identify the control type [subject/object]. What NP is understood as controller of the infinitive (does or is expected to do or tries to do or ... the action described by the verb in infinitival form) John tries to go Subject SSR, SC John seems to go Subject SSR, SC John is likely to go Subject SSR, SC John is eager to go Subject SSR, SC Mary persuaded John to go Object SOR, OC Mary expected John to go Object SOR, OC Mary promised John to go Subject SSR, SC The control type of seem is subject! b. Produce relevant examples: (1) a. Itseemstoberaining b. There seems to be a problem c. The chips seems to be down. d. It seems to be obvious that John is a fool. e. The police seem to have caught the burglar. f. The burglar seems to have been caught by the police. c. Example construction i. Construct embedded clause: (a) itrains. Simpleexample;dummysubject * John rains Testing dummy subjecthood ittorain Putintoinfinitivalform ii. Embed (a) ∆ seem [CP it to rain] Embed under seem [ctd.] it seem [CP t torain] Moveit— it seems [CP t to rain] Add tense, agreement (to main verb) d. Other examples (b) itisraining. Alternativeexample;dummysubject *Johnisraining Testingdummysubjecthood ittoberaining Putintoinfinitivalform ∆ seem [CP it to be raining] Embed under seem it seem [CP t toberaining] Moveit— it seems [CP t to be raining] Add tense, agreement (to main verb) (c) Thechipsaredown.