This Booklet Is for Members and Guests of Congregation Beth El

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jesus & the Jewish Wedding Ceremony Pt.2

Issue July-August 2018 / Av-Elul 5778 The Zion Letter The Monthly Newsletter of For Zion’s Sake Ministries, Inc. PO Box 1486 Bristol, TN 37620 www.forzionsake.org Phone: 276-644-1678 * Fax: 276-644-1689 * Email: [email protected] * Web: www.forzionsake.org Jesus & The Jewish Wedding Ceremony, Part 2 In last month's Zion Letter, we saw that Jesus followed the “Baruch Haba Bashem Adonai” (Blessed is He who pattern of the ancient Jewish wedding through the Erusin comes in the name of the Lord). (betrothal) stage. You may recall the words of Paul in 2Cor.11:2, "For I am jealous for you with a godly jeal- You may recall the word of Yeshua (Jesus) in Matthew ousy; for I betrothed you to one husband, that to Messiah I 23:37-39, when He said, "O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, who might present you as a pure virgin." Beloved, we are kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to her! How merely betrothed to Messiah in this life. Our wedding cer- often I wanted to gather your children together the way a emony and our bridegroom are yet to come! hen gathers her chicks under her wings and you were un- willing. Behold your house is being left to you desolate! For The ancient Jewish wedding ceremony had two parts: I say to you, from now on you shall not see Me until you Erusin (betrothal) and Nissuin (wedding). In Biblical say, ‘Blessed is He who comes in the name of the Lord’!” times, the two parts were held separately. -

Halachic and Hashkafic Issues in Contemporary Society 24 - Must a Kallah Cover Her Hair - Part 1 Ou Israel Center - Summer 2016

5776 - dbhbn ovrct [email protected] 1 sxc HALACHIC AND HASHKAFIC ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY 24 - MUST A KALLAH COVER HER HAIR - PART 1 OU ISRAEL CENTER - SUMMER 2016 A] HAIR COVERING FOR MARRIED WOMEN A1] THE TORAH DERIVATION - SOTAH //// v tv Jt«r , t g rpU wv hbpk v tv , t i v«F v sh ng vu 1. jh:v rcsnc The head of the sotah was made ‘paru’a’ in public. What does ‘parua’ mean? ivk htbd atrv hukda ktrah ,ubck itfn 'v,uzck hsf tvrga ,ghke ,t r,ux - grpu 2. oa h"ar Rashi explains the expression ‘para’ to refer to untying the woman’s braids and learns from this that Jewish women must cover their head. How does he get from one to the other? grpu (jh:v rcsnc) unf ubukeu umna vkd,b /vkudn - gurp :h"ar) /o vhneC vmnJk i º«r&vt v´«g rp(h F tU·v g*rp h¬F o ºgv(, t Æv J«n tr³Hu 3. (vatv atr ,t vf:ck ,una Rashi clearly learns that the word ‘parua’ means ‘uncovered’. utk t,ga tuvvs kkfn grpu ch,fsn b"t ruxts kkfn vkguc kg ,utb,vk v,aga unf vsn sdbf vsn vkuubk hfv vk ibhscgsn 4. rehg ifu atr ,ugurp ,tmk ktrah ,ubc lrs iht vbhn gna ,uv vgurp /cg ,ucu,f h"ar Rashi on the Gemara gives two derivations for the halacha: (a) uncovering the woman’s hair was designed to be a public humiliation and thus we can infer that covering the hair in public is dignified; and (b) the need to uncover the hair of the married woman implies that married women’s hair was generally covered. -

Yamim Noraim Flyer 12-Pg 5771

Days of Awe ………….. 5771 Rabbi Linda Holtzman • Rabbi Yael Levy Dina Schlossberg, President • Rabbit Brian Walt, Rabbi Emeritus Gabrielle Kaplan Mayer, Coordinator of Spiritual Life for Children & Youth Rivka Jarosh, Education Director 4101 Freeland Avenue • Philadelphia, PA 19128 Phone: 215-508-0226 • Fax: 215-508-0932 Email: [email protected] • Website: www.mishkan.org DAYS OF AWE 5771 Shalom, Welcome to a year of opportunity at Mishkan Shalom! Our first of many opportunities will be that of starting the year together at services for the Yamim Noraim. It is a pleasure to begin the year as a community, joining old friends and new, praying and learning together. This year, Rabbi Yael Levy will not be with us at the services for the Yamim Noraim. We will miss Rabbi Yael, and hope that her sabbatical time is fulfilling and energizing and that we will learn much from her when she returns to Mishkan Shalom in November. Our services will feel different this year, but the depth and talent of our many members who will participate will add real beauty to them. I am thrilled that joining us to lead the davening will be Sue Hoffman, Rabbi Rebecca Alpert, Cindy Shapiro, Karen Escovitz (Otter), Elliott batTzedek, Wendy Galson, Susan Windle, Andy Stone, Bill Grey, Dan Wolk, several of our teens and many other Mishkan members. As we look ahead to the new year, we pray that 5771 will be filled with abundant blessings for us and for the world. I look forward to celebrating with you. L’shalom, Rabbi Linda Holtzman SECTION 1: LOCATION , VOLUNTEER FORM , FEES AND SERVICE INFORMATION A: WE HAVE • Morning services on the first day of Rosh Hashanah and all services on Yom Kippur will be held at the Haverford School . -

Torah Vayikra: Leviticus 1:1 – 5:26 Haftarah: Isaiah 43:21 – 44:26 B’Rit Chadasha: Hebrews 10:1-23

Introduction to Parsha #24: Vayikra1 READINGS: Torah Vayikra: Leviticus 1:1 – 5:26 Haftarah: Isaiah 43:21 – 44:26 B’rit Chadasha: Hebrews 10:1-23 . and He [the Holy One] called/cried out . [Leviticus 1:1(a)] ___________________________________________________ This Week’s Amidah prayer Focus is the G’vurot, the Prayer of His Powers, Part II Vayikra el-Moshe – i.e. And He [the Holy One] called/cried out for Moshe . vayedaber Adonai elav me'Ohel Mo'ed – and the Holy One spoke to him from within the Tent of Meeting . Leviticus 1:1a. It has begun, Beloved! The glorious era of Imanu-El – i.e. God with us, dwelling in our midst, communing with us, and ruling over us – is underway! Behold, the Tabernacle of God will be with men, and He will be our God, and we will be His People2 . Selah! What Is that Strange and Wonderful Tent-Like Structure that Now Stands at the Epicenter of the Camp of B’nei Yisrael? How Will It Change our Lives? What Does it Portend For the World? The Immaculate Construction project called for by the Holy One’s Great Sinaitic ‘Mish’kan Discourse’3 is now complete. The 'Tabernacle' - the structure that the Hebrew text of Torah calls not only the ‘Mish’kan’ (abode/dwelling place), but also the Mik’dash (receptacle/repository of flowing, pulsing holiness), and the Ohel Moed (Tent of Meeting/Communion/Appointment) - is in place. The moveable, shadow-box edifice the Holy One told Moshe He wanted us to build 1 All rights with respect to this publication are reserved to the author, William G. -

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

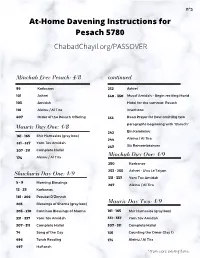

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

Rosh Hashanah Ubhct Ubfkn

vbav atrk vkp, Rosh HaShanah ubhct ubfkn /UbkIe g©n§J 'UbFk©n Ubhc¨t Avinu Malkeinu, hear our voice. /W¤Ng k¥t¨r§G°h i¤r¤eo¥r¨v 'UbFk©n Ubhc¨t Avinu Malkeinu, give strength to your people Israel. /ohcIy ohH° jr© px¥CUb c,§ F 'UbFknUbh© ct¨ Avinu Malkeinu, inscribe us for blessing in the Book of Life. /vcIy v²b¨J Ubhkg J¥S©j 'UbFk©n Ubhc¨t Avinu Malkeinu, let the new year be a good year for us. 1 In the seventh month, hghc§J©v J¤s«jC on the first day of the month, J¤s«jk s¨j¤tC there shall be a sacred assembly, iIº,C©J ofk v®h§v°h a cessation from work, vgUr§T iIrf°z a day of commemoration /J¤s«et¨r§e¦n proclaimed by the sound v¨s«cg ,ftk§nkF of the Shofar. /U·Gg©, tO Lev. 23:24-25 Ub¨J§S¦e r¤J£t 'ok«ug¨v Qk¤n Ubh¥vO¡t '²h±h v¨T©t QUrC /c«uy o«uh (lWez¨AW) k¤J r¯b ehk§s©vk Ub²um±uuh¨,«um¦nC Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu melech ha-olam, asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu l’hadlik ner shel (Shabbat v’shel) Yom Tov. We praise You, Eternal God, Sovereign of the universe, who hallows us with mitzvot and commands us to kindle the lights of (Shabbat and) Yom Tov. 'ok«ug¨v Qk¤n Ubh¥vO¡t '²h±h v¨T©t QUrC /v®Z©v i©n±Zk Ubgh°D¦v±u Ub¨n±H¦e±u Ub²h¡j¤v¤J Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu melech ha-olam, shehecheyanu v’kiy’manu v’higiyanu, lazman hazeh. -

Ruach Congregation Beth Shalom

6800 35th Ave NE Ruach Seattle, WA 98115 Congregation Beth Shalom 206.524.0075 September 2017 • Elul 5777-Tishrei 5778 Volume 50, Issue 1 MESSAGE FROM RABBI BORODIN A Yom Kippur Challenge Amram Gaon, then 22 with Maimonides in the 12th century, to 36 sins in the Machzor Vitry (only slightly later than Judaism is based on a few foundational principles. One of Maimonides), to our 44 line version found in our machzorim these is that there is a difference between right and wrong, today. Its current form is an acrostic, hoping to suggest the and we as humans can learn and discern between them. A extensive breadth in which we have sinned and erred, both second principle is that, as human beings, we are both through omission and commission. This formula is intended imperfect and we can improve and make some correction for to inspire us and assist us on the process of self-reflection past errors. And a third is about the importance of regularly and confession. It is not supposed to be a substitute of our examining our character and admitting our wrongs as part own process and directly asking for forgiveness from the of a program of self-improvement. people we have hurt. This self-reflection exercise is intended to be daily with a I find reciting the al chet prayer powerful - perhaps because more in depth examination connected to the high holidays, of the physical aspect of beating our hearts, and through our and Yom Kippur in particular. To help with this process, communal singing of part of it. -

A Guide to Our Shabbat Morning Service

Torah Crown – Kiev – 1809 Courtesy of Temple Beth Sholom Judaica Museum Rabbi Alan B. Lucas Assistant Rabbi Cantor Cecelia Beyer Ofer S. Barnoy Ritual Director Executive Director Rabbi Sidney Solomon Donna Bartolomeo Director of Lifelong Learning Religious School Director Gila Hadani Ward Sharon Solomon Early Childhood Center Camp Director Dir.Helayne Cohen Ginger Bloom a guide to our Endowment Director Museum Curator Bernice Cohen Bat Sheva Slavin shabbat morning service 401 Roslyn Road Roslyn Heights, NY 11577 Phone 516-621-2288 FAX 516- 621- 0417 e-mail – [email protected] www.tbsroslyn.org a member of united synagogue of conservative judaism ברוכים הבאים Welcome welcome to Temple Beth Sholom and our Shabbat And they came, every morning services. The purpose of this pamphlet is to provide those one whose heart was who are not acquainted with our synagogue or with our services with a brief introduction to both. Included in this booklet are a history stirred, and every one of Temple Beth Sholom, a description of the art and symbols in whose spirit was will- our sanctuary, and an explanation of the different sections of our ing; and they brought Saturday morning service. an offering to Adonai. We hope this booklet helps you feel more comfortable during our service, enables you to have a better understanding of the service, and introduces you to the joy of communal worship. While this booklet Exodus 35:21 will attempt to answer some of the most frequently asked questions about the synagogue and service, it cannot possibly anticipate all your questions. Please do not hesitate to approach our clergy or regular worshipers with your questions following our services. -

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim Cantor Sherwood Goffin Faculty, Belz School of Jewish Music, RIETS, Yeshiva University Cantor, Lincoln Square Synagogue, New York City Song has been the paradigm of Jewish Prayer from time immemorial. The Talmud Brochos 26a, states that “Tefillot kneged tmidim tiknum”, that “prayer was established in place of the sacrifices”. The Mishnah Tamid 7:3 relates that most of the sacrifices, with few exceptions, were accompanied by the music and song of the Leviim.11 It is therefore clear that our custom for the past two millennia was that just as the korbanot of Temple times were conducted with song, tefillah was also conducted with song. This is true in our own day as well. Today this song is expressed with the musical nusach only or, as is the prevalent custom, nusach interspersed with inspiring communally-sung niggunim. It once was true that if you wanted to daven in a shul that sang together, you had to go to your local Young Israel, the movement that first instituted congregational melodies c. 1910-15. Most of the Orthodox congregations of those days – until the late 1960s and mid-70s - eschewed the concept of congregational melodies. In the contemporary synagogue of today, however, the experience of the entire congregation singing an inspiring melody together is standard and expected. Are there guidelines for the proper choice and use of “known” niggunim at various places in the tefillot of the Yamim Noraim? Many are aware that there are specific tefillot that must be sung "...b'niggunim hanehugim......b'niggun yodua um'sukon um'kubal b'chol t'futzos ho'oretz...mimei kedem." – "...with the traditional melodies...the melody that is known, correct and accepted 11 In Arachin 11a there is a dispute as to whether song is m’akeiv a korban, and includes 10 biblical sources for song that is required to accompany the korbanos. -

Answers Disguised As Questions: Rhetoric and Reasoning in Psalm 24

Botha: Rhetoric and Reasoning in Psalm 24 OTE 22/3 (2009), 535-553 535 Answers Disguised as Questions: Rhetoric and Reasoning in Psalm 24 PHIL J. BOTHA (U NIVERSITY OF PRETORIA ) ABSTRACT Psalm 24 seems to consist mainly of a hymnic introduction (vv. 1-2), a so-called “entrance torah” (vv. 3-5), and a liturgical piece once used at the temple gates (vv. 7-10), to which a post-exilic identifica- tion of the true Israel was added (v. 6). It contains four questions which are almost universally interpreted as dialectical or antipho- nal questions formulated for the purpose of regulating entrance to the temple within some or other liturgy. This paper consists of a po- etic and rhetorical analysis of the psalm in which it is argued that the questions rather serve a rhetorical function in the present form of Ps 24. The purpose of the questions is to highlight the profile of a true worshipper of YHWH on the one hand, and to highlight the military might and splendour of YHWH on the other. It probably sought to outline the religious profile of the worshipping community in the post-exilic period more clearly, and to reconfirm the consen- sus that they would be vindicated as the true Israel when YHWH would reveal his true power and glory. The psalm is also contextu- alised as part of the post-exilic composition Pss 15-24. A INTRODUCTION It is widely accepted that Ps 24 contains remnants of two liturgical pieces: A so-called “entrance torah” (vv. 3-5, with parallels in Ps 15 and Isa 33), 1 and a so-called “liturgy at the gates” (vv. -

Midway Jewish Center Bar and Bat Mitzvah Guide Page 2

LET’S START PLANNING A—BAR/T MITZVAH BAT & BAR MITZVAH THE ULTIMATE MJC GUIDE FOR BAR/BAT MITZVAH Perry Raphael Rank Rabbi Joel Levenson Associate Rabbi Lisa Stein Director of Education Sandi Bettan Preschool Director Genea Moore Synagogue Administrator Michael Kohler President Howard Rosen Ritual Committee Chair Office Phone (516) 938-8390 Office Fax (516) 938-3906 E-Mail [email protected] Revised December, 2016 / Kislev, 5777 Midway Jewish Center Bar and Bat Mitzvah Guide Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 WHAT IS BAR/T MITZVAH? 3 HOW MUCH OF THE SERVICE OUR CHILDREN WILL KNOW 4 WHY WE TEACH WHAT WE TEACH 4 RABBIS' ROLES 5 THE TUTORS' ROLES 5 TIMETABLE FOR THE BAR/T MITZVAH EXPERIENCE 7 HELPING OUR CHILDREN BECOME RESPONSIBLE JEWS 7 EDUCATIONAL AND RELIGIOUS REQUIREMENTS 8 THE DIRECTIONS / DECORUM CARD 9 BAR/T MITZVAH INVITATION DISPLAY POLICY 9 HONORS 10 KIDDUSH 10 SE'UDAH SHEL MITZVAH—A MEAL EMANATING FROM A MITZVAH 10 SYNAGOGUE DECORUM 10 A TZEDAKKAH OPPORTUNITY 11 SOME TERMS YOU OUGHT TO KNOW 12 AN ALIYAH: IT’S AN HONOR -- BUT WHAT DO I DO? 18 Midway Jewish Center Bar and Bat Mitzvah Guide Page 3 INTRODUCTION Is it hard to believe that your child will soon become a Bar or Bat Mitzvah? You might as well brace yourself now. That little boy or girl that just yesterday was strapped into a car seat is today getting all set for adolescence. Our children begin to go through some dramatic changes, physically and emotionally, at the age of thirteen. The rabbis were wise in choosing this age as the proper time for becoming Bar/t Mitzvah. -

History of Jewish Liturgy Schiffman

Kol Hamevaser Halakhah and Minhag History and Liturgy: The Evolution of Multiple Prayer Rites BY: Dr. Lawrence H. Schiffman (or nineteen) benedictions of the Amidah , and pire, Greece and European Turkey until the 16 th in the newly-emerging Sephardic and Ashke - the closing of the last Amidah blessing with century or perhaps later, when it was pushed nazic communities. For reasons that are not he family tree of Jewish liturgy – the “oseh ha-shalom ” (He Who makes peace) in out by the Sephardic rite as a result of immi - totally clear, the version of Rav Sa’adyah typ - siddur and the mahazor (as it is cor - place of “ ha-mevarekh et ammo Yisrael ba- gration of expelled Sephardim and of the later ifies the Babylonian liturgy as it was exported Trectly vocalized) – is a long and com - shalom ” (He Who blesses His nation Israel Kabbalistic and halakhic influences of the with other Babylonian halakhic traditions to plex one. It spans the entire history of the with peace). A further important feature was Shulhan Arukh . This rite, like the Sephardic, the emerging Jewish communities of the Iber - Jewish experience, from the earliest origins of the role of Byzantine period piyyut . Poetry places the Hodu section before Barukh she- ian Peninsula. the Jewish people to the present day. The story was a prominent part of the liturgy of the Sec - Amar , inserts “ ve-yatsmah purkaneih vi- The so-called Babylonian rite is reflected of the many Jewish prayer rites ( nusha’ot ) is ond Temple period, as is evidenced in sectarian yekarev meshiheih u-parek ammeih in the Sephardic prayer book, originally of the in fact the story of the diffusion of the Jewish texts and fragments preserved in Tannaitic lit - be-rahmateih le-dor va-dor ” (may He cause Iberian Peninsula, which, after the expulsion people and their tradition throughout the world erature.